The Economic & Geopolitical History of Mali, Part 1: Gold & Medieval Mali

From One of the Most Important Empires to One of the Poorest Countries

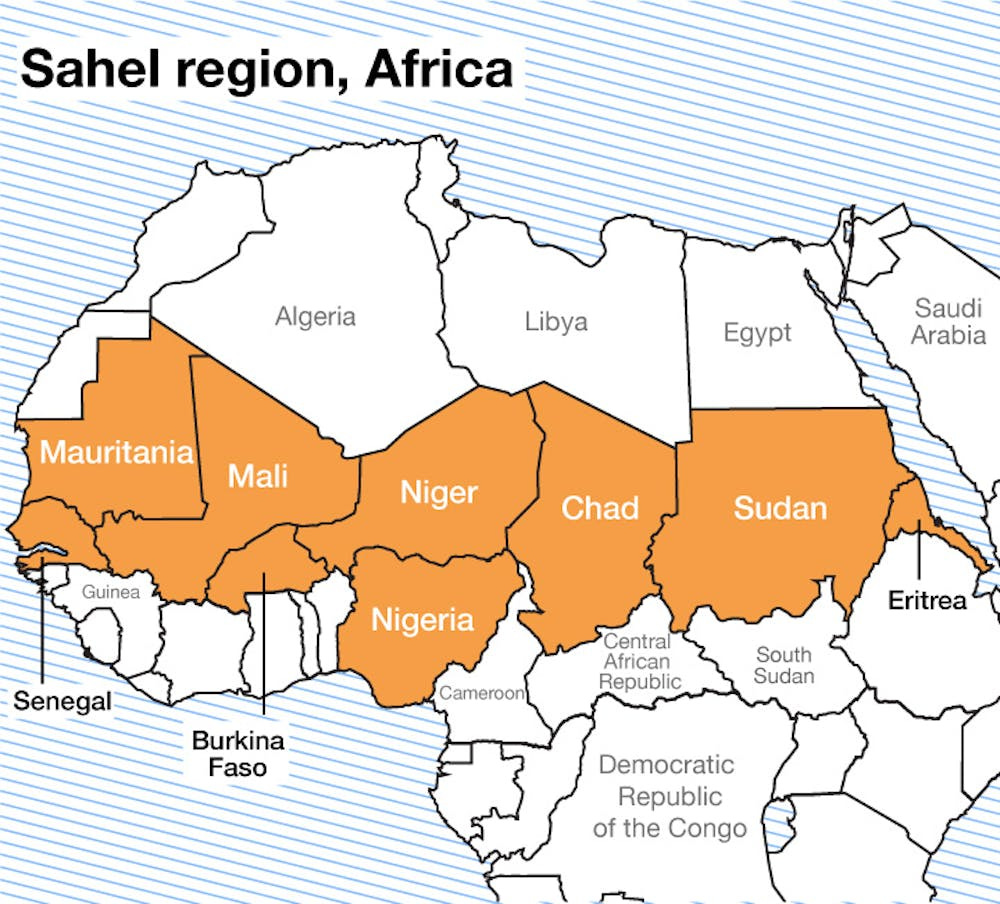

Mali, a West African nation in the Sahelian region, is 95% Muslim, with over 20+ ethnic groups including Fulani, Mande people (Bambara, Mandinka, Soninke), Songhai, Tuareg Berbers, Arab Berbers, and more.

The Sahel, is below the African Sahara desert, but above the costal areas. Sahel is Arabic for “shore”, as the Amazigh/Berbers (North Africans) & Arabs analogized the desert as a “sea of sand”, conceived their camels as “boats”, and thought of Empires in West Africa, like Takrur, Ghana, Gao, Mali, & Songhai as “ports” to obtain gold, ivory, slaves, and other goods.

With a population of 24M, Mali is a relatively sparsely populated. The country is larger than California and Texas combined. It is also unfortunately a low income country and is the 6th least developed nation on earth, with almost two-thirds of the Malian population working as subsistence farmers. In 2022, the average Malian farmer produced 1.67 tons of food per hectare, which is below the average for food deficit countries, 2.35 tons per hectare. As of 2024, Mali has the 3rd worst credit rating in Africa, as its bonds are considered “junk”. 20% of Mali’s government budget comes from foreign aid.

