The Remastered History of Nigeria Part II: Medieval Northern Nigeria, Islam & Trans-Saharan Trade

Islamic trade, Rising Literacy, Slave raids, & Imperial Rivalries

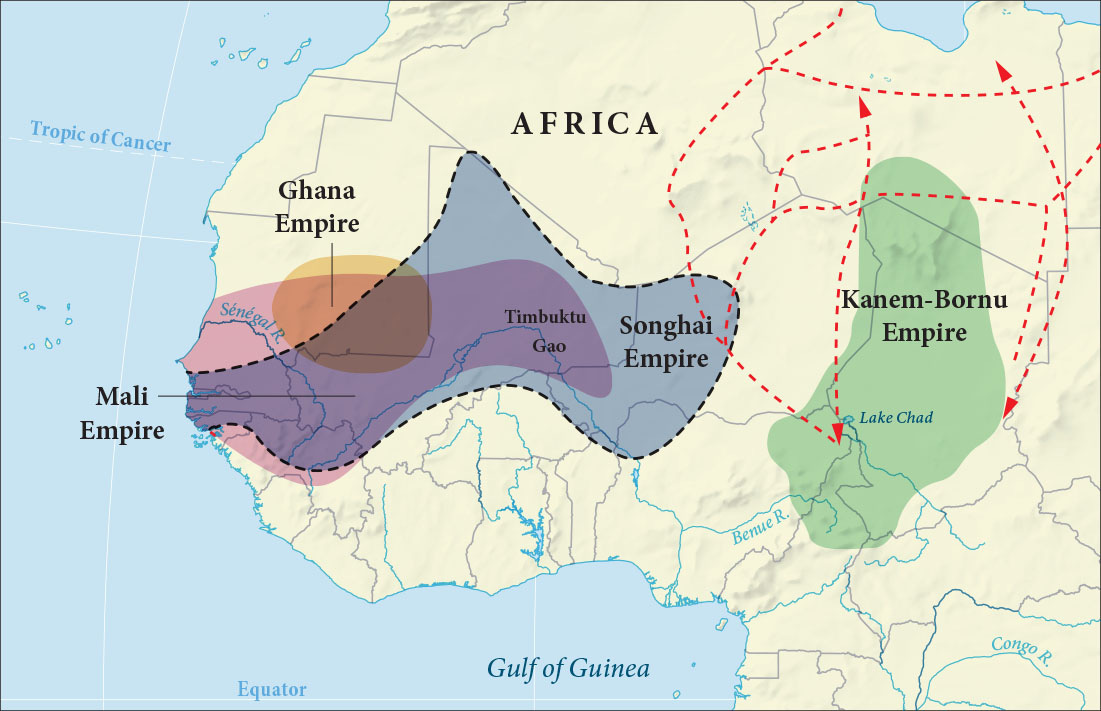

In Part I of Nigeria, we surveyed modern Nigeria and traced its roots back to ancient cultures such as the Nok civilization (as early as 1000 BC). By the 11th century AD, political entities had begun to emerge: Kanem-Bornu and the Hausa city-states in the north, and the Yoruba-Ife, Edo-Benin, and Igbo-Nri polities in the south. Until this point, none of these societies had adopted Islam or Christianity.

12th–13th Century: Kanem-Bornu and Hausaland

In both Kanem-Bornu and Hausaland, the foundations of state power rested on a blend of agriculture, metalworking, and slave-based economies. Gold dust, cloth, salt, and slaves served as key currencies.

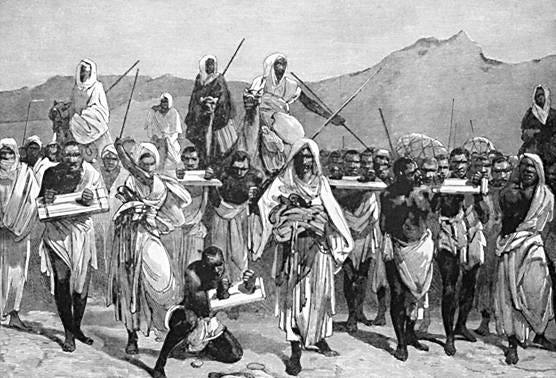

Slaves were not only traded with North African markets but were also central to the domestic economy—serving as domestic servants, agricultural serfs, royal guards, and political tribute. Most commoners were subsistence farmers or artisans, while ruling elites focused on military expansion and regional control.

