The Similarities and Differences in China’s Growth Strategy Compared to Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan

How China's growth model is similar and different from its Neighbors

What do China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan have in common? All transformed from agrarian economies into global powerhouses. Yet, the paths they took diverged sharply, with China rewriting the playbook by embracing foreign direct investment on its own terms. Meanwhile, Southeast Asia’s TIMP countries—Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines—struggled to replicate their success. This article unpacks the distinct strategies, missed opportunities, and critical lessons that shaped Asia's economic landscape—and what it all means for developing nations today.

Here’s the article structure:

China’s realization after Maoism

The Leapfrog Challenge: How Japan, Taiwan, & South Korea overcame it

The Three Pillars of Development: Land Reform, Financial Repression, Export Based Manufacturing

How Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia fell behind

How China’s Strategy was Similar and Different to the Asian Three

Summary

(1/6) China’s Realization After Maoism

When China emerged from its Maoist isolation period in 1979, government officials and scholars began to travel around the world to see how China stacked up.

What was their key realization?

By the late 1970s, China lagged not only behind the West but also its East Asian neighbors in economic and technological development. In terms of income per capita, China ranked below both North and Sub-Saharan African nations, underscoring the depth of China’s economic challenges.

Meanwhile Japan, along with its former colonies South Korea and Taiwan, had achieved sustained economic booms, recovering remarkably from the devastation of WWII, the Korean War, and the Taiwan Strait Crises respectively.

Japan: By 1979, Japan was the world's second-largest economy, with per capita incomes reaching 70% of US levels. This industrial prowess was reflected in global dominance: Toyota in cars, Nippon Steel in steel, Sony in electronics, and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in shipbuilding and aerospace.

South Korea: Under Park Chung-Hee, South Korea transformed from a backwards, aid-ridden farming economy into an industrial powerhouse.

Taiwan: Chiang Kai-shek’s leadership transformed Taiwan from an agrarian economy into a global hub for electronics exports.

(2/6) The Leapfrog Challenge: How Japan, Taiwan, & South Korea overcame it

Achieving "leapfrog growth"—rapid economic development that closes the gap with advanced nations—was already a monumental challenge. Japan had achieved it earlier, rising between the 1880s and 1940s to rival Western powers. Unlike other non-colonized nations such as Qing China, Ethiopia, Afghanistan, Iran, Nepal, and Thailand, which remained as poor or poorer than African or Asian colonies in the 1930s, Japan emerged as a global industrial power.

Re-industrialization in post-WWII Japan was relatively attainable since many founding entrepreneurs of major firms like Toyota, Honda, and Panasonic were still alive to rebuild and lead. In addition, selling goods to Americans during the Korean War helped Japan’s reindustrialization significantly.

