Book Review #1: Insights on Dambisa Moyo's Book: "Dead Aid"

A Misunderstood book. Her contention is that African Govs should be accountable to their citizens, not to Western Donors

Background on Dr. Dambisa Moyo

Dr. Dambisa Moyo is one of my favorite authors. She's a Zambian economist who studied chemistry at the University of Zambia, completed her degree and earned an MBA at American University, and later received a Master’s in Public Administration from Harvard Kennedy School and a PhD in Economics from Oxford. Dr. Moyo has worked for the World Bank advising African Countries and for Goldman Sachs researching hedge funds, debt markets, and global macro. She now sits on several boards, including Barclays, Barrick Gold, and Chevron, and is a member of the House of Lords and the Conservative Party in the UK. Her first book, Dead Aid, which I first read in October 2016 and re-read several times, inspired me to share my insights.

What are Dambisa Moyo’s biases?

From her book, I can infer that Dambisa Moyo believes in the power of markets and the private sector, viewing African socialism as a failure.

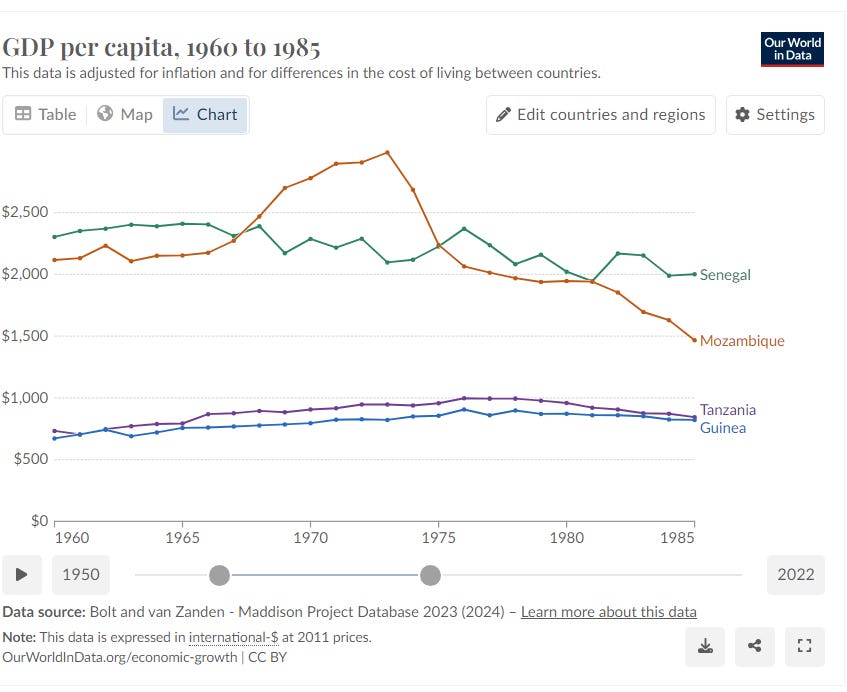

African socialism, dominant post-independence, involved government ownership of enterprises in key sectors like airlines, shipping, cement, food processing, utilities, oil & gas, railways, mining, and telecommunications, while the private sector was minimal or non-existent. Leaders such as Ahmed Touré of Guinea, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, and Modibo Keita of Mali championed this approach. However, due to failures and mismanagement, the ideology declined by the mid-1980s to early 1990s.

Most African Socialist/Communist leaders, except Rene of Seychelles, impoverished their nations or had economic stagnation. In defense Machel of Mozambique, he fought a bloody war of independence and faced a civil war, but Senghor of Senegal or Nyerere of Tanzania had no such excuse. Below you will see the poor results of the economic performance of some of the founding fathers who led their country for decades:

Her disdain for African socialism is evident when she examines Zambia's founding father, Kenneth Kaunda (Kah-oo-n-dah). Despite ruling for 27 years without wars or civil conflict, Kaunda left Zambians poorer, in real terms, than when he started governing the country. Not just in terms of income but also in terms of life expectancy. At independence, Zambians lived up to 50 years of age. When Kenneth lost elections in 1991, Zambian life expectancy decreased to 47 years of age. Below are inflation-adjusted average Zambian incomes over time, expressed in 2022 prices.

Dr. Dambisa Moyo’s Contention

The book critiques aid but is widely misunderstood. Many, including myself before reading it, thought Dr. Moyo opposed humanitarian or emergency aid. This misconception may stem from Bill Gates calling her work “promoting evil.”

