The Economic & Geopolitical History of Congo-Brazzaville

The More Successful, Equally Corrupt, and Lesser-Known Congo

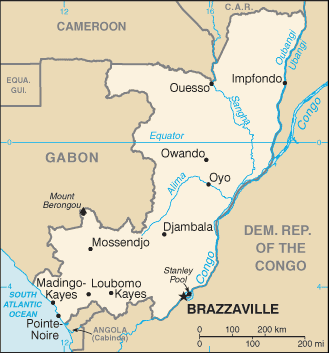

Congo-Brazzaville, or Republic of Congo (distinct from the more conflict ridden and infamous, Democratic Republic of Congo) is a petrostate in Central West Africa with a population of 6.2M as of 2024. Similar to its neighbor Gabon, its sparsely populated since the vast majority of the country is jungle. As a result, as of 2022, Congo-Brazzaville is the 5th most urbanized country in Africa and it is a lower-middle income country, with major urban centers including Brazzaville, Point Noire, or Dolisie. The country is the same size as NY, NJ, and the New England states combined. The capital, Brazzaville, was named after French explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza, who negotiated treaties with local chiefs to create the polity.

The country has many tribes like Kongo, Sangha, Teke, etc.

Besides crude oil, Congo-Brazzaville also sells billions of copper. However, large portions of this copper is siphoned/mislabeled from the other Congo. Most of Congo-Brazzaville’s oil is sold to China and its copper is mainly sold to UAE.

Oil serves as Congo-Brazzaville's primary foreign currency and main source of government revenue. However, the country faces notable bribery and corruption issues, particularly with European oil firms like Total and Eni.

While Congo-Brazzaville's oil sales are significant, they pale in comparison to countries like Saudi Arabia & UAE. In 2022, Saudi Arabia sold $236 billion worth of oil, the UAE sold $105 billion, while Congo-Brazzaville sold $8.2 billion. Considering their population’s (36M, 9.4M, and 6M) respectively, if we had to think of how much oil is being sold relative to population (oil exports per capita) then, Saudi Arabia generates ~$6500 per person, the UAE ~$11,000, and Congo-Brazzaville only ~$1400, highlighting the disparity in how much “bang for its buck” each nation receives from oil exports.

Moreover, Congo-Brazzaville has lower oil reserves compared to these countries. As of 2021, Saudi Arabia ranks 2nd globally with 259 billion barrels, the UAE 7th with 98 billion barrels, and Congo-Brazzaville 32nd with 2.9 billion barrels, less than countries like Egypt, Yemen, or Ecuador.

Throughout much of its history, Congo-Brazzaville has experienced current account deficits, indicating it bought more goods than it sold in oil abroad. It only began running surpluses in the early 2000s during the oil boom.

In addition, Congo-Brazzaville lacks a Sovereign Wealth Fund, unlike the Gulf States. Saudi Arabia’s Fund has has $925B in assets, while UAE’s funds exceed $1 Trillion (Abu Dhabi: $993B, Dubai: $340B, Mubadala: $139B, the Emirates Investment Authority: $87B, etc.)

