Thoughts about Corruption in Developing Countries

Does corruption need to be "solved" for a country to develop?

In grad school, during an international macro class discussion on corruption, each of us felt like we were competing to claim that our country or our parent’s country was the #1 most corrupt nation on earth.

In Ghana, I discussed how judges are bribed in land disputes. Then a Chinese immigrant mentioned corruption among provincial leaders. Then a Nigerian laughed and said everyone’s corruption is child’s play compared to Nigeria’s corruption, and tried convincing us that corruption is “entrenched in every fabric of the Nigerian way of life”. The person from Venezuela said that Chavez’s administration raided the sovereign wealth fund, the Afghan refugee said that America was funding drug dealers and pedophiles to run his country before the Taliban regained control, and a Lebanese Arab said that her country is so corrupt it has become ungovernable. Brazilians, Indians, Mexicans, Turks, Pakistanis, Egyptians, and Iranians also gave their takes on how their corruption is the worst. Back then, I didn’t realize how everyone in a non-first world country was convinced that their country was the most corrupt.

What is Corruption?

Corruption is one of those terms that isn’t well defined but “you know it when you see it”. Transparency International measures it through the “Corruption Perceptions Index”, aiming to compare corruption levels globally. Corruption manifests differently across cultures and political landscapes, encompassing bribery, nepotism, the "revolving door" phenomenon from government agencies to private board seats, and clandestine auctions of state-owned enterprises to insiders. Each form of corruption is different and each has its own implications for governance and economic development.

How do we measure Corruption and what are the Limitations of measuring it?

Transparency International (TI) is the leading organization measuring corruption, despite it’s methodological flaws. TI relies on views and survey results of “experts” or business people, not the general public.

TI aggregates data from 13 sources, including the World Bank, African Development Bank, The Economist Intelligence Unit, The Political & Economic Risk Consultancy in Hong Kong, and others to rate countries on a standardized scale of 0% to 100%. This assessment covers only government corruption. As it examines bribery, diversion of public funds, access to information to government activities, legal protection for whistleblowers, nepotistic appointments in public service, state capture by narrow vested interests, and more. However, the transparency index does NOT measure tax fraud, money laundering, informal economy activity, financial secrecy or illicit flows of money (hence my point, it captures public sector corruption, not business or private sector corruption).

Lastly, this is only looking at corruption that comes to light - via government scandals, investigations, audits, reports, or prosecutions. This means that some countries may be more corrupt than they outwardly appear, adept at concealing their misconduct.

Corruption & Economic Growth

Does corruption effect economic growth? The answer is obviously yes. If you look at the graph of all countries in the world and look at their income levels & good governance score (1 is perfect, 0 is hopelessly corrupt), you see a very good fitting exponential best-fit curve where the R^2 is 69%.

This means that approximately 69% of the variability in the average income of countries can be explained by the “level of good governance” (this means lack of corruption).

However, this does not necessarily mean that good governance directly causes higher average incomes. There may be other factors at play that contribute to this relationship.

As you can see in this graph, there are some countries like Japan where its income match the good governance best fit line. This means that Japan’s income matches right where its lack of corruption is expected to be. It’s a relatively high income country with low corruption. Meanwhile Somalia is a relatively low income country with high corruption. Any country above the best fit line has a “governance gap”, which means there’s relatively high corruption relative to their income levels. Any country below the line is governed relative well to its income. Here are some examples:

Correlation but not Causation

Less corrupt societies tend to have higher incomes, but does reducing corruption directly lead to increased wealth? This question echoes the classic mantra from high school AP Statistics: "Correlation does not imply causation."

It is my contention, that less corruption is a result of a richer society, not the cause. In the vast majority of rich countries, America, Japan, UK, South Korea, Greece, and etc. they were very corrupt on their way to becoming richer. They industrialized despite corrupt governance. It's only as these countries grew richer that their populations became less tolerant of corruption and the country had more resources to deal with corruption.

To me, this is a bitter reality. Many people from poor countries say “If we just removed the current leaders and replaced them, then the country will be better.” While there are cases of this, that’s because living standards were increasing quickly, then corruption was being reduced. Unfortunately, we are replete of cases where a strongman kills corrupt leaders while living standards are not increasing, and the new leaders become corrupt. You just replaced corrupt leaders with different faces. We have seen this country after country. When Laurent Kabila removed Mobutu, Kabila’s policies weren’t bringing growth, and Congo’s government was still corrupt. Farmers were still subsistent farmers who barely had irrigation or fertilizer. Same thing in Guinea, Central African Republic, Niger and many other countries.

