The Remastered Economic & Geopolitical History of Nigeria Part 1: An Overview of Nigeria and an Introduction to Nigeria's Pre-Colonial States

The country that was destined to be divided from day 1

Nigeria is a fascinating country packed with ~370 ethnicities and ~500 languages. Nigeria hasn’t collected religious demographics since the 1963 census, but Nigeria is often depicted as evenly divided religiously — a predominantly Muslim North and a predominantly Christian South, alongside a smaller portion practicing their traditional religions. However, due to the North’s higher birth rates, some estimates grok that Nigeria is 54% Muslim, 45% Christian, and 1% other. The capital of Nigeria is Abuja, but the commercial capital is Lagos. Currently, Nigeria is more urbanized than most African nations—54% of Nigerians live in urban areas.

What This Article Covers

By the end, you’ll start to understand:

Why Nigeria is struggling despite huge potential, touching on economic issues, corruption, and human capital challenges.

Nigeria’s deep ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity, and how this complexity shapes the country.

The start of Nigeria’s pre-colonial history up to the 11th century AD.

Nigeria’s Youth and Demographic Challenges

Nigeria has an incredibly young population—the median age is just 18 as of 2025. That’s because Nigeria, like much of Sub-Saharan Africa, is at Stage 2 of the Demographic Transition Model.

Here’s a quick breakdown of the five stages:

Stage 1 (No Medical or Industrial Revolution): High birth rates, high death rates, and poor sanitation. Infant mortality is high, many women die giving childbirth, famine, diseases, & droughts keep the population in check. This was basically all of human history until the UK started the industrial revolution and Europe discarded the old Greek model of “miasma theory” kicked off modern medicine with germ theory and public sanitation in the 1800s.

Stage 2 (Medical Revolution without Industrial Revolution): Death rates drop fast due to better healthcare, sanitation, and food, but birth rates stay high (over 3 kids per woman), causing a population boom—exactly where Nigeria and most of Sub-Saharan Africa is today.

Stage 3 (Medical & Industrial Revolution): Death rates remain low, but birth rates start dropping fast, like we see now in India, Indonesia, and the Middle East, which are now almost at replacement rate (2 kids per woman).

Stage 4 (Advanced Society): Low death and birth rates are below replacement, leading to slow growing population (e.g. America, France). Immigration becomes the main source of population growth.

Stage 5: (Advanced Aging society): People aren’t having enough kids, and the population becomes older, leading deaths to outnumber births—this is what’s happening in Japan and South Korea.

Nigeria: An Invention

"Nigeria" as a unified nation didn't exist until the UK drew the borders.

Nigeria’s name was coined by British journalist Flora Shaw in 1897. Married to Lord Lugard, the British colonial administrator of Nigeria, Shaw suggested to the Times of London the word “Nigeria” to denote the lands around the Niger River controlled by the Royal Niger Company. “Nigeria” literally translates to "land of the Niger River." Read my article on Niger to learn where “Niger” comes from!

Nigeria’s Paradox

Abroad, Nigerians thrive.

According to the US Census Bureau as of 2023, the median Nigerian household earns $80.7K/year, edging out the U.S. national median ($80.6K).

Over two-thirds of Nigerian-American households hold a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Domestically, Nigeria boasts creativity and hustle.

Nigeria’s fintech sector has given rise to vibrant startups like Flutterwave, OPay, Moniepoint, and Paystack (acquired by Stripe).

Nigerian Afrobeats artists such as Burna Boy, Fireboy DML, WizKid, Tems, Tiwa Savage, and more — dominate global music charts.

So why isn’t Nigeria a global success story?

A Contracting Giant

First, a quick caveat: I’m skeptical of Nigeria’s official GDP figures, primarily because over half of its GDP comes from the informal sector—economic activities outside government oversight, such as street vendors, small-scale farmers, and unregistered businesses. Measuring this sector accurately is challenging and given Nigeria’s limited state capacity, these figures likely aren't fully reliable. Now let’s proceed, given these caveats.

