Questions About Sovereign Debt & Currencies (Part Two of Debt Series)

What is the best metric to look at debt sustainability? What is good debt vs. bad dad for a country? What are exchange regimes? Your answers are here.

Last time, we spoke about America’s Debt. If you want to read about American debt read here:

U.S. Debt Part 1: The background Info

*Random fact, the Revolutionary War was funded not only by the rebels fighting for independence, but also by bankers in Paris, Madrid, & Amsterdam. It was their way of saying “screw Britain” for taking all the good territories on earth after the 7 Years war.

Question 1: What is the most important Metric to look at how fiscally sustainable a country is?

The world is in debt but there’s a huge difference between the developing and developed world’s debt markets.

Unfortunately, there is currently a really poor understanding of debt in common parlance in the globe.

For example, most people think the most important ratio is “debt to GDP”. 5 years ago, I was listening to a Ghanaian politician talk about how Ghana’s debt is “sustainable”. He would say “Ghana’s debt to GDP was lower than develop nations, therefore Ghana’s debt is sustainable”. To the untrained ear this sounds reasonable, but this is actually a slight of hand. He is correct that Ghana’s debt to GDP was lower than developed nations however that is the wrong metric to look at. If you were knowledgeable about how to look at sovereign debt you could see Ghana’s default coming a mile a way when certain conditions are met. Unfortunately, those conditions have been met and Ghana is virtually bankrupt (again).

Let me explain:

The Debt to GDP is an important ratio to understand debt levels, but looking at the debt to GDP ratio alone, would not give you predictive power on which countries are going to have a sovereign default. Here is a sample of developed and developing countries debt to GDP levels:

As we can see Japan, Singapore, Italy, Bahrain, America, Spain, France and Belgium have Debt to GDP levels that exceed their GDP. Japan’s debt is 262% times its economic output.

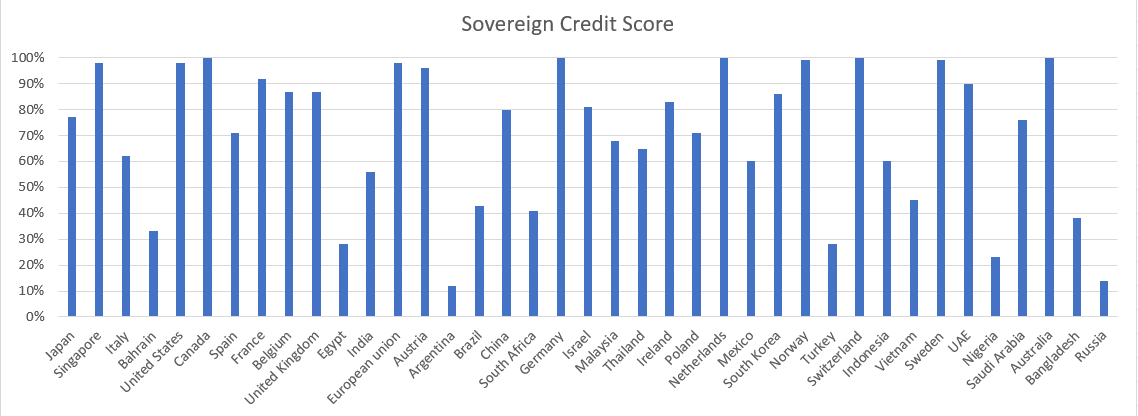

Despite their debt levels, these nations have incredible credit scores. In fact, sovereign credit scores have a weak correlation with debt levels. Based on this dataset of countries, the correlation is 15%. The correlation is pretty close to zero.

To spell out what this means in a 2x2 matrix:

This means there are a fair number of countries with high debt to GDP ratios with amazing credit scores (like America, Canada, and Singapore).

There are also a fair number of countries with high debt to GDP with terrible credit scores (Bahrain and Egypt).

There is also a fair number of countries with relatively low Debt to GDP levels with amazing credit scores scores (Switzerland, Sweden, Saudi Arabia, Australia).

Lastly, there are a fair number of countries with relatively low Debt to GDP levels with terrible sovereign credit scores (Argentina, South Africa, Turkey, Nigeria). In other words, you can’t look at the debt to GDP ratio of a country and then say “that nation’s debt is not sustainable!”

