The CFA franc is a currency that France gives to it former colonies. CFA originally meant “Colonies Francaises d’Afrique” (French Colonies in Africa), but now it means “Coopération financière en Afrique” (Financial Cooperation in Africa).

Pascal Airault & Jean-Pierre Bat, in Françafrique: Secret Operations and Affairs of State assert that “No French president has wanted to let go of his reserved African domain, the veritable DNA of the presidency under the Fifth Republic"

It is currently debated whether French Africa should keep the currency or not. Here are some viewpoints:

On the Anti CFA Franc side: “Debating the merits of the CFA franc”, says Guy Marius Sagna, a Senegalese activist, “is like discussing the advantages and disadvantages of slavery.”

On the Pro CFA Franc side: President Ouattara of Ivory Coast says “The fact that we are pegged to the euro, if we borrow euros, by the time to repay them in five or 10 years, the rate is fixed.” and “The false debate needs to stop as the CFA Franc is stabilizing for our countries”.

So, who is right?

The CFA franc represents neocolonialism to the French speaking African youth. But to proponents, they see the CFA franc as a bulwark against inflation or a balance of payments crisis which has plagued non-CFA nations like Ghana. Both things can be true at the same time. However, that doesn’t mean the CFA franc should still exist.

Also, it’s worth noting that participation in the CFA franc is completely voluntary (ostensibly…). Guinea left in 1958, and Guinea was famously ransacked by the French after Guinea voted independence. Mauritania and Madagascar left the CFA franc in 1973 and all three never looked back. Mali left the CFA franc in 1962 and rejoined in 1982. Mali tried maintaining a peg to the CFA franc. Mali couldn’t hold the peg, and devalued the Mali Franc in half, doubling the price of imported food, medicine, and manufactured goods for Malians. By 1982, Mali rejoined the CFA Franc.

After WW2 ended, France made the CFA franc for two monetary zones: one for West Africa and one for Central Africa. You can see the two zones below.

History of the CFA Franc

After WW2, Europe could not hold on to its colonies. France fought brutal wars trying to maintain Algeria and Indochina (modern day Laos, Cambodia, & Vietnam).

Charles de Gaulle, the president of France at the time, managed a crafty slight of hand. Instead of complete independence in French Africa, de Gaulle created a community of African nations that share a currency made by France. In the late 1950s, de Gaulle offered French Africa total independence or an offer in the French Community in a referendum vote on September 28th, 1958. With the exception of Guinea, and later Mauritania & Madagascar, all French West & Central African countries joined the French Community.

The CFA franc used to be pegged to the French franc, but since France joined the European Union in 1999, the CFA franc is now pegged to the euro, with convertibility guaranteed by France. When Ivory Coast sells cocoa and Senegal sells gold, the dollars/euros/yen they earn are pooled together in the Central Bank of West Africa in Dakar, Senegal. When Gabon sells manganese and Cameroon sells oil, the African countries pool their foreign currency in the Central Bank of Central Africa in Yaounde, Cameroon. Both their central banks get their monetary policy from the Bank of France in Paris. In addition, a French official sits on the board of the West & Central African regional bank.

For both the West & Central African regional bank, half of their foreign exchange is deposited in the French treasury. In return, the French treasury pays .75% interest to the Francophone African nations and the African nations can access the funds in the French treasury whenever the African nations want to. The plus side for France in this arrangement is that when French Africa exports its resources and obtains foreign reserves (dollars/yen/pounds), French Africa loans that money to France at an absurdly low rate of 0.75%. Since inflation in French Africa is higher than 0.75%, this is a negative yield for French Africa. Also since French inflation always exceeds the 0.75% France pays out to French Africa, this means France basically gets free money from French Africa’s commodity export profits. The plus side for French Africa is that they have the money they need parked in France in case commodity prices become too low and thus lose the ability to buy volumes food, medicine, manufactured goods, or fuel. Since France is way more powerful than French Africa, the French African youth sees this as power asymmetry and neo-colonialism.

Meanwhile, Ghana and Nigeria abandoned UK’s currency in 1958 & 1973 respectively.

Since we are talking about economics, we are talking about trade offs. Every economic benefit that the CFA franc provides also comes with an additional downside.

CFA Franc: Exchange Rate Protection and Inflation Bulwark:

Because African nations don’t make enough food, medicine, manufactured goods, or refined fuel for themselves, they have to import those goods from abroad. As a result, inflation in Africa is dependent on exchange rates. If the naira weakens to the dollar, then it will cost more for Nigerians to buy jet fuel from America.

Non-CFA franc African countries don’t have good track records of fiscal and monetary discipline. ~20% inflation, currency devaluation and depreciation have been the norm in non-CFA nations like Ghana, Nigeria, Gambia, and Sierra Leone. Whenever there is a currency devaluation/depreciation, the purchasing power of the people, especially the poor, is crippled. In 1995, Nigeria’s currency, the naira, was valued at 86 naira to a dollar. Today it takes 760 naira to make the same transaction.

Meanwhile, France has only devalued the CFA franc once in 1994. They devalued the CFA franc to franc exchange rate from 50 CFA = 1 CFA franc to 100 CFA franc to 1 franc, doubling inflation for the whole Francophone area in one year. The 100% inflation in a year caused by France in 1994 caused violent clashes, murderous riots and protests in Ivory Coast, Senegal, and Gabon. The plus side of devaluation is that it makes the French African nations’ exports more attractive because they are cheaper, but the downside is that imported goods (machines, fuel, food, malaria drugs) become more expensive.