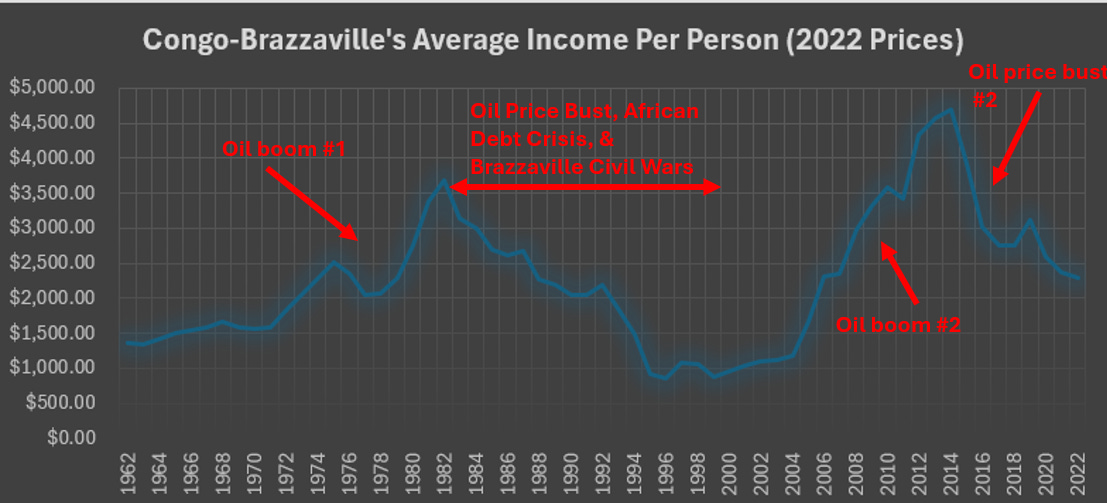

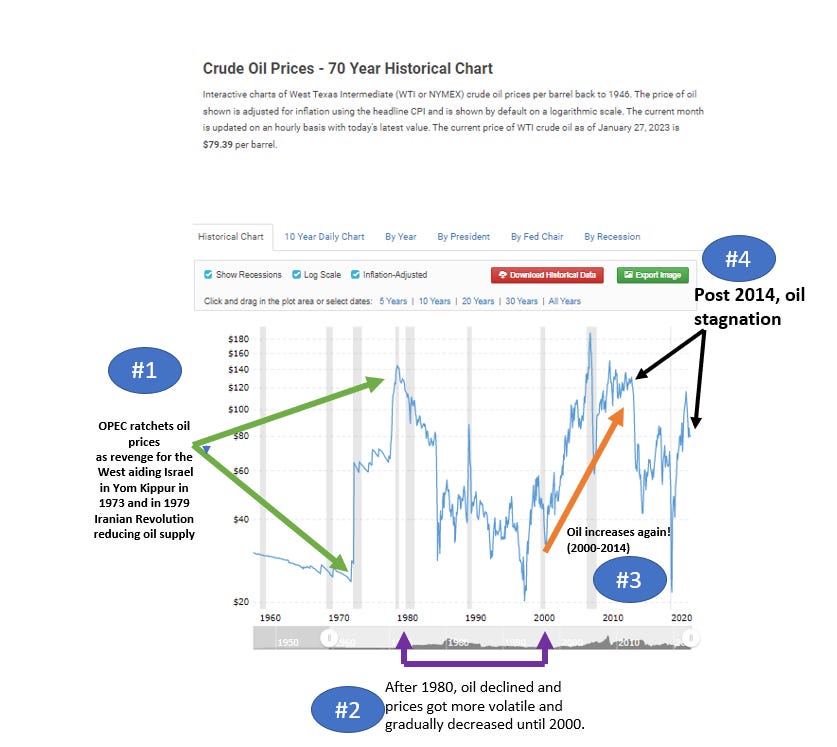

Due to its smaller oil reserves and the absence of a Sovereign Wealth Fund cushion, Congo-Brazzaville suffers from the boom-bust cycle of oil prices. The oil dependence for government revenue has led to a rent seeking culture fostering a bloated civil service, political patronage, and corruption. Look below to see the oil price fluctuation:

As you can see, oil prices went up from 1973-1981 thanks to events like OPEC's embargo post-Yom Kippur War, the Iranian Revolution, and the start of the Iraq-Iran War in 1980.

By 1981, an oil glut emerged amid recessions in the West and Japan, coupled with increased production from non-OPEC producers from Brazil & Malaysia. Also, Saudi Arabia's full-capacity production in 1985 led to a massive surplus and a subsequent price crash that lasted until the late 90s.

China's rapid economic growth from the late 90s drove oil price increases until 2014, but imports decreased & stagnated post-2015. Additionally, the American shale revolution boosted production, contributing to plummeting oil prices, exacerbated by COVID-19's demand destruction from 2015-2022.

Congo-Brazzaville's economic growth & decline closely mirrors oil price fluctuations, evident in its average incomes chart:

Pre-Colonial History

Bantu Africans have been in this region since 1000 BC.

Kongo Kingdoms (1390-1914)