Kanem-Bornu began as a loose coalition of peoples around Lake Chad, including the Kanuri, Zaghawa, and Tubu. In the 11th century AD, the Sayfawa Dynasty, led by Mai (King) Hummai and his Muslim faction, seized control — suppressing traditional African cults, strengthening ties with the Islamic world, promoting Islamic law and education, and adopting Arabic as the language of record-keeping. This evolved the empire into a confederacy of semi-autonomous chiefdoms, held together by tributary relations & conquest.

Official chronicles such as the Diwan (or Girgam, “The King’s Chronicle”) replaced oral storytelling, and scholars from Kairouan (Tunisia) and Cairo (Egypt) migrated south, deepening Kanem’s Islamic ties.

Under Mai Dunama Dibalemi in the early 13th century, Kanem reached the zenith —expanding across modern-day Chad, northeast Nigeria, Niger, and northern Cameroon and capturing oases like Kawar (a gateway to salt mines). Dunama also launched raids as far north as Waddan in modern day southern Libya.

By conquering parts of southern Libya, Kanem gained control of Fezzan temporarily—a key gateway to North Africa. This trade corridor allowed Kanem to funnel Black slaves, seized through jihad against the Tubu or Bulala peoples or purchased from Mali-Songhai caravans, into North African slave markets in Tripoli or Cairo.

Dunama also forcibly dismantled local African cults like the Mune, and took three pilgrimages to Mecca, dying during his last voyage.

The Sayfawa Dynasty, though long-lasting, was far from stable. By the mid-13th century, Kanem faced dynastic infighting between the Kaday and Bir factions. These crises often turned violent: Mai Kaday and Mai Ibrahim Nikale were both assassinated by their own vassals, reflecting the fragile grip of the central authority.

Despite the instability, Kanem’s armies pushed south, introducing Islam to Hausa city-states like Kano, where it began to take root among urban elites.

14th Century: Kanem Descends, Hausa Rises

Rival Factions & External Threats in Kanem

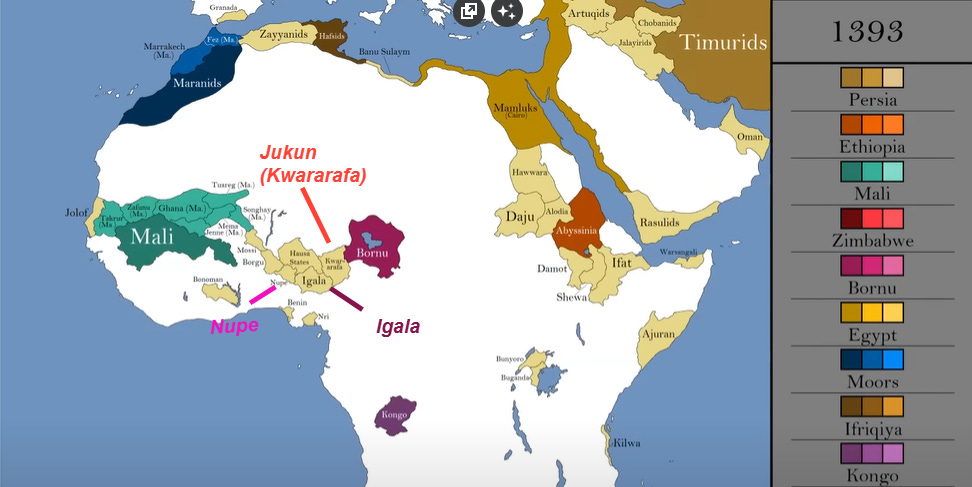

Looking below, you’ll see that the Kanem state dissolved into Bornu.