What happens is corruption gets tamed faster as a country climbs out of poverty. In the year 1996, China’s good governance score a 24.3%, in 2023, now its 42%. South Korea was 38% in 1999, in 2023 now it’s 63%. Cape Verde was 49% in 2008, in 2023 its 64%. These countries are removing corruption because they focused on growth first. For South Korea and China, their growth is due (in part, but not entirely) to increasing farming yields, financial repression to give firms cheap loans, export-led growth with a cheap currency, and great execution. For Cabo Verde, it’s mainly getting richer via tourism like Seychelles and other sparsely populated island states did. Increasing farming yields and tourism revenue are low hanging fruits for developing countries that many still are not successfully executing today. For example, Mali has arable land in the South, but their ability to grow rice, wheat, & maize, is abysmal, average tones per hectare is 1.67. Even during the Vietnam war, Vietnamese average yields per hectare have never been that low.

Every Country that is Rich was Very Corrupt as it was Growing

Need examples?

Right up until the 1800s, British Ministers routinely “borrowed” from their department funds for personal profit. Britain was corrupt while it became the first industrialized country on earth, developing since the 17th century. In addition, right up until 1870, Britain would appoint high-ranking government workers on the basis of patronage (friends, family, or loyal supporters) rather than a combination of connections + merit(judging people based off results). Lastly, in the UK, the Chief Whip (a political leader who ensures that legislatures who are members of a political party vote on the party line’s legislation) used to be called the Patronage Secretary of Treasury because distributing patronage (giving favors/appointments/cash or land benefits to individuals or groups in exchange for loyalty on legislation) was the main job. Over time, the Chief Whip evolved on ensuring party discipline and enforcing the party’s voting line without cash/land patronage. Now, the UK uses more political pressure tactics through loss of pet projects for their jurisdiction and other means to enforce party lines without openly bribing politicians with cash patronage.

In America, the country was infamous for its “spoils system” where public office positions were allocated to relatives, friends, and “yes-men” of the ruling party regardless of their years of experience or credentials. This system started with Andrew Jackson in 1828, and the civil service system was not reformed until the 1880s under the Pendleton Act. In case you need a reminder, America was incredibly fast growing & industrializing during this time where by 1890, America was already the biggest economy in the world and overtook the British Empire. America is another example that was insanely corrupt when it was fast growing.

Italy, Germany, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and more were also very corrupt as they were industrializing. Even today, China has issues with corruption and is one of the fastest growing economies right now. Just do a google search on how much President Xi spends his brain space combatting corruption.

“Productive Corruption” vs. “Non- Productive Corruption”

Poor countries are rife with corrupt leaders “Papa Doc” and “Baby Doc” in Haiti, Bokassa in Central African Republic, Suharto in Indonesia, the Bongo family in Gabon, Ferdinand Marcos in The Philippines, Sani Abacha in Nigeria, Albert Fujimori in Peru, I could go on.

But there’s corruption that still moves the country forward and there’s corruption that moves the country backward/stagnation. I’ll explain.

Congo vs. Indonesian corruption

Let’s compare the Democratic Republic of Congo and Indonesia. Why? Just bear with me and you’ll see.

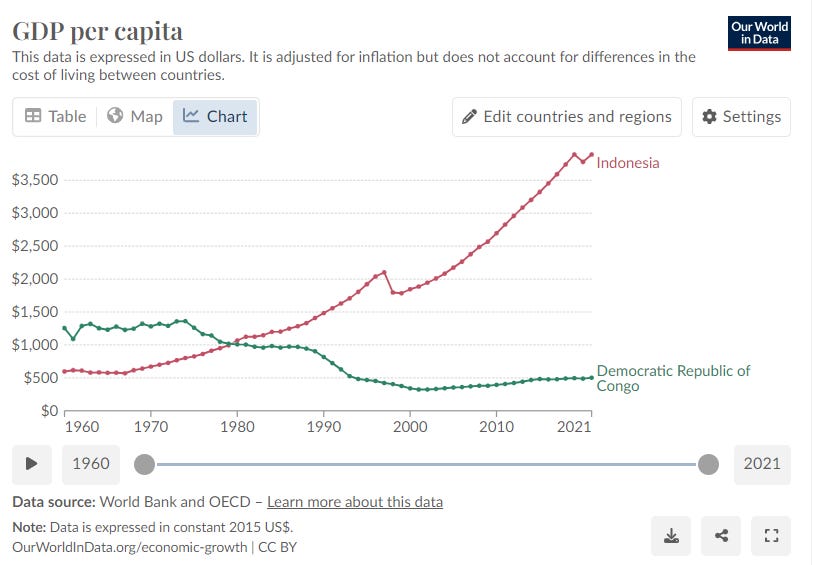

Democratic Republic of Congo, despite all of its horrific history, started off richer than Indonesia in the 1960s. In fact, the average Indonesian didn’t become richer than the average Congolese until the early 1980s. Now as of today, you can’t even put these countries on the same field. Indonesians are on average 7x richer than Congolese. Indonesia got richer while Congo got poorer. I made a two parter on Congo that you can click here (Part 1 & 2).