The country used to be pretty socialist (by “socialist” I mean the government owned major businesses instead of private enterprise. I do not the other definition - worker owned enterprise), but after a series of 19 IMF loans (Mali owes the IMF $92M), the government now just owns (or partly owns) 45 enterprises, including mining, banking, utilities, telecom firm, cotton processing, cigarettes, sugar, and the airports.

Mali is named after the Medieval Malian Empire, and Mali is a Mandinka word for Hippopotamus. The modern day country of Mali and the Medieval Malian empire are not entirely identical. The Malian Empire was a massive empire that incorporates modern day Mali, Senegal, Gambia, Mauritania, Guinea, and parts of Northern Burkina Faso & Ivory Coast. The modern country of Mali is an artificial construct created by France that merges the Mandinka South and the Tuareg Berber North.

The Niger River divides Mali into the arid, sparsely populated Arab &Tuareg Berber-dominated North (known as “Azawad”), and the fertile, densely populated Blacker Mandinka (also known as Mande or Malinké) South. Tensions persist between the Tuareg minority and Mandinka majority, fueled by historical conflicts and marginalization. Bamako, the capital, enjoys better services, contrasting with underdeveloped Tuareg regions. If you read my series on Niger or Chad, you’ll be quite familiar with other Sub-Saharan African majorities “oppressing” the Tuareg & Arab-Berber minorities.

The issue is a product of colonialism, as the Tuareg Berbers were divided by the Europeans in five separate countries (Mauritania, Algeria, Burkina Faso, Niger, & Libya). The Tuareg Berbers have tried to secede from Mali four times since Mali has received independence.

Mali’s Resources

Mali heavily relies on gold exports, which account for the majority of its foreign currency earnings and 25% of its national budget.

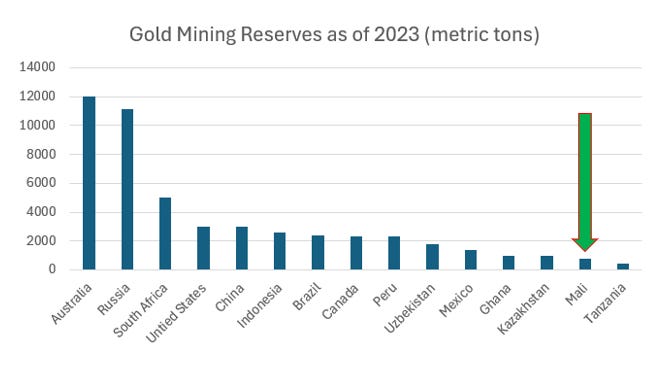

Despite its historical significance in medieval gold trade, Mali's influence in the modern global gold market has diminished. Geological seismic studies indicate that Mali possesses 1% of global gold reserves remaining, which still places Mali in 14th place globally.

In terms of gold production & exports, Mali is in 11th place in both respects.

Unfortunately gold is not much of a money maker for Mali like oil is for Gulf states. When you take Mali’s gold exports and divide that export revenue by the population, Mali makes roughly $330 per person selling gold. Just to compare, UAE makes over $10K per person from crude oil & gas exports. Speaking of UAE, Mali’s largest trading partner is selling gold to UAE (Switzerland is a close second).

Unfortunately, Mali has horrific record keeping of its gold exports. Mali has the worst illegal gold trade discrepancy in all of Africa.

You see there are two forms of production of gold in Mali: Industrial production done by multinational firms like Barrick Gold, B2Gold, & Sky Gold in Canada, South African AngloGold Ashanti, and Resolute Mining in Australia. These companies bring their capital to make massive gold mines to extract gold on the ground. Industrial mining is taxed at 25% and its traceable.

Then there’s artisanal gold production, which is the type of gold mining that Africans have done for millennia since the days of the Ghana Empire - use your hands to dig up gold. Nowadays, Malians use pick axes and shovels.

Artisanal mining often escapes the authorities. If you want to see a video of artisanal mining, click here. In general, many artisanal mining Malians hate export taxes, so they use clandestine networks to bypass state regulatory bodies and sell their gold without paying taxes to the Mali government. Unfortunately, artisanal mining can be unsafe. In January 2024, the Mali government uncovered 80 dead bodies from a collapsed illegal gold mine.