Following brief stability under Mai Salmana in the early 1300s, the Sayfawa Dynasty descended into a succession crisis between the Idrisid and Dawudid factions. From 1359 to 1383, this internal strife paralyzed the empire.

Amid this chaos, an external threat emerged: the Bulala, an eastern rival ethnic group. Their devastating campaigns killed five of Kanem’s seven kings in a single generation and conquered the trans-Saharan trade routes, the lifeblood of Kanem’s economy.

In defeat, the Sayfawa royal family fled westward and established their empire in Bornu.

Hausaland Ascends: Trade, Slavery, Specialization, and Islam

As Kanem declined, Hausaland rose. Much of what we know about early Hausaland comes from the Katsina, Gobir, & Kano Chronicle, a rich blend of myth and history that traces the rise of the Hausa kingdoms and their political traditions.

Each of the Hausa Bakwai (The Seven True Hausa states) had a distinct economic or political specialty:

Rano and Kano — “Chiefs of Indigo”: Known for their cotton textiles and indigo dye production

Katsina and Daura —“Chiefs of the Market”: Served as entrepôts for caravans from North Africa

Gobir — “Chief of War”: Positioned in the west, it frequently clashed with rival Kings and raided other states for slaves.

Zaria (Zazzau) “Chief of Slaves”: Conducted southern slave raids to supply North African Arab-Berber markets.

Biram – “Chief of Ceremonies”: Held symbolic importance in Hausa traditions and rituals.

Arab chroniclers like Ibn Battuta and his student al-Maqrīzī described Hausa and Kanem-Bornu’s major exports:

In exchange, they imported:

The Trans-Saharan Slave Trade

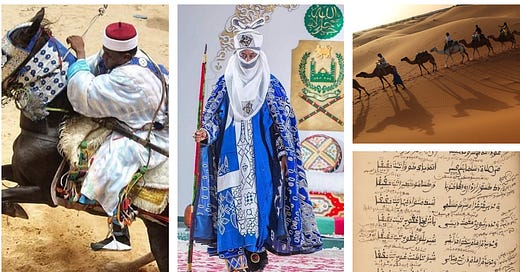

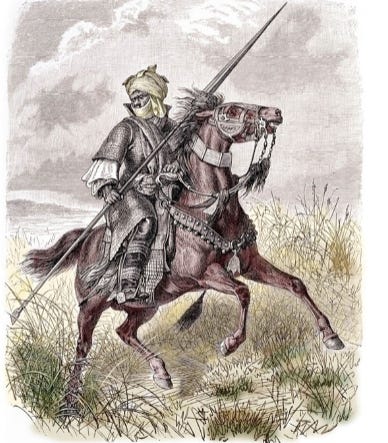

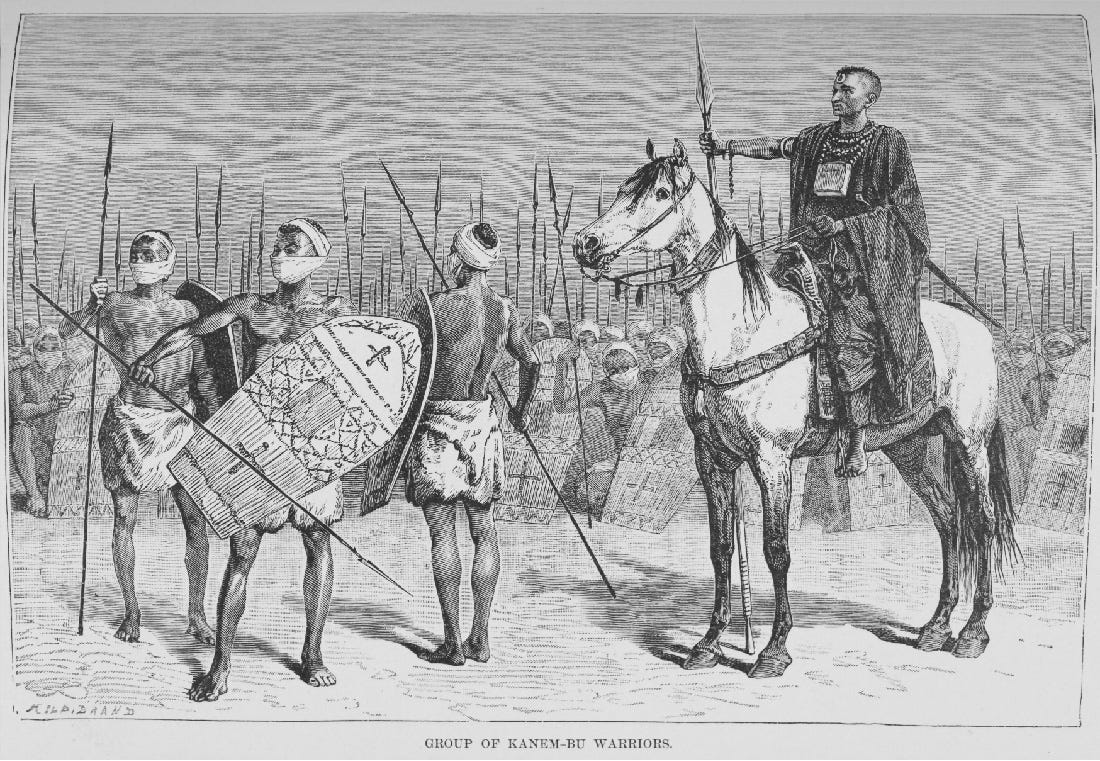

To supply this slave trade, Kanem & Hausaland regularly raided non-Muslim groups around them. Horses, in particular, became central to the empire’s military strength and elite culture.

The 14th century marked the beginning of a "golden age" for the trans-Saharan slave trade, which peaked between the 14th and 16th centuries. Mamluk Egypt and North African Berber dynasties depended heavily on West African gold—especially from the Mali Empire—to mint currency, and on enslaved Black Africans for labor in agriculture, domestic service, and military roles.

To meet this demand, a vast and deadly trade system evolved. Slaves were captured in frontier wars or sold through tribute. Caravans shifted from donkeys to camels, enabling longer desert crossings with fewer stops for food or water. A full Saharan crossing could take up to 80 days, with high risks from extreme heat, water scarcity, banditry, disease, or starvation.

Though exact figures are debated, estimates suggest that between 2.5 to 5 million Africans were trafficked through the trans-Saharan slave trade between 650 AD and 1600 AD.

While Kanem-Bornu & Hausaland were key players in the trans-Saharan slave trade, they were also victims of it. Arab-Berber and Tuareg raiders sometimes targeted Kanem and Hausaland for slaves. In the late 1300s, Mai Idris (1389–1421) wrote to the Mamluks of Egypt, complaining that Arab raiders were abducting his people.

The Spread of Islam

This era also saw the gradual spread of Islam in Hausaland, both from trade with the Arabs, Berbers, and Tuaregs and also through migrants from the Mali Empire like:

Malinke merchants & clerics from Mali

Fulani pastoralists and scholars who brought Islamic education & reform

In 1370, Sarki (King) Yaji I of Kano became the first known Muslim Hausa ruler. But conversion remained shallow at first—limited to urban elites and merchant families, while most of the rural population continued to follow the Bori cult and other spirit-based traditions.

Hausa rivalries continued, despite shared religion & language. For example, in the late 1300s, the Hausa King of Kano killed the Hausa King of Zaria, showing how military competition and slave raiding remained central to Hausa politics, even as Islam spread.

While Kanem declined and Hausaland rose in the 14th century, new powers emerged further south in what is now Middle Belt Nigeria.

Middlebelt Nigeria: Borgu, Nupe, Jukun, & Igala

Known for their cavalry and decentralized structure, the Borgu states would later play key roles in regional trade and warfare.