The countries have similarities. Indonesia, like Congo, is a bunch of different empires meshed together in a colony. Pre-Colonial Indonesia had the Majaphahit Empire, Srivijaya(Sree-vee-jah-yah), Mataram Sultanate(Mah-tah-rahm), Aceh Sultanate(Ah-chay) and a bunch of tribal societies, ethnic groups, and smaller kingdoms with their own culture, language and traditions. Then the Dutch East India Company meshed these colonies together in Indonesia. The DRC is similar, having the Kongo Kingdom, the Luba, Lunda, the Kuba, and other tribal societies, ethnic groups and smaller Kingdoms with their own culture. Both countries were colonized. The Dutch East India Company colonized and oppressed Indonesians to make coffee and sugar in the 17th century. Swahili Afro-Arabs enslaved Eastern Congolese in the 1860s, and then King Leopold “liberated the Congolese from the Arabs” only to carve out, mass murder, and colonize with his own fictional borders in the 1880s. Indonesia gained sovereignty from the Dutch in 1949 after a brutal crackdown, while the DRC achieved independence from Belgium in 1960 and had to crush rebels & Belgium funded secessionist groups, which ended in 1965. Both lands are artificial, diverse countries made up by Europeans that had to struggle for independence.

Mobutu Sese Seko ascended to power with support from the CIA and Belgium. He played a role in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba and later eliminated the successive President, Joseph Kasa-Vubu. Mobutu's reign spanned from 1965 to 1997, marked by rampant corruption. Estimates suggest he embezzled up to $5B during his 32 year role.

While Congo certainly is corrupt, the problem with the statement that “Africa’s problem is corruption” is the lack of comparative analysis to other countries. Indonesia, like I said, started off poorer. They were ruled by a socialist leaning guy named Sukarno who started off with some success but ultimately mismanaged the economy and struggled to afford rice imports. But then Suharto overthrew Sukarno in a military coup in 1966. Suharto ruled until 1998, same time period, a 32 year role. Suharto stole at maximum of $35B, making him the top kleptocrat in the 90s.

Suharto stole 7x the money of Mobutu while by 1997, made his people 12 times richer.

How did this happen? Well it depends on what you do with stolen money & bribes. Suharto’s money mostly stayed inside Indonesia, large swaths of his net worth was nationalizing firms from the Dutch, selling the state-run enterprises to his friends, and then his friends would give him “tribute payments” from foundations overseen by Suharto, called yayasans. Banks had to contribute to yayasans, and these foundations were basically Suharto’s personal piggy bank. But they money mostly stayed in the country, meaning Indonesian banks had money to lend, central bank had reserves, businesses were taking loans, and jobs were being created. In Congo, most of the money went outside the country into French villas, Swiss mansions, Belgium estates, Spanish hotels, Portuguese chateaus, Moroccan & Ivorian real estate.

In 1997, Indonesia’s central bank reserves had amassed $17.5 Billion while Congo’s central bank reserves had $98 Million.

What is done with the money?

Consider this scenario: a government official commissions an multinational construction firm to build a cathedral, inflating the project's cost. The firm submits two invoices—one reflecting the actual cost and another with an inflated amount. The difference is pocketed by the firm, while the official receives a kickback. Alternatively, kickbacks might be collected for projects like hydroelectric dams or nuclear reactors. While both scenarios involve corruption, one project is building a church while the other is providing electricity. In the Cathedral example, I am talking about Ghana, in the nuclear reactor example, I am discussing Bangladesh.

Sometimes corruption may enhance economic efficiency.

Vietnam transformed from a fully centrally planned communist economy to a more semi-capitalist “socialist market economy” in the late 1980s - The Doi Moi, following a similar pattern to China under Deng Xiaoping. But even with reforms, Vietnam used to have dozens of unnecessary red tape for someone to open a factory. It would take 6 to 12 months to prepare all the paperwork. To get something done in Vietnam, investors bribed government officials to get licenses quicker so the business person can hire workers and make more products. In an over regulated economy with too much red tape, bribery can enhance economic efficiency.

In China, bribes have also been used in the past to fast-track through regulation. This is why many times, China get projects done faster than the West. China has the world’s longest and most extensive high speed rail in the world and it was introduced in 2000s. America doesn’t have high speed rail, unless you want to technically count Acela (which only hits 240 km/h for 11% of its route). But maybe the delayed projects in California or in Nevada will be ready by 2030.