At this point, industrial mining production is tiny compared to artisanal mining. The difference is in the tunes of billions of dollars.

Gold was not always Mali’s biggest export. All the easy gold was already extracted through the Medieval trade with Arabs. At independence in 1960, Mali’s main exports were cattle, peanuts and cotton. By 1980s, cotton & cattle exports made up 70% of export receipts. But since 2000s, due to foreign investment, new gold mines were excavated, and Mali returned to being a gold hub as it was in Medieval times. Now, Mali’s ability to purchase necessary imports (medicine, food, fuel), spend on necessary services, and subsidize & support industry is more or less dependent on the price of gold.

Below you see a chart on how average Malian incomes have historically went up when commodity prices are high, and Malian incomes have fallen or stagnated when commodity prices fell or stagnated. From 1969 to early 1980s, Mali was fast growing due to a cotton price rush. From early 1980s to 2000s, was two wasted decades due to low cotton prices. Then Mali’s growth rebounded in the early 2000s due to gold becoming their main export, and it has been stagnating since 2014 as gold prices have.

Also, unfortunately, Mali doesn’t really sell enough gold (legally). Almost every year Mali spends more than takes in.

Mali is the opposite of a gulf state. Gulf states like Oman or Bahrain usually sell more oil & gas from trade than they spend. As a result, Oman and Bahrain have so much dollars that they buy US assets like treasury bonds and real estate in their Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF). As of 2023, Bahrain’s SWF has $18B and Oman’s SWF has $47B. As of May 2024, Mali doesn’t have one.

Luckily, gold is having a price boom in 2024, so maybe Mali will be able to capitalize on that.

Pre Colonialism: The “Western Sudanic” Empires

The Arabs referred to this region as “Bilad al-Sudan” which is Arabic for “land of the Blacks”.

