Guns, Germs, & Cobalt Q&A #9: Insights on Botswana, Chile, Peru, China, and Morocco

What Peru’s guano, Chile’s saltpeter, and Botswana’s diamonds teach us about innovation killing monopolies.

Hi everyone, I received several questions by email, in the comments section, and through private chats, so I’ve compiled this Q&A. Also, check out Critical Perspectives, that Substack will have their own version of this topic as well.

#1 What’s Going on in Botswana?

Botswana is taking a dangerous gamble. The current president, Duma Boko, wants his government to buy a controlling stake in De Beers, the global diamond giant, this October 2025.

This deal could happen. Anglo American PLC, the mining conglomerate that owns De Beers, is looking to divest its stake to potential investors.

Right now, De Beers’ value has declined to $5B. Botswana already owns 15% of De Beers ($750M). To control 51% ($2.55 billion), Botswana needs an additional $1.8 billion. The government is negotiating with Oman’s sovereign wealth fund to help finance this acquisition.

But the timing couldn’t be worse. Botswana’s economy contracted in 2024 and is projected to shrink again this year due to collapsing diamond prices. Debswana, the joint venture between De Beers and Botswana, saw revenues plunge roughly 50% in one year in 2024. Boko believes “resource nationalism” will help save Botswana, but he’s betting the country’s future on a dying industry.

#2 Can you give me a brief history of Botswana?

For decades, Botswana was Africa’s quiet “success story”. It was one of the few Sub-Saharan countries with living standards higher than some Latin American or Eastern European countries.

The secret was diamonds and not being foolish with them.

When vast deposits were discovered in the late 1960s after independence, Botswana struck a joint-venture deal with De Beers to create Debswana. Unlike Sierra Leone or the Democratic Republic of Congo (then called Zaire), where diamond nationalization bred corruption and mismanagement, Botswana let De Beers handle mining and marketing while the government collected half the profits plus taxes.

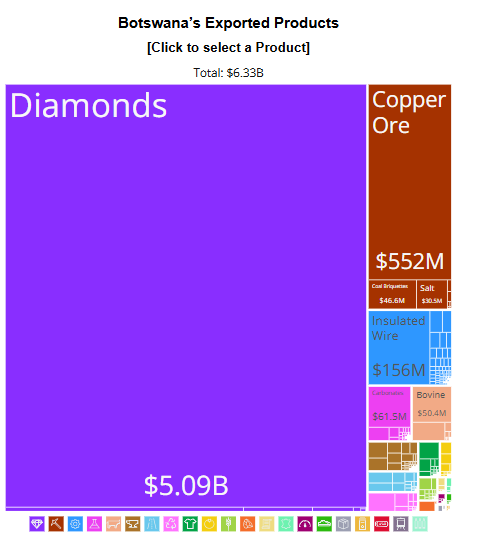

The strategy worked brilliantly. Diamonds made up a third of state revenue and most of its foreign-currency earnings.

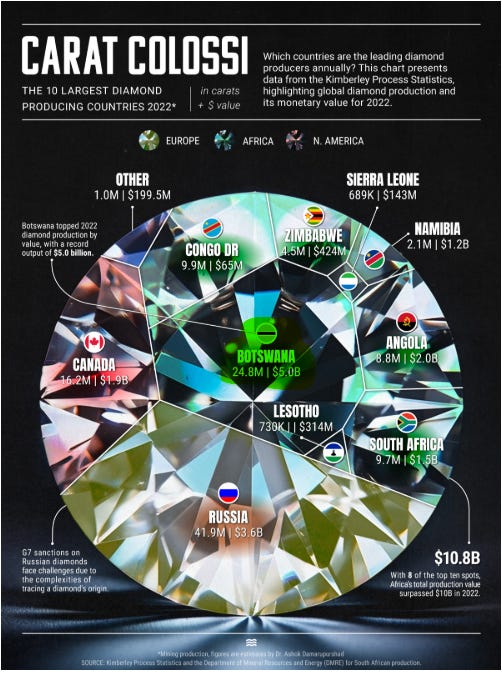

By dollar value, Botswana is the largest diamond producer on earth, selling $5B in diamonds in 2022.

#3 Why Did Botswana avoid Africa’s Common Pitfalls?

