The Economic & Geopolitical History of Uganda Part I: Pre-Colonial & Colonial Times

Imagine Britain establishing a colony through a regional Imperialist—that's how Uganda was created

Uganda, a landlocked East African country with a population of 50 million (as of September 2024), is roughly the size of the UK or Oregon. Its capital, Kampala, and the country itself, is home to a diverse, primarily Christian, population, with major tribes including the Baganda, Banyankole, Banyarwanda, Lango, Acholi, and more. English, Luganda, and Swahili are widely spoken. The country’s name comes from a mispronunciation of the traditional Buganda Kingdom, but Swahili Afro-Arab traders and later the British dropped the “B.”

Uganda’s landlocked status raises its freight costs by 50% compared to if it was a coastal country, making the country reliant on Kenya and Tanzania for trade. Political unrest in Kenya, like railway disruptions during protests for example, directly impacts Uganda’s economy.

Uganda's Human Development Index (HDI) stands at 55%, higher than neighbors like South Sudan (38%), Tanzania (53%), Rwanda (54.8%), and the Democratic Republic of Congo (48%), but behind Kenya (60%). The Central region, including the capital and the historic Buganda Kingdom, is the most developed part of the country.

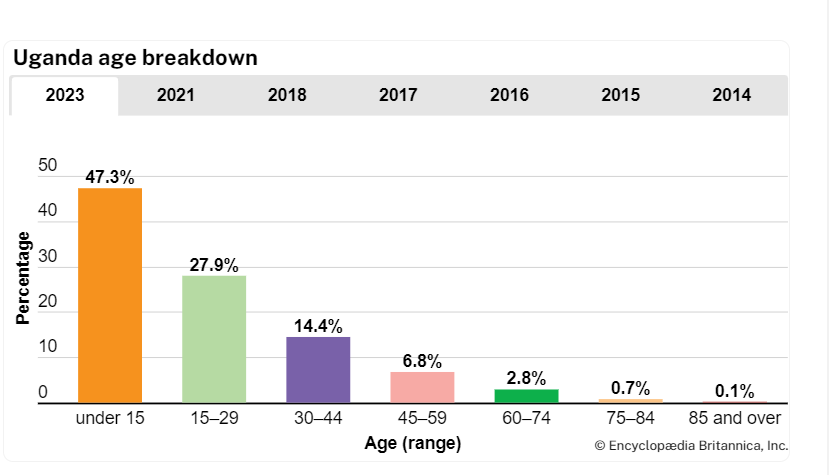

Demographics:

Uganda, like most of Sub-Saharan Africa, is in Stage Two of the demographic transition, marked by high birth rates (36 per 1,000 people) and relatively low mortality rates (6 per 1,000 people) yielding a rapidly growing, youthful population. Essentially, Uganda is experiencing the benefits of medical advances, reducing infant mortality, without the lower birth rates that typically follow industrialization and urbanization.

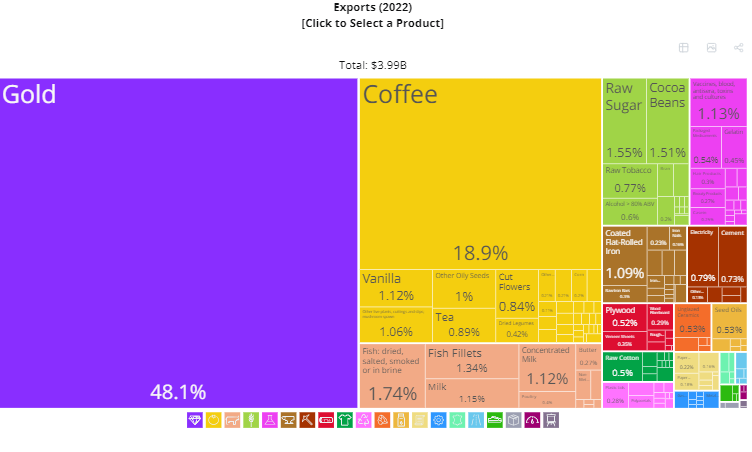

Trade:

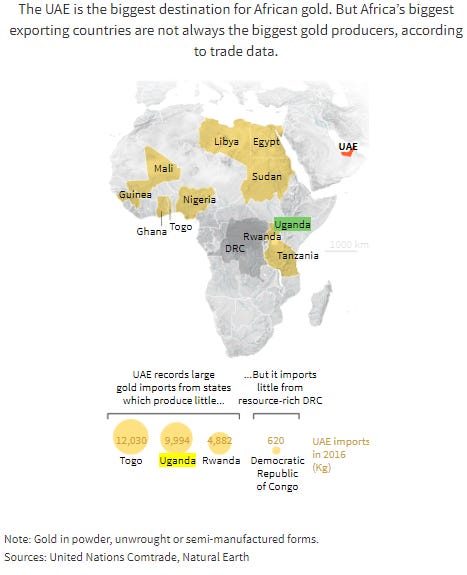

Uganda primarily imports goods from the EU, China, and Kenya. Since 2018, gold has overtaken coffee as the top export, generating over $1 billion annually, with most of it sent to the UAE for refining.

Uganda ranks 58th globally in gold production, trailing other African nations like Ghana, South Africa, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Tanzania. The issue with Ugandan gold mining, like in other African countries, is the untracked, artisanal mining with all the child labor, safety hazards, human rights abuses, and tax losses (via smuggling) that comes with it. High levels of toxic mercury pose severe health risks. Many Ugandans turn to mining to supplement their income, especially to cover school fees. The government and NGOs are working to promote "responsible artisanal mining." Here’s a video to learn more:

As of 2019, 90% of Uganda’s gold production came from artisanal mining, with the remaining 10% from industrial operations (i.e. China’s Liaoning Hongda Enterprises). Additionally, smuggling of gold from the Democratic Republic of Congo is rampant, with Ugandans selling it as Ugandan gold. In fact, the Central Bank of Uganda admits that only 10% of gold exports come from local Ugandan mines. We know this problem exists in Uganda because the UAE reports importing far more gold from Uganda than Uganda produces, highlighting the scale of smuggling.

Besides gold exports, in terms of services, Uganda also generates $1B from tourism.

But also, Uganda discovered oil in 2006. Due to massive logistical nightmares, the oil will finally be extracted by 2026.

Agriculture:

In most African countries we have observed, we have seen a very sad pattern. Africa has an abundance of arable land but terrible farm yields due to the prevalence of subsistence farming. Uganda is a tad different, having found success in certain areas. Ugandan farmers have gotten worse at growing wheat when they were originally great at growing the crop and have poor yields on potatoes, cassava, and rice. But Ugandan farmers have decent yields for beans and corn.

Pre-Colonial Uganda

Bantu Africans settled in present-day Uganda around the 4th century BC, drawn by the reliable rainfall of the Lake Victoria Basin.

By the 12th century AD, the Kitara Kingdom had centralized in the region. However, we lack written records from Kitara’s time—what we know comes from British explorers & anthropologists who documented oral histories, much of which seem mythical.

What we do know is that Kitara’s economy was pastoral, with wealth measured in cattle, alongside farming and iron smelting.

By the 13th century, the Bunyoro Kingdom emerged as a military power, subsuming Kitara, experiencing cycles of stability and civil wars.

By the 14th century, the Buganda kingdom, which was initially a vassal of Bunyoro, emerged as a powerful force on the Northern Shores of Lake Victoria.

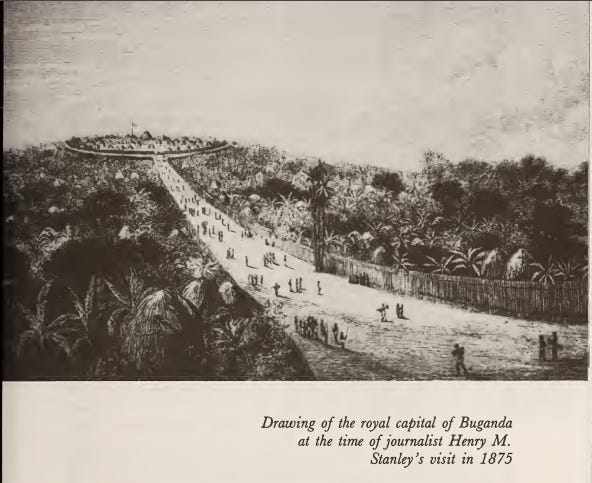

Buganda was highly centralized under a Kabaka (King). They cultivated bananas, millet, and raised livestock, with an organized tax system and even built their own roads. With war canoes, their navy patrolled Lake Victoria and their army expanded Buganda’s influence at Bunyoro’s expense by the mid-19th century. Buganda became the most advanced kingdom in the region. The Buganda & Bunyoro were rivals that competed for domination.