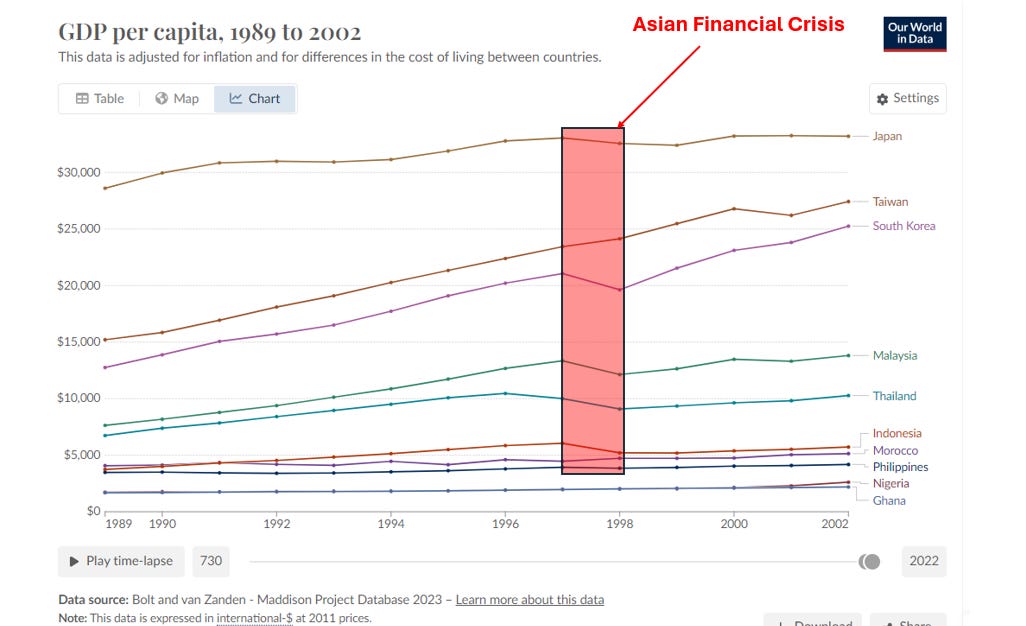

What was more remarkable was how Taiwan and South Korea—poorer than Ghana or Morocco at the 1950s—achieved rapid "catch-up growth."

(3/6) The Three Pillars of Asian Development

As outlined in Joe Studwell’s How Asia Works, the success of Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea rested on three key strategies: land reform, export-oriented manufacturing, and financial repression.

1. Agricultural Reform: "Land to the Tiller"

In all three countries, feudal landlords owned vast agricultural estates. Post-WWII governments dismantled these systems by purchasing land from landlords (paid in bonds) and redistributing it to tenant farmers.

Boosting Productivity: Smallholder farmers working for themselves were far more productive than those working for absentee landlords or collective farms.

Savings & Surpluses: Higher agricultural yields led to surpluses, which increased household savings, providing the financial foundation for industrial investment.

2. Export-oriented manufacturing

Poor countries often lag because they lack productivity-enhancing technologies available to rich countries. For example, farmers in Togo or Mozambique farm at subsistence levels. American farmers have automated tractors with advanced irrigation. To boost productivity, exports accelerate "technological catch-up" in two ways:

Foreign Currency Earnings: Exporting firms earn foreign currency (U.S. dollars) needed to buy advanced machinery and equipment.

Global Competition: Exporting forces firms to compete globally, pushing them to adopt/innovate on the latest technology, management practices, and supply chain innovations to survive. In Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, loans to firms were not primarily based on their ability to repay but rather on their export performance—a strategy known as export discipline. Firms that failed to compete in global markets faced bankruptcy or acquisition, as these governments prioritized competitive industries and businesses over protecting underperforming companies. “Survival of the Fittest” for exporting firms.

Examples:

Japan: Toyota had to rival BMW and Ford.

South Korea: Hyundai competed against Western & Japanese cars, staying relevant through reverse engineering, licensing, and eventually innovation.

Exporting also prevents inefficiencies seen in state-protected industries, which often stagnate due to lack of competition or corruption (e.g., many state-owned enterprises in Africa and Latin America). Initially, export manufacturers like Japan’s Panasonic or South Korea’s Samsung had to upgrade technology continuously through purchases, licensing agreements, reverse engineering, or outright intellectual property theft to stay competitive or gain market share. Once firms reach the global frontier (e.g., Toyota in the 1970s, Hyundai in the 1990s), growth shifts to R&D, strategic innovation, and management optimization.

Financial Repression

Financial repression involves government control over financial markets to direct loans and funds toward strategic sectors that the government thinks their firms can dominate. While effective for catch-up development, these policies often come at the expense of consumers, savers, and workers.

Key Policies and Tradeoffs:

Low Interest Rates:

Policy: Governments force banks to offer low interest rates, reducing borrowing costs for corporations and funding industrial growth.

Tradeoff: Savers faced eroded deposits due to inflation, artificially taxing individuals while subsidizing firms.

Undervalued Exchange Rates:

Policy: Central banks kept currencies artificially low by selling local currency and buying dollars on the currency market, keeping their local currency weak and their export goods artificially cheap. This boosted export competitiveness.

