The International Monetary Fund's & World Bank's Many "Attempts" to Fix Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa

Over $2T spent but there's still ways to go

In a prior article, we discussed the founding of the World Bank and IMF in anticipation of America's victory in World War Two. These institutions emerged to oversee the global economy to prevent a repeat of the protectionism that contributed to the Great Depression and, subsequently, WW2. For Part One, click here:

The International Monetary Fund (IMF): Part 1

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is one of the financial agencies of the United Nations. There’s 190 nations that are IMF members, examples of non-members are Cuba and North Korea. Below are the biggest IMF borrowers with Argentina, Egypt, and Ukraine at the top.

Dr. Dambisa Moyo has detailed in her book “Dead Aid: Why Aid is Not Working and How There is a Better Way for Africa”, that as of 2008, Africa has received over $2T in aid. We are going to talk about how the World Bank & IMF have tried to help Africa.

In 2022, Africa’s gross economic output that year was slightly under $3T. Sub-Saharan Africa alone is $2T. From a per capita basis, your average black African makes less than $1700 a year or lives on under $5 a day. Back in 1962, black Africans were comparatively wealthier than Chinese or Indians. However, China overtook Sub-Saharan Africa in 1996, and India did so in 2016.

Why is Africa falling behind? How has the World Bank tried to fix this? Let’s tackle these questions.

After the success of the Marshall Plan, developmental aid emerged. In 1948, America transferred $13B ($163B in 2023 money) to help Western Europe recover from WW2 and to prevent communism from spreading in the nations. This included rebuilding, trade barrier removal, and more. The UK received a quarter, France a fifth, and West Germany a tenth of the aid. America also offered aid to Soviet Union and its allies, but the Eastern bloc said no. The aid primarily focused on food, fuel, and military reconstruction, allocating $3.4 billion for American commodities, $3.2 billion for food and agriculture, $1.9 billion for machinery and vehicles, and $1.6 billion for fuel.

So why has aid worked in Europe but not in Africa?

It’s mainly because Europe was already industrialized before, so it’s just restoring institutions and companies that already existed. In contrast, Africa, barring South Africa, still lacks widespread industrialization. Britain already had globally competitive, profitable aerospace firms like Hawker Siddeley in 1934 (now part of BAE Systems) and Germany already had successful car companies like BMW, which has been around since 1916. To this day Africa, doesn’t have a globally competitive, profitable automotive or aerospace firm that makes a billion dollars in revenue. Most foreign aid to Africa goes to consumption (fuel subsidies), corruption (in Swiss Banks or flats in the city of London), or unproductive projects. (Why is Ghana take a loan to build a $400M National Cathedral??)

You can focus the World Bank’s series of aid into 6 parts:

1960s: Infrastructure aid

1970s: Poverty reduction aid

1980s: Aid conditional on capitalist reforms

1990s: Aid conditional on democratic reforms

2000: Aid geared toward debt relief

2010: Inclusive Growth aid

2020: Climate Change aid

World Bank’s Infrastructure Focus on the 1960s

The 1960s was an interesting time in Africa. While it saw the attainment of independence by many nations, it was also marred by internal conflicts. Morocco declared war on Algeria, Sudan had its first civil war, Nigeria starved Igbo secessionists, Somalia declared war on Kenya and Ethiopia to annex their Somali-populated provinces, and Angola, Cabo Verde, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau were fighting their war of independence against Portugal. That’s just to start…

Many newly independent nations grappled with challenges including illiteracy, poverty, limited access to global markets, and inadequate infrastructure. This made them priority recipients for international aid

The aim of 1960s developmental aid in Africa is to fund projects that are beyond the capacity or willingness of private or public capital. Normally infrastructure and development is funded by taxpayers, government borrowing, or private banks lending their depositors’ savings. Since Africans were largely poor, subsistence farmers at independence, there was barely any income tax dollars to collect and the people didn’t have a culture of saving money in banks. In addition, the pay-offs for roads and railways were so long that it didn’t make sense for private banks to fund infrastructure. Hence, aid from wealthier nations substituted for depositors' savings or tax collections to support industrial initiatives.