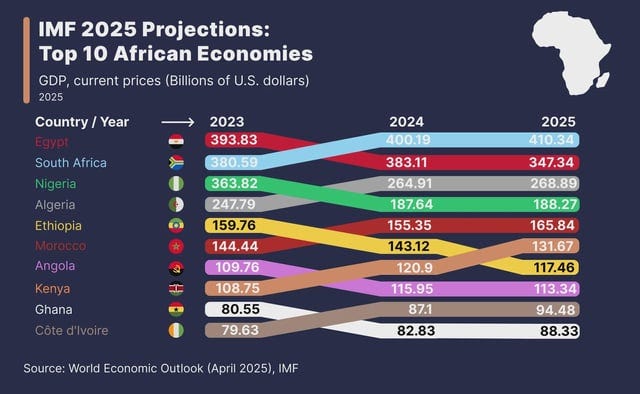

Unfortunately as of 2025, Nigeria is one of the fastest shrinking economies in the world. In 2023, Nigeria’s GDP was roughly $360B. In 2024, it cut in half to $188B and it is projected to stay $188B this year in 2025. Why such a drastic drop?

This sharp economic decline is largely attributable to currency devaluation. In May 2023, the naira to dollar ratio was ~₦460 to $1; by 2025, one dollar was trading for ₦1600.

When Bola Tinubu became president in June 2023, he appointed a new Central Bank governor who shifted Nigeria’s exchange rate policy from a managed naira-to-dollar exchange rate anchor to a managed, floating exchange rate. With less central bank interventions to anchor to the naira to the dollar, the naira lost roughly 70% of its value against the dollar within two years, sharply decreasing Nigeria’s GDP in dollar terms. As a result, Nigeria’s GDP, measured in dollars, dropped significantly—even if its economy continued to grow when measured locally (in naira) or by purchasing power parity (PPP).

This sharp devaluation severely impacts Nigeria because the country buys tens of billions of dollars of imported food and fuel, which is paid in foreign exchange like US dollars. Additionally, Nigeria’s government has dollar-denominated (external) debt that is equivalent to 30% of its GDP. With a weaker naira, servicing these debts becomes increasingly costly, reducing budgetary flexibility. In 2022, interest payments alone consumed about 96% of Nigeria’s federal revenue, forcing even more dollar borrowing. But, besides currency issues, Nigeria has deep structural issues as well.

Structural Issues:

Electricity Crisis: Nigeria has more people without electricity than any other nation (90M), including India, Indonesia, or China. Chronic power outages disrupt hospitals and businesses, forcing them to rely on private generators.

Human Capital Issues: According to the UN’s 2023 Human Development Index, the average Nigerian has an equivalent education to an 8th grader or 14 year old. Why? Many Nigerians, particularly girls in rural northern areas, drop out of school early, dragging down the national average despite some Nigerians completing advanced degrees. This trails behind Ghana/Kenya (average schooling: age 15) and Botswana/Gabon (average age: 16).

Poor Credit Rating: As of 2025, Nigeria’s credit rating is B- (S&P)/ Caa1 (Moody’s), which is considered “highly speculative” or junk debt.

