The Economic & Geopolitical History of Tunisia, Part 2: Banker Imperialism, French Rule, and the Road to Independence

Debt Trap Diplomacy requires two ingredients: greedy financiers and corrupt, short-sighted rulers. That sums up how Tunisia was colonized

Tunisia's long history is a tale of shifting rulers—Amazigh tribes, Phoenician traders, Roman legions, Arabian Caliphates, and Ottoman governors—all leaving their mark before the modern era. Read Part I to learn more.

By the time of Arab rule, many Berbers identified as Arab-Berbers. Later by the time of Ottoman Rule, Tunisia functioned as an autonomous province, governing itself while paying token allegiance to the Sultan in Istanbul. Unlike Algeria, which had a direct Ottoman governor, Tunisia maintained its own administration under local rulers.

During this period, Tunisia was an equal-opportunity enslaver, capturing both Sub-Saharan Africans (through trade) and Europeans (by piracy). Today, I’ll dive into Tunisia’s last ruling dynasty before French colonization, the Husainid dynasty. This dynasty was founded by Al-Husayn ibn Ali, a Kouloughli — a man of mixed North African and a Turkish descent. Al-Husayn rose through the military ranks to become the Bey (Governor) of Tunis, eventually establishing a hereditary monarchy.

Husainid Dynasty

Mamluk Rule and Taxation Troubles

Like the Ottoman Turks, the Husainid rulers depended on Mamluks—elite former slaves trained as military and administrative leaders—to govern the province.

The Husainids ruled through a decentralized tax system, relying on over 2,000 tribal sheikhs to collect revenue. However, widespread tax evasion by these local leaders drained state finances, forcing the Beys of Tunis to turn to piracy and the European slave trade to fill the treasury. Tunisian corsairs raided Mediterranean waters, seizing European ships and capturing sailors for ransom or enslavement.

Tunisia’s autonomy did not guarantee stability. The Beys constantly navigated conflicts with foreign powers, particularly Algiers and Venice. In 1756, the Dey of Algiers attempted to assert control over Tunis, leading to a brief power struggle. Meanwhile, between 1784 and 1786, Venice retaliated against Tunisian piracy by bombarding coastal cities, crippling trade and exposing the risks of state-sponsored corsair activities.

Early U.S. Struggles with Barbary Piracy

After the American Revolution, young United States faced a new challenge on the high seas—the loss of British naval protection left its merchant ships defenseless in Mediterranean trade. The Beys/Deys of Tunis, Algiers, and Tripoli saw an opportunity, seizing American vessels and enslaving sailors, demanding tribute in exchange for safe passage.

Desperate to protect its sailors, Washington's administration reluctantly paid tribute, following the European model of appeasement. But when John Adams took office, the U.S. sought a more formal arrangement, signing the 1797 Treaty of Peace and Friendship with Tunis, agreeing to regular payments in exchange for safe passage.

Tunis upheld its treaty, but Tripoli demanded more tribute—a demand President Thomas Jefferson refused, signaling an end to American appeasement. When Tripoli declared war, the U.S. Navy struck back in what became the First Barbary War (1801–1805), immortalized in the Marine Corps hymn: 'To the shores of Tripoli.'

By 1815, American patience had run out. After years of continued attacks & enslavement, President James Madison sent the U.S. Navy to crush Algiers, launching the Second Barbary War. The swift American victory forced Algiers to end piracy, while Tunis and Tripoli were pressured into signing new treaties guaranteeing free passage for U.S. ships.

With the Barbary threat eliminated, European powers quickly followed America’s lead. After the Napoleonic Wars, Britain and France pressured Tunisia to end Christian slavery, forcing it to sign treaties opening Mediterranean trade to European merchants.

With European treaties forcing Tunisia to abandon the Mediterranean slave trade, the Beys turned increasingly to the Trans-Saharan slave trade to sustain their economy. They sourced slaves from the Sokoto Caliphate—which controlled much of present-day northern Nigeria, southern Niger, and northern Cameroon—as well as from Tuareg nomads who served as intermediaries between North & Sub-Saharan Africa. The Black Africans served as farmers, cooks, nannies, gardeners, and household attendants. However, unlike in the Americas—where enslaved populations grew through birth—many male captives in Tunisia were forcibly castrated and made eunuchs, preventing an enslaved class from forming over generations.

Tunis and Algiers: A Power Struggle

For decades, the Dey (Leader) of Algiers tried to turn Tunis into a vassal state, demanding tribute and military support. In 1807, Hammuda Bey of Tunis refused, triggering an Algerian invasion of western Tunisia. The Tunisian army repelled the assault, preserving its autonomy. But by the 1830s, Algiers fell to French colonial rule—marking a shift in North Africa’s balance of power.

Tunisia’s Financial Collapse (1837-1868): Debt, Corruption, & Foreign Control

With Algiers under French rule and European powers expanding their influence in North Africa, Tunisia found itself caught in a four-way tug-of-war between Ottoman Turkey, France, the UK and Italy. For example:

Ottoman Turkish Influence: Tunisia was still nominally under Ottoman suzerainty, and in 1854, Sultan Abdülmecid I ordered Tunisia to send 4,000 troops to fight in the Crimean War against Russia. The war had little relevance to Tunisia; the forced deployment drained its military resources.

French Influence: Even before colonialism, French merchants were settling in Tunisia under the Tunisian Bey’s permission. France pressured Tunisia to end its tribute payments to the Turkish Sultan. Also, in 1857, the Batto Sfez Affair ignited a crisis in Tunis. A Jewish cart driver, Batto Sfez, was beheaded for insulting Islam. His severed head was kicked like a soccer ball in the streets, sparking outrage among the Jews and Europeans that lived in Tunisia. Under pressure from Napoleon III, Bey Mohammed II issued the Fundamental Pact of 1857, granting legal equality to all religions. Then in 1861, the Tunisians wrote the 1st written constitution in the Arab world, separating executive, legislative, and judiciary powers and strengthened foreign investment rights to Europeans.