During this time, World Bank and IMF’s focus was underwriting large scale industrial projects: dams, ports, bridges, irrigation systems, and etc. The idea was poor countries needed long term investments (roads, railways) and etc. These projects were not going to be funded by cash strapped banks in Africa. Examples include Kariba Dam between Zambia & Zimbabwe, the Roseires Irrigation and Soil Surveys Project in Sudan, and Hydroelectric Akosombo Volta Dam in Ghana.

These programs were financed by the World Bank’s International Development Association, their development arm that provides zero to low interest loans loans to developing countries.

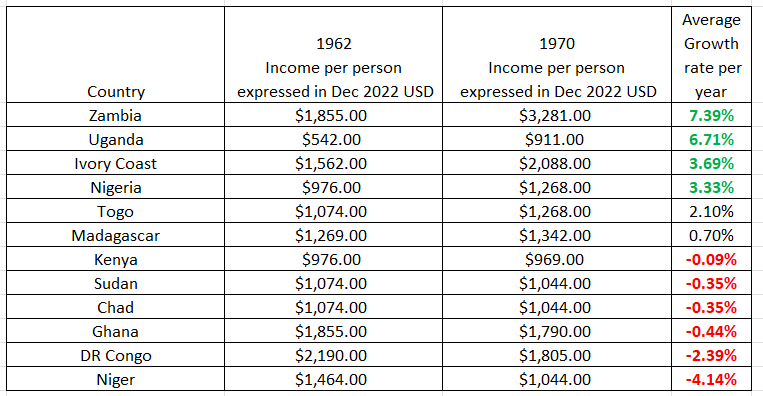

Infrastructure development bolstered African economies during the 1960s. Uganda and Ivory Coast thrived post-independence, while coup-ridden Ghana and the Democratic Republic of Congo faced challenges. Zambia was especially doing well due to a copper boom. Copper went from $.30 per pound to $.76 per pound making Zambia grow over 7% per year every year. By 1970, over $1B of aid was invested in Africa.

Here are the average growth rates in income per year for these some African countries between 1960 to 1970 adjusted for inflation in December 2022 USD. Some were growing fast and some were lackluster.

World Bank’s Poverty Reduction in the 1970s

During the 70s, two waves were happening:

1. The Nationalization wave. African governments were buying out foreign/colonial enterprises or just straight up expropriated them and indigenized (Africanized) the workforce. This included sectors like manufacturing, tourism, oil, services, finance, energy, and mining. While this move was widely supported in Africa, the second order effects were deterring foreign investment due to concerns about potential asset expropriation without fair compensation. Why would American/Japanese/European company wants to invest in Africa if the government is just going to take your assets without paying you at market prices? Foreign direct investment in Sub-Saharan Africa went from 1.5% of GDP (which is already low) to 0.1%.

The effects of less foreign investment means less technological upgrades and managerial knowhow to make competitive and state-of-the-art cars, electronics, and aerospace firms. It also meant that Africa was locked out of global supply chains. If you aren’t receiving investment, you won’t develop cluster effects of manufacturing suppliers like you see in East Asia. From the 80s and the post-Soviet Union 90s, most FDI went to China and the former communist Eastern Europe.

2. The Oil Crises: The Arab states placed an oil embargo on the West for supporting Israel in the Yom Kippur war. Then in 1979, Iran’s halt in oil production after the Iranian Revolution made prices jump again. Crude oil jumped in price from $30 a barrel to $150 a barrel in inflation adjusted prices by 1980. When oil prices rise, that means increased costs for farmers as they had to spend more on fuel, fertilizer, and transportation which all require crude oil These increased costs, lead to higher food prices. Wheat and Corn, two staple foods, had their prices double when you compare pre-post OPEC embargo. Since Africa doesn’t grow enough of its own food and imports most of it, this led to rapid inflation in Africa. Ghana had 116% inflation in 1977 and DRC had 80% inflation in the late 70s. For states that depend on crude oil and food for imports, this caused massive inflation which eroded living standards- this happened to Uganda and Zambia which were initially fast growing.