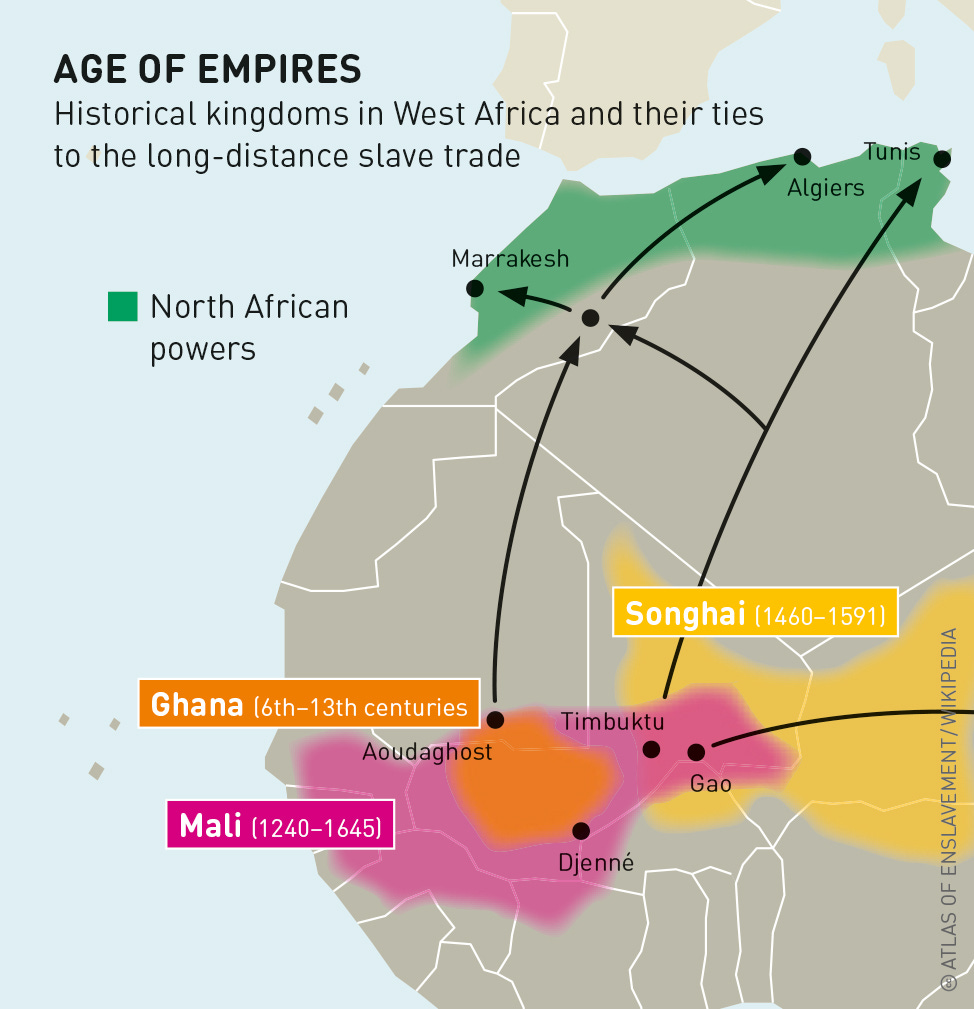

Below you will see the locations of the three West Sudanic Empires (Ghana, Mali, Songhai) and its relations with North Africa.

What’s interesting about these Kingdoms was how sparsely populated they were. Due to drought, diseases (Malaria, Tsetse fly), and no sanitation systems, life expectancy was low, birth rates and death rates were high so populations increased gradually.

In the year 1000 AD, during the Ghana Empire, the population of this empire was estimated to be 3.3M. By 1600 AD, right after Morocco destroyed the Songhai Empire, the population of the empire doubled to 6.7M. Despite their sparse populations, the Western Sudanic Empires controlled vast territories totaling 3 million square kilometers, comparable in size to India or most of West & Central Europe. Because land was so abundant, feudalism never developed in the Western Sudan as it did in Ethiopia, China, or Europe. In Europe, the Sovereign’s right to taxes was primarily based on land ownership. In West Sahelian Africa, the Sovereign’s right to taxes and service was based mainly on political and military coercion.

Ghana Empire or the Wagadou (100 AD?ish — mid 1200s)

Mali's origins trace back to the Ghana empire or Wagadou, established in the 2nd century in modern-day Southeastern Mauritania/Southwestern Mali. Though known as "Ghana" by contemporary Arab geographers like al-Fazari, the locals referred to themselves as the Wagadou.

Unfortunately the Ghanaians didn’t write much, so the vast majority of what we know about them come from traditional oral history given from Griots, archeology, or the contemporary Arab merchants (like Al-Fazari & Ibn Hawqal) who came to the area. In fact some Arab-Berbers, called the Sanhaja also settled in Ghana.

Griots, also known as "Gewel," "Jeli," or "Kevel," are multi-talented figures in West African countries, embodying roles as musicians, praise singers, poets, historians, and storytellers. They preserve oral traditions, stories, and poems of their ancestors, often recounting history through song and dance.

Most of what we know about these empires mainly comes from the Arab Chroniclers, and then modern historians synthesize Arab history with Griot oral tradition and archaeology.

The Ghana empire, ruled by the Black Mande speaking, Soninke people, controlled gold and trade routes, imposing heavy taxes on Arab/Berber/Tuareg traders. The Ghanaians traded gold/ivory/slaves with the Berbers/Arabs/Tuaregs in exchange for salt and luxury items. This was called the Trans-Saharan (Slave) trade.

Why salt? Salt was scarce for Sub-Saharan Africans. Black Africans used salt as food preservative for fish, veggies & meat, for rituals, and for traditional African medicine. Remember electric refrigerators didn’t exist yet!

Through trade, a few Ghanaian merchants converted from pagan animism (i.e. serpent worship) to Islam by the 7th century. However, the political elites were still pagans. The Ghana Empire also conducted slave raids on the Africans south of their Empire to fuel their slave trade to Arabs.

By the 8th century, a rival empire called Gao emerged, which competed with Ghana to sell slaves and gold to the North Africans.

Unfortunately, the Moroccan Almoravid Berbers destroyed it in the 11th century. The Moroccans temporarily took Ghana’s gold and trade caravans, and enslaved pagan Black Africans.

The Fractured Empires

The Moroccan conquest of Sahelian West Africa only lasted for a bit, until Ghana quickly resurrected as separate empires in Wagadu, Diafanu, and Sosso (or Susu) empire and other Black African states emerged.