By the 1380s and 1390s, Hausa and Kanem sources begin to mention additional rising kingdoms. If you look at the map below you will see three new states: Nupe, Jukun, and Igala.

The Nupe Kingdom emerged along the middle Niger.

The Igala Kingdom, emerged near the Niger-Benue confluence.

And most notably, the Jukun Kingdom, known to the Hausa as Kwararafa (Kororofa).

These Middle Belt states maintained indigenous spiritual traditions and resisted Islam well into the 19th century, even as their northern neighbors converted. All of them were raided by Bornu & Hausaland for slaves.

Conflict and Trade Between Jukun and Kano

The Jukun Kingdom became a military rival to the northern Hausa states. The Hausa Kano state, expanding southward, attempted to subjugate the Jukun but failed to do so. After several clashes, the Jukun delivered 100 slaves as a diplomatic gesture but remained politically independent.

Eventually, they became trading partners, Jukun traders sold slaves to the Hausa city-states in exchange for horses, which was basically the “combat drone” of the 14th century in pre-colonial northern Nigeria.

15th Century

Slaves in Society

Besides selling slaves, Kanem-Bornu and Hausaland used slaves for statecraft, military, and family building. Here’s some examples:

Eunuchs—these slaves were as high-ranking advisers since they could not bear kin to establish rival dynasties

Concubines — used to expand royal households, particularly under rulers like Sarkin Kano Muhammad Rumfa (r. 1463–1499)

Corvée labor—forced labor for farming and ore mining—became widespread in both states.