Nigeria’s Land, Resources and Mismanagement

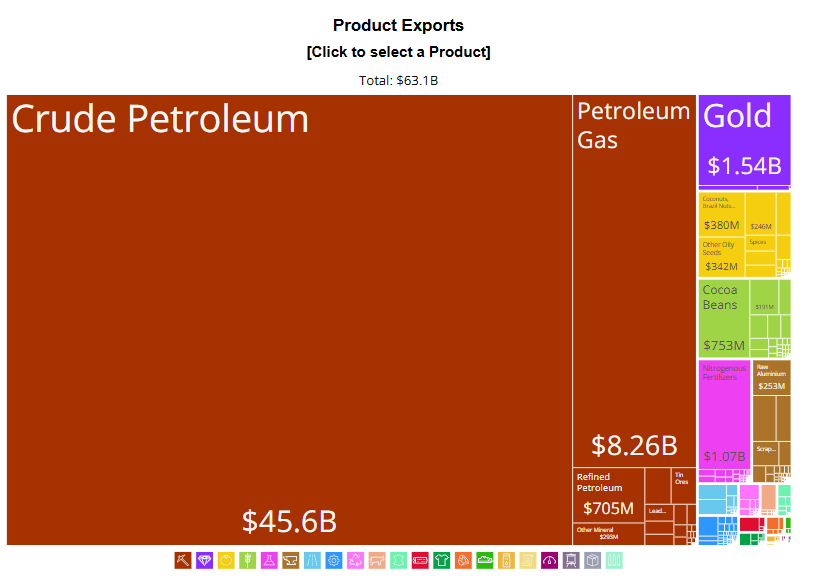

Sadly, Nigeria depends too much on oil, with crude oil exports accounting for ~80% of Nigeria’s foreign exchange earnings and ~67% of government revenue. This makes Nigeria’s economy, growth, and living standards a slave to the international oil price.

Historically, Nigeria’s “golden eras” of growth were the post-Biafra war oil boom (1970-1981) and the “Africa Rising Period” (2000-2014). Every other time has been horrible for Nigeria, including now. Consequently, nations once poorer than Nigeria—like Bangladesh, the Philippines, China, and Indonesia—have since surpassed it economically. See graphs below:

Land & Population:

Nigeria is huge—about 925,000 square kilometers, roughly twice the size of California. That's big enough to stretch from Paris to Prague, or Milan to Amsterdam.

Officially, Nigeria’s population is ~230 million as of 2025. But without a credible recent census, skeptics—including myself—think the real number might be closer to 160-200 million.

Even Nigeria’s former National Population Commission said:

“No census has been credible... Even the one conducted in 2006 is not credible. I have the records and evidence produced by scholars and professors of repute; this is not my report. If the current laws are not amended, the planned 2016 census will not succeed…” (He was fired for speaking out).

Nigeria was supposed to do a census in 2023, but it was postponed… Even as of May 2025!

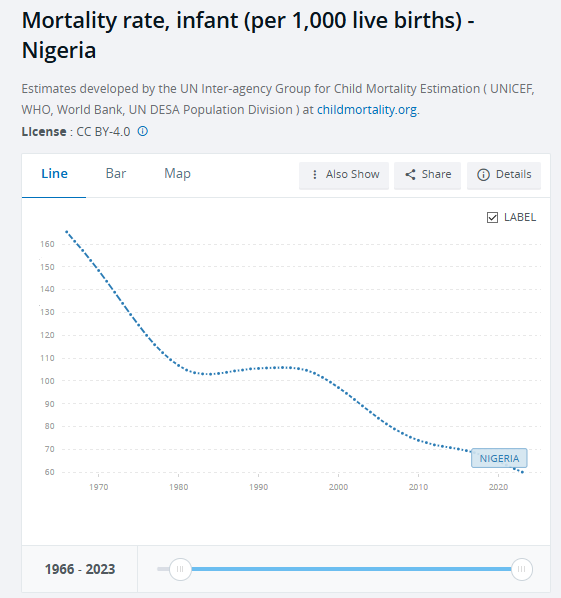

Much of the issue with population collection is political. You see, Nigeria also struggles with one of the lowest tax revenues (as a share of economic output) globally—even low by African standards. Remember, two-thirds of the government’s money comes from oil exports. The federal government then distributes that oil money to states and local governments based on their population size. This creates an incentive for states to inflate their population numbers—exaggerating fertility rates, downplaying child mortality, ignoring emigration, and generally manipulating their data to claim a bigger share of oil revenue.