Instead, Dambisa Moyo explicitly states that she is pro humanitarian aid. She is supportive of the Red Cross & Doctors Without Borders. Her contention is that official development assistance (ODA), also known as developmental aid or “foreign aid” ,given by Western Donors, UN ,World Bank, and IMF has inhibited African countries from achieving sustainable economic growth, enabled corruption, and increased rent seeking behavior.

ODA are grants or soft loans (loans with below market interest rates, generous grace periods, and longer maturities) given by richer governments to poorer governments. The biggest donors in the Organization of Economic Cooperation & Development (OECD) are the United States, European Union, United Kingdom, Japan, and Canada.

When we talk about aid here, we are talking about money thrown to African countries to help them develop. There’s bilateral aid, a government to government transfer or multilateral aid, which is the World Bank or IMF giving money to a government.

Typically, a country has domestic savings, then financial institutions use those savings as a source of funds to invest or lend to businesses, projects, customers, and governments. Then businesses invest, exporters sell abroad, customers consume, and governments spend, all driving economic growth. However, in developing countries, a lack of savings culture and prevalence of subsistence farming mean there are insufficient domestic savings. Aid thus steps in to fill this gap, with Western taxpayers providing the funds that African countries lack.

Because some forms of aid are fungible, the aid could be stolen or redirected, facilitating corruption. We are replete of examples of corruption like Congo’s President - Mobutu Sese Seko who stole a maximum of $5B and Nigeria’s Sani Abacha who stole $700M & died in a heart attack while overdosing on Viagra with Indian Prostitutes (dubbed the “Coup from Heaven” by Nigerians). Yahya Jammeh,(Jam-meh) the strongman in The Gambia, ruled for 21 years, and left his poor country worse off. Gambian incomes in 1996 averaged $640 per person or $1.80 a day. When Jammeh left office in 2017, Gambian living standards were worse… The average Gambian made $610 per person or $1.70, meanwhile Jammeh siphoned at least $50M from the state owned firms and the central bank.

Moyo is basically the opposite of her professor Jeffrey Sachs, the developer of the UN Millennium Development Goals and author of the “The End of Poverty”. Dr. Sachs believes that development aid is crucial for Africa’s development.

Instead of more developmental aid, Dr. Moyo argued that African countries should:

1. Attract foreign direct investment through legal reforms

2. Boost international and regional trade

3. Access bond markets and international lending over aid

4. Increase domestic savings via microfinance, improving agriculture for farmers, and financial literacy

5. Decrease remittance costs

$1T of Aid

Dambisa Moyo spoke about how the emergence of developmental aid came from the success of the Marshall Plan. When she wrote this book in 2009, Africa already received $1T of development assistance ($1.46 Trillion in 2024 money). To contextualize, the Marshall Plan from 1946-1951 provided $14B to Non-Communist Europe ($182 Billion in 2024 money).

Unlike Europe, Africa lacked pre-existing World class industrialized firms (Germany’s BMW & Siemens, British Rolls-Royce, French Renault, Dutch Philipps, Italian Alfa Romeo, Belgian Umicore & Solvay). Many of the entrepreneurs, operators, managers and skilled workers were still alive to remake these cars, building technologies, engines, trucks, healthcare equipment, battery chemicals, and specialty polymers. Meanwhile Africa (or all of Asia except Japan) never had these industries in 1945, making direct comparisons between African aid and European Marshal Plan impractical.

She then describes the different phases the World Bank undergone to help the developing World.

1960s: Funding large scale projects (roads, dams, railways)

1970s: Poverty reduction - education, agriculture, and healthcare.

1980s: Privatization of mismanaged state-owned enterprises, fiscal prudence, removal of price controls, and reducing fuel subsidies.

1990s: Democracy and anti-corruption

2000s: Debt relief

You can read more about this here:

The International Monetary Fund's & World Bank's Many "Attempts" to Fix Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa

In a prior article, we discussed the founding of the World Bank and IMF in anticipation of America's victory in World War Two. These institutions emerged to oversee the global economy to prevent a repeat of the protectionism that contributed to the Great Depression and, subsequently, WW2. For Part One, click here:

Dambisa Moyo’s Solution

Dambisa Moyo’s solution was that development assistance needs to be replaced with funds from capital markets - like the bond market.