These traditional African Kingdoms of Uganda were not impacted by the European transatlantic slave trade, which affected West, Central West Africa, and Portuguese Mozambique. The lack of African Kingdoms getting guns from Europeans to conduct slave raids on rival Kingdoms allowed the Buganda to have their own unadulterated regional imperialism.

Around the 1800s, a third Kingdom centralized called the Ankole Kingdom. They focused on cattle herding, pastoralism, and farming. They were originally a vassal of the Bunyoro but they broke away.

The Toro Kingdom emerged in the Rwenzori Mountains after breaking away from Bunyoro.

By the mid-1800s, three non-European forces influenced mass-slavery in the region.

The 1st group of slave raiders, were the Afro- Omani Arab Swahili traders from Zanzibar Island. They sold firearms, clothes, and beads for ivory and slaves, supplied by Buganda, who raided neighboring territories. The Omani Arabs also spread Islam and the Swahili language. Current President Museveni of Uganda apologized for Uganda’s complicity in the slave trade in 2023.

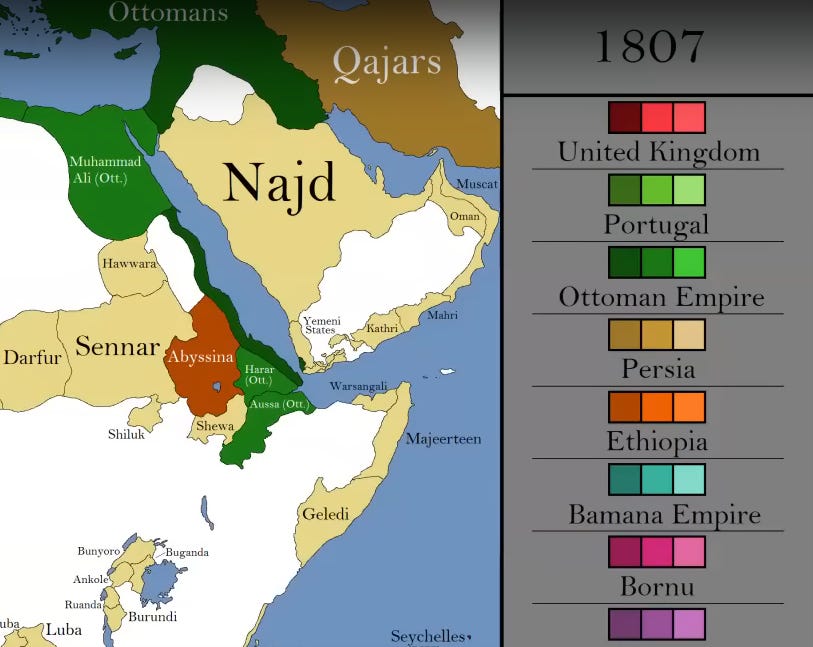

In northern Uganda, where decentralized tribes like the Lango and Acholi lived, Ethiopian merchants, but more significantly, Egyptians enslaved Africans during their imperial expansion under the Khedive of Egypt. Egypt sought to dominate regions that now include Sudan, South Sudan, Djibouti, Eritrea, parts of Somalia, and northern Uganda.

“You are aware that the end of all our efforts and this expense is to procure negros. Please show zeal in carrying out our wishes in this capital matter.” —Mohammed Ali Pasha, ruler of Turkish Egypt

Bunyoro was also partly conquered by Khedive Ismail, who sent Egyptian and Sudanese slave raiders into modern-day South Sudan and northern Uganda. Egyptian flags flew over Bunyoro as their armies raided for ivory and enslaved Africans.

Had it not been for the Mahdist revolt in Sudan, Egypt might have conquered Buganda, but the uprising shifted Egypt's focus to suppressing Sudan.