Resources

Nigeria has tons of fertile land and is the world’s top producer of cassava and yams, plus Africa’s largest rice producer. But it still seriously underachieves in farming—most Nigerian farmers remain stuck at the subsistence level.

The numbers tell a grim story. Nigerian yields for staple crops like rice, maize, or wheat are pretty terrible. In fact, Nigeria’s average crop yields (measured in tons per hectare) are even lower than the average for Africa and other developing countries that rely on food imports.

Why? In Nigeria, seed quality for farmers is poor, land ownership is informal, and farmers mostly depend on unpredictable rain rather than irrigation.

Compare Nigeria to Vietnam, and it gets stark. Nigeria has five times more arable land, yet Vietnam produces five times more rice.

Nigerian Exports: “Resource Rich” or just “Resource Dependent?

Nigeria’s exports break down into three groups:

Over $10 billion sold: Just crude oil.

Between $1 billion and $10 billion: Gold, natural gas, and fertilizer.

Under $1 billion: Everything else.

But to really understand resource wealth, you need to look at three things: reserves, production, and exports.

Reserves: In terms of oil reserves, Nigeria is #11 in the world.

Production: It’s 15th worldwide in oil production.

Exports: It ranks 10th in global oil exports as of 2023.

For gas, Nigeria is #10 in reserves, #16 in production and exports as of 2023.

But here’s the thing: If you really want to measure how rich a country is in oil and gas, you need to look at exports per capita. In 2023, Nigeria made ~$54 billion annually from oil and gas, with about two-thirds going to the government—but dividing that among ~200 million people leaves very little per person.

Check out the graph below comparing oil exports per capita with average income. The explanatory power (R²) is 74%—meaning nearly three-quarters of the differences in living standards among petro-states can be explained just by how much oil export money the government collects per person.

And here's the bad news: when you compare Nigeria’s oil exports per capita to countries like Norway, Azerbaijan, Brunei, or Libya, Nigeria ranks dead last.

Compare that to truly oil-rich nations like Norway ($122B), Qatar ($91B), or UAE ($113B), each with populations below 10 million — and Nigeria’s per-person oil wealth is modest at best. Rapid population growth (45M in 1960 —> 97M in 1990 —> ~230 million in 2025) has diluted this benefit. Rather than resource-rich, Nigeria is better described as resource-dependent.

To make matters worse, Nigeria faces much higher oil extraction costs than other major producers like Saudi Arabia, the US, and Norway, significantly eroding its profits. As of 2024, Nigeria spends $48 per barrel to extract oil, compared to $9 in Saudi Arabia, $21 in Norway, and $24 in America. With global oil prices around $60 per barrel, Nigeria sees much smaller profits per barrel.

Nigeria’s higher costs come primarily from its reliance on offshore and deep-water fields in the Niger Delta, which are far more expensive to operate than Saudi Arabia’s easily accessible onshore reserves or America's shale fields. This doesn't even include additional losses from rampant oil theft by criminal groups—a major issue covered in a separate article [here].

Lastly, Nigeria hasn’t managed its oil money well. Its sovereign wealth fund, created only in 2012, has just about $2.4 billion—much smaller and newer than funds in other oil-producing countries. (Saudi Arabia made theirs in 1971 and UAE made theirs in 1976).

But that’s enough about modern day, let’s discuss pre-colonial Nigeria.

Pre-Colonial History

Pre-colonial Nigeria was a mosaic of diverse kingdoms and cultures, broadly categorized into three regions.

Northern Nigeria: Home to groups like the Fulani, Hausa, Kanuri and more. This region had powerful states such as the Kanem-Bornu empire, Hausa city-states, and the Sokoto Caliphate. The land is savanna and semi-desert (the Sahel). It’s full of cows and produces cotton and peanuts. Currently, this area has terrorists like Boko Haram and Islamic State-West African Province (ISWAP).