As American Political Scientist Samuel Huntington said “In terms of economic growth, the only thing worse than a society with a rigid, over-centralized dishonest bureaucracy is one with a rigid, over-centralized honest bureaucracy.” AKA, if you are overregulated, it’s better to be corrupt than to be by-the-book with onerous regulation.

In other words, corruption is bad for developing countries, but since its almost inevitable, you need to investigate if the corruption is productive or non-productive. As a country gets richer like upper-middle income or a newly industrialized economy status, then the country should spend more time reducing corruption. Also just a reminder, the vast majority of countries that industrialized/industrializing, did so while they had entrenched corruption including UK, America, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and China.

Conclusion

I wrote this article to challenge the stereotype that Africans are uniquely corrupt or that corruption is inherent to African culture. While corruption and patronage are prevalent, they are more likely a result of poverty than a cultural & genetic trait. Historical examples from countries like 18th century UK, 19th century America, early 20th century Germany, and 20th century Japan, among others, show that corruption, patronage, and bribery are not exclusive to Africa but rather common in when any country is developing.

Also, I am not saying that corruption is good, nor am I saying removing corruption isn’t necessary. All I am saying is that people who think “we can’t develop because corruption is endemic” have it backwards. You can’t remove endemic corruption, because you aren’t developed. Poverty breeds corruption as people struggle to survive and governments lack the means to enforce laws effectively.

To me this one of most psychologically unsatisfying but empirically proven things about development there is. This is an unpalatable truth about development.

The reason why rich countries are perceived to be less corrupt is because the government has more money and resources to deal with corruption. Poor countries which struggle making consistent energy, making enough food, or maintaining paved roads. If you have civil servants who don’t make much money, they will take bribes, it’s just human nature. I think people obsess over Singapore’s Lee Quan Yew’s anti-corruption efforts in his city-state in the 1960s and think that those policies can be replicated everywhere in larger nation states. Xi would love to combat corruption like Singapore did, except LQY was managing corruption in a city-state with 1.6M people in the 1960s, while Xi manages a civilization state of 1.4B people. The scale isn’t the same.

Nearly every country that is rich was corrupt when it was poor and unindustrialized. Poverty creates conditions for corruption. When people are starving or when civil servants aren’t making enough, people will take bribes.

In poor countries, its hard to collect taxes, most activity is informal, cash based, and people don’t have bank accounts. We have subsistence farmers and poorly kept shops. There’s very little tax revenue to collect from the population, and even taxing them will lead to riots. Government workers are barely making ends meet, so they need patronage to survive, and politicians need loyalty from consistencies to stay in power.

When countries grow, economic activities become more visible, farmers have surpluses, businesses have bank accounts, data collection increases, and etc. Governments can extract more revenue and pay civil service workers more. They have more money to detect and punish illegal activity.

Lastly, I think it’s really important to say that corruption is just one of the things that needs to be channeled productively as a state develops instead of “ending corruption”. Some Africans unfortunately negatively stigmatize themselves when they think only their countries are corrupt when there are many countries in Asia and Europe which can give them a run for their money on corruption. The biggest differences are whether the money stays inside the country, how overt the corruption is, or not and how corruption is being channeled.

Personally, I believe that a leader who, despite being corrupt, focuses on achievable goals like boosting tourism, making irrigation systems for farmers, or lifting farmers out of subsistence living to improve overall standards of living is preferable. This approach, exemplified by countries like Mauritius, South Korea, fosters gradual progress and eventual reduction in corruption. In contrast, a leader who resorts to violence against corrupt officials and relies solely on renegotiating contracts or nationalizing resources, without addressing underlying poverty in subsistence farming and dependence on rain-fed agriculture, perpetuates a cycle of corruption, and looting, as seen in countries like Guinea or Niger.

Sources & Books are Linked!

I expect many people to agree/disagree with me. Comment, like, share, and subscribe!

In the late 19th century US, one Tammany Hall leader drew a distinction between honest corruption and dishonest corruption. If the government issued a contract to do something, an honest corrupt operator would overcharge horribly, load the operation with friends and relatives, lean on subcontractors and so on, but the thing would be built. Dishonest corruption produced nothing. I heard this story near the Municipal Building in lower Manhattan near City Hall and the Brooklyn Bridge. That building supposedly cost $100M back in the late 19th century, maybe five to ten times what it should have cost. The much taller fifty story Woolworth Building constructed in the same era cost $13.5M, and that cost was considered horribly inflated.

Corruption was a big thing back then with a system that passed money and favors up and down the chain. There were the big guys at the top with the politicians beholden to them and the ward heelers near the bottom paying off voters and dispensing patronage. US cities were full of immigrants, so joining the corrupt systems was a big part of becoming a proper American. As you noted though, that money stayed in the US. Some of it even got circulated as part of the patronage system.

It is almost certainly correct that a wealthy state is a prerequisite to an honest one. Great article.