By the late 1800s, Europeans, particularly Christian missionaries, opposed slavery, aiming to end it, spread Christianity, and introduce Western lifestyles to Africans—what they called the "White Man's Burden." Europeans justified colonialism in Uganda by claiming it was preferable to Arab slavery. As one British observer said:

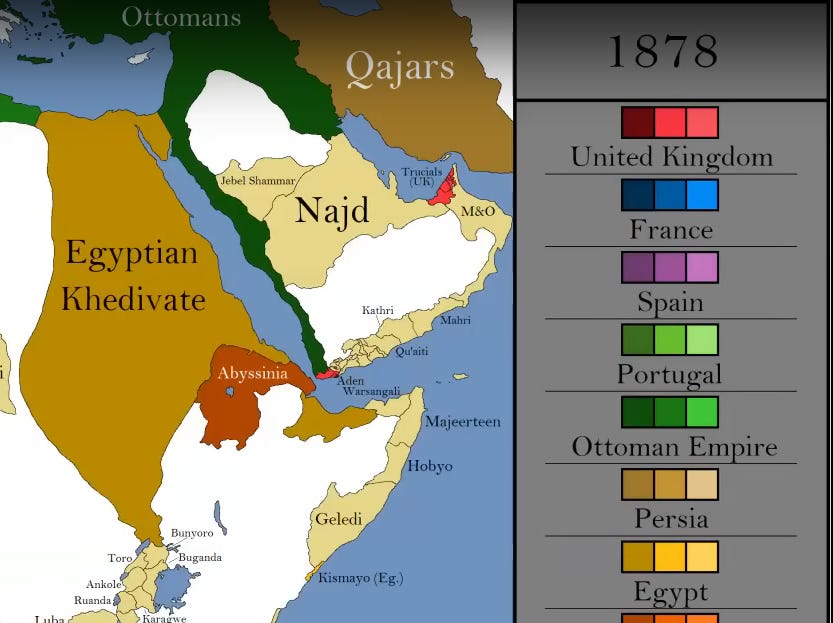

By 1882, Britain controlled Egypt and a few years earlier they encountered the Buganda and other Africans in the region. The British spoke well of Buganda and ill of other Africans in the region, showing there was already massive differences in development within African regions.

British explorer Henry M. Stanley met with King Mutesa I of Buganda, forming an alliance with Britain. Buganda, along with Jubaland in South Sudan, Kenya, and other decentralized chieftains around the region was incorporated into the British East Africa Company, a private firm with a monopoly charter to develop infrastructure and export resources.

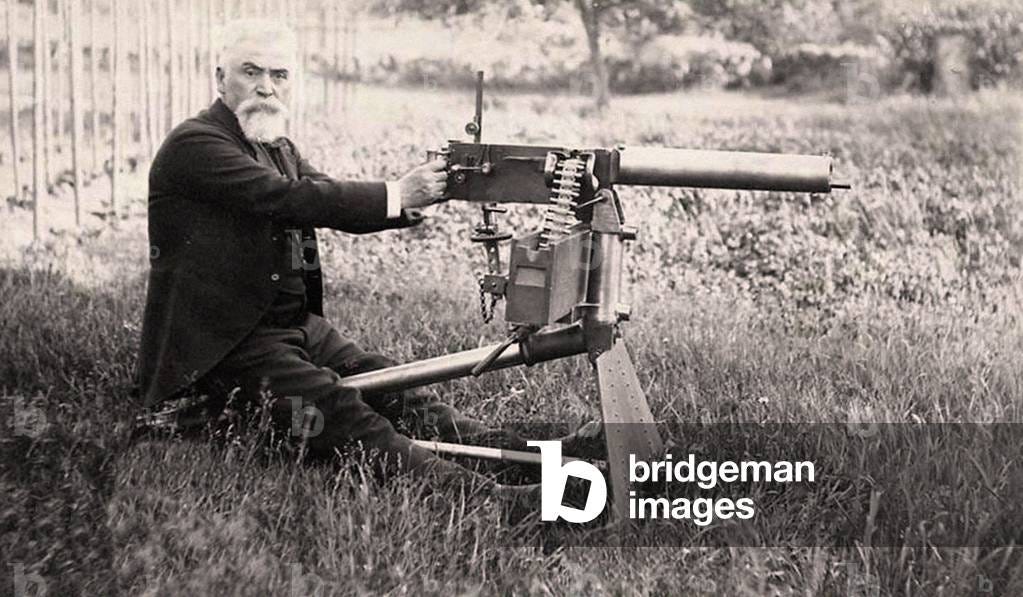

By the 1880s, three religious factions emerged in Buganda: British-supporting Protestants, French-supporting Catholics, and Omani Afro-Arab-supporting Muslims. In 1888, the Bugandan king, fearing religious influence, expelled converts, sparking a civil war. Muslim forces briefly took control but were defeated by Christian factions. Buganda became a Christian kingdom, only to face another civil war between Protestants and Catholics. The British government, finding the company unprofitable, intervened by helping the Protestant Bugandans with a Maxim machine gun, quickly killing Africans and securing their victory.

