How Britain's Medieval Playbook for Industrialization affects Trade Today

Not Adam Smith but Daniel Defoe

Let’s look at a map of 1700s Europe:

Back then, there was no united Germany or Italy, Belgium didn’t exist (it was part of Netherlands), and Ottoman Turkey controlled Greece, Moldova, and Albania. The map of Europe back then is different from today.

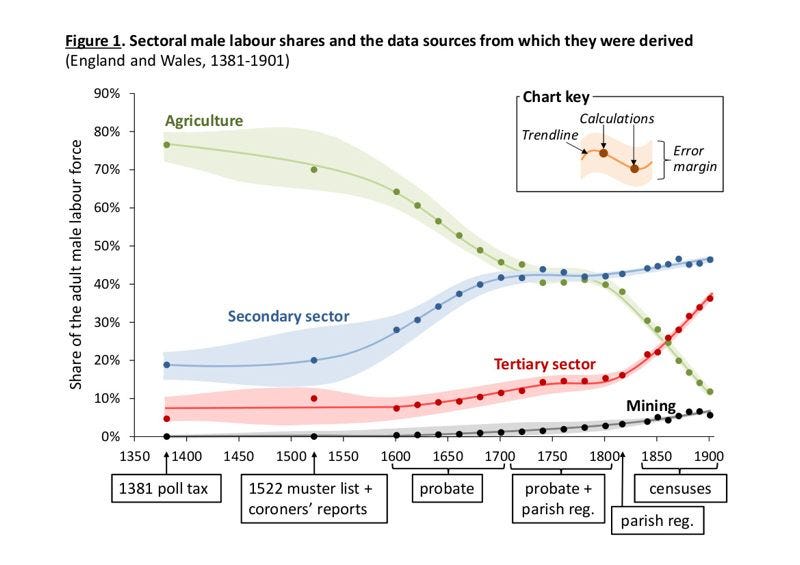

Britain, the first country to industrialize and use that power to take over the world, had manufacturing employment overtake farming jobs in the mid 1700s. See graph below:

As you can see, the “secondary sector”, which is manufacturing and production jobs, exploded in the late 1500s/early 1600s, and overtook agriculture by the 1750s. In addition, agricultural employment sharply dropped. Why did this happen?

Some people would argue is that Britain industrialized because of colonialism. However, I think that’s putting the “cart before the horse”, because the next question a sensible person would ask is why did Britain have the ability to colonize the world in the first place. It must have had the power & economy internally first before it can go out and conquer. That’s where industrialization comes in.

Firstly, Britain had an agricultural revolution first, which pushed up agricultural yields. The second part is how the British industrialized.

In short - the government developed a really good strategy to help the private sector.

An Economist named Daniel Defoe wrote a book “A Plan for the English Commerce” in 1728. Defoe discussed how the monarchs of England contributed to England’s greatness.

Defoe describes how the Tudor Monarchs - Elizabeth I and Henry VII (we are talking 1450s-1600s here) did the following:

1. High tariffs on imported textile products

2. Subsidies for English textile manufactures

3. High export taxes & outright export bans on raw wool

4. Granting monopoly rights to certain firms

5. Outright Theft Government sponsored industrial espionage on the Dutch

And a butch of other measures to establish England as the textile manufacturing powerhouse of the world in the 1700s. (Back then textile manufacturing in the middle ages was like AI in the 2020s). Does any of this sound familiar?

Quite frankly, America, Germany, France, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and now modern-day China have gotten richer that same manner. We call this import substitution industrialization(ISI). Then after the industries are created, you focus on exports to make your businesses more productive -export-led industrialization (ELI). (In America’s case because it had a massive domestic market, export led growth wasn’t as necessary for America).

Exports do the following:

1. Increase Economies of scale. Exporting enables firms to expand their production volumes, which in turn allows them to distribute fixed costs across a larger output. By producing more goods, a factory can reduce the average cost per unit, thereby enhancing efficiency. For instance, if a textile firm in England exports 10,000 shirts to all of Europe, the cost per shirt becomes lower compared to selling just 1,000 shirts domestically. Additionally, scaling up production facilitates bulk purchasing, enabling firms to negotiate better prices for raw materials like cotton. Higher demand for the products also leads to increased sales, providing firms with greater revenue to invest in advanced machinery and equipment without resorting to borrowing and risking bankruptcy.

2. Access to larger markets. British firms were focused on selling to all markets in Europe. Not just England.

3. Learning and innovation. If British firms are competing with the Dutch firms in the Dutch market, Britain has to innovate to make Dutch people buy British goods.

However, this is a high risk - high reward strategy. Sometimes the government isn’t great at picking winner industries & winner companies. This worked great for Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, & post 1980s China, has had some success in Brazilian Aerospace—Embraer, and has had terrible results, wrought with mismanagement in many other countries (Ghanaian shipbuilding, Congolese spacecraft, Algerian cars, Nigerian textiles, I could go on)... To be fair, Britain was the 1st industrialized country, so they didn’t face any industrialized competition, and Britain employed this strategy over centuries until the mid 1800s. That’s a luxury the developing world doesn’t have.

Until the Tudor monarchs, Britain, was relatively backwards. It borrowed and spent gold to import silk and clothes from the Netherlands, the proto-industrial power of that time. England exported raw wool. The Dutch & Flemish enterprises took wool and made clothes to make greater profits.