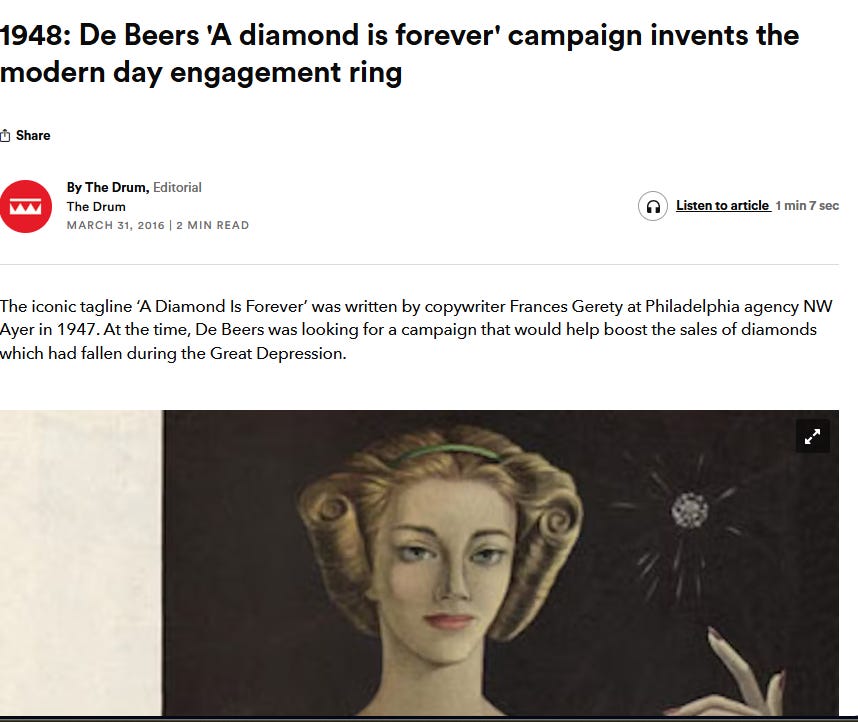

De Beers, founded in 1888 by Cecil Rhodes, once controlled 90% of global diamond sales through a cartel. The company hoarded gems in London vaults to restrict supply and raise prices, while its legendary Madison Avenue campaign—”A Diamond Is Forever”—artificially sustained demand.

This marketing brilliance convinced generations of middle-class women that a diamond engagement ring was a necessity, transforming a luxury into a cultural requirement.

That mix of diamond marketing and price-fixing enriched De Beers and saved Botswana. While other African economies were ravaged by collapsing commodity prices in the 1980s and 1990s, Botswana’s diamond revenues stayed stable because De Beers kept prices artificially high.

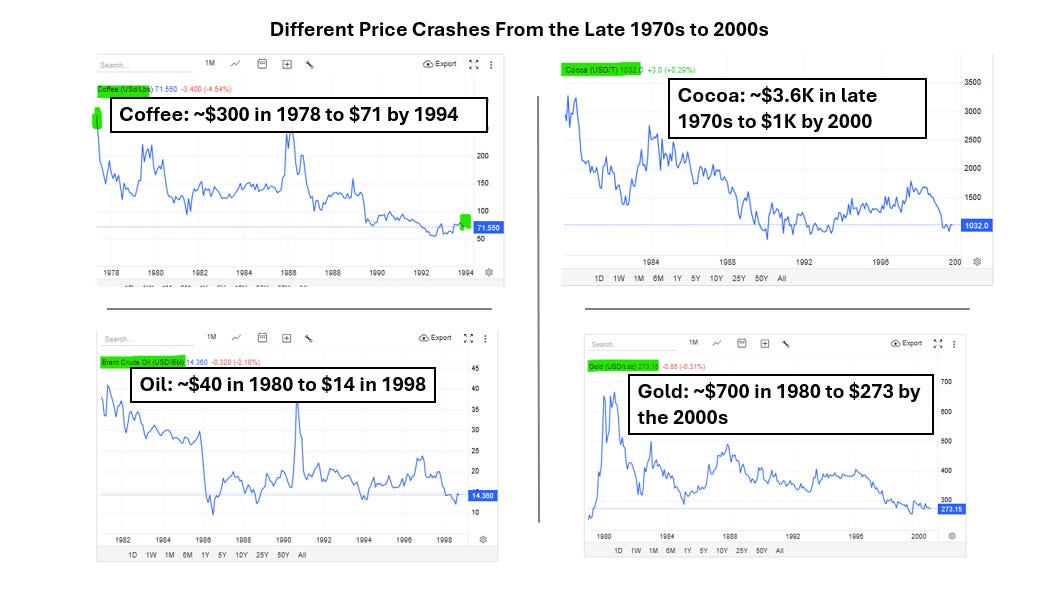

Each commodity crash devastated the countries that depended on it. Below you will see how prices crashed for coffee, cocoa, oil, and gold. They all collapsed around the 1980s and didn’t recover until the 2000s.

You tell me the resource and I’ll tell you when it crashed.

Cocoa Crash in late 1970s? Hurt Ghana and Ivory Coast

Coffee Crash in the late 1980s? Hurt Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, Ethiopia, and Ivory Coast

Gold crash in 1980s? Hurt Ghana

Copper Crash in the 1980s? Hurt Congo and Zambia

Recessions for advanced economies in the early 1980s and the flood of post-Soviet Union countries joining international markets for the first time (Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Azerbaijan) in the 1990s crushed commodity prices, bankrupting many African governments. This caused the two-decade-long African Debt Crisis (~1980 to 2000). Most of these countries requested IMF bailouts and endured two decades of stagnation until China’s demand for commodities revived prices in the 2000s.