The Maxim gun solidified British control, and the British government dissolved the British East Africa Company due to financial struggles in quelling rebellions.

With Buganda troops and support from British-controlled Sudan, Britain conquered more territories. Bunyoro, which had avoided religious strife, was occupied by British and Bugandan forces. Other regions, like Ankole and Busoga, signed treaties, while the decentralized tribes in the east, north (Acholi), and northeast were subdued by military force.

Territories were restructured into colonies like Kenya and Jubaland, while Britain arbitrarily combined Buganda with Bunyoro, Toro, Ankole, Busoga, Acholi, and other decentralized villages into the Protectorate of Uganda in 1894—a misspelling of Buganda, their favored kingdom. Unlike Kenya or Sudan, Uganda was a “Protectorate,” like UAE or Qatar, with the Bugandan King (Kabaka) remaining as a ceremonial figurehead. Bugandan tribalists often claimed, “We were never conquered by the British we invited them in”.

Colonial Uganda (1894-1962)

The protectorate of Uganda was run on a meager budget, and had Sudanese mercenaries as law enforcement.

Uganda was set up to grow cotton, bananas, & coffee. Northern Uganda, was largely pastoral, lacked infrastructure like ports or railways, and had subpar soil, limiting economic opportunities. The Southern lowlands had more developed Kingdoms since antiquity due to the more nutrient rich soil. Many northern Ugandans sent their children to work on plantations or in cities in the central or south in Buganda.

In 1897, Sudanese mercenaries revolted, and the Bugandans proved their loyalty to the British by suppressing the uprising. As a reward, Britain granted Buganda significant autonomy within the protectorate and awarded them half of Bunyoro’s land, including sacred burial grounds for Bunyoro kings. This "lost territory" remained a source of grievance for Bunyoro, festering into the 1960s.

Buganda, the most developed region in Uganda, attracted farmers seeking better opportunities. Its schools were more advanced, it had better roads, & it also had political clout, sparking jealousy among other tribes. Uganda was ruled through indirect British control, with local Bugandan chiefs acting as tax collectors. In exchange, chiefs were granted private land. The 1900 Buganda Agreement imposed taxes on huts and guns, and similar agreements followed in Toro (1900), Ankole (1901), and Bunyoro (1933). Buganda, acting as Britain’s sub-imperialist force, collected taxes from other regions, creating resentment among the non-Buganda tribes.

Buganda enforced its language, Luganda, and its clothing, the kanzu, as symbols of civilization, banning traditional attire from other tribes. Buganda people also became missionaries, spreading Protestant Christianity throughout Uganda.

Unlike Kenya which had significant European settlement, Uganda barely had any. This left agriculture largely in the hands of Africans if they responded to the opportunity. The British also brought South Asian migrants from Punjab or Gujarat villages to make railways or support administrative and commercial activities. In 1901, the completion of the Uganda Railway (aka the “Lunatic Express”, coined for its enormous cost) from Lake Victoria to Mombasa spurred colonial authorities to push for cash crop cultivation to help cover the railway’s operating costs.

The South Asians dominated the economy even more than Bugandans. South Asians worked as traders, shopkeepers, and jewelers, filling a niche in the commercial middle class. Over time, they dominated various sectors, including retail trade, money lending, construction, and textile manufacturing. South Asian traders often operated in towns and villages, helping to develop the country's economy and trade networks. South Asian entrepreneurs made huge corporations like the Madhavani Group, which later accounted for 10% of the Ugandan Protectorate’s GDP. The Mehta Group from Gujarat made the Sugar Corporation of Uganda.

Africans became envious of South Asian success. South Asians in Uganda were a “dominating, middle-man minority”, just like Jews in Europe, Igbos in Nigeria, or Chinese in Southeast Asia.

