How Global Commodity Traders Leverage Developing Countries' Resources to Make Money

Let's use Jamaica as a Case Study

A French commodity trader once remarked, “It’s almost unfair competition. In most companies, if you asked to lend money to Jamaica, they’d throw you out the window”. This sentiment highlights the unique edge commodity traders have when extending credit to risky countries like Jamaica.

You are probably asking: “What is the commodity trader getting in return for lending to such a risky country?”

The answer: discounts on resources

Commodity traders can make a killing by buying resources from a cash strapped country at a fraction of the international price (because the trader has the negotiating power), and then sell those resources on the spot market (the market where commodities are traded for immediate delivery) for the full value.

Don’t know these companies? They entail firms like Glencore, Trafigura, and Vitol.

Hyper Quick Overview of Jamaica

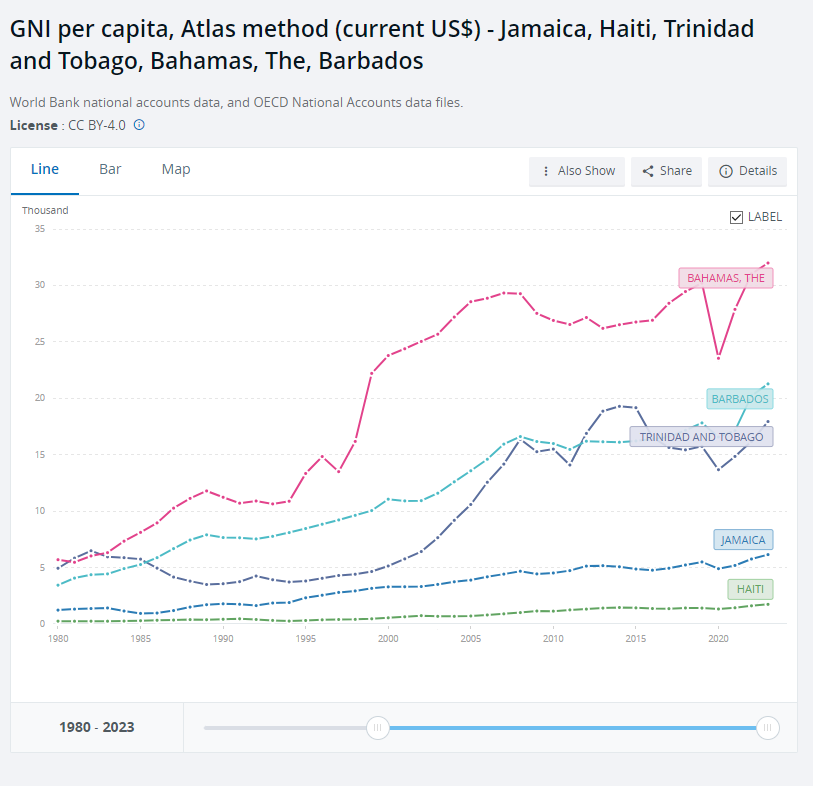

Jamaica received independence from Britain in 1962. Today, Jamaica is the third poorest Caribbean country (beating only Haiti and Suriname), with a long way to go to catch up to places like Bahamas or Barbados. It ranks #2 on the Human Flight & Brain Drain Index.

Yet if I compare it to African countries by just looking at income numbers and exclude crime in bad areas, Jamaica looks decent. I’ve been there myself and I had a fantastic time in Montego Bay.

Jamaica has around ~3M people. African countries with similar population sizes would include Eritrea, Gambia, Botswana, Namibia, Gabon, Lesotho, and Guinea-Bissau. Jamaicans are richer than every Sub-Saharan African country, on average, except South Africans, Batswana, Gabonese, Mauritians, and Seychellois.

The average Jamaican earns $6150 a year at market exchange rates and $11,000 a year at purchasing power party, placing Jamaica as an “upper middle income country” (Note: The World Bank cutoff for upper middle income is a nation’s average annual income that exceeds $4516, but less than $14,005 for the 2023 year).