How the Bond Market Works

The bond market is a debt market where governments borrow by issuing bonds. When the government can’t raise enough funds from its nationalized resource company or when taxes don’t raise enough funds, then governments issue bonds to raise funds. For example, a $1B bond with a 5% interest rate and 7-year term is like a $1B loan at 5% interest, paid back in 7 years.

The government pays $50M annually (or $25M bi-annually) and the full $1B in the seventh year. The idea is that the government uses the loan wisely, generating enough growth to pay back the bond, or issues a new bond to pay back the old one, rinse and repeat.

Dambisa Moyo argues that African countries should issue eurobonds to access international capital markets, rather than relying on development aid. By paying back loans, governments will be forced to reduce corruption, spend prudently, and demonstrate financial discipline.

Eurobonds signal a nation's creditworthiness, attracting capital flows and lowering risk profiles. As countries build a track record of loan repayment, they gain credibility, access more loans, and enjoy lower interest rates. The process involves getting a credit rating from S&P/Fitch/Moody’s, hiring a bank to represent the government, and pitching bonds to investors like pension funds, investment firms, and insurance companies.

Dambisa Moyo sees credit ratings and capital market experience as Africa's passport to global participation.

However, eurobonds pose two risks: default risk (where countries may default on interest/principal payments and face higher borrowing costs if the state returns to bond markets) and currency risk (where local currency depreciates to the dollar making dollar-denominated debts unsustainable). To mitigate these risks, countries need foreign reserves, improved trade flows, or diversified exports. If they want to borrow in local currency, they need to develop their financial institutions, allowing more complicated currency hedging instruments like currency swaps, or diversify & increase exports to make their local currencies more attractive for lenders.

The Results of Dambisa Moyo’s Solution

Written in 2009, Dambisa Moyo's book has shaped government strategies, with many countries adopting or partially adopting her solutions. Her influential advice includes boosting FDI, international & regional trade, and domestic savings, while reducing remittance costs. Key recommendations include tapping into eurobond markets, partnering with China, and minimizing reliance development aid. By 2022, most Sub-Saharan African nations had embraced parts of her guidance, with Eurobond borrowing becoming the largest source of funding in Africa.

President Paul Kagame himself praised Dambisa Moyo’s book and invited her to Rwanda’s capital, Kigali, to speak about her book the same year it was published.

Work with China

Dambisa Moyo has an entire chapter called “The Chinese are Our Friends”.

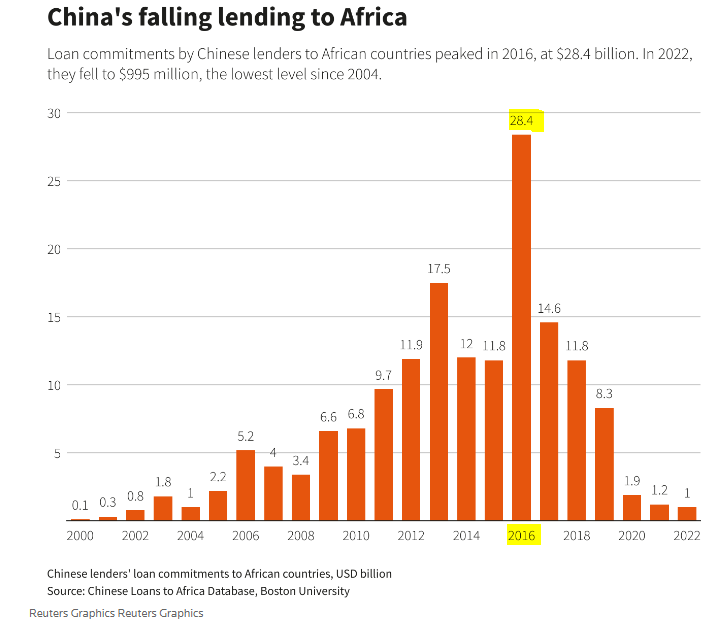

Dambisa Moyo encouraged African governments to continue borrowing from China as they build infrastructure quickly and aren’t interested in lecturing African governments about Western ideations of human rights. From 2009-2016, African governments continued to take Chinese loans. However, the lending has long peaked. In 2022, Chinese lending to Africa was slightly under $1B.