Under the new World Bank President, he focused more on poverty reduction programs. America passed its International Development and Food Assistance act for poor countries. During this decade the World Bank focused on poverty reduction thru social programs. The IDA gave $13M to Senegal to make primary schools and health centers, $6M to help Lesotho improve land soil quality for farmers, and $14M in aid to the Sahelian States (Chad, Burkina Faso, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, and Mali) to develop irrigation projects, improve rural water supply, and animal health measures after suffering from a huge drought.

Practically speaking, aid shifted from large infrastructure to rural development, water treatment, and literacy. By the end of the 1970s, social services aid increased from 10% from the 1960s to 50% by the 1970s.

Petrostates had a big win in this era - Nigeria and Sudan had amazing growth. Chad is also a petrostate, but because it was in its first civil war during this period, living standards were cratering.

Cocoa also had a huge jump in price from $530 per ton in 1970 to $1800 by 1980, helping Ivory Coast. Ghana, which was also a cocoa exporter was horrifically mismanaged in their period, with constant coups.

For the West, due to the crude oil jump in price, Western nations had to raise interest rates to tame inflation. American 10-year treasury bonds went from giving 7% in 1970 to 13% in 1980. International lenders want to gain easy returns from buying treasury bonds (effectively lending to the US government) instead of supplying money to poor countries.

In conclusion, the results were mixed for Africa in this era. See country’s growth below:

As some African regions prospered, they undertook major infrastructure projects with funding from commercial banks and the World Bank. Due to rising American interest rates on 10-year bonds (reaching 13%), African countries had to promise returns higher than 13% to attract investors. This led to African countries taking loans at floating rates exceeding 13%…

World Bank’s Focus on Free Markets in the 1980s

By 1980s, a combination of mounting debt and plummeting commodity prices triggered the emerging market debt crisis. Western economies, including America, Canada, Germany, Italy, UK, France, and Japan entered recessions from increasing up interest rates to tamp inflation from 1980-1983. If the biggest commodity buyers enter recession, then commodity demand falls & commodity prices decline, lowering government revenues for state owned commodity firms. All commodities that Africa depends on exporting had declining prices. Oil dropped from $150 per barrel in 1980 to $55 bucks by January 1990. Cocoa dropped from $4000 per ton in 1980 to $833 by January 1990. Gold dropped from $2660 per ton to $1000 per ton. These are over steep declines in prices and government revenue.

In addition, Africa still lacked irrigation systems for agriculture, as a result Africa depends on rainfall. When drought struck between 1982-1984, agricultural commodities like coffee, cocoa, tea, and sugar couldn’t be grown, leading to farmers losing their incomes.

African countries heavily rely on Western and Japanese demand for their commodities. When these economies face recession, commodity prices drop. This shrinks African government budgets, making debt interest payments difficult. Export revenues decrease while the need for food, fuel, and medicine imports increase due to population growth.

By 1980s, Latin America, Jordan, Southeast Asia, and much of Africa including Liberia (1980), Madagascar & Senegal (1981), Malawi (1982), Morocco, Nigeria, Zambia & Niger (1983), Ivory Coast, Tanzania, Mozambique, & Egypt (1984), South Africa (1985), Congo-Brazzaville, Gambia, & Gabon (1986), Angola (1988), Cameroon (1989) defaulted on their debts.

During this time, free markets was seen as the rescue package. By this point the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe had stagnate economies, West Germany was richer than East Germany, and South Korea surpassed North Korea. At this point socialist economics was fading out. Much of Africa was socialist (Ghana, Tanzania) or communist (Angola, Benin, Mozambique, Congo-Brazzaville). Even the non socialist countries like Ivory Coast, Gabon and Nigeria had many government-owned enterprises, which barely exist in America. The idea in the 1980s, was conditioning aid to these debt ridden nations was based on market based reforms. This was the era of structural adjustment programs.