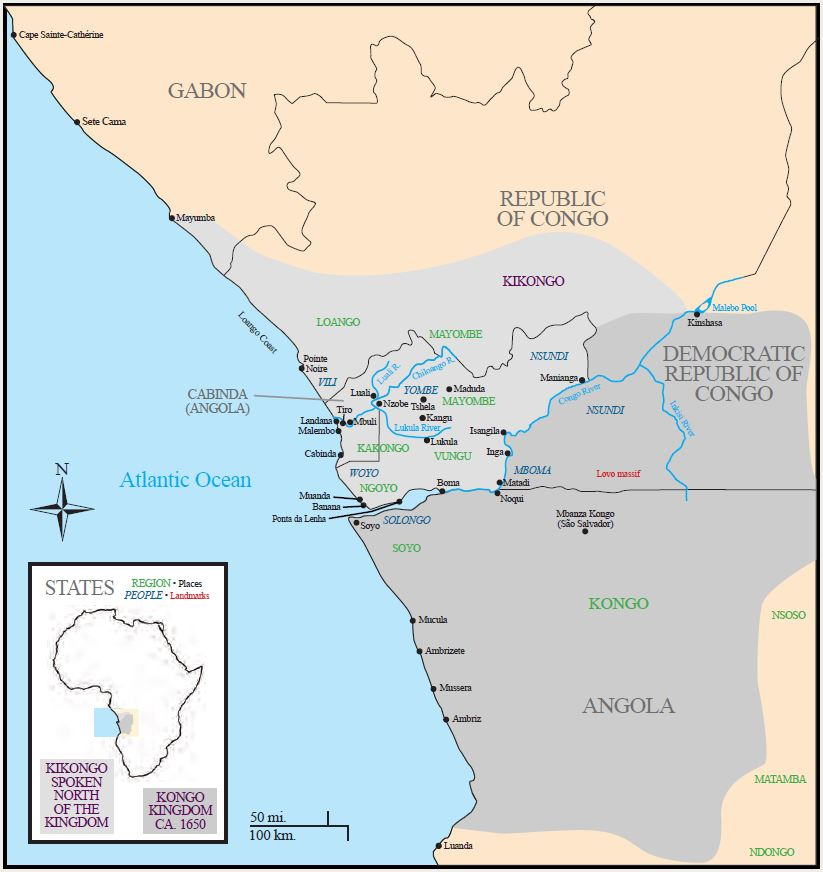

I first wrote about Kongo in my Democratic Republic of Congo & Sao Tome articles, but I’ll summarize. The Kongo Kingdom, spanning the coasts of modern-day Angola, Gabon, and the two Congos, was a pre-industrial society with a powerful king and a population of aristocrats, farmers, hunters, and fishermen.

Portugal established relations with Kongo in 1483, impressed by its sophistication, but still maintaining technological superiority. Portugal offered guidance on governance, trade development, and education, with Kongolese traveling to Portugal and even Rome. In exchange, Kongo traded slaves and iron.

Initially recognized as a sovereign nation, Kongo was gradually vassalized by Portugal, which blocked Kongo's embassy to the Vatican and captured French ships attempting to trade with Kongo.

By the late 1500s, Portugal disregarded Kongo's sovereignty, fueling the slave trade by paying tribal chiefs in guns and food to kidnap people, depopulating areas of Kongo. Kongo Kings attempted to reassert control and allied with the Dutch to destroy Portuguese Angola, but ultimately failed to stop Portugal's exploitation.

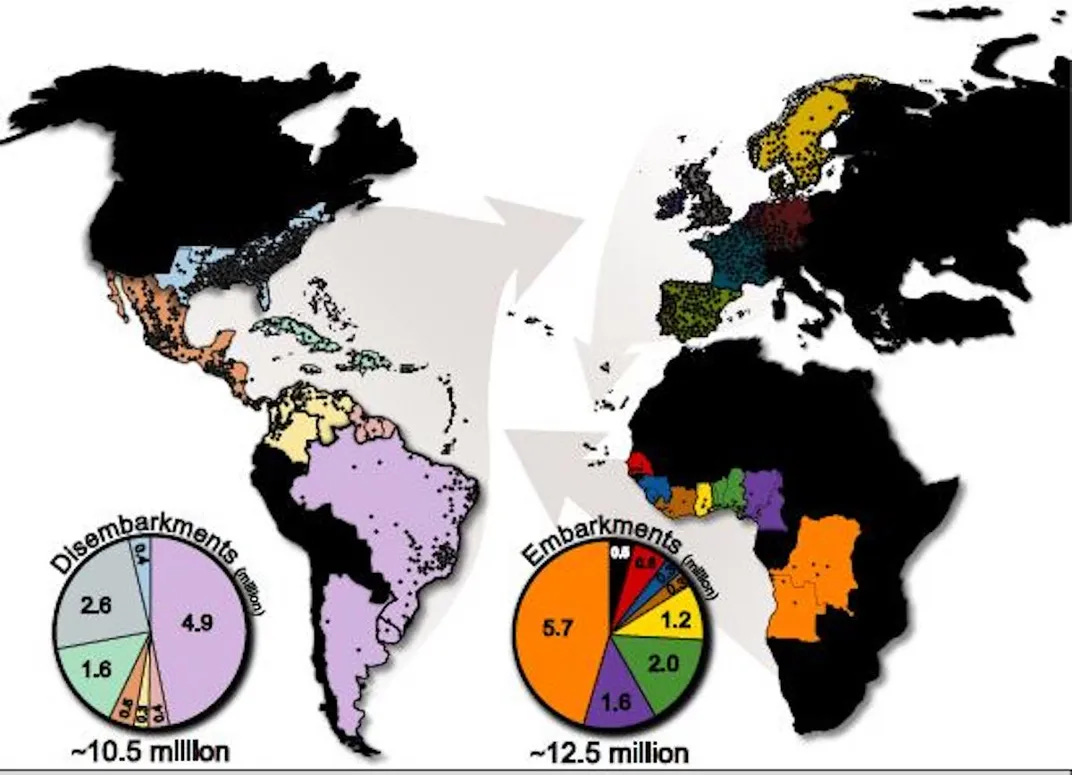

45% of slaves of from the Transatlantic slave trade came from the coasts of Kongo. They live in Brazil now.