Let’s line up these same countries by their average sovereign credit scores and you’ll see what I mean below. Just from examining the two graphs, you won’t see a trend:

A far more useful and predictive metric to look at risk of default is the annual interest payments or the annual debt service as a % of government revenue.

For America, in 2022, America’s net interest payment on debt was $475B, but America’s government revenue was $4.9T. That means America’s interest payments was roughly 10% of its government revenue. I would personally like that number to be lower, but that level is sustainable. (It will be increasing however). Meanwhile. in 2022, Nigeria’s interest payment as a percent of government revenue was 83%.

When you look at interest payments, or a government’s debt service, as a % of the government’s revenue, instead of just looking at total debt as a % of total economic output the credit ratings of a nation make much more sense. Unfortunately most of Africa’s bonds is considered to be “junk bonds” except Botswana and Mauritius.

Because of the higher sovereign credit ratings a country has, it makes its borrowing costs easier than other nations’.

For example, on the 10 year bond (for those who don’t understand this concept, it basically means the government is asking for money and it will pay back the money in periodic biannual payments in 10 years with interest), America pays a 4.44% yield on its 10 year bond as of 2023. America’s sovereign credit rating is averaged out to a 98 out of a 100. For other advanced economies with good credit scores, Canada borrows at 3.92% for a 10 year and Germany borrows at 2.74%.

For Mexico, Brazil or South Africa, three “upper middle income countries” or “advanced developing countries”, they have average credit ratings between 40% to 60%, when they borrow, they are deemed more risky. Their rates are between 10% to 12% for a 10 year bond.

For lower middle income countries with poor credit scores like Kenya & Pakistan , they borrow at 16% for a 10 year bond.

Countries like Chad, Central African Republic, and Malawi have financial systems that are too underdeveloped to borrow 10 year bonds in global markets as of September 2023.

In short, the riskier the country, the higher the debt service costs.

What are some factors that a country can look at for debt sustainability?

Entire thesis papers can be written on this, and I have read a few. It’s more of an art than a science.

But in short, developing/emerging countries have:

1) Higher histories of defaults or Bailouts by multilateral institutions. A higher history of being “irresponsible” with debt makes developing countries become riskier to lend to. Argentina owes $33B to the IMF, the most of any nation and has defaulted on debt 9 times since its 19th century independence. As a result of mismanagement that continues today, Argentina as of 2023 is shut off from financial bond markets from being uninvestable.

America, post 1945 when America created the international order, has never officially defaulted on its debt obligations in modern history. America comes close with debt ceiling debates, but America has never defaulted from an inability to pay. Other nations included in the pristine record include Canada, Denmark, Belgium, Singapore, and New Zealand. Nigeria, however, had to restructure and reschedule its debt payments in the early 1980s when crude oil, which accounts for almost Nigeria’s export earnings, had a price collapse in real dollars from $148 per barrel in 1980 to $30 per barrel by 1986. Nigeria back then did not have the reserves or the sovereign wealth fund like Qatar or Saudi Arabia to cushion the plummet of crude oil prices. This is called foreign currency risk. If a country has an insufficient financial sector due to a lack of savings in the population. Then nations like Nigeria will borrow from abroad in US dollars. If their main commodity has a price collapse, then the US denominate debt becomes too expensive. The specter of the 1980s affects Nigeria today as it is seen as a much risky place to lend money to due to crude oil price dependence. Other African countries have a similar problem. Even today as of 2023, Nigeria has roughly $34B in reserves and has $2.3B in its sovereign wealth fund, which is not that much. A country should ideally have at least 6 months of import coverage, 3 months at worse case. Nigeria has 5.2 months as of August 30th. Saudi Arabia has nearly $800B in its sovereign wealth fund and 21 months of import coverage.

2) Developing/Emerging economies refuse to let their currencies float (this means, let markets determine their exchange rates) and instead these nations artificially anchor their currency’s value to the US dollar/a basket of currencies:

Because of currency anchors, these countries have to be concerned about their currency reserves and if they can maintain their currency anchor as they borrow in US-dollar denominated debt.