Buganda, with its strategic location near the lakeside, thrived in cotton production, and Buganda chiefs grew relatively wealthy by employing tenant farmers to work on their cotton fields. By 1905, Buganda exported 2,200 pounds of cotton; by 1915, exports soared to 2.4 million pounds. This turned Uganda into a profitable colony, no longer needing British subsidies. Buganda’s success in cotton production outpaced other regions like Busoga, Lango, and Teso. Bugandans spent their earnings on imported clothes, bicycles, metal roofing, and cars, and prioritized education, leading to the growth of schools across Buganda and Baganda people becoming the literate class.

Bunyoro, however, suffered under Baganda dominance. They lost land, culture, and were forced into unpaid labor and taxation. In 1907, the Bunyoro revolted in the "nyangire" (refusing) rebellion, successfully driving out Baganda agents.

With education and military training, Baganda people secured top jobs (like the military) and formed the Young Buganda Association. Tenant farmers eventually used their wages to buy land from Baganda landlords, and new markets, like coffee, created additional economic opportunities. Unlike neighboring Tanganyika, devastated by the East African campaign in WWI, Uganda prospered through wartime agricultural production. However, the Great Depression hit Uganda hard, with global demand for coffee and cotton plummeting.

In response to fluctuating commodity prices, the British established state-owned marketing boards that controlled the purchase and sale of agricultural commodities. South Asian traders, who were favored by the British as intermediaries, were given significant control over the trade and export of these commodities. They would buy products from Ugandan farmers, often at low prices set by the boards, and sell them abroad at a profit. South Asians also played a significant role in Uganda’s sugar industry, and many preferred to hire laborers from Kenya and Tanganyika over Ugandans, exacerbating local tensions.

Ugandans didn’t want to just export cotton, Ugandans wanted to gin cotton. But British and South Asians stopped Africans from participating. With a cotton gin, South Asians exported more cotton than Ugandans. The Africans got mad and would sometimes kill South Asians.

Then WW2 happened, and after mass riots for more autonomy, Britain was preparing Ugandans for independence. Britain appointed an African Ugandan to Uganda’s first legislative council in 1945, but representation was “weighted”; one European representative or one Asian representative was equivalent to two African representatives.

By 1949, frustration boiled over in Buganda, where protesters burned down the houses of pro-British chiefs, demanding three key changes: the liberalization of the cotton market, the end of South Asian monopolies on cotton ginning, and the right for Bugandans to elect their own local representatives rather than having British-appointed chiefs.

By 1952, new reforms came into play. The colonial government allowed Africans to have their own cotton gins, made more hydroelectric dams, removed price controls on Ugandan coffee, built new roads, introduced cement manufacturing, allowed Ugandans to form cooperatives, made more high schools, and made the Uganda Development Corp to finance new projects.

Coffee production soared, becoming Uganda’s most valuable export by 1957.

In 1953, Governor Cohen wanted to combine Uganda, Tanganyika and Kenya in a Federation, just like Britain did with Rhodesia & Nyasaland (Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi). But Ugandans (especially the Bugandans) did not want an East African Federation because they knew it would be dominated by the white settlers in Kenya, which was engaged in the Mau Mau rebellion at the time.

The King of Buganda, the Kabaka, Mutasa II threatened to declare independence unilaterally if Uganda was incorporated into the East African Federation. Mutesa II also resisted Britain’s democratic reforms which made Andrew Cohen the governor, delegitimize Mutesa II’s kingship, and exile him to Britain, kickstarting the Kabaka crisis of 1953.

This led to mob violence as Bugandans wanted their king back and independence. Britain brought the King back, and Mutesa II accepted limits on his monarchial powers in 1955.

In the late 1950s, a few political parties emerged and they wanted independence. A group of Buganda made a party called Kabaka Yekka (King Alone) who wanted Buganda to be independent or Buganda to lead Uganda.

A Catholic, anti-monarchy Buganda group, also emerged called the Democratic Party, led by Benedicto Kiwanuka. Yet another party emerged called the Uganda National Congress (UNC) in 1952, but UNC couldn’t get over their provincialism. Another Ugandan who rose the ranks of the UNC was a Lango-ethnic named Milton Obote, who splintered off the UNC and made his own leftist party called the Uganda People’s Congress (UPC).

Some Africans in Uganda hated the South Asians and wanted South Asians to be excluded from citizenship so it would be easy to kick them out and seize their property. There were mass rallies of Anti-South Asian expression.