As the Kongo Kingdom declined, it fragmented into smaller entities. Local chiefs broke away, and the region devolved into village clusters, forest principalities, and weaker kingdoms like Loango and Tio/ Teke.

French Middle Congo (1891-1960)

Portugal claimed sovereignty over Kongo, but France did not respect Portugal’s claim. French agents persuaded tribal chiefs to sign treaties that they could not read in return for food, guns, and textiles. This led to the fragmentation of Kongo, merged with other territories to form French Middle Congo (Congo-Brazzaville), Portuguese Congo (Angola and Cabinda enclave), and King Leopold's Congo (Democratic Republic of Congo).

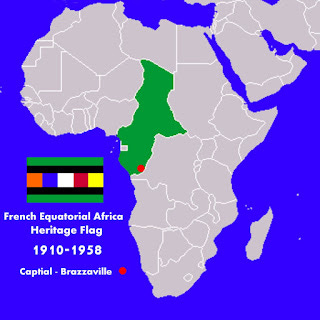

Brazzaville was made the capital of French Equatorial Africa.

France compelled Congolese to produce various goods like timber (their main export), palm oil, ivory, rubber, peanuts, and coffee and forced them to construct infrastructure like roads and ports for transportation. Payment often consisted of torn clothes and beads. French state-owned enterprises in Congo-Brazzaville oversaw the collection of these resources from forced laborers across French Equatorial Africa.

In 1928, 17,000 Africans died building the Congo-Ocean railway, connecting the Coastal city, Port-Noire to the capital Brazzaville, due to malaria and poor working conditions.

As a reward for African loyalty in WWII, France treated their colonies better: ending forced labor, increasing investment, and boosting African representation in the French Parliament. By 1957, it became the 6th richest African colony, exceeding the newly independent Tunisia. See incomes below:

Also, French Total discovered offshore oil in Congo-Brazzaville in 1957. However, oil extraction didn't begin until 1972, following independence.