Middle Belt Nigeria: Populated by groups like the Borgu, Nupe, Tiv, and Igala. This region features hills, plateaus, and diverse cultural traditions.

Southern Nigeria: Dominated by ethnic groups such as the Yoruba in the Southwest, Edo in the South-South, and Igbo, Ijaw, Efik, and Ibibio in the Southeast. This region has dense forests and swampy terrain around the Niger Delta, which is Nigeria's oil heartland—though, unfortunately, most local communities don’t see the benefit of the oil money.

Nok Civilization (1000 BC to 500 AD)

The first prominent civilization recorded in Nigeria’s Middle Belt was the Nok, who lived around the Jos Plateau. They were early iron-smelters, famous for their detailed terracotta sculptures and iron tools.

Sadly, the Nok vanished from history without leaving behind any written records. We only know about them because British archaeologists rediscovered their artifacts during colonial times.

8th Century AD

Northern Nigeria

Kanem-Bornu (700 AD)

Kanem-Bornu

Arguably the first major centralized state in what's now Southeast Niger/Northeast Nigeria/Mid West Chad/Northern Cameroon was the Kanem-Bornu Empire, built by the Kanuri people. Kanuri nomads eventually settled near Lake Chad at a place called Manan, founding the Duguwa dynasty.

They had a king, called the Mai, who was considered divine, supported by a council of nobles and protected by slave-soldier bodyguards. Early on, their religion revolved around animism & ancestor worship, but later they became a Muslim society by the 11th century.

After Kanem-Bornu, the next states to rise were the Hausa city-states in the 9th century AD.

9th Century AD

Northern Nigeria

Hausa City States

Honestly, we're not exactly sure when the Hausa city-states first emerged. But according to Arab traveler and geographer Al-Yaqubi in his book Kitab al-Buldan, Hausa communities were already established around 851 AD in what’s now northern Nigeria and southern Niger.

Back then, before they became Muslim, the Hausa mostly practiced animist beliefs, including spirit-possession rituals like the Bori cult.

Kanem-Bornu

By the 9th century, Kanem had expanded its influence through the integration of nomadic and pastoral communities. As Kanem expanded, they demanded taxes/tributes from subject populations.

The next polity that emerged was in southern Nigeria called Nri.

10th Century AD

Southern Nigeria:

Nri, an Igbo Polity

Around 950 AD, around southeast, an Igbo polity called Nri emerged near the Niger-Delta region.

The Igbo people lived mostly in farming societies, with a leader known as the Eze Nri who combined political, spiritual, and judicial authority. But overall, power was pretty decentralized among villages. Each Igbo village was largely autonomous, governed by councils of elders, age-based groups, and influential women's associations.

They believed in a sky lord called Chukwu—something reflected in Igbo names like Chukwunyelu ("God gave me this wonderful gift") or Chukwukelu ("God is the Creator").

At this time, the Igbo, like most African societies, didn't have a written language, relying instead on oral storytelling traditions. Only a few Sub-Saharan African states, like Alodia, Nobatia, and Makuria (Nubian Kingdoms in modern Sudan) or Aksum (in Ethiopia/Eritrea), had literate elites and merchants who used written scripts by the 10th century AD.

Northern Nigeria:

Kanem-Bornu

Around this time, Kanem was becoming more urbanized, thanks to living standards improving from the Trans-Saharan trade. They actively participated in the slave trade, relying heavily on the Tuareg—Berber traders who acted as middlemen, connecting Kanem to markets in the Abbasid Caliphate (modern-day North Africa and Middle East).

Kanem primarily traded enslaved people, ostrich feathers, and ivory. In exchange, they received horses, salt, weapons, and manufactured goods. These horses helped Kanem build strong cavalry forces, crucial for expanding territory and capturing more slaves from rival tribes.

We know these details thanks in part to the Arab historian al-Muhallabi, who wrote about Kanem’s trade activities in the 10th century AD.