Before independence, due to neighboring Burundi and Rwanda becoming Hutu Supremacist, they kicked out some their Tutsis which fled to Uganda, causing more issues.

After all the chaos, Uganda had its first election in the national assembly in 1961. The Catholics in the Democratic Party won the first election with Benedicto Kiwanuka as the first Prime Minister in the first year before independence. But there would be another election in 1962.

In order to get the Buganda vote, Milton of UPC promised the Buganda King that he would be President, while Milton would be Prime Minister.

In 1962, another election happened, the UPC won in an alliance with the King’s Kabaka Yekka, making Milton Obote Prime minister and Mutesa II was the President & King and it received independence.

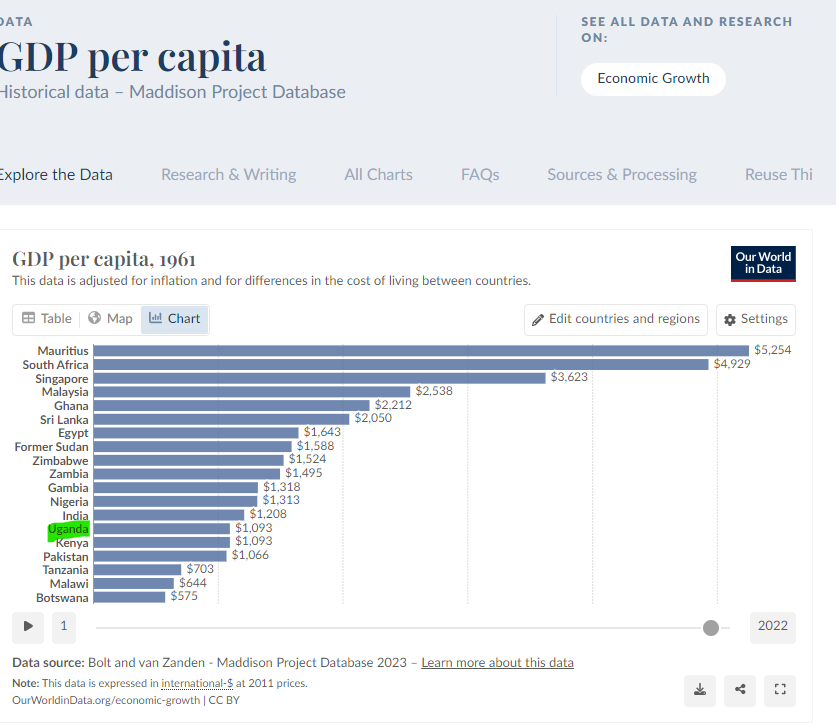

On the eve of independence there were 6.5M Africans, 71K South Asians, 2K Arabs, 11K Europeans, and 1.3K mixed people in Uganda. By 1962, Uganda was pretty poor compared to most British colonies.

Concluding thoughts

Studying Uganda raises a question: Would African countries have developed more without the European Transatlantic Slave Trade?

Uganda wasn’t impacted by the European transatlantic slave trade because it was landlocked and Europeans couldn't access the interior of Africa before the medical revolution of the 1800s, which provided quinine (from Brazilian tree bark) to combat malaria. The region was known as the “White Man’s Grave” until this discovery. Meanwhile, Omani Arabs, Egyptians, and the Ottoman Turks dominated most of East Africa, and Europeans didn’t gain overwhelming technological superiority over these Muslim empires until the 19th century. Until then, European Empires were concentrated in West Africa, West Central Africa, and Mozambique in East Africa.

Even without European involvement, Uganda had unindustrialized, centralized kingdoms like Buganda and Bunyoro in the south and decentralized chieftaincies in the north. However, even the most developed kingdom, Buganda, impressed Britain due to its political centralization, not because of any technological advancement. When Britain allied with Buganda, Buganda still lacked the industrial technologies—like Gatling guns, telegrams, or steamships—that gave Britain such an overwhelming advantage.

Also, Uganda was still raided for slaves by Egyptians & Omani Arabs before British rule. Even without European slavery, African kingdoms still faced enslavement and external threats and were unindustrialized—a scenario that applied to places like South Sudan, Chad, and the Central African Republic as well. Read Part II here.

Informative article. Great illustrations.

Great article!