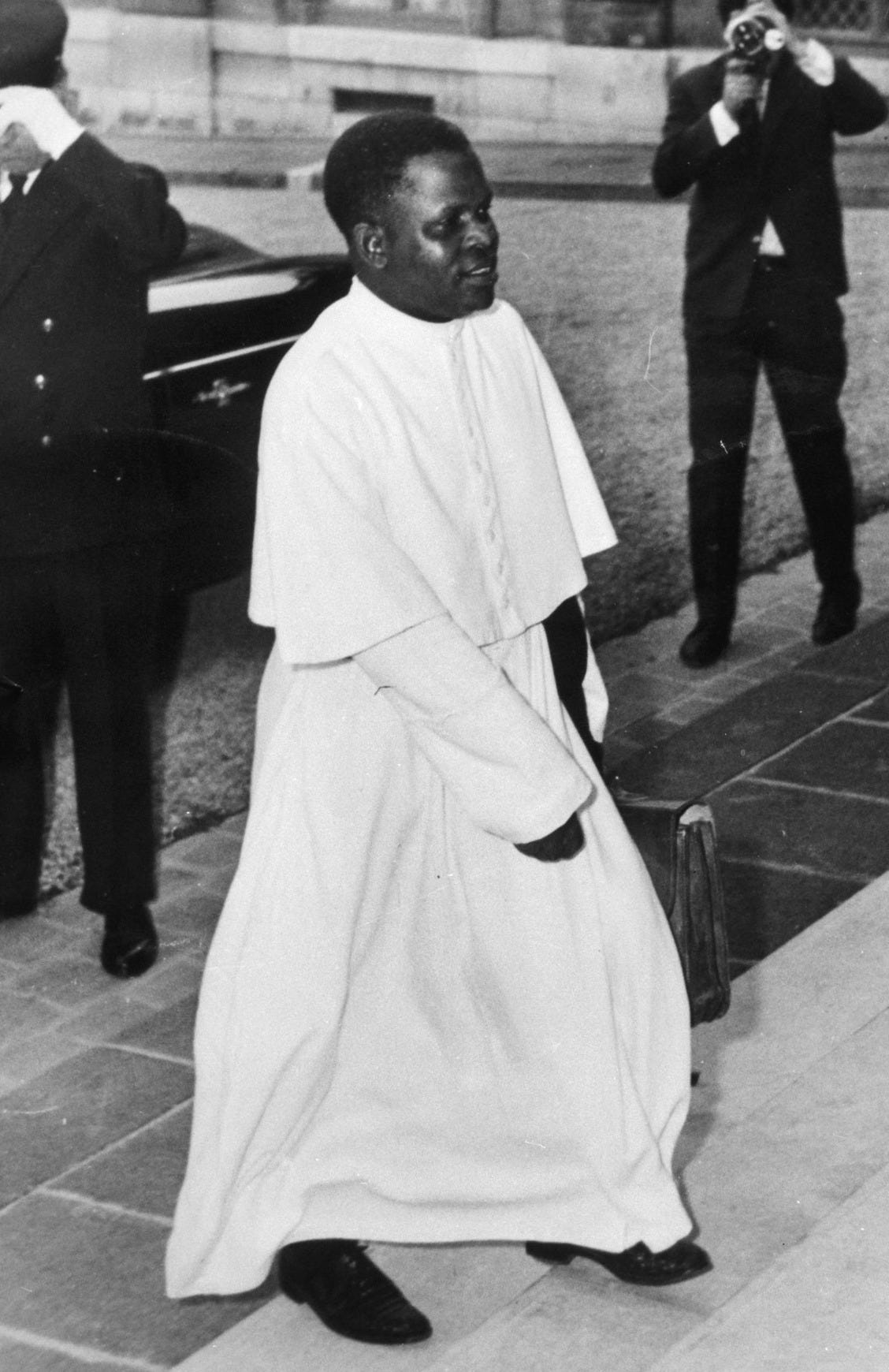

With the introduction of political parties by France, two emerged: the African Socialist Movement (MSA), advocating for a socialist economy, and the Democratic Union for the Defense of African Interests (UDDIA), a pro-French, mixed economy party led by Fulbert Youlou, a former priest. Youlou won the first pre-independence parliament elections in Brazzaville and became the inaugural president.

In 1958, Congo-Brazzaville, like most French African colonies except Guinea, opted to remain a colony. However, it did attain internal autonomy.

Congolese political parties devolved into ethnic rivalries, leading to severe riots in Brazzaville in 1959. To unify the country, by 1960, Congo-Brazzaville joined the wave of independence movements. Meanwhile, Ubangi-Shari became the Central African Republic and wanted Congo-Brazzaville, Gabon, and Chad to unite but leaders including Youlou rejected the union.

Abbe Fulbert Youlou (1960-1963)

Congo-Brazzaville, like many French African countries, signed cooperation accords with France, securing economic, technical, diplomatic, defense, monetary, and commercial assistance. There were 6000 French expats in Brazzaville (5th highest amount in French Africa). This agreement allowed Congolese businesses to export goods to France tariff-free, while France paid above-market prices for Congolese commodities, benefiting palm oil, cocoa, and peanut farmers. However, Congo-Brazzaville had to pay a premium for French manufactured goods. Many have called this arrangement "neo-colonial."

Youlou established a mixed economy, with French-run private businesses, small Congolese enterprises, and state-owned industries. Unfortunately, state ownership led to rampant corruption, with ministers embezzling funds and mismanaging state enterprises. Ministers in Congo-Brazzaville ran state owned enterprises to the ground, and they used public funds to set up bars, night clubs and diamond smuggling ventures. Marketing boards were set up in timber and coffee which would pay workers/farmers a fraction of the international price.

Critics faced harsh treatment, and Youlou favored the south. By 1963, protests by trade unions and youth groups led to his removal by army officers. Youlou cried, fainted, and called the French President Charles de Gaulle saying “My general, I signed (my resignation)”. He went to France in exile, and then France told him to go away, and then he settled in Madrid, Spain.

Alphonse Massamba-Debat (1963-1968) “Mah-sam-bah De-bah”

Under the leadership of Alphonse, Congo-Brazzaville established a one-party state called the "National Movement of Revolution" and initiated the nationalization of industry from foreign firms. Many French Expats left.

Alphonse's Marxist state operated on three tiers: state-owned enterprises, joint partnerships, and private enterprise. Alphonse made state owned sugar cane plantations, textiles, cement factories, glass factories, electrical utility, and construction firms. He also nationalized tobacco. However, agricultural plans often fell short of targets due to urban migration and a lack of commercial agriculture expertise.

In addition, the state owned enterprises (SOE) were incredibly unproductive, as the remaining few expats still produced most of the goods and services of the economy. How were the SOEs inefficient? Government ministers abused their power and stole money from the SOEs. In addition, the civil service became bloated - 62% of the entire budget was allocated to civil service salaries. His own ethnic group, the southern Kongos were favorited in employment and opportunity.