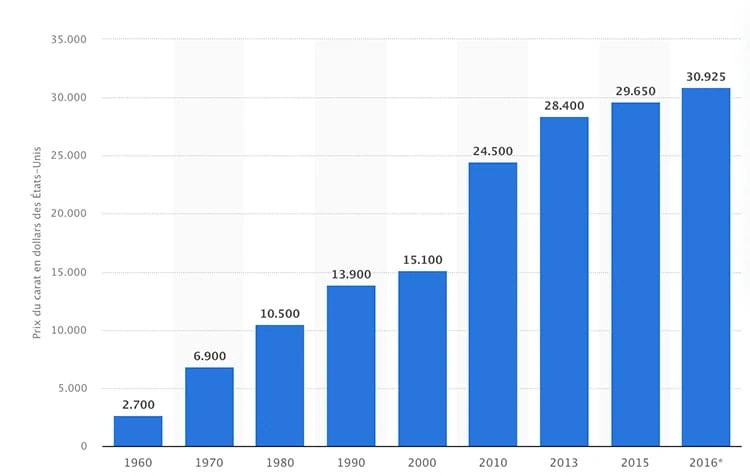

However, diamonds never had this problem. Diamond prices kept rising throughout this period, because De Beers maintained its cartel. This is the real reason Botswana never needed an IMF loan. Not because it was a democracy with “inclusive institutions,” as Why Nations Fail argues, but because it benefited from an artificial monopoly. Look below to see how diamond prices never crashed in the 1980s or 1990s:

#4 If De Beers is such a global monopoly, then why is Anglo American trying to divest its stake in De Beers?

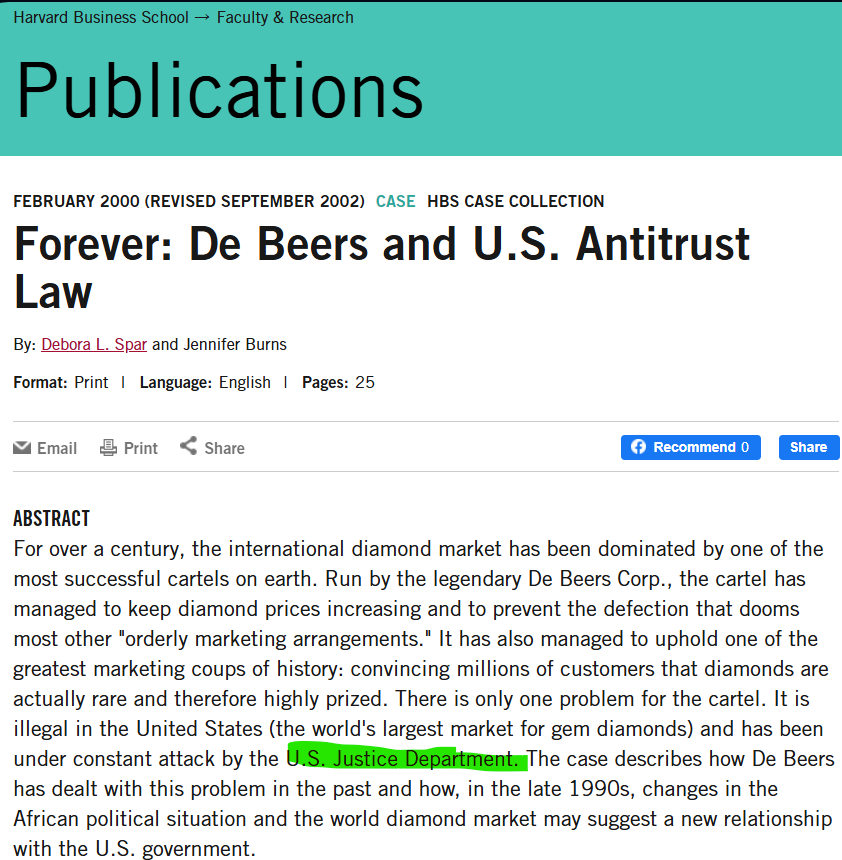

De Beers’ dominance ended in 2000 after U.S. antitrust lawsuits forced De Beers to abandon its monopoly practices.

De Beers went from a publicly traded company to a private firm in 2001 under a consortium led by Anglo American, the Oppenheimer family, and Botswana’s Joint venture with De Beers, Debswana. In 2004, the government converted its indirect stake into a direct 15 percent ownership of De Beers alongside its 50 percent share of Debswana — a shrewd move by the African country that secured long-term influence over the industry.

But two decades later, the model is unraveling. De Beers’ market share has fallen to about 33%, and Botswana’s economy remains perilously dependent on diamonds, which still account for ~75% of foreign exchange earnings and 33% of its government revenue.

Now diamond prices are crashing, creating more pain for Botswana.

#5 Why is there a Natural Diamond Price Crisis?

It stems from China — twice over.

First, Chinese demand collapsed. In 2015, China imported $8 billion in diamonds globally. By 2023, that figure had fallen to less than $5 billion, with further declines projected. The CEO of Lucara Diamond Corp. bluntly admitted recently that: “The market in China is dead.”