Lastly, Equatorial Guinea, a former Spanish colony, purposely joined the CFA franc in 1984, and it helped them. Before 1984, Equatorial Guinea experienced annual inflation rates between 38% to 84%! Now Equatorial Guinea’s inflation hovers around 3%. Also, Guinea-Bissau, a former Portuguese country, can’t handle high inflation anymore and willingly chose to join the CFA Franc in 1997.

Inflation, over the past 50 years, in CFA-nation Ivory Coast has averaged 6% inflation while non-CFA Ghana has had 29%. This is because by anchoring the CFA franc to the Euro and forcing the countries to put 50% of their reserves on hold, during moments of capital flight, French countries have a stronger ability to defend their currency from capital flight compared to non-French countries. Despite the CFA franc helping CFA African nations with inflation, the true benefit goes to French multinational companies. Here’s how:

Benefits for French multinationals over African Small-Medium sized enterprises:

French firms like Bollore, EDF, Total, and Veolia could invest in Gabon, Senegal, Ivory Coast, and etc. knowing that their CFA franc revenues wouldn’t depreciate because the CFA franc was fixed the the Franc (later Euro) because the French treasury held euro reserves to sell euros to buy back CFA franc to keep the CFA franc strong. In short, the CFA franc protects European investors from exchange loss risk.

Strong currency:

France purposely made the CFA franc strong, making it easier for the French African countries to import food, fuel, or medicine. This also makes it easier for the French African elites to import luxury items.

However, having a strong currency means that Francophone Africa’s goods are too expensive to purchase internationally, hampering industrialization.

Lack of sovereignty:

“Psychologically, with regards to the vision of sovereignty and managing your own money, it's not good that this model continues” — Patrice Talon, President of Benin, a CFA franc country

When countries are hampered by external shocks, Ghana and Nigeria’s central bank is able to devalue its currency to protect foreign exchange. The Francophone countries have zero power to do that. Since the CFA franc is pegged to the Franc, and then later euro, monetary policy basically set by the Eurozone. Since Germany is the biggest exporting economy in the Eurozone, monetary policy for French West & Central Africa is really set by Frankfurt, Germany!

The downside of devaluation though, is that Ghana and Nigeria experienced massive inflation by making their currencies (the cedi/naira) to need more of them to buy a dollar worth of goods. Nigeria and Ghana have had multiple devaluations. As mentioned before, the newly independent CFA franc nations have only had one devaluation.

In addition, non-CFA franc countries can use their central banks to raise or lower their interest rates. Out of fear of capital flight, the Ghanaian or Nigerian central bank will raise interest rates to make the cedi or naira more attractive. The non-CFA franc nations don’t have that luxury. If the EU wants to curb economic growth to stop inflation they will raise interest rates, which will strengthen the currency of the euro and thus strengthen the CFA Franc. But this could be happening at a time when the CFA franc really wants to weaken their currency to export more goods to the world. The EU and CFA union’s economic interests are not aligned. Now I will discuss some misnomers about the CFA franc.

What leaving the CFA franc doesn’t mean:

Just because nations leave the CFA franc doesn’t mean they’ll experience fast economic growth. There’s not really much of a difference in growth rates between CFA Africa and non-CFA Africa. This is because the underlying problem of African growth is dependence on exporting commodities, which have volatile prices. Also, being on the CFA franc doesn’t mean a CFA country experiences less balance of payment crises. Again, the underlying cause is commodity price volatility.

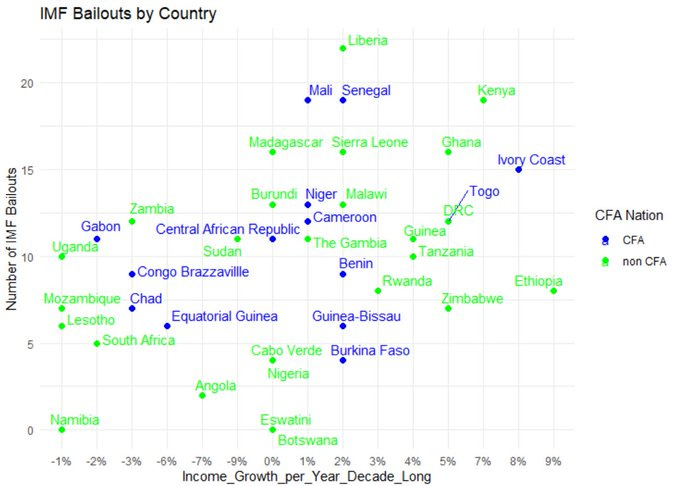

Below is a graph that shows income growth from 2011 to 2021 on the x-axis and # of IMF bailouts on the y-axis for CFA and non-CFA countries. There’s no relation between economic growth and being on the CFA franc (CFA nation Ivory Coast had the 2nd best economic growth of Sub-Saharan Africa, while CFA nation Gabon had declined on average 2% per year every year for 10 years. For Gabon, the decline had more to do with the post-2014 oil bust.)

This means that Chad or Congo-Brazzaville’s poor economic performance over the last decade has very little to do with the CFA franc, otherwise how can you explain the high growth of Ivory Coast and Togo? This is because the oil prices collapse post 2014, affecting Chad and Congo-Brazzaville.

Additionally, leaving the CFA franc isn’t a cure-all panacea for economic growth. The growth of CFA nations and non-CFA nations on the aggregate is very comparable.

Overall, the CFA franc doesn’t need to exist, but removing the currency will not suddenly spur economic growth in the CFA regions. Sure, it helps control inflation and it artificially gives French West & Central Africa an easier time importing goods, but the true beneficiaries are the French Treasury & French multinationals. A nation can’t evolve if it doesn’t learn to make decisions itself. Next time, we will discuss the alternatives to the CFA franc.