When the World Bank looked at Congo-Brazzaville’s first five year plan, they criticized it and said “It contains little analysis and hardly any guidelines for action.”

Despite being a Marxist, Alphonse still valued foreign investment and courted investors in sugar, timber, and potash. The result was Congo-Brazzaville’s main export was selling wood.

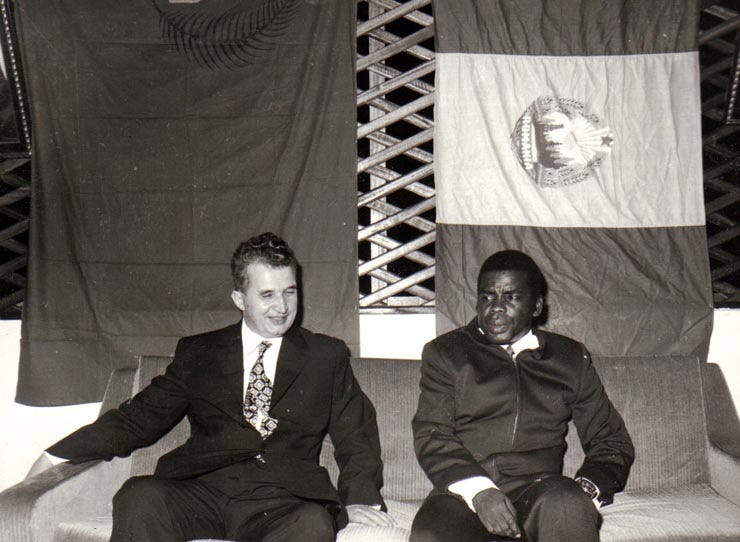

Geopolitically, he balanced aid from North Korea, China, and the Soviet Union and France.

Alphonse’s tribalism and failed policies were too much for the military to bare. The military overthrew Alphonse’s government.

Alfred Raoul (1968-1969)

Alfred, the former PM served as interim president before Marien Ngouabi took over.

Marien Ngouabi (1969-1977) People’s Republic of Congo, “Mah-ree-en Ngo-ah-bee”

In 1970s, Congo-Brazzaville was declared as an “Afro-Marxist State”, and Ngouabi, a Mbochi Northerner, shifted power away from the south. He maintained relations with the USSR and France.

Unlike his predecessor who courted foreign investors, Ngouabi nationalized those foreign enterprises and created new state-owned enterprises. However, these ventures led to political patronage, and operational inefficiencies, exacerbated by lack of qualified staff. These firms were over employed, encouraged by trade unions and alarmed public finances with foreign currency borrowing. The government ministers chose overemployment and raising salaries over investing in capital expenditure (improving machines, factories, etc.) due to Brazzaville’s chronic unemployment problem with rapid urbanization. This hurt Congo-Brazzaville in the end as productive capacity declined sharply. The government destroyed its own national textile mill.

Striking Oil: In 1972, two offshore fields came onstream and Congo-Brazzaville became an oil exporter, transforming the economy, with Congo-Brazzaville’s government owned oil firm - Hydro-Congo leading the way. Oil replaced timber as Congo-Brazzaville’s biggest foreign exchange earner. The government thought they had an infinite money machine, and they massively increased foreign borrowing and made new public enterprises in oil refineries and state run farms. Foreign multinationals would have to get licenses from the government and pay Hydro-Congo royalties and taxes on profits. The Congo-Brazzaville benefited from the first oil boom from 1973-1981.

Thanks to oil, increasing government spending, the standard of living of the Congolese improved. There were more shipyards, more investments, palm groves, match factories, health centers, cement factories, and schools.

Almost all of the state-owned enterprises couldn’t run a profit as they were operationally inefficient as they refused to lay people off or make decisions based off profit instead of political patronage. These unprofitable firms were subsidized by oil money.

In 1977, Ngouabi was murdered. An interim government was appointed by Congo Brazzaville’s political party.

Joachim Yhombi-Opango (1977-1979), “Jo-ah-keem Yohm-bee Oh-pahn-go”

Joachim ruled for two years before he was overthrown. Joachim never solidified his power as he had to share it with other military leaders. Accused of corruption and deviation from party directives, Yhomby-Opango was removed from office in 1979.

President Denis Sassou Nguesso (1979-1992) “Deh-nee, Sass-oo, Ngweh-soh”

After seizing power, Denis Nguesso purged his rivals and balanced ties between France, the Soviet Union, Cuba, and China.

Initially, high oil prices due to the Iranian Revolution and Iraq-Iran war benefited his oil-rentier state regime, however, by mid 1980, Congo-Brazzaville started to have debt problems.