Structural Adjustment Loans (SALs) are loans given to give the country life support as they undergo specific policy changes. The policies include:

1. Free floating your currency

2. Privatize government owned enterprises

3. Reducing Tariffs

4. Shrink bloated civil services

African governments started to embrace some capitalism and privatize some government owned enterprises. Government owned firms were sold off to the highest bidder, which means selling government owned assets to local businessmen or foreign investors. As an example, the Nigerian Federal Government sold off its cement firm - Benue Cement —to the business tycoon Alito Dangote in the 2000s. In many examples, the buyers of government owned enterprises, were mainly politically connected local rich Africans. This massively increased wealth and income inequality. Some investors were better an operating firms that the government and some weren’t.

The governments who took these loans did not follow the structural adjustments down to the letter. Letting the currency float led to dramatic decline in living standards. African countries didn’t have enough demand for their currencies so their exchange rates plummeted, leading to skyrocketing inflation.

Latin America and Africa both suffered in the debt crisis and underwent structural adjustment programs. By 1989, Latin America’s debt crisis ended. But Africa’s debt crisis was only half way done.

Almost every African economy had a massive decrease in living standards. Somehow Uganda did well in the 1980s and 1990s. See table below.

World Bank’s Focus on Democracy in the 1990s

Market reforms proved insufficient; African nations faced debt burdens surpassing education spending. Programs lacked customization for each country's unique context, leading to social unrest due to rising fuel and food costs.

Many African leaders were plagued by corruption Bongo of Gabon, dos Santos of Angola, Kolingba of Central African Republic, and Mobutu of Congo,

The World Bank recognized African corruption. Their new approach was to tie aid to transparent institutions, multiparty democracy, robust rule of law, and anti-corruption measures for Africa's prosperity.

In the 1990s, the world itself was transforming, after the Berlin Wall fell, Eastern Europe abandoned communism & autocracy and embraced capitalism & liberal democracy, Soviet Union collapsed, so there was no need to bankroll insane dictators. The West believed that that liberal multiparty democracy and good governance was the key to economic success.

Loans were now conditional on teaching civil service training, allowing multiparty elections, & improving government bureaucracy.

In 1991, Benin, Sierra Leone, Zambia, & Kenya allowed multiparty elections

In 1992, Ghana, Angola, Mali and Tanzania allowed multiparty democracy

In 1994, Mozambique, Malawi allowed elections

In 1999, Nigeria allowed multiparty elections.

Many other African nations suspended their one-party dictatorships and allowed elections.

Did it work? Look at the poor growth rates below. Another decade of dismal decline:

The facts are you can make good laws on paper, but implementation and a culture of abiding by those new laws is another question.

World Bank’s Focus on Debt Relief in the 2000s

Most African countries have better living standards in the early 1980s than they did in the late 90s. Activists had a new idea to reduce global poverty - massively reduce global debt.

In 1996, the IMF and World Bank launched the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative to ease debt Burdens in Africa. But it wasn’t enough. You still had activists and Pope talking about reducing global debt. The campaign was called - Jubilee 2000. Activists wanted the Group of Seven, the IMF, the African Development Bank, and World Bank to forgive all of Africa’s global debt. This allowed governments to allocate resources to social programs rather than debt payments.

The IMF put a condition on debt relief. If a country had an unsustainable debt burden, developed a track record of IMF reforms, and made a poverty reduction program got debt relief.