Islamic Institutions

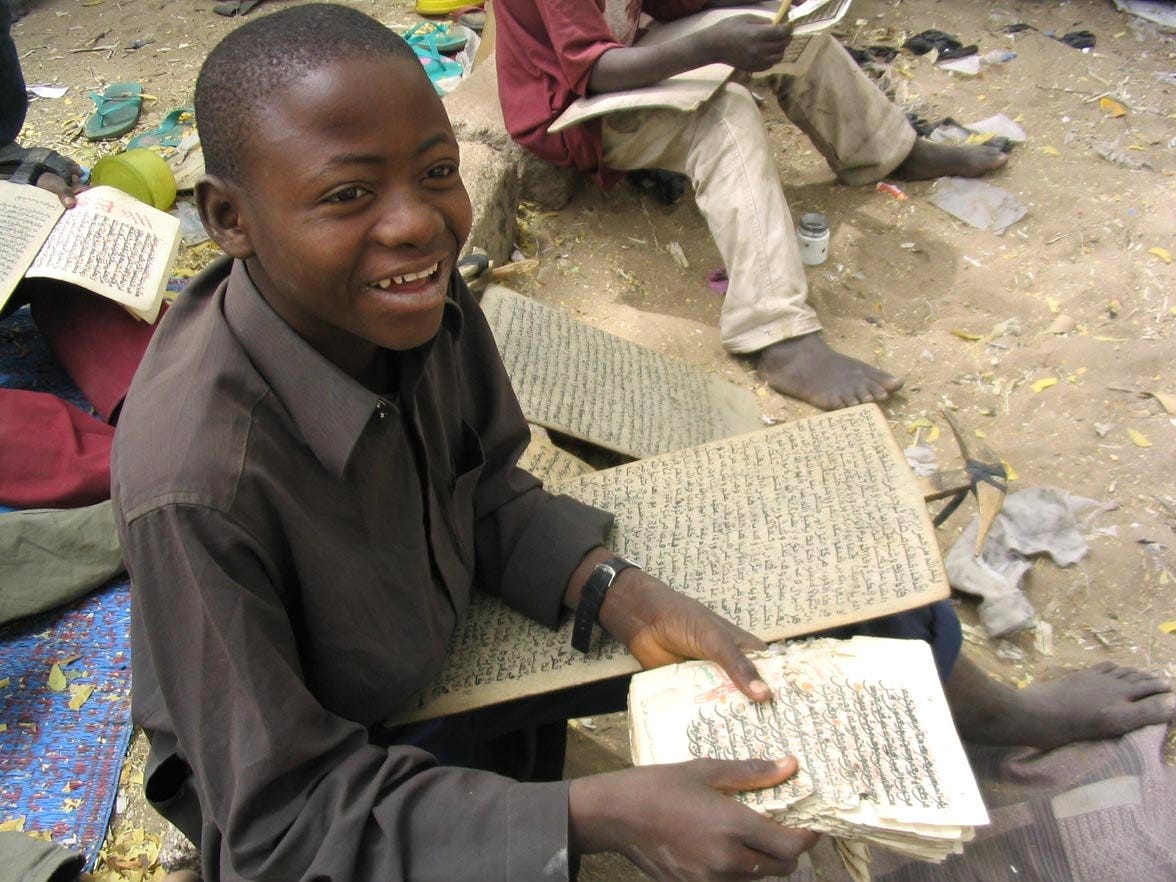

By this period, Islam had moved beyond surface-level rituals. Hausa & Bornu Kings began to legitimize their rule through Islamic law, scholars, and pilgrimage. Arab scholars and Malian clerics established basic Qur’anic schools—called Kutab in Arabic or Makarantan Allo in Hausa—where elite children learned to read Arabic and recite scripture.

Over time, madrasas (Arabic) or Makarantan Ilimi (Hausa) emerged to offer more advanced instruction in law, grammar, and theology. These schools produced a growing class of ulama—Islamic scholars and legal experts—who began to shape court policy and local jurisprudence. (Note: literacy and Islamic education remained largely restricted to elite families).

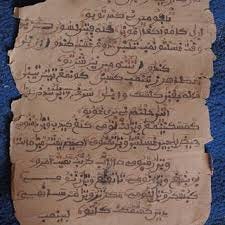

The Ajami Revolution

One of the most important innovations of this era was the development of Ajami— Arabic script adapted to write Hausa, Kanuri, and other local languages. (Ajami means foreign script in Arabic).

This transformed state governance and trade:

Bureaucrats could maintain tax records, issue decrees, and resolve disputes more efficiently.

Commercial contracts and legal rulings were increasingly formalized

Bornu in the 15th Century

After decades of civil war and Bulala invasions, Bornu began to recover under Bir ibn Idris (c. 1389–1421), who finally defeated the Bulala and reclaimed lost territory. But while the throne survived, its power had eroded.

Real power now rested in the hands of military officials, especially:

These generals manipulated the royal succession, playing the Idrisid and Dawudid dynastic factions against each other. From 1440 to 1460, Bornu was effectively ruled by its military commanders, reducing the Mai (king) to a ceremonial figurehead.

Amid the chaos, the Idrisid faction gradually gained the upper hand. Around 1459, Ali Ghadjideni defeated the final Dawudid rival. Although customary collateral succession forced him to wait behind older relatives, he eventually took the throne in 1465.

His reign marked a political and institutional turning point:

He founded Gazargamo, which became Bornu’s new capital and political center for centuries.

He restored dynastic stability and his reforms were consolidated by his son, Idris Katakarmabe, and grandson, Muhammad ibn Idris, ending nearly a century of dynastic crisis.

Hausaland in the 15th Century

The 15th century was a period of both expansion and internal strife in Hausaland.

On the positive side, trade expanded significantly. A major route opened from Bornu through Hausaland to Gonja (in modern-day northern Ghana), facilitating the exchange of camels, salt, kola nuts, and eunuchs. The growing regional and trans-Saharan economy made cities like Kano, Katsina, and Zaria commercial hubs.

But political unity remained elusive. Hausa city-states frequently fought one another:

In the 1400s, Kano lost a war to Zaria, weakening its regional standing.

Kano and Katsina entered a century-long rivalry, marked by battles, raids, and shifting alliances.

Zamfara and Gobir, positioned in the western frontier, suffered repeated Tuareg slave raids.