Oil prices were tanking, which meant so did government programs, government owned firm investment expansion, and subsidies. In 1985, interest on debt became 45% of Brazzaville’s government revenue, forcing Congo-Brazzaville to borrow more to sustain spending.

This unsustainable cycle ultimately led to austerity measures in 1987, including privatization, fuel subsidy removal, and bureaucracy reduction. The attempted privatization of Hydro-Congo sparked outrage, with many seeing it as neocolonialism to foreign multinationals.

A failed coup attempt followed, leading to Nguesso's increased brutality and unpopularity. By 1990, the country was bankrupt, and Marxist-Leninist ideology was abandoned.

To secure an IMF loan in 1991, Congo-Brazzaville adopted multiparty democracy, but this only exacerbated tribalism, a concern that had led many African leaders to reject multi-party democracy to begin with.

In 1992, when Congo-Brazzaville had elections between Denis, Bernard Kolélas, and Pascal Lissouba, the former Prime Minister. Nguesso lost to Pascal Lissouba.

Pascal Lissouba (1992-1997)

Lissouba attempted to form a coalition government with Nguesso, but it collapsed when Lissouba sought to end the oil rent patronage system, a move Nguesso refused to support. Lissouba then dissolved parliament, triggering riots. He called for new elections, but the opposition boycotted the results and the second round. Mass protests erupted in Brazzaville. Distrusting his military, Lissouba created a personal militia, the Coyotes, comprising members of his southern ethnic tribe, the Bandjabi.

Congo-Brazzaville Civil War #1 (1993-1994)

Lissouba wasn't alone in forming a militia. Denis Sassou Nguesso and Bernard Kolelas followed suit, creating the Cobras and Ninjas respectively, drawn from their Mbochi and Kongo tribes.

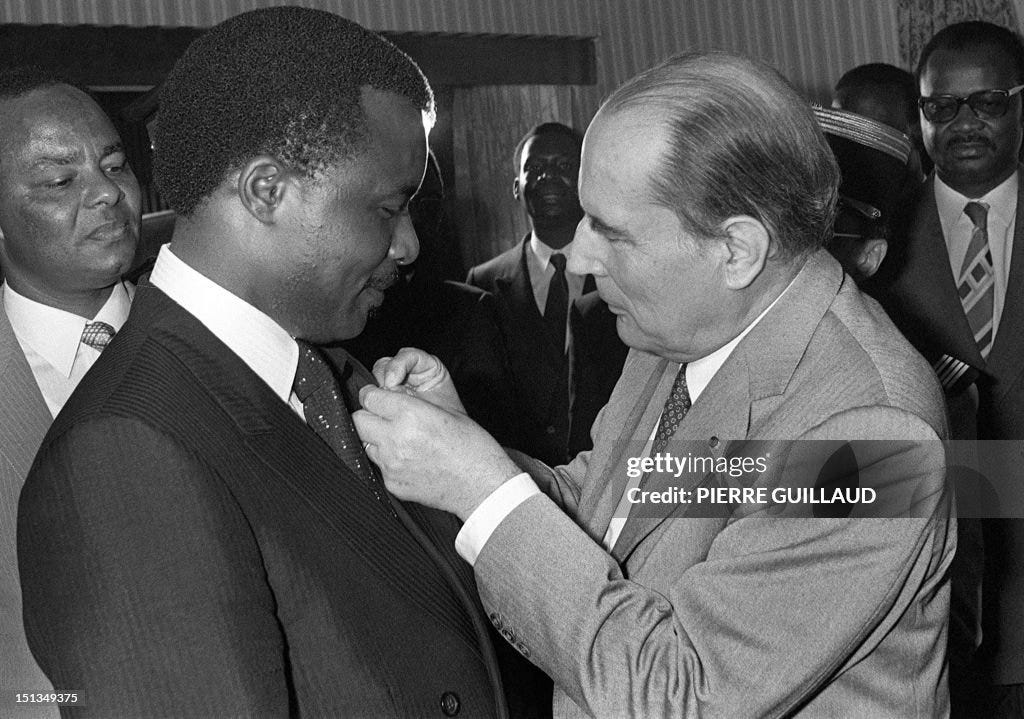

This escalation led to a two-month war that claimed 2,000 lives. In the end, Lissouba maintained power while Denis fled to France, where he enjoyed the support of President Mitterrand and Jacques Chirac, his personal friends.

New riots erupted in Brazzaville in 1994 as France devalued the CFA franc to bolster exports. While devaluation made exports cheaper and more competitive, it also drove up the cost of imports, fueling inflation and sparking widespread protests.