Tradeoff: Imports like food, fuel, and luxury goods became more expensive, burdening consumers. Its an artificial tax on importers and a subsidy for export manufacturers.

Capital Controls:

Policy: Restrictions prevented firms and individuals from moving wealth abroad, forcing profits to be reinvested domestically. Capital controls also shielded Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan from an influx of speculative short-term foreign capital, which could have fueled asset bubbles in real estate or stock markets.

Tradeoff: Wealthy individuals and firms had limited freedom to invest overseas.

Wage Suppression:

Policy: Governments ensured labor productivity grew faster than wages to keep manufacturing labor costs low. In 1960s-1980s South Korea, unions were suppressed, strikes were broken, and labor leaders were imprisoned under Park Chung-Hee’s rule. Hyundai infamously allowed no unions at all. The right to strike was illegal for some time.

Tradeoff: Workers’ wage increases were trimmed & suppressed, but export industries gained a competitive edge. Its an artificial tax on workers and a subsidy for firms.

The result of wage suppression is the graph you’ll see below, where labor productivity growth exceeded wage growth in South Korea from 1971 to 1987 for almost every year (exceptions being 1978 and 1979).

Benefits for Corporations

These government interventions gave Asian corporations “breathing room” to compete globally by offering artificially cheap loans to receive, cheap labor to employ, and cheaper goods on the world market to sell. This allowed Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan to catch up with Western industrial powers.

Contrast with Other Countries

While Japan and South Korea resisted IMF and World Bank advice to prematurely liberalize financial markets, countries like Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia followed that free-market guidance, yielding worse outcomes. Timing mattered—financial liberalization works best when markets are mature, not in their infancy. Taiwan was a special story since it was kicked out of multilateral institutions in 1971 when most of the world recognized Mainland China as the legitimate China. This gave Taiwan greater freedom to implement financial repression policies.

(4/6) Why Thailand, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia Fell Behind

According to Joe Studwell, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines (TIMP countries) lagged behind Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan for three main reasons:

1- They didn’t do genuine land reform.

Without comprehensive land reform, these countries took far longer to increase agricultural productivity. Land reform in South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan freed up resources and labor for industrial growth.

2 -The TIMP nations allowed too much FDI

This is counter-intuitive since FDI is often seen as beneficial, as seen in Singapore and Hong Kong, but two key points explain its limits. First, Singapore and Hong Kong are city-states with minimal agricultural labor, unlike most poor countries where farming dominates employment. In city-states, FDI can quickly absorb labor, but in agriculture-heavy economies, excessive FDI crowds out local industries.

Second, Singapore and Hong Kong’s reliance on FDI led to economies dominated by multinationals with no significant national manufacturing champions as seen in Japan, South Korea, or Taiwan, which restricted FDI. These countries made it unattractive for multinationals unless they transferred technology, IP, or processes through joint ventures with domestic firms or licensing, which isn’t “investor friendly”. Singapore and Hong Kong are FDI hubs centered around offshore finance & ports —an economic model that is challenging for normal countries to replicate.

In contrast, TIMP countries took a liberal FDI approach, which means their local firms didn’t get technological upgrades and the local firms had to impossibly compete with rich Western multinationals. Foreign competition killed local firms and liberal FDI laws failed to provide the technology transfer necessary for industrial upgrading, leaving their industries globally uncompetitive.

China, however, struck a balance by imposing technology transfer requirements while leveraging FDI through its special economic zones to build domestic capacity. See average FDI flows by country below, with the exception of China, less FDI means more national champions.

For TIMP countries, Thailand became a low-cost car assembly hub, while the Philippines and Malaysia focused on electronics and semiconductor packaging, with high-value activities like R&D, design, and branding jobs stayed in high income countries. Most of Indonesian foreign investment was in its natural resources, becoming dependent on oil, gas, coal, rubber, nickel and palm oil exports rather than industrial assembly. Generally speaking, unless you are Qatar or UAE have a massive amount of oil & gas with a relatively low population, being a natural resource exporter is sub-optimal. Commodity-based exports leave the nation vulnerable to international price fluctuations. When global commodity prices plunged in the 1980 & 1990s, most African countries suffered a debt crisis that persisted until the early 2000s.