Developed/Emerging Countries will have currency anchors not because they are stupid, but because they know the free market would punish their currencies’ value which would make it inordinately expensive for these countries to buy food, medicine and fuel from abroad. Poor nations’ officials believe and experienced starve, lack of electricity, and depletion of medical inventory if/when played free markets , so these nations have currency anchors so their people can import food, fuel, and medicine from abroad at relatively affordable prices.

Examples of nations that their currency’s value be (almost) completely determined by supply demand are America’s dollar, the European Union’s euro, the British pound, the Swedish Krona, the Japanese yen, and (for now) the Mexican peso. These nations have free floating currencies.

Then there are currencies that are mainly free market, but have more market intervention than free floating currencies. This includes the Turkish lira, the Thai baht, the South African rand, the New Zealand dollar, the South Korean won, the Israeli Shekel, the Indonesian rupiah, the Indian rupee, and the Brazilian real. These are floating currencies.

Then there are countries that have crawling pegs/stabilized arrangements. This means the nation’s central bank has the currency anchored to a currency/currencies but will allow gradual appreciation or depreciation of their currency at a certain range:

China, Argentina, the Philippines, and several African currencies have this arrangement from Ghana, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Tunisia, Egypt, Tanzania and etc.

Then there are conventional pegs. These are currencies that maintain a one to one exchange rate with another currency. The French West and Central African countries maintain a anchor consistent with the euro. Eswatini, Lesotho, and Namibia maintain their currency anchored to the South African rand. Nepal and Bhutan maintain their currency anchored to the Indian rupee. Oman, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Qatar anchor their currencies to the US dollar, which is conventionally called “the petrodollar scheme”.

Why do poor/middle countries borrow?

You might ask since poorer countries pay higher rates is “Why do poorer countries borrow at all?”

Countries, especially African countries need to borrow to have economic cushions in case commodity price plummets (African countries depend on commodities for export revenues, DRC with copper, Ivory Coast with cocoa, Nigeria for oil). These countries also need to borrow to buy food, medicine, fuel, machines, or cars or build roads.

When is borrowing good or bad for developing/emerging economies?

Borrowing can be good when it is used for productive investment build or maintaining roads, hospitals, or schools. (Even then the economic growth and government revenues received from state owned firms or taxes from projects must exceed the borrowing costs for the project to be truly sustainable or productive). Borrowing is good when it is for future economic gains.

Borrowing can be bad when used for:

Non-productive investment: Building ports that don’t have any commercial traffic. Like when Sri Lanka defaulted on the Hambantota Port and leased it to China for 99 years. (China is NOT engaging in debt trap diplomacy btw, that is nonsense, I will debunk that later). Many developing countries have this paradigm of “build it and they will come”, but sometimes infrastructure projects fail.

Borrowing for consumption. Unfortunately this is very prevalent in the developing world and it is hard to stop:

A) Borrowing is bad when governments are using borrowed funds to spend on poor people to secure votes for an election. This has happened routinely in Ghana since it has become a multiparty democracy since 1992.

B) Borrowing is bad when governments are borrowing funds to fuel today’s consumption. A perfect example is consumption fuel subsidies. This is when the government pays to make fuel lower than it should be for consumers. It is really hard for developing countries to scrap fuel subsidies because their people can’t afford to pay market price for fuel or gasoline. Scrapping fuel subsidies can cause riots. Kenya tried to scrap fuel subsidies in August 2023, but without subsidies, inflation skyrocketed and cost of living surged for motorcyclists. Removing fuel subsidies is economically good for the long run, but political suicide.

C) Borrowing is bad when government owned corporations borrow money and then loot the cash instead of using it for business activity. A perfect example is when Mozambique’s government owned firms issued $2B in bonds to fund tuna fishing and other projects. But the government owned firms defaulted on the loan due to rampant theft. Credit Suisse, one of the lenders was damaged from lending this money. This hurt Mozambique’s reputation as a result of this scandal. Mozambique was then cut off from Western donors for financial support, and Mozambique defaulted in 2016.

Informative and easy to understand, very educational.