The Mali and the Sosso Kingdoms were the strongest Kingdoms of the fractured states of Ghana. According to the Mandinka people’s poem “The Epic of Sundiata”, Sundiata Keita, a Malinké of the Mali Kingdom, united the Mande clans against the Sosso, to create the vast Malian empire in 1234 AD. (Malinké are also known as the Mande, Mandinka, or Mandingo people. Mali-nké means “people of Mali” and Man-dinka means “people of Mande” ).

The Mali Empire (1235-1672)

After its establishment, the Mali Empire controlled key gold cities like Gao, Timbuktu, Jenne, and Niani, facilitating trade in gold, slaves, ostrich feathers, hides, kola nuts, and ivory with Arabs and Berbers. Taxation of Arab/Berber merchants entering the empire funded a vast slave army to protect trade caravans. At its height, the Mali Empire supplied two-thirds of gold in Afro-Eurasia, primarily exchanged for salt & luxury goods with North Africans & Arabs. Then North Africans & Arabs sold that gold at a high mark up to Europeans.

Socially, the Mali Empire had a diverse slave caste system, ranging from poor to wealthy slaves, some holding positions of authority. Certain tribes were considered servile, forbidden from intermarrying with free people, had no inheritance rights, and performing various duties for the ruling class. Some slaves were debt servants, war prisoners, seized people from raids, and criminals. There were also manumission clauses for freedom.

Contemporary Arab Chroniclers described Mali as a subsistence agrarian federation with a wealthy royal elite, lathered in gold. The empire's political structure included 12 clans governed by regional kings under the Mansa's (Emperor’s) rule. While Islam was the religion of the elite, animist religions prevailed among the masses who were farmers, fishermen, or cattle herders. The Emperor’s family was the Keita Dynasty.

Sometimes the empire was stable, other times it was Game-of-Thrones style Chaos. The Empire collected taxes, each vassal state had its own form of autonomy, and used salt, gold nuggets, and cowry shells as currency. Each Mansa would make a pilgrimage to Mecca.

Chronicles of the Empire:

After the first Emperor, Sundiata died (either through being drowned or shot), his three sons Wali (Uli) , Wati, and Khalifa successively rose to power. Wali and Wati made some contributions, but Mansa Khalifa was apparently insane and killed his own people when he practiced archery. Khalifa was killed by Mansa Abu-Bakr, who was killed and succeeded by a freed slave-turned-military commander, named Mansa Sakura, briefly ending Sundiata’s lineage as Mansa of Mali.

Mansa Sakura is underrated, as he was the original African military strongman, that conquered the Gold city of Gao and brought stability to the empire. Sakura was killed on his way back from his pilgrimage to Mecca.

A descendant of Sundiata, named Qu, came back to the throne, restoring Sundiata’s lineage. Apparently Mansa Qu, led an expedition to the Atlantic Ocean, but they presumably died during their travels since they were never heard from again.

After Qu died, the famous Emperor, came into power - Mansa Musa or “Emperor Moses”. Musa expanded the empire's territory(conquering & enslaving 24 cities including Tuareg Berber’s Timbuktu), amassed vast wealth, and undertook a renowned pilgrimage to Mecca loaded with slaves and gold, demonstrating Mali's riches to the Arab world from Cairo to Mecca. He brought so much gold that it devalued the price of gold in Mamluk Egypt for a decade. Egyptians and Arabs chronicled this event which spread around Arabia and Europe about the riches of Mali. The Arab, Ibn Battuta gave his eye-witness account of Musa’s wealth.

That publicity stunt allowed him to bribe off skilled Arab bureaucrats, architects, and scholars to make Mali a religious and geopolitical center. With all these skilled Arab artisans, they made Timbuktu University, which is actually a collective term for three mosques - Sankore, Djinguereber, and Sidi Yahya. The Mosques became a hub of Islamic jurisprudence, astronomy, and math.

Timbuktu and Gao formed the core of Mali’s economy and Timbuktu became a massive cosmopolitan city with Arabs, Berbers and Africans living there, supporting a population of 100K people (which was big in 14th century).