You start to see the divergence by the late 80s. By 1989, Japanese people made 78% of an American. Taiwanese and South Koreans made over $12K per year, meanwhile Malaysia and Thailand were falling behind, only slightly richer than Morocco. Meanwhile, Indonesia and the Philippines were only a push ahead from African countries like Nigeria or Ghana. See graph below:

3- Premature Financial Liberalization

The TIMP countries prematurely opened their financial markets — stock, bond, currency, and real estate — to foreign capital. Instead of supporting productive long term sectors like electronics, pharmaceuticals, shipbuilding, or steel in these countries, much of the investment from Wall Street, London, Zurich, Frankfurt, Amsterdam, and Tokyo flowed to “quick buck” speculative areas like real estate, tourism, construction, and currency volatility bets. South Korea opened its financial markets in the 90s, but they weren't fully ready yet.

In 1997, the countries that opened their financial accounts too early faced the Asian Financial Crisis (Which deserves its own article).

Global investors lost confidence in Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, and South Korea, triggering capital flight. All of them tried to use their foreign reserves to defend their currency, but they nearly exhausted their foreign exchange. This lead to a currency devaluation, rampant inflation, and a wave of corporate defaults from firms that borrowed in dollar denominated debt. South Korea and the TIMP nations (except Malaysia) needed massive IMF rescue packages.

(5/6) How China was Different and Similar to the Asian Three

Similarities:

Land Reform

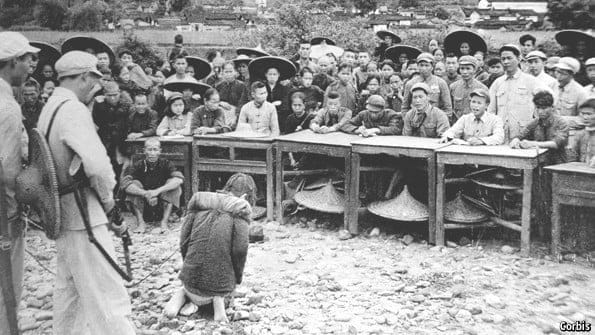

Under Mao, the party and peasants slaughtered landlords (with 1 million killed) and collectivized the land into communes. Deng Xiaoping later dismantled the communes, allowing farmers to till small plots (still state-owned) for their families and sell surplus in markets. This shift boosted yields, addressing the "free rider problem" of collectivization, where shared farming discouraged effort.

Export Manufacturing & Capital Channeling:

Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and China relied on banks and large-scale firms for export manufacturing. While South Korea, Taiwan, and China had state-owned banks, Japan's private banks followed guidance from the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), prioritizing industries like steel, ships, cars, semiconductors, and electronics.

How the Central Bank of Japan (BOJ) Kept Rates Low:

Discount Rates: Set low interest rates for banks borrowing from the BOJ, reducing borrowing costs across the economy.

Repo Market Interventions: Bought government bonds and commercial bills from banks, injecting cash (liquidity) while keeping rates low.

The Role of Commercial Bills: Private firms issued commercial bills (short-term corporate bonds) to secure funding, functioning like short-term loans with interest.

Banks’ Role: Banks purchased these bills, effectively lending to firms.

Rediscounting by the BOJ: The BOJ bought these bills from banks at a discount (e.g., paying $980K for a $1M bill). The $20K discount served as the BOJ’s fee for giving cash to the bank.

Repayment: Firms repaid the bills' full value to banks, while the BOJ earned the discount. This process gave banks immediate cash (liquidity) to issue more loans, particularly to exporters.

Focusing on Exporters: Banks prioritized purchasing bills from exporters, while the BOJ targeted rediscounting for strategic industries. This directed capital to globally competitive firms, supported by MITI's priorities. South Korea, Taiwan, and post-1980s China implemented similar credit channeling and export-driven strategies.