Jamaica’s top foreign exchange earner is travel & tourism, bringing in $2.1B in 2021, on par with South Africa.

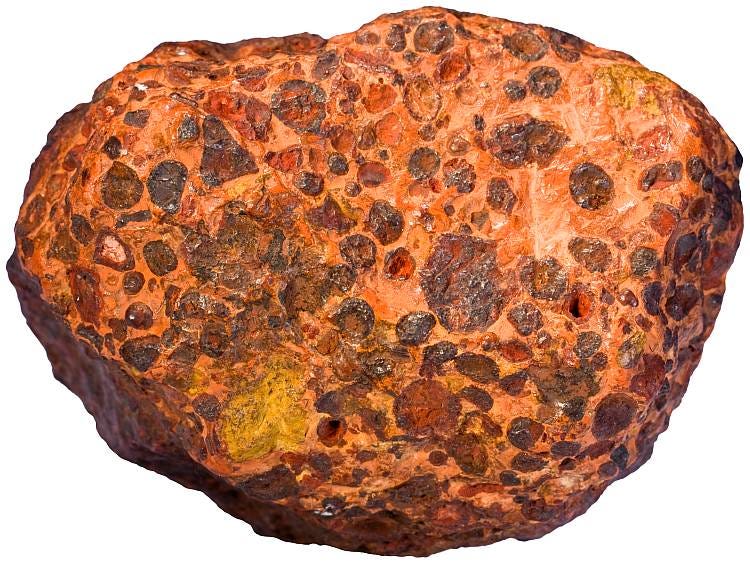

But Jamaica isn’t just a tourist destination; it’s rich in bauxite, a key ingredient in aluminum production.

Jamaica ranks 5th globally in bauxite reserves, 7th in production, 7th in aluminum ore exports, and 14th in aluminum oxide exports. The bauxite is transformed into alumina, and then alumina needs to be transformed into aluminum metal, which has many use cases in aerospace, hardware, and etc.

Bauxite mining happened late in Jamaican colonialism, around the early 1950s. Before mining, Jamaica was a sugar plantation slave colony. But in 1952, Jamaica’s first bauxite was shipped and by 1957, Jamaica was the leading bauxite producer for a while. Australia overtook Jamaica in 1971, by late 1970s, Guinea beat Jamaica, and then Brazil in the 1980s, and China and India overtook Jamaica in the 2000s.

Resource Nationalism

In many developing countries in the 1950s-1980s, a popular socialist trend emerged called 'resource nationalism.' The idea was simple: governments would take control of mining and oil firms from foreign companies to ensure the “resources benefited the people rather than foreign profit seekers”. Some governments used resource nationalism as an excuse to steal as I mentioned in Angola, Congo-Brazzaville, Gabon, and others.