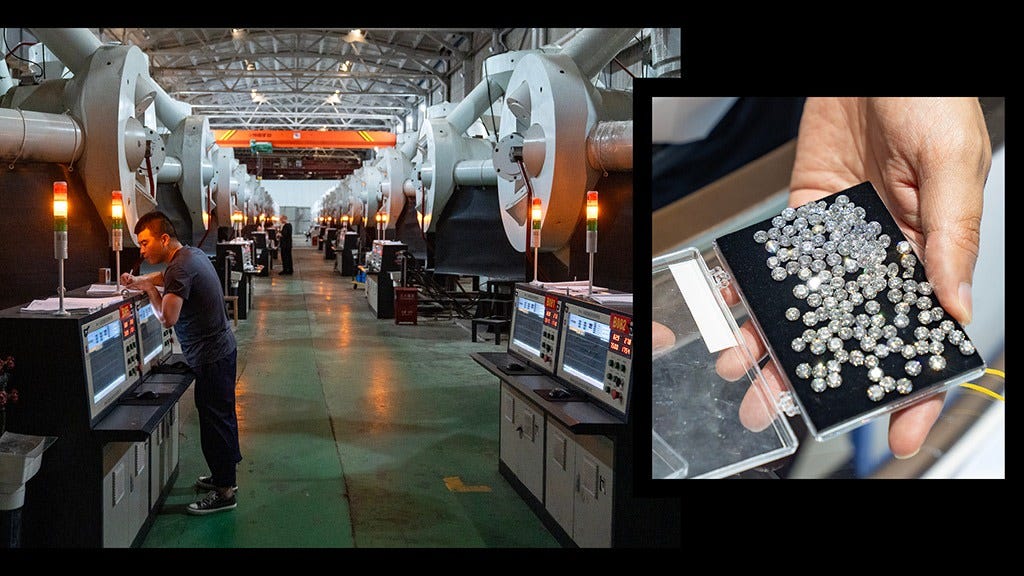

Second, Chinese manufacturers now flood the world with lab-grown diamonds that are chemically identical to mined stones.

China’s synthetic diamond industry dates to Chairman Mao. After the Sino-Soviet split in the 1960s severed trade ties, Moscow cut off industrial diamond supplies. With virtually no natural reserves, Mao directed state enterprises toward synthetic production. China produced its first lab-grown diamonds in 1963.

After Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, China’s lab-grown diamond industry expanded rapidly, especially in Henan province.

Initially focused on industrial applications, Chinese firms like Jiaruifu in the 2010s pivoted to jewelry—a higher-margin market. Today’s synthetic diamonds aren’t fake cubic zirconia; only a spectrometer can distinguish them from natural stones.

Today, over 70% of lab-grown diamonds for jewelry come from Chinese factories.

The impact has been devastating. Lab-grown diamonds’ global market share rocketed from 4% in 2018 to roughly 20% in 2023. In the United States, the world’s largest diamond market, lab-grown stones now represent 50% of all diamond purchases.

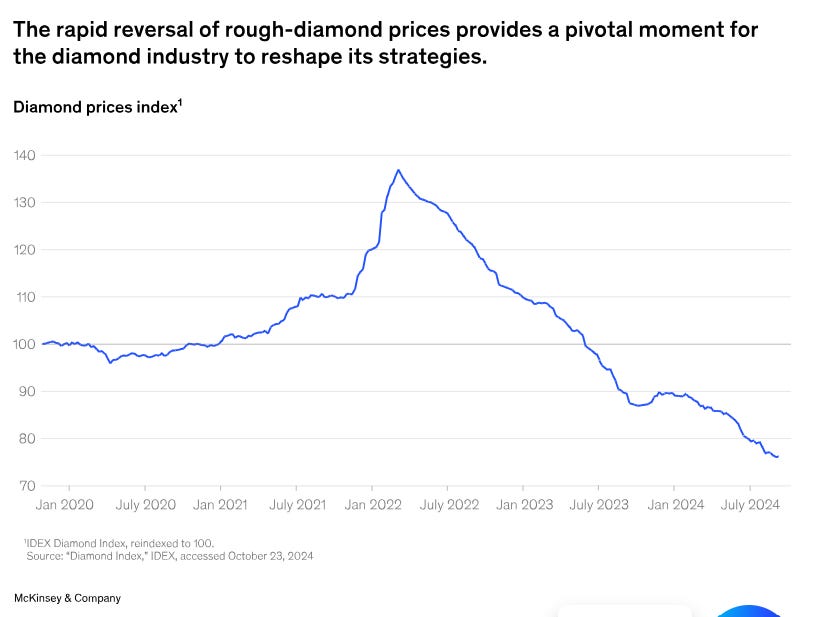

Because lab-grown stones cost 90% less than natural diamonds for the same quality, they’ve become a perfect substitute. Prices have plunged since 2023, see graph below:

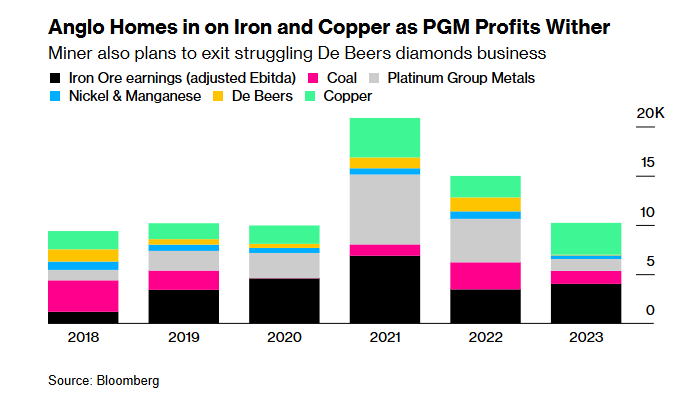

As prices plunge, De Beers’ profits have collapsed. Anglo American responded with a restructuring plan to exit diamonds, coal, and platinum and focus on copper and “green-growth” metals. BHP Group declined to acquire De Beers, judging natural diamonds a dying business.