Export Leaders by Country:

Japan: Private Keiretsu groups.

South Korea: Private Chaebol conglomerates.

Taiwan: Political Party-Owned Enterprises.

China: Government-Owned Enterprises.

Financial Repression

Lastly, China heavily suppressed unions & wages, as seen in the graph showing labor productivity outpacing wage growth over 25 years:

China followed South Korea/Japan/Taiwan and executed policies that caused relatively low wage growth, low interest rates, and a weak currency to under cut Western competitors in exports. This effectively taxed household consumption while subsidizing their export manufacturing firms. These measures forced firms to export surplus production not absorbed by domestic markets, enabling them to compete globally. By offering cheap labor, loans, and currency, these policies provided breathing room for manufacturing firms to learn, grow, and eventually dominate international markets.

Different: China's Unique Reliance on FDI

While Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan prioritized domestic firms with strict limits on foreign investment, China made FDI a cornerstone of its strategy, enforcing technology transfer requirements to build local capacity. Even after the 80s, between 1993 and 2010, FDI accounted for 2.5%–6.5% of GDP, with inflows surging after Deng Xiaoping’s 1992 Southern Tour. Annual FDI jumped from $2 billion in the 1980s to $47 billion by 2001, largely concentrated in Special Economic Zones (SEZs) designed to attract foreign export manufacturers. See graph below:

Foreign investment helped technologically upgrade China but failed in the TIMP countries because China maintained “investor unfriendly” strict requirements for technology transfers. Multinational companies were willing to comply with tech transfer to capitalize on the immense sales potential in China.

In my opinion, blaming China alone for “stealing technology” overlooks the role of foreign companies (Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Boeing, German Cars firms, etc.) willingly transferring IP to gain market access. Their decisions were driven by the pursuit of profit, making them complicit in the process.

China's WTO entry in 2001 brought another wave of greenfield investments, with foreign firms setting up factories, offices, and supply chains. By 2010, 75% of China’s high-tech exports were produced by foreign firms, compared to domestic firms dominating exports in Japan and South Korea. Critics claimed China was "renting out its cheap labor to foreign firms," but these investments also enriched China, bringing foreign exchange and industrial expertise.

Why did a Communist Country rely so much on Foreign Multinationals?

Before trying the FDI + foreign technology transfer strategy, China initially imported factories in 1977, but this approach was limited by scarce foreign exchange and the turnkey nature of these plants. While physical equipment was obtained, critical intangibles—like supply chain management and advanced engineering techniques—were missing, leaving plants underutilized. FDI + foreign technology transfer offered a solution by bringing not just physical capital but also management expertise and operational know-how.

China probably needed tech transfer. Countries like Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea were all vassals allies of America. As a result, they benefited from technical assistance programs, educational exchanges, little restrictions to import licenses, and minimal restrictions on America’s market. Here’s some examples:

Japan’s Sony imported transistor technology licenses from the American firm Bell Labs.

South Korea’s Samsung bought integrated circuit (IC) technology licenses from the American firm Micron Technology.

Taiwan’s Industrial Technology Research Institute licensed semiconductor technology from the American firm RCA, which allowed these firms to play catch up.

China, even after it declared the Soviet Union its number one enemy after almost having a war with it, was only a frenemy of America at best.

Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan industrialized in the 1950s–1980s, when production chains were primarily national, and international trade focused on commodities or finished goods.

By the 1980s, advancements like containerization made supply chains global, shifting trade toward being mostly intermediate goods. China had great timing. China's low-cost labor, proximity to Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea, and access to world-class ports like Hong Kong positioned it perfectly as a hub for outsourced manufacturing of intermediate goods.

As a result, in purchasing power parity terms, the average Chinese is wealthier than the average African (North or Sub-Saharan) and citizens of all TIMP countries except Malaysia.