Even when we look at Chinese lending, it isn’t evenly distributed across the continent. Between 2000-2022, over half of all lending in Africa has been six countries (Angola, South Africa, Ethiopia, Sudan, Zambia, and Ghana). The other half of Chinese lending went to the remaining 48 states.

In addition, in terms of trade, Chinese trade with Africa exceeds American trade with Africa.

African countries following the Eurobond advice:

When Dambisa Moyo wrote her book, she noted that only two countries in Africa went to bond markets - Gabon and Ghana in 2007. Before that the last bond issuance was Congo-Brazzaville borrowing $600M (10 year term) in the mid 90s. During the 1990s, 35 African countries issued bonds, but between 1994 and 2007, after rounds of defaults none of them returned to the bond markets. A year after Dambisa wrote her book, 22 African countries had credit ratings in 2010, with 7 receiving investment-grade ratings (not-risky). Those countries were Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, Mauritius, Botswana, South Africa, and Namibia.

As of May 2024, 33 countries in Africa have a credit rating and have borrowed from the eurobond markets.

Where eurobonds have worked out:

The “stars” of Eurobond-utilizing African countries are Rwanda and Ivory Coast.

In 2010, Rwanda was so aid dependent that aid was equivalent 17% of Rwanda’s GDP. In 2022, aid is closer to 8.3% of Rwanda’s GDP. In 2013, Rwanda issued its first eurobond (400M loan, 6.25%, 10 year bond) which was used to finance Kigali Convention Center, RwandAir, Rwanda’s flagship state owned airlines, and the Nyabarongo hydropower project. Rwanda borrowed again in 2018, and has been exceptionally prudent. Its credit rating increased and Rwanda has the 10th highest credit rating in Africa.

In 2009, Ivory Coast’s aid was equivalent to 10% of economic output. In 2021, it decreased to 3%. Despite initial struggles with its first Eurobond in 2010 due to civil war, Ivory Coast resumed debt payments afterward. Under President Ouattara, Ivory Coast maintained fiscal prudence, leading to economic growth and an improved credit rating, reaching BB- (Ba2 by Moody's, 41% Trading Economics). This places Ivory Coast among the top four African countries by credit rating, allowing it to borrow at lower rates than nations like South Africa, Jordan, Bahrain and Costa Rica. For instance, in 2024, Ivory Coast borrowed at an average rate of 6.6%, significantly lower than Kenya's potential rate of over 10% due to its lower credit rating and risk of default. In 2010, the average Ivorian earned $1190 annually, which doubled to $2620 by 2022, surpassing countries like Laos and Ghana in income levels.

For those who think "it worked for Ivory Coast and Rwanda because they were already richer," they are incorrect.

In 2009, Rwanda was the 12th poorest Sub-Saharan African country, still recovering from genocide and the border crises from the Congo Wars. Ivory Coast, ranked 21st richest, had just come out of its first civil war and was on the brink of a second. Both were far from prosperous.

By 2022, Rwanda has improved by six spots, and Ivory Coast by 11 in Africa. Ivory Coast is now 10th in income per person in Sub-Saharan Africa. Both countries leveraged eurobonds to help their economies.

Where Eurobonds have not worked out:

Morocco, Tunisia, Namibia, and South Africa are no longer investment grade debt and Libya no longer has a credit rating.

Unfortunately, many countries have had a ratings downgrade due to increased risks since borrowing on global capital markets. In 2020, half of the African countries that had a credit rating were downgraded by at least one credit agency - S&P, Moody’s, Morningstar, and Fitch. In addition there have many several sovereign defaults.

Ghana (2022 default), Niger (2023 default due to sanctions), Mali (2022 default due to sanctions), Ethiopia (2023), Congo-Brazzaville (2016 & 2017 default), Mozambique (2017 default), and Zambia(2020 default).

Advise that has not been followed:

Some of her advice however, has obviously not been followed. Dambisa suggested eliminating all aid in 2014(5 years) or 2024 (10 years).

In terms of regional trade, there are plenty of regional trade blocks but interregional trade is low.

Africa is trying to come together with the African Continental Free Trade Area (AFCFTA) launched in January 1st 2021, but implementation has been poor.

Points of Disagreement:

Dr. Dambisa Moyo is brilliant, but like all humans she is vulnerable to biases, disagreements, and errors.