Look below at the graph of Anglo American, its parent company, of De Beers. If you see the graph, De Beers’ profits (yellow) have shrunk to almost non-existence in 2023. The natural diamond business is terrible right now.

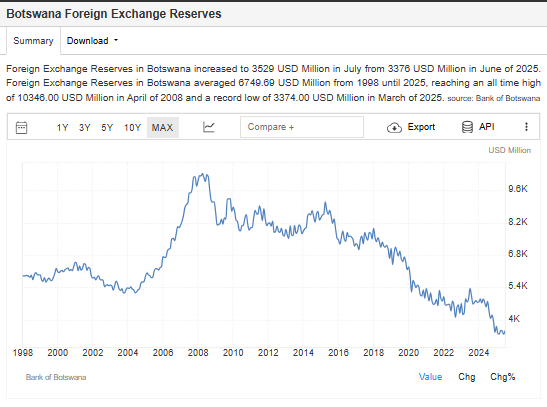

The consequences for Botswana have been severe. From De Beers losing its monopoly in the early 2000s to natural diamond prices tanking in the 2020s, Botswana’s FX reserves fell from $10 billion in 2007 to $3.5 billion today—less than Botswana held in the 1990s.

With $3.5 billion in reserves and roughly $7 billion in annual imports ($600 million monthly), Botswana has approximately six months of import coverage ($3.5B/ $600 per month). While not yet emergency territory (under three months is dangerous), the trend is alarming. If Botswana’s reserves fall below three months of import coverage, it will need its first-ever IMF loan. Also, living standards have declined since 2023. Vice President Ndaba Gaolathe warns: “Something drastic has to be done—we must live within our means.”

President Boko inherited this crisis after Botswana’s first change in ruling political party since independence, ending decades of dominance of the Botswana Democratic Party. His government hired Malaysian consultants to design diversification plans and claims $12B in Qatari investment pledges.

Boko is right to pursue diversification and foreign investment. But his decision to buy a larger equity stake in a collapsing industry is a catastrophic mistake. Boko urged anyone “who is in love and who wants to get married” to shun engagement rings with synthetic stones.

Boko seems trapped in the old faith that resource nationalism equals sovereignty, and sovereignty equals prosperity. But commanding a resource that’s losing value is no sovereignty at all. Botswana is facing its first commodity price plunge that other African nations faced in the 1980s & 1990s and have experienced again post 2014.

Botswana’s problem isn’t unique. History is full of nations that bet their future on a single resource—right before technology made it worthless.

#6 Have there ever been examples in Economic History where a Materials Engineering Innovation has substituted for a Real Commodity?

Yes… Many times. Economic history is full of warnings about how materials innovation can destroy a nation built on one commodity.

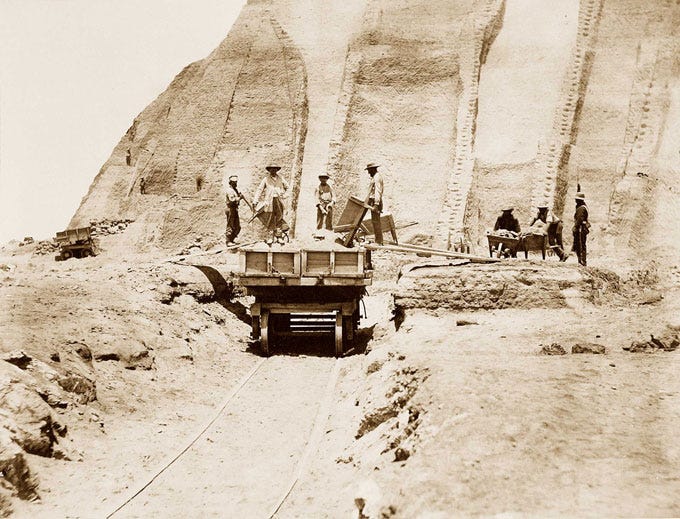

In the 1800s, Peru bet its existence on guano—seabird, bat, and seal droppings rich in nitrates and phosphates.

As the Industrial Revolution accelerated, European & US populations urbanized rapidly. Fewer people were farming, and fewer farmers had to feed growing urban populations. To feed these growing cities, the remaining farmers had to grow more food on the same land — planting crops every year instead of letting soil rest. This intensive cultivation drained essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium from the soil.

Traditional fertilizers, like animal manure and compost, weren’t enough to restore soil fertility. The fear was that crop yields would fall, leading to fears of global food shortages. Economists like Thomas Malthus predicted catastrophe. He could not imagine that the world could sustain 1 billion people in 1804.