Hausaland

The Hausa communities gradually developed into organized city-states. Each city-state was led by a ruler called a Sarki (king/chief), typically chosen by traditional councils. There were seven major city-states, collectively known as Hausa Bakwai ("Seven True Hausa States"): Kano, Katsina, Zaria, Daura, Biram, Rano, and Gobir.

These city-states traded textiles, leather goods, cotton, indigo dye, grain, and enslaved people, often with Tuareg traders who brought luxury goods from the north. Each city-state was centered around a fortified urban capital, and they frequently fought or allied with one another. Hausa cities would sell their goods to import salt (a food preservative) and horses.

11th Century AD

Southern Nigeria:

Ife

Alongside the Igbo Nri kingdom in the southeast, another powerful city-state emerged around this time in southwestern Nigeria: Ife.

Ife became the spiritual and cultural heartland of the Yoruba people, famous for creating exquisite bronze, brass, and terracotta sculptures, especially of royal figures.

The name of the Yoruba supreme deity was named Olodumare. Many Yoruba names reflect reverence for Olodumare, often starting with "Olu"—for example, Olumide ("My God has arrived"), Oluwaseun ("Thank God"), and Olusegun ("God is victorious").

Northern Nigeria:

Kanem-Bornu

The 11th century was a watershed moment for Kanem. Two big changes happened:

First, in the 11th Century AD, a Berber named Hummai and his Muslim faction took power, overthrowing the long-established Duguwa Dynasty. Secondly, Hummai’s new Saifawa Dynasty introduced Islam to the royal court and introduced Arabic writing in the polity. However, Islam mainly took hold among the ruling elites—the regular people mostly stuck with traditional African animist beliefs. Meanwhile, Hausaland was not yet a Muslim state.

Adopting Islam was politically smart for Kanem, connecting Kanem to the influential Fatimid Caliphate. Arab traders preferred trading with fellow Muslims, not "heathens," so embracing Islam brought legitimacy, trade, and valuable ties with scholars from places like Cairo, Tunis, and Tripoli.

Concluding Insights:

We've explored Nigeria’s immense diversity, demographic challenges, and early pre-colonial history up to roughly 1100 AD. Two points standout:

Diverse Historical Paths: By the 11th century AD, Nigeria’s major ethnic groups had distinct trajectories. In the North, the Kanuri (Kanem-Bornu) traded extensively with the Fatimid Caliphate in North Africa and adopted Arabic writing & literacy among elites following the Islamic takeover. Meanwhile, Southern groups like the Yoruba and Igbo were relatively isolated, maintaining their oral based societies. Ethnic territories extended beyond modern borders, with Hausa communities also in present-day Southern Niger, and Kanuri populations spread into North Cameroon, West Chad, South Niger, and southern Libya.

Coups & Revolts still happened in pre-colonial Africa: Even in pre-colonial Africa, we see coups and internal revolts, as seen with the Muslim takeover in Kanem-Bornu. Instability cannot be solely attributed to colonial legacy as we see it in pre-colonial Africa as well (You’ll see more in Part II!).

Next time, we'll focus on Northern Nigeria and the Trans-Saharan slave trade in Part II. We’ll continue discussing more pre-colonial Nigerian polities like Benin, Fulani, Igala, Jukun, and more.

Jeez... strong words 😅. I dont think Nigeria will ever split though. The North would be unviable without the oil in the niger-delta.

Nigeria is running a managed float not a free float. The CBN intervenes regularly and is an active participant in the FX market, often deciding what rate the FX they sell to BDC should be sold at. The last time a free float was attempted the exchange rate rose to NGN2000, basically everyone moved away from the CBNs platform and used a more organized freely accessible system (Crypto). The CBN in collaboration with NSA went after the platforms and even locked a staff of Binance hoping they could squeeze some cash. When that failed woefully, they returned to managing the float with their NAFEX. Also, the country's debt servicing has now surpassed it's revenue.