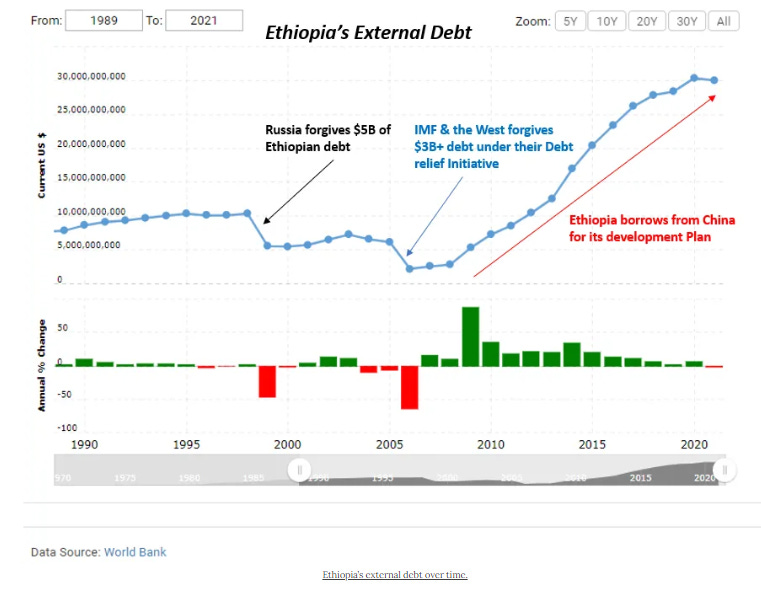

Afghanistan, Haiti, some Latin American countries, and 31 African countries including Ghana, Zambia, and Uganda received debt relief.

Debt relief came from the backs of Live 8. UK had an campaign called “Make Poverty History” and many society organizations had a movement called “Global Call to Action Against Poverty”. In 2000s, the UN created the Millennium Development Goal.

In 2005, the IMF made a multilateral debt relief initiative (MDRI). This allowed African governments to receive full debt relief from the World Bank, IMF, and African Development Bank (ADB). However, implementing this was challenging as it meant these institutions would lose their AAA+ credit rating. To facilitate this, the West had to cover the loans of the poorer nations to make it possible for the World Bank, IMF, and ADB to provide debt relief.

Most countries received their debt relief in the 2000s by the West. While that was happening, China under Hu Jintao was starting to ramp up lending to Africa.

Besides Debt relief and Chinese loans, commodity prices increased due to China’s rapid economic growth. Crude oil increased from $50 to nearly $200 per barrel. Gold, copper, and platinum had similar booms. Debt relief, higher commodity prices, unconditional Chinese lending, coupled with capitalist and democratic reforms in the 1980s and 1990s, positioned Africa for rapid growth. By 2011, people looked at this era as the “Africa Rising” period.

From 2000 to 2010, was the fastest economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa EVER. Nigeria grew at 14%, Ghana grew 11%, Ethiopia grew 8%, Kenya grew 5.6% in inflation adjusted incomes.

World Bank’s Focus on Inclusive Growth in 2010s

This was the age were the World Bank is focused on sustained shared prosperity. The World Bank focused on poverty reduction, women’s employment, and healthcare.

During this time, the China commodity boom ended around from slower growth rates post 2010 and America had the shale revolution. Lower commodity demand from China, and massive oil & gas production increase from America & Canada led to lower oil prices. Oil cratered from $130 in 2014 to $50 in 2016, killing petro-states like Nigeria, Chad, and Sudan (which lost its oil from the new nation of South Sudan). Other commodities like gold and cocoa have had relatively stable prices.

World Bank’s Focus on Climate Change Mitigation 2020

The World Bank has big plans for climate change mitigation this decade — a $200B climate action fund.

So far this decade is looking terrible for Africa unless you are Rwanda. Most African economies have had their living standards decline since COVID spread worldwide in the 2020s.

So has the world bank been effective?

In the 1960s virtually all African economies were low-income except South Africa and Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). As of 2022, Seychelles is the sole high income African country, 7 upper-middle income, 24 lower-middle income, and 22 low income countries. Considering less than half of Africa is low income, the World Bank had had some influence in that progress.

Thank you for this breakdown. This is excellent!!!

I know adding the baseline of black African social and economic indicators under colonialism to now would make this article way too long but it would show how much progress has truly been made. I do agree that showing how African countries were wealthier than some Asian countries must be included and is eye opening, I think it can be misleading. Its easy for an economy to be profitable when the labor is under terror, gun, and whip. For instance, Mississippi, the epitome of racism, poverty (consistently the poorest state in the US), and exclusion, was the richest US state in 1860 due to the number of enslaved Africans (considered property which could serve as collateral for loans) and production of cotton. But richest for who? Even now, Mississippi has the highest percentage of African Americans due to this horrific legacy. So using 1860 as a baseline to compare Mississippi to another state would be misleading. Mississippi was never industrial, just the most brutal.

I think Uganda's performance in the 80s and 90s can be explained by stability brought about by Museveni's regime after ousting the failed regime of Amin and Obote.