That’s when Peruvian guano or “white gold” provided the solution. Good fertilizer requires nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus, and guano was extraordinarily rich in all three. The nitrogen concentration—~15%—far exceeded any European manure or compost, and Peru’s dry coastal desert preserved centuries-old deposits 100 feet thick on the Chinchas islands.

This sparked the “Great Guano Craze” of the 1850s. The US passed the Guano Islands Act in 1856, authorizing American claims to any uninhabited territory containing guano deposits.

But Peru possessed the most abundant guano sources, and it transformed Peru’s economic prospects.

The Peruvian government paid off ALL former debts, even nationalized the trade and took foreign loans against future Guano income.

Peruvian bird poop made national engineering institutes, build railroads & massive public projects, and modernized the military. Guano was 60% of Peru’s government revenue.

Spain even invaded the Chincha Islands to seize the deposits, triggering the Chincha Islands War (1864-1866). Peru, allied with Chile, Ecuador, and Bolivia, repelled Spain.

But the boom was short-lived. The most nutrient rich deposits were depleting by the 1870s and when the Global Financial Crisis of 1873 hit, Europe and America were in depression, so demand for Guano slumped. Peru tried raising prices by restricting supply, but high Guano prices drove European and American farmers towards cheaper, lower quality fertilizers such as Chilean saltpeter (sodium nitrate). Demand for Peruvian Guano evaporated and was replaced with Chilean saltpeter.

Peru transformed overnight from a solvent, growing nation into a debt-ridden wreck. Peruvian President Manuel Pardo defaulted on sovereign debts in 1876. Banks collapsed. One historian wrote: “[Having had] unlimited access to London credit… [but now] saddled with Latin America’s largest foreign debt, Peru was unprepared for the crash. It was riches to rags, with nothing to show in persisting economic advance.”

During this period, over 30 attempted uprisings took place in Peru after 4 years.

Desperate, Pardo eyed Chile’s nitrate fields so Peru can monopolize the resource. This miscalculation led to the War of the Pacific (1879-1884), technically triggered by a Bolivian tax dispute but fundamentally about nitrate deposits. Chile declared war after Bolivia violated a treaty by taxing Chilean nitrate companies in Antofagasta. When Bolivia moved to confiscate the Chilean company’s assets, Chile invaded. Bolivia invoked its defensive alliance with Peru, and the war began.

Chile crushed both adversaries, annexing Tarapacá (Peru’s main nitrate region) and Antofagasta (Bolivia’s Pacific outlet). Chile then monopolized natural sodium nitrate (saltpeter), riding a commodity boom. Chile had 80% of global market share. Saltpeter fueled fertilizer and gunpowder production, enriching Chile. But something interesting happened in the 1910s.

German scientists Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch developed the Haber-Bosch process, synthesizing ammonia directly from atmospheric nitrogen and hydrogen.

This great breakthrough enabled synthetic fertilizer production anywhere. The world no longer needed to fight wars over bird poop or saltpeter. All you needed was natural gas.

The Haber-Bosch process didn’t immediately kill Chile. World War I temporarily sustained Chile’s nitrate industry through explosive demand. But in the 1920s-1930s, synthetic fertilizers gained market share. The Great Depression delivered the fatal blow. Chile’s exports fell, GDP contracted, and Chile defaulted in 1931.

Peru’s guano islands and Chile’s nitrate mines became worthless. Boko’s natural diamonds will be heading in that direction soon.

I can name so many examples of this. Chemistry and materials science are the biggest killers of resource nationalism. Technological breakthroughs can render a previously vital resource obsolete:

Nazi Germany, followed by the US and USSR mass produced synthetic rubber, which displaced natural rubber from British Malay & Ceylon (Malaysia & Sri Lanka)

Synthetic dyes created by German chemists in the 1850s-1880s destroyed natural indigo cultivation dominance in British India

Petroleum-based plastics developed in the early 1900s replaced ivory British East Africa

President Boko’s push to buy more of De Beers echoes Peru and Chile’s tragic bets on guano and saltpeter—doubling down on a commodity just as technology renders it obsolete.

Lab-grown diamonds are doing to Botswana what synthetic fertilizer did to Peru and Chile: collapsing prices and exposing how fragile mono-export economies are. It’s sad watching history repeat itself.

#7 Has there ever been examples in Economic History where there was diversification in Africa?

The lesson here is diversification. Now, you might ask. “But Yaw, can you tell me an African country that diversified its exports?”

Yes. But success comes in levels. Since independence, African countries have followed different paths away from colonial export patterns. Understanding these levels reveals why some diversification attempts succeed while others merely shuffle deck chairs.

Level 0: Countries that Have the Exact Same Exports as Colonial Times

Some countries still export exactly what they did under colonialism—just more of it. Malawi exports mainly raw tobacco like it did in the early 1900s. Zambia mainly exports copper, its colonial staple.