Meanwhile, with Bornu’s resurgence under stronger leadership, it subordinated Kano, which paid an annual tribute of 100 slaves to Bornu—a clear signal of Bornu’s regional dominance.

The turning point came with the reign of Sarkin Kano Muhammad Rumfa (1463–1499), who ushered in a “golden age” of political, commercial, and religious reform. He constructed new city-gates, appointed Arab-Berber advisors, and founded the Kurmi Market, which became the city’s commercial heart and a hub for regional and trans-Saharan trade.

Al-Maghīlī, a Maghribi scholar, advised Rumfa to end pre-Islamic rituals and symbols. Rumfa's destruction of sacred trees and suppression of local cults signaled Kano’s turn toward Islamic orthodoxy, which helped attract more Muslim scholars, merchants, and travelers. Seeing the success, Katsina followed a similar path. Under Ibrahim Sura (r. 1493–1499), Katsina became a religious center, constructing the Gobarau Mosque and enforcing Islamic discipline—even jailing those who refused to pray. During this period, Sura also corresponded with Egyptian scholars like al-Suyuti, seeking religious guidance, which further enhanced Katsina's legitimacy in the Islamic world.

16th Century

Warfare and Rivalry

The 16th century in Northern and Middle Belt Nigeria was marked by near-constant warfare, as states and empires raided one another for slaves to supply the trans-Saharan trade. Expansion, rebellion, and retaliation defined the era.

Songhai & The Breakaway Kebbi: In the late 15th century, Sunni Ali of Songhai crushed the weakened Mali Empire, capturing Timbuktu and Djenné, vital trans-Saharan trade hubs. In the 1500s, the Songhai empire expanded influence even up to modern-day Northwest Nigeria.

However, around 1517 Kebbi, led by Muhammadu Kanta, seceded from Songhai. In the 1550s it defeated Bornu and briefly controlled sections of Hausaland. After Kanta’s death, Kebbi’s influence faded.

Bornu: Bornu in the 1500s started off strong. It attacked the Hausa Kano state and forced the King to submit and supply 100 slaves to Bornu per year. However, internal problems in Bornu soon surfaced: rebellions, dynastic instability, slave raids from Jukun, and famine. Eventually Kano left Bornu’s vassalage and raided Bornu. Kano deliberately seized Bornu’s horses and slaves. Bornu was weakened and almost devolved to a failed state.

Hausaland: After raiding Bornu, Kano was able to make other Hausa states like Zaria and Katsina tributary states (temporarily). But Katsina broke free and Kano & Katsina fought a series of bloody wars and famine, locked in military stalemate throughout much of the century. As these Hausa states fought, Jukun exploited the situation and raided both Kano & Katsina for slaves.

Bornu’s Comeback

Mai Idris Aluma (r. 1571–1603) ushered in a powerful revival of Bornu, reestablishing it as one of the dominant empires in West Africa. His reign combined military expansion and strategic diplomacy.

Thanks to slave trading with North Africa from earlier times, Kanem Bornu had diplomatic ties with Ottoman controlled Tripoli. After performing the Hajj via Ottoman Mecca, he established correspondence with the Sultan in Istanbul, Murad III, arranging the exchange of Black African slaves for Turkish firearms, armor, and military advisors. Bornu was considered among the 1st Sub-Saharan African rulers to use guns in warfare, giving Bornu a technological advantage over rival states.

With firearms, Aluma launched campaigns across the Sahel and Sahara:

While all this was happening, the Songhay empire’s influence in Northeast Nigeria ended, as the Moroccans (Saadi dynasty) destroyed the Songhay Empire.

Concluding Thoughts

Writing this history reminds me that there’s a difference between history (raw facts & sequence of events) and historiography (the narrative we build to give meaning to those events, and which facts we choose to speak of).

This period in Nigerian history is incredibly complex and largely unknown to most people. Like all complex histories, it’s easy to spin it in many different directions.