#1 Some forms of Development Aid are really good

American aid to Tanzania helped them improve their road network by financing the completion of 433 km of paved roads, reducing travel times and increasing economic activity for remote areas. The World Bank’s West African Agricultural Productivity Plan was more successful in Ghana than other West African countries. Ghana now has higher food yields than Morocco. I have a hard time believing that these projects should have been funded by 7% interest rate, 10 year eurobonds, instead of a grant or low interest rate loan with a 30 year time horizon. To me some projects, have too long a timespan to justify paying the shorter time horizon of a hedge fund.

#2 Source of corruption: Mainly aid or resources?

Her point that aid can breed corruption is valid, exemplified by Mobutu of Congo (then Zaire), who embezzled up to $5 billion. However, it's unclear whether corruption is primarily due to looting development aid or from selling natural resources to commodity traders and then raiding the state treasury or central bank for personal gain. It would have been helpful if she had specified the sources of corruption for different countries.

For instance, she cites Sani Abacha of Nigeria as an example of aid-driven corruption. However, most of Nigeria's corruption stems from a kleptocratic patronage network funded by oil exports, not aid. Similarly, many of Africa’s most corrupt leaders, such as the Bongos in Gabon, the Nguema family in Equatorial Guinea, Nguesso in Congo-Brazzaville, the dos Santos family in Angola, and Paul Biya in Cameroon, have amassed wealth primarily through oil exports. These countries do not receive significant aid relative to their GDP, since all of them are upper (Gabon, Equatorial Guinea) or lower middle income countries (Nigeria, Cameroon, Congo-Brazzaville, Angola).

#3 Correlation Causation Fallacy of “aid inhibiting growth”

In her fourth chapter, Dambisa Moyo makes stronger claims saying that aid inhibits growth, citing examples such as fostering corruption, conflict, and weakening social capital. However, her arguments lack persuasive data or graphs. Many issues attributed to aid are multi-causal, and Moyo fails to demonstrate why aid is the most significant factor.

For instance, her claim that aid chokes off the export sector by causing currency appreciation, killing export competitiveness overlooks other factors like Dutch Disease or deliberate selling of foreign currency to artificially prop up the local currency to make imports cheaper.

Moyo correlates low growth rates with high aid flows, but this oversimplifies complex economic dynamics. Low growth rates in Africa are often due to mismanaged industries, unproductive agriculture, and declining commodity prices, factors with a more significant impact than aid.

While Moyo's point about aid might hold some merit, a multifactor analysis of Africa's economic challenges would place greater emphasis on the two-decade commodity crunch from 1980-2000, poorly designed IMF structural adjustment programs, and the African Debt Crisis. She even makes some of these points in other chapters of her book.

Alternative Points of View

So far, Rwanda and Ivory Coast are the only notable successes in Dambisa Moyo's framework, though they still have progress to make.

In contrast to Moyo, Jeffrey Sachs argues that Africa needs more developmental aid and concessional lending, not eurobonds. Sachs believes that low-interest, long-term loans (30-40 year low interest loans, usually around 0.75% interest rates) are more suitable for funding schools and infrastructure, as these investments require patient capital. Many African leaders agree with Sachs; for example, Kenya has struggled with eurobonds. Recently, the Kenyan President, William Ruto, visited the United States to request more development aid and concessional financing.

Book Score:

Overall, I highly recommend the book. You will learn more about how international finance and institutions work. Go find out where you are on the spectrum between the Dambisa Moyo vs. Jeffrey Sachs debate by reading Dead Aid.

Overall both development aid and capital markets have their uses, and both have been helping. The answer is never “neoliberalism vs. state-led development” but both and finding the appropriate tools for the situation.

In 2009, when Dr. Moyo wrote the book, the break down of African country’s living standards were the following:

0 high income African countries

9 upper middle income African countries

10 lower middle income African countries

34 low income African countries

As of 2022:

1 high income African country (Seychelles)

7 upper middle income African countries

24 lower middle income African countries

22 low income African countries

African is now no longer majority low-income.

Overall, I give this book a 8.6 out of 10. Comment, ReStack, Read, & Subscribe

Edit: June 1st 2024: Corrected aid proportions in Rwanda & Ivory Coast

I loved this book. I look forward to reading more of your thoughts, Yaw. Your writing is incisive and objective. A rare find in the blinded tribalism that marks much thinking today.

Thank you very much for the excellent review and informative discussion - both in the article and your comments. I've learned a lot and am looking forward to picking up the book!