But colonialism isn’t even the determining factor. Ethiopia, the sole African country that was never colonized and defeated the Italians in 1896, still mainly exports the same commodity it did in the 1800s: coffee beans. Despite avoiding colonization in the 1800s, Ethiopia’s main export remains unchanged from the 19th century—though today it also sells other goods like textiles.

Ethiopia’s story shows that internal institutions can be as limiting as foreign rule. Serfdom/tribute payment (Gabar) and slavery (Bariya) persisted deep into the 20th century, keeping most of the population bound to landowners. Emperor Menelik II introduced telegraphs, founded Addis Ababa as the new capital, built a modern army, and pursued other reforms, but Ethiopia never underwent a Japanese-style Meiji Revolution that kept the Emperor while abolishing noble privileges and spurring rapid industrialization.

For example, serfdom and slavery were not abolished in Ethiopia until 1942, which shows that it’s not always an external power holding a nation back. Sometimes a country can hold itself back. Instead of a Japanese-style Meiji Revolution, it endured a Russian-style Communist Revolution in the 1970s.

The communist Derg military government finally ended that last remnants of feudalism in 1975. However, the Communist Derg military government’s disastrous policies—forced villagization and communal farming—sparked ethnic rebellions that nearly tore the country apart. Ethiopia didn’t emerge as a stable unit until 1993 after Eritrea seceded, and even then, ethnic militias and the flawed 1995 federal constitution keep instability alive.

Despite these challenges with no structural changes in exporting goods, Ethiopia has become extremely successful in exporting services. Ethiopian Airlines has become highly profitable and is the nation’s largest source of foreign currency. In service exports, Ethiopian Airlines earns nearly five times what Ethiopia makes from coffee bean exports.

Level 1: Replacing one Low-Value export with another

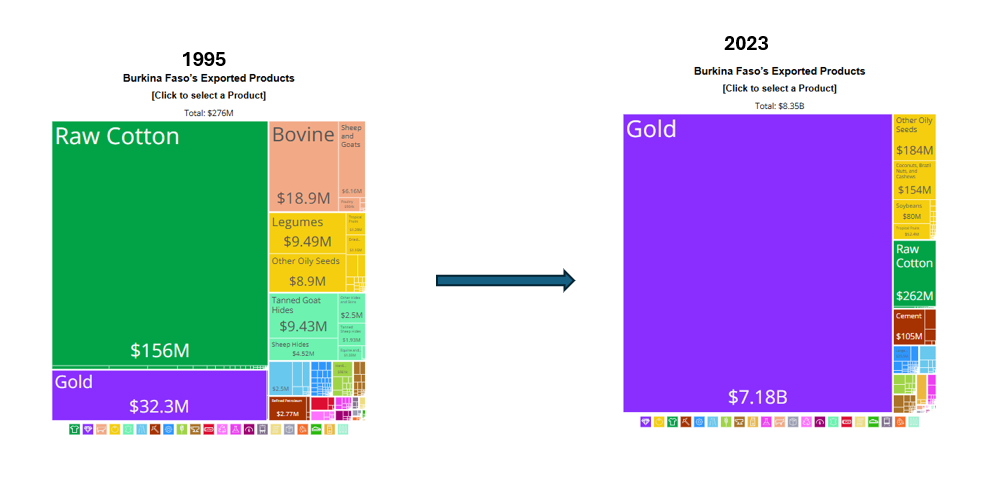

Several countries swapped one unprocessed commodity for another. Burkina Faso and Mali switched from raw cotton (colonial times through the 1990s) to raw gold (2000s onward). Look at Burkina Faso’s export history below:

Mauritania moved from mainly selling gum arabic in colonial times to iron ore (1960s) to gold (today). Niger pivoted from peanuts and livestock to uranium (1970s) to gold (late 2010s). Chad and Sudan both transitioned from cotton since colonial times to crude oil in the 2000s. But after Sudan lost South Sudan, its main export went to gold.

This is the worst form of “diversification.” Switching from cash-crop exports to mining exports doesn’t create industrial capabilities or meaningful linkages. Mining is capital-intensive, not labor-intensive—it employs few people and generates little knowledge transfer. Economists call this “horizontal export replacement without upgrading.”

Botswana fits here. Before independence: cattle. After independence: diamonds. Same pattern, different commodity.

Level 2: Partial Diversification to Backsliding

Some countries began upgrading in the 1990s only to regress. Senegal offers a cautionary tale. From colonial times, Senegal exported mainly peanuts and fish. In the 1990s, it processed primary goods—peanuts into peanut oil, phosphate into phosphoric acid. But today Senegal’s main exports are raw gold and re-exported refined fuel landed at its port for landlocked neighbors. Senegal has a refinery, but most refined petroleum exports are simply re-exported imports. That’s logistics arbitrage, not production or industrial learning.

Level 3: Partial Diversification

Two countries achieved meaningful but incomplete transformation:

Tunisia: Colonial exports were phosphates and olive oil. Post-independence added tourism and briefly crude oil. Through export-processing zones and auto-supplier networks, Tunisia built light-industry capacity. By the 2000s, it manufactured cables, wires, and textiles. These are actual industrial products requiring technical skills.