After Musa's death, subsequent emperors lacked vision. Mansa Magha ruled for only four years before his death, and then his brother Mansa Suleyman ascended to power. Suleyman faced rebellions from vassal states unhappy with Mali's slave raids and high tribute taxes. These states broke away from the empire which was a problem since Mali heavily relied on slaves for its economy, with men working as miners, and women tending fields and guarding caravans.

With Suleyman's death, Mali fell under more incompetent rulers like Kassa, Jata, Musa II, Maghan, and Sandaki, leading to civil war, power struggles, bankruptcy, and regicide. Arab Chronicler, Ibn Khaldun described this period as corrupt and tyrannical, with some rulers mere puppets of the military. Some leaders succumbed to sleeping sickness spread by tsetse flies. Gao seceded from Mali under Musa II's rule, and by the 1400s, the empire was in ruins. Tuareg Berbers revolted, seizing Timbuktu and Walata, while the Mossi Kingdom took territory from Mali.

In the 1400s, Portugal also tried taking some Malian territory, but Mali was still strong enough to kill the Europeans with poison arrows.

During this time, Europeans weren’t technologically advanced enough to ramshackle the Africans yet, nor could they or their horses couldn’t handle diseases in Africa like the tsetse (set-see) fly or malaria. Back then the tsetse belt of Africa was known as “The White Man’s Grave”.

Portugal learned from their earlier mistake. Portugal bypassed North African middlemen by trading secretly with the Senegambian vassals of the Malian Empire and other African coastal states such as the Akan, Yoruba, Edo, Kongo, Angola, Mozambique, and the Swahili states. For Portugal, this eliminated high markup prices charged by North Africans for goods transported through the trans-Saharan trading network. By trading directly with Mali’s coastal vassals by sea, Europeans reduced transportation costs and circumvented Arab/Berber middlemen. This shift weakened trans-Saharan trade, and also Portugal started taking Malian slaves, double devastating the economy of Mali. Mali became a rump Kingdom by the early 15th century.

The Songhai Empire (1430-1591)

Songhai started off as a vassal of Mali, in a trading town called Gao. Eventually, due to Mali’s weakness, the Songhai became richer and more powerful. By 1430, the Songhai regained independence from Mali.

The Songhai conquered territory from Mali, defeated Tuaregs, and incorporated Gao, Timbuktu, and Djenne. Songhai, under the Askia dynasty also changed the farming infrastructure. In the Mali empire, slaves had their own farming plots but were required to allocate a portion of their produce to the King. In Songhai, they switched to a slave plantation system, where villages had to meet annual quotas.

The Songhai also controlled the dwindling Trans-Saharan trade, trading gold, kola, grain and slaves with the Arabs and Berbers, who provided salt, copper, and manufactured goods from the Mediterranean Coast.

Unfortunately, Songhai was also suffering from the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. Europeans worked with coastal Africans who hated being a vassal of Songhai. Europeans exchanged rum, guns, and South American foods for African slave captives. The Trans-Atlantic slave trade drained manpower from Songhai so badly that by the end of the 16th century, Moroccans came in again and destroyed the Songhai empire in the Battle of Tondibi. The gold cities of Timbuktu, Gao and Jenne now belonged to Morocco.

Conclusion

I hope this article cleared up some common misconceptions. The Mandinka Black Africans and Songhai developed a decent pre-industrial civilization. You also now see the differences between American and African slavery, and you know that the Saharan Desert didn’t prevent trade between the North and Sub-Saharan Africans. With the Great West African Empires now destroyed, we’ll discuss the aftermath and French colonialism next time. Click here for part 2!

I'm really enjoying this series. Two thoughts:

1) The cross Sahara trade in salt, gold and slaves was pretty old. Weren't the Garamintians running it when the Romans took over.

2) Have you read Shadow Empires about the political structures that form outside empires that mirror them in some aspects? For example, the shadow empires in China's west that were bought off by the Chinese emperors. In some ways our modern empires - the West, the USSR, China - had shadow empires in Africa. It's hard not to see parallels between the Romans treating with Germanic tribes or ancient China buying tribal loyalty by providing luxury goods and the modern IMF and other organizations sending food aid, weapons, debt relief and the like to polities in modern Africa. It's a very interesting book.