Congo-Brazzaville Civil War #2 (1997-1999)

In 1997, legislative and presidential elections were scheduled, prompting Denis Sassou Nguesso's return from France to run. He also readied his militia, the Cobras, to potentially disrupt the elections if he lost. Clashes between Denis' supporters and Lissouba's campaign team escalated into violence, leading Lissouba to order the arrest of Denis' associates. The Cobras resisted, sparking the second civil war. As the conflict raged on, the country defaulted on its foreign debt. Kolelas' Ninja militia joined forces with Lissouba's Coyotes to counter Denis' Cobras. On the brink of defeat, Denis received crucial support from Angola, whose government was fighting its own civil war against American-backed anti-communist rebels.

Angola's intervention was motivated by Lissouba's anti-communist support for the rebels seeking to topple President Eduardo dos Santos' communist government. dos Santos backed Denis to eliminate Lissouba. If you want to learn more about Angola read here.

President Denis Sassou Nguesso (1997—Present)

The civil war ended in 1997 with Denis Sassou Nguesso's victory, forcing Kolélas and Lissouba into exile. Lissouba was also convicted of embezzling $150M in oil revenues in private Belgian bank accounts. Many believe France and Gabon's Omar Bongo backed Denis, ensuring his militia's funding. Nguesso made a truce with the militias, ending the war that claimed 25K lives and displaced 200K. He has since changed the constitution to extend his power, a tactic used by other African leaders. Conflicts with the Ninja militia resumed in 2002-2003 and 2015-2016 due to economic neglect and failed integration, and in 2016 there was electoral fraud. Both times, the Ninjas lost, and tens of thousands were displaced.

Denis attempted to diversify the economy from oil with a national development plan, but results were lackluster, except now Congo-Brazzaville also exports billions in copper mining.

Denis restructured the state run oil firm, Hydro-Congo to the “National Petroleum Company of Congo (SNPC)”. This came right on schedule for the China fueled an oil boom from 2000-2014, and Congo-Brazzaville strengthened ties with China through "oil for infrastructure" projects. The country also undertook an IMF program in 2002 to recover from the civil wars, and received London Club & IMF Heavily Indebted Poor Countries’ debt relief in 2007 and 2010, bringing down its Debt from $6.7B to $2.8B. For receiving IMF debt relief, Brazzaville had to abide by anti-corruption measures.

However, after the 2015 oil crash, Congo-Brazzaville borrowed more to make up for loss oil revenues, leading to technical defaults in 2016 and 2017. The British-American construction firm Commisimpex sued Congo-Brazzaville for not paying €1.2B worth of bills. France and the Central African Franc countries pressured the government to take a ~$500M IMF loan.

#1: Fiscal discipline: The country reduced spending, transitioning from budget deficits to surpluses between 2018 and 2023, except for 2020 due to COVID-19. Austerity measures, such as reducing fuel subsidies and increasing VAT taxes, were implemented, but angered the urban population.

#2:Data Transparency. Historically opaque, Congo-Brazzaville began publishing basic debt financial data in 2019, marking a significant step towards transparency.

#3: Debt restructuring: The country renegotiated debts with China, delaying $370M in payments. However, talks with oil traders (like Glencore, Vitrol, Gunvor, and Trafigura) remain ongoing, with notoriously opaque deals and prolonged negotiations.

Concluding Thoughts

Decreased Marxist Historian, Walter Rodney, wrote his 1972 book, "How Europe Underdeveloped Africa". It was a groundbreaking exposé on the harmful effects of colonialism, challenging the prevailing view at the time that colonialism was beneficial. While the book was influential, its communist policy prescriptions don’t have a good track record. Congo-Brazzaville followed most of them, as Brazzaville nationalized resources and industry from foreign ownership. Instead of collective prosperity it led to kleptocracy and corruption by the political elite.

Denis’ son stole $50M from the Brazzaville treasury to buy a luxury apartment one of Trump’s buildings in Manhattan , a penthouse in Miami, and luxury real estate across six European Countries. Denis' daughter ,Claudia, also siphons funds from Congo-Brazzaville’s state owned enterprises to buy real estate in America and Europe. Meanwhile, the country has over hundreds of millions in arrears as of 2023 to countries like Brazil, India, Russia, UK, and the European Union.

If the Nguesso family isn’t careful their country could be ripe for a coup just like their neighbor in Gabon.

Two things :

1. the Copper exports are fake. Or rather, it's probably mislabeled shipments from DRC. ITIE data on copper production does not match at all.

2. The 17 000 deaths from the railway are not from a crackdown on a rebellion but from the construction itself. It was built on the cheap with mostly bare hands (they barely used any dynamite) and a huge part of those deaths came from diseases because most of the workforce was from Chad as colonial companies were unable or unwilling to release local labor for this project.

No I certainly did not know about the two Congos. Thanks.