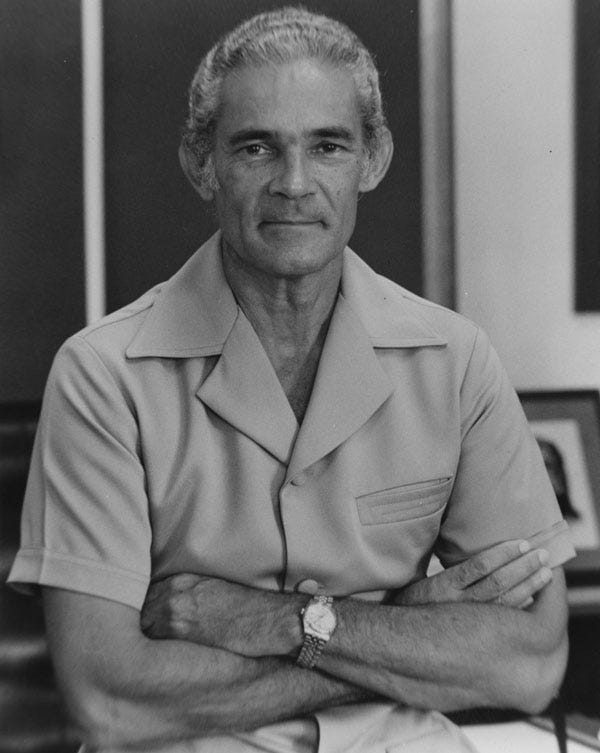

In resource nationalism, this could mean buying minority (under 50%) , majority stakes, outright purchasing entire companies, or even seizing assets and negotiating payments later. In Jamaica, Prime Minister Michael Manley pursued resource nationalism over bauxite and alumina.

Manley’s government acquired a 51% stake in the bauxite industry & alumina refineries, previously controlled by American companies like Kaiser Aluminum & Alcoa, as well as Canadian Alcan. He also bought back the bauxite reserve lands and granted the companies mining leases instead. By 1974, he had raised bauxite taxes, and, by 1976, he audited and inspected the industry.

The nationalized bauxite and alumina refineries, operated by Clarendon Alumina Production (CAP) (later known as Jamalco), allowed Jamaica to capture more of the value-added processing of bauxite into alumina rather than just exporting raw bauxite.

But “owning the resources” is only a quarter of the battle. Without expertise in selling on commodity markets or managing timely shipments, ownership alone doesn’t translate into success. That’s where commodity firms stepped in. But before we dive into their role, let’s look at the challenges Jamaica was facing during this time.

Crisis in the 1970s!

As Jamaica was claiming its resources, another big macro event happened.

In the 1970s, Jamaica—like much of the world outside the Gulf States—was hit hard by the oil crises. The 1973 OPEC production cuts (oil went from $30 per barrel to $67 per barrel in 2024 prices), and the 1979 Iranian Revolution which halted oil production (oil went from $70 per barrel to $150 per barrel in 2024 prices). Both of these events caused global oil prices to soar. Look at the chart below to look at oil prices from 1970 to 1980. They are inflation adjusted in 2024 prices:

The oil crises caused Jamaica and much of the developing world to run massive current account deficits (importing more than exporting), and Jamaica was borrowing to make up the difference. The country teetered on the brink of bankruptcy multiple times, exacerbated by gangs, drugs, and violence. In fact, Bob Marley was almost assassinated in December 1976. As the American ambassador to Jamaica grimly noted, he was “tired of walking over dead bodies” in Jamaica.

The Dark 1980s

Borrow From Trading shops just to have Gas

Jamaica faced severe economic challenges in the 1980s, largely due to the high cost of oil imports. The country had already received multiple IMF bailouts and was in the middle of a 4th IMF loan. Once again, foreign exchange reserves were running low. Hugh Hart, the minister for mining and energy, received a dire message from the central bank: Jamaica didn’t have enough U.S. dollars to purchase a vital cargo of oil. With fuel supplies set to run out in two days, the risk of riots in an already unstable country loomed large.

At that time, Jamaica typically bought 300,000 barrels of oil, refining it in Kingston. The Central Bank would usually guarantee $10 million to cover the cost. But with no money left, Jamaica couldn’t buy oil, meaning no gasoline or diesel could be produced, and gas stations would be forced to close.

The government of Jamaica could do a couple things.

A) They can borrow from international markets to get $10M. Unfortunately they could not do that since Jamaica was seen as an economic basket case by investors, so it was locked out of financial markets.

B) They can go to the IMF for another loan. However, Jamaica just borrowed an IMF loan, and hates their austerity policies and monitoring.

C) Secure a line of credit from commodity traders.

Mr. Hart called commodity traders from Switzerland, to reach the firm Marc Rich & Co. The commodity traders brought 300K crude oil from Venezuela to Jamaica. The financial arrangements were kept off the books, appearing as assets rather than debt to meet IMF requirements.

In another situation, Jamaica needed commodity traders help when it came to nationalizing aluminum.