Now any country that wants to get richer has to move up the value chain. Britain would not have been the superpower if it stayed as an island that sold raw wool. Countries become richer by having businesses make more complex items that other countries can’t make and then rake in high profits - competitive advantage through differentiation.

Henry VII sent royal missions to identify locations in England suitable for woolen manufacturing. He, and his predecessor Edward III, would pay Dutch workers to come work in England. He imposed export taxes on raw wool sellers, and even he even banned selling raw wool to encourage processing of raw wool in England. In 1489, England banned the sale of unfinished cloth (except for a few types of unfinished cloth that Europeans would buy at high value). By the 1500s, England banned the sale of unfinished cloth.

It took a century for England to catch up to Dutch, and then by the late 1500s, Henri VII had enough processing capacity to ban raw wool exports entirely. Without raw wool that the Dutch could import, they couldn’t make textiles anymore, driving some Dutch textile firms to bankruptcy. The Dutch had to spend capital looking for new places to get raw wool… Like the East Indies(Indonesia)… or Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

Without Dutch competition, England became the premier place for textile manufacturing. By 1600s, England had transformed from a raw wool exporter to a textile manufacturer. Now England earned foreign exchange (gold and silver) to pay for the raw materials and food imports selling “high-end” clothes.

In the Middle Ages, England didn’t develop through “Free market capitalism” but rather through mercantilist capitalism. Then Britain got its first colony in Jamestown, Virginia in 1607. Strength came first, colonialism second.

If the English government did not intervene, market signals would simply make English firms focus on their comparative advantage and sell only raw wool. This is an example of the government defying market signals to protect their infant industries, steal from the Dutch, and subsidize it to make England a textile King.

Conclusion

The idea of import substitution industrialization (ISI) is that if your industry is not developed yet, you need to protect your businesses from foreign competition until they can compete. If your fledging industry competes with big players right away they’ll be crushed.

Asking fledgling industries to compete on global markets immediately is like letting your five year old child to immediately drudge his life away in a factory, instead of allowing him to be educated for 22 years so he can get a good job as a software engineer. Your kid could work screwing wrenches, but I am fairly certain that you when your 5 year old kid is 22 years old, he’ll still be making less in lifetime earnings than a person with 22 years of education working as a Software engineer at Apple. Educating your kid is analogous to the government protecting infant industries.

However like anything, you could give too much of a good thing. Too much protection can turn your infant industries into fat infants, and paying your kid to have a useless degree could make your kid ill prepared for the workforce. Getting the balance between protection and exposure is something that countries like Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and China got right and where most of Africa, Latin America, and South Asia are still struggling with.

Then, once you have developed that industry, you can focus on Export-oriented Industrialization (EOI). You reward your firms for exporting. This is what has helped the West, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, and now China.

The Western world is now relearning the lessons that free trade may damage some important industries and companies, if they don’t already have an overwhelming advantage. Now that China is catching up with the West, America is applying a 100% tariff on Chinese Electric Vehicles to protect Tesla, and the European Union is applying non-tariff, regulatory barriers (national security, labor standards, environmental restrictions) to protect Volkswagen, Audi, and BMW EVs/Hybrids. South Korea is also thinking of using environmental regulation to protect Hyundai from Chinese cars. We are now entering a new age where the West is abandoning Adam Smith and relearning Daniel Defoe.

Links are Attached!

Great essay. The origins of the English textiles industry are quite interesting and historically relevant.

One additional point that could be made is that the impact of government policy on the English textile industry goes much further back than Defoe. The industry went through 4 phases. Each was heavily influenced by government policy:

1 Raw wool exports

2 Wool cloth exports (so-called Old Draperies)

3 New Draperies

4 Cotton textile exports

In the 13th and 14th Century raw wool made up 90% of England’s export revenues. In 1275 the Crown started taxing raw wool exports for the first time. The Crown kept increasing the taxes to pay for the constant wars with France. It was not industrial policy, only a means to raise revenue. This tax encouraged the English to shift from raw wool to processing the raw wool into woolen cloth.

Then in 1363 the Calais Staple Company, a government-sponsored import monopoly in Calais, was established to shift taxes to the Low Countries. By the 1390s the taxes were 50% of the price of wool exports. Due to the taxes, the Flemish switched from English raw wool to Spanish merino wool as a supplier.

From 1465-1550s England dominated the European wool cloth industry (based mainly on exports to Antwerp).

A similar change happened with New Draperies, a lighter, cheaper and less durable type of woolen cloth), and later cotton textiles. The Calico Act of 1721 forbade importation and wearing of Indian textiles, helping the fledgling British cotton textile industry.

Isn't part of the problem with ISI that the locals are too poor to afford cars or textile in the first place. I guess you can adopt different paths for different sectors at the same time.

For example, in Bangladesh we give export incentives to textiles and ICT. But we do import substitution for cars and consumer electronics. Personally, I'm more moderate on industrial policy. But I'm fine with "protecting" the car industry because less than 10% of Bangladeshis own cars and crude oil is our biggest import. Worst case scenario, it's basically a luxury tax. I think Ethiopia banned ICE passenger vehicles because fuel is also a big import item. Plus 30% of our taxes comes from tariffs despite being the lowest taxed country in the world. So we can't exactly afford to stop imposing tariffs.