Egypt: During the Pasha Dynasty (1800s), 70% of export earnings came from selling raw cotton to Europe. Under British occupation (early 1900s), this worsened to 90%. Synthetic fibers crushed demand, but Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal and courted foreign investors for oil and gas exploration. By the 1980s, crude oil and gas comprised 60% of export revenues and Suez toll fees were a great addition. By the late 2000s, Egypt added refined petroleum, nitrogen fertilizers, and petrochemicals—moving up the value chain from extraction to processing.

Level 4 – Structural Diversification with Knowledge Transfer

Only two African countries achieved genuine structural transformation:

Mauritius: From colonial times through the 1960s, Mauritius basically only exported sugar. Export processing zones (1970s-1980s), tourism promotion, and offshore financial services transformed the economy. Today: textiles, tourism services, and financial products. Mauritius branded itself as “Africa’s Singapore,” marketing directly to Hong Kong textile firms and Indian IT companies. The strategy worked because branding created differentiation.

Morocco: From colonial times through the 1970s, phosphates generated most foreign currency. But Morocco built industrial clusters, trained technicians, developed R&D capabilities, and invested in ports and energy infrastructure. Special economic zones attracted automotive and aerospace manufacturing.

The trajectory tells the story: In the 1990s, Morocco was a sweatshop economy mainly selling textiles to Europe. By the 2010s, it exported cables, fertilizers, cars, and textiles to Europe. By the 2020s, aerospace parts became a top export. Morocco didn’t just diversify—it climbed the technological ladder and became an appendage of Europe.

#8 Why Did some countries succeed while others failed?

Nearly every African country since the 1970s has attempted industrialization through special economic zones, ISI, export promotion, or R&D plans. The difference isn’t whether they tried, but how they executed.

Geography matters. SEZs only thrive when exports can reach large, stable markets efficiently. European firms build car and wire plants in Morocco or Tunisia—not Mali or Niger—because North Africa offers proximity to Europe and access to Mediterranean ports.

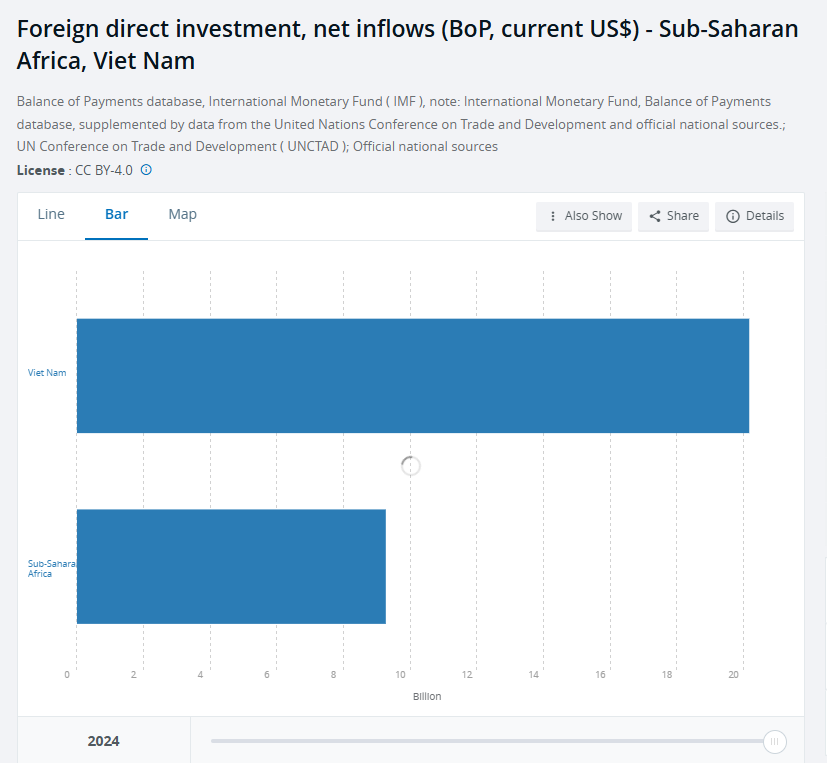

Branding matters. Tunisia sold its “Mediterranean middle-class” image to French and Italian manufacturers and had a free trade deal with the European Union since 1998. Mauritius pitched itself as “Africa’s Singapore.” Other African countries simply advertised cheap labor. Low wages aren’t enough, you need a productive workforce, decent infrastructure, and consistent electricity as well. This is why Vietnam receives more than double the net FDI (inflows minus outflows) than all of Sub-Saharan Africa combined.

Institutional capacity matters. Successful diversification requires competent civil services insulated from military and patronage networks. Without capable bureaucracies, SEZs become corruption schemes rather than growth engines.

The lesson is clear: diversification protects against technological disruption, but only if executed strategically with realistic advantages. Botswana is wasting precious resources and political capital borrowing a fortune to buy into a dying industry.

Personally, I bought a lab-grown diamond for my fiancée — and she loves it.

Once again I learn things here that I would be unlikely to come across anywhere else. Your writing and use of graphics are top notch as well. And congratulations on your engagement!

Fascinating history of these important economic drivers in countries like Botswana, Peru and elsewhere. Excellent!