Borrowing for Bailouts

The Jamaican aluminum industry struggled in the 1980s. The American firm Reynolds closed its operations in 1984. Alcoa closed down a plant as well.

Also in the 1980s, America & Western Europe were in recessions and Japan had slow growth in the early 1980s, curbing global demand, and new bauxite production from Guinea and Brazil increased global supply, cratering prices.

To save the industry, Hugh Hart, minister of mining and energy, sought to nationalize the entire alumina sector but lacked the funds. He needed someone to buy the alumina in advance, and then the government could use the cash proceeds to nationalize dying plants from Alcoa & Reynolds. But the issue was, alumina prices were cratering in the 1980s. In addition, alumina can’t be stored for long since it absorbs moisture in the air.

The Jamaican government entered a 10-year contract with the commodity traders, Marc Rich & Co, for the country’s alumina (the intermediary product between bauxite and aluminum), at a rate 25% below typical contract terms. .

By buying alumina at a discount and selling it at the spot market price, Marc Rich made a killing. Glencore, the successor of Marc Rich & Co, did a similar deal decades later, and made $370M from Jamaica alone in two years.

A similar arrangement happened when the Jamaican government wanted to buy the country’s oil refinery from an Exxon subsidiary. Commodity traders lent the necessary funds, and they even financed Jamaica’s Olympic team in 1984.

Over 30 years, commodity firms provided Jamaica with over $1 billion in financing. In comparison, Jamaica has borrowed over $2B from the IMF in total. While the traders couldn’t meet all of Jamaica’s financial needs, they played a crucial role in keeping the country afloat.

Concluding Thoughts

When a developing country anchors its currency but constantly imports more than it exports, it's only a matter of time before reserves run dry. When that happens, the country can't afford to import essentials like food or fuel.

There’s nothing worse than being a stagnant developing economy that depends on the world more than the world depends on it (hence the country imports more than it exports). Traditional lenders shy away, leaving you with two options: turn to the IMF, which will push for a floating currency (causing devaluation, inflation, and unrest), or approach a shady commodity trader like Marc Rich & Co (now Glencore), who profits from your desperation.

This scenario plays out around the globe. But ultimately, for this to end the country must get back on track to having a stable monetary policy. The world won't bend its rules for struggling nations—the basic law of money remains: if you run out of cash, you need help. To break free from this cycle, countries must develop within their constraints, like China and Vietnam. Unfortunately not every developing country moves at the same pace.

China took just two IMF loans before 1987 and then never looked back, it doesn’t even need the IMF, it has built up $3 trillion in reserves. India stopped borrowing after its seventh loan in 1993. Meanwhile, Jamaica has taken 16 IMF loans, Senegal 19. Hopefully, more countries can break this pattern and no longer rely on the IMF or commodity traders.

I didn't dive deep into Jamaica's economic history here, but it's worth noting that Jamaica has had socialist oriented leaders like Michael and neoliberal oriented leaders like Edward Seaga. Despite efforts like creating special economic zones in the '70s and '80s, Jamaica's goods exports have remained stagnant, Jamaica exported slightly less than $2 billion in 1995, and it continues to export slightly less than $2 billion goods in 2022. In the future, I'll explore the successes and failures of these zones in more detail.

Note:

Thank you to subscribers who filled out the audience insights article.

The typical respondent to my poll is a 25-34-year-old male living in a coastal city in the United States, earning between $100K and $200K, and holding at least a bachelor’s degree. Politically, they tend to be center-left, supporting a liberal, social democratic/capitalist system with a robust welfare state, and they have a pro-Western outlook. It's fascinating to see this profile, and I hope my audience becomes more diverse over time!

Surprised to see so many upper middle class Americans be interested Africa's economic situation. Perhaps that's the general demographic for Substack.

Highly recommend The World for Sale by by Javier Blas and Jack Farchy (reviewed in one of the links up top). It's highly informative.