If I were more biased, I could frame this as a story of cultural enrichment, Islamic connectivity, and the rise of African literacy. Northern Nigeria in the 15th and 16th centuries was, in many ways, more advanced than the South: it had access to firearms, Arabic and Ajami literacy, elite education, and even diplomatic relations with the Ottoman Empire. Mai Idris Aluma’s correspondence with Istanbul and his use of Ottoman guns shows how religion, knowledge, and trade traveled together.

If someone argued that “Africans didn’t have writing before Europeans arrived”, while true for some African regions, Northern Nigeria was not one of them. The existence of Islamic law courts, royal correspondence, tax records, and Qur’anic schooling in Kanem-Bornu or Hausaland proves otherwise. Also, if someone claimed “Sub-Saharan Africa had no contact with the outside world until Europeans”. One could mention Kanem Bornu’s Idris Aloma’s correspondence with Murad III of Ottoman Turkey.

But there’s another narrative — that one shouldn’t romanticize the past. This era was also defined by dynastic violence, state failure and endemic raiding. Many of Nigeria’s modern challenges—ethnic conflict, weak institutions, military juntas, coups. and regional fragmentation—predate colonialism. From Kanem’s succession crises & military rule, to Kano and Katsina’s endless wars, to the Kebbi-Bornu battles and Jukun slave raids, the 14th to 16th centuries were marked by instability and violence long before European conquest. These weren’t peaceful empires — they were brutal, contested, and unstable.

Another angle is technological lag: This area of Sub-Saharan Africa lacked firearms until it connected with external powers. Only after Kanem-Bornu received Ottoman muskets did it regain regional dominance over other Sub-Saharan African rivals. Even Songhai, which had defeated Mali, one of the most famous and powerful West Africa Kingdoms, was crushed by Morocco’s gunpowder army in the Battle of Tondibi in 1591—highlighting the sheer technological gap between the two. And even Morocco -technologically ahead of West Africa — was still behind Europe. It was easier for the Moroccan Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur to destroy the Songhai empire in West Africa than to reconquer Ceuta & Melilla from Spain & Portugal (which they took in the 15th century and still hold today!). This shows that even in the 16th century, Sub-Saharan Africa was behind North Africa, and North Africa was arguably behind Europe.

Lastly, this history raises a counterfactual: What if Europeans had never taken slaves from Africa? While Southern Nigerian coasts were changed by the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the Northern Nigeria remained largely untouched by Europeans until colonialism due to disease—Africa was, after all, known as the ‘White Man’s Grave” until the 1850s. Yet even without the contact with Europeans until the 19th century, the northern interior tells a sobering story: African Empires raiding and enslaving rival Empires, selling captives to Arabs, Tuaregs, and Berbers—entirely without any European involvement at the time.

And that’s the point: all of these interpretations are defensible: Literacy and bondage, brilliance and brutality, diplomacy and disintegration. The real challenge is not choosing one narrative, but holding them all together—and learning to live with that complexity.

Next time, we’ll continue from 17th-century Northern Nigeria through the era of colonial conquest.

Sources

General history of Africa, IV: Africa from the twelfth to the sixteenth century

General History of Africa: V: Africa from 16th to 18th Century by B.A. OGOT

The Emirates of Northern Nigeria: A Preliminary Survey of Their Historical Traditions by S.J. Hogben and A.H.M. Kirk-Greene

Britannia

History of Borgu

Oxford Research Encyclopedia: The Kanem and Borno Sultanates (11th–19th Centuries)

Yaw, Your history is fine! I note two things: The fate of empires is especially interesting because of the very frequent references Richard Wolff makes to the American Empire as one in decline. What happens when power fades and is lost? The other thing is the use of Starlink by insurgents in the Sahel and its overwhelming effect on the (military) rulers of the countries. I wonder if the borders established by colonial powers will be in place in the next century. African societies may have entirely new borders in the future, with political entities shifting as they have before the 19th Century.

Fascinating! Nothing I love more than historical contexts.