(6/6) Summary:

Land reform, export manufacturing, limited FDI, and financial repression propelled Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea to rapid development.

In contrast, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Malaysia suffered from slower growth due to a lack of land reform, excessively liberal FDI rules stifling domestic champions, and premature financial liberalization.

Post 1980 China adopted key elements of the East Asian model while embracing FDI with strict technology transfer requirements. American, European, and Japanese firms, eager to access China's massive market, willingly shared IP with local Chinese firms.

China also seized the opportunity presented by advancements in transportation and globalization, leveraging its unique timing, geography, and exceptional execution capabilities. However, replicating China's path is unlikely for most developing countries due to these distinct advantages.

In a future article, I’ll explore what African countries can and cannot learn from East Asia's development strategies.

I'm really looking forward to your take on how applicable this is to African countries, in either direction.

When I read and reviewed Studwell's book, I did some research and ultimately concluded that the Studwell "Success Sequence" you elucidate was probably contingent on the time period and specific countries rather than a universal formula.

The three countries that have become "developed" since then (Ireland, Israel, Chile) didn't follow that path.

Ireland - being part of the EU and aggressively targeting multinational corporate FDI and headquarters location via favorable tax minimization laws. The “double Irish” and such.

Israel - a highly educated base population supplemented by highly skilled immigration, targeting high tech, military hardware, and software, with substantial FDI.

Chile - Pinochet basically pulled a mini Lee Kuan Yew after becoming dictator, outsourcing his economic decisions to The Chicago Boys, who put the economy on privatized and liberalized economic footing while pivoting to an export focus. Notably however, they didn’t focus on manufacturing or industrialization - the biggest exports are copper, wine, fruit, and fish.

None of them followed the Success Sequence. And sure, his book is "How Asia Works" not how the rest of the world works. But let's look at Malaysia and Vietnam:

Malaysia ($12k per capita GDP as of 2023) is right on the edge of being considered developed (a country is considered “developed” if it has a per-capita-GDP of between $12-$15k and has decent qualitative measures on health, education, and infrastructure), and it's actually SE Asian and didn't follow the success sequence - it never did extensive land reform, it has pushed on manufacturing, but 20% of exports and government revenue is oil and gas, and 23% of employment is tourism based. Malaysia was one of his “failure” cases in the book in terms of not doing land reform at all, and in terms of doing manufacturing wrong, but here they are.

Or how about Vietnam? It’s been explicitly and assiduously following the Studwell success sequence since 1986. Exports are nearly 90% of the economy, and manufacturing has steadily grown in that time to be more than 25% of GDP. But in that nearly 40 years, it’s gone from roughly $700 GDP per capita to roughly $4,500 GDP per capita, a factor of roughly 6 improvement, whereas in their comparable periods of growth, Taiwan’s and Korea’s improved about 60x, and China and Ireland at least 12x (Vietnam’s growth is in line with historic Japanese and Israeli growth rates, which both started at a *much* higher baseline GDP per capita). If they can maintain this pace (and that's not a given, growth usually slows down the larger your baseline GDP gets), they might make “developed” status by around 2040, roughly 60 years after starting - but everyone else hit it after 20-40 years.

For another thing, "land reform" isn't going to do much now, when agriculture is a tiny part (5-15%) of even the "failure" economies in his book like Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Philippines:

https://imgur.com/a/xnGvS0e

So overall I don't think it's a universally applicable formula. Definitely interested in your follow up take re African countries.

I do wonder what effect these wage suppression policies have had on wealth inequality in China vs the trio vs the TIMP countries. In comparison, was the flexibility of the American and select European governments towards unions and antitrust, post-1945 simply because they had a 60-year head start in industrialization, or because they factored in broader questions about internal political power (because their leftist/socdem parties were stronger)? I think with the Lib Dems’ underperformance, President Yoon’s political crisis, the KMT’s fall relative to the DPP, and Western pressure on the CCP, the four East Asian giants will have to start adopting consumption- and equality-first class politics into their economic strategies sooner rather than later.