British Influence: In 1863, UK and Tunisia ratified an agreement that Tunisia will never take black or white slaves again. There was also a small Maltese community in Tunisia that was under British protection.

Italian influence: Before colonialism, Bey Mustafa also allowed Italians to migrate to bring skilled labor. When Italians took over farm land, mechanization reduced the need for peasant farmers, leading to mass evictions of Tunisian peasants and skyrocketing rural unemployment. By 1880s, there were 10K Italians and 4K French settlers in Tunisia.

To avoid European or Turkish overlordship, Tunis embarked on a modernization campaign that was a financial catastrophe. Tunisia’s descent into financial ruin was driven by mismanagement and corruption. The crisis unfolded under Bey Ahmed I ibn Mustafa (1837-1855) and his Prime Minister and Treasurer, Mustafa Khaznadar (1837-1873)—a Greek-born Turkish bureaucrat who embezzled millions, driving Tunisia into bankruptcy by 1868.

Under the Bey and Mustafa, Tunisia made a public debt office and borrowed large sums from wealthy Tunisian locals and European expats to fund military and industrialization projects, including linen factories.

Funds also went to education, with institutions like Zitouna Mosque School thriving.

Chickens came home to Roost

Unfortunately, the public works program was a fiasco — factories crumbled, military projects collapsed, and unfinished palaces drained the budget. Tunisia’s debt shot up 60% from 1859-1862, with much of the funds embezzled to build luxurious homes in Britain and France. The government was printing money to directly buy from the treasury, causing the Tunisian currency (Tunisian rial, later the piastre) to depreciate. This caused inflation, made imports more expensive, and exporters received less money for selling goods (like grain).

The Beylicate of Tunisia tried to sell more teskeres (bonds) to local investors but they refused to buy more bonds, leading Tunisia to seek out foreign loans.

Tunisia’s 1863 Loan

By 1863, Tunisia’s currency was functionally useless, no investor worth their salt wanted a bond denominated in Tunisian Riyal. Desperate, the Bey’s government borrowed in foreign currency for the first time, going to French bankers to issue bonds on the Paris Stock Exchange(Bourse de Paris).

Tunisia raised a 15-year term, 30M French franc loan at a 7% interest rate. PM Khaznadar and his clique ended up stealing substantial sums of the money and collected kickbacks from contractors. Many of the state-led projects failed. So to cover costs, the Beylicate government decided to double taxes (mejba) causing the Arab-Berber tribes to rebel in 1864.

The 1864 Tax Revolt and European Intervention

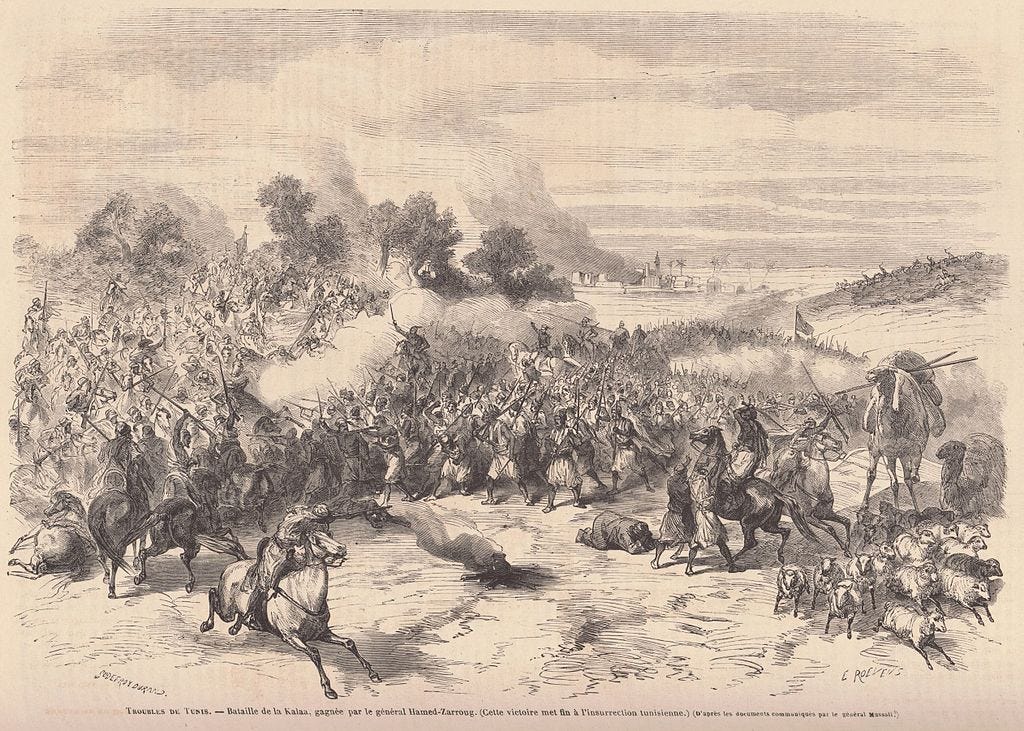

The Arab-Berber tribes rebelled against tax hikes. To gain influence in Tunisia, France, Britain, Italy, and Ottoman Turkey sent warships to intimate Arab-Berber rebels. But, the Arab-Berber tribes still fought. Though the Bey eventually repealed the tax, he later launched a brutal crackdown with Ottoman support, executing rebel leaders and confiscating 23M Tunisian piastres from rural communities.

Tunisia’s Second Debt Disaster (1865): A New, Even Worse Loan

It’s 1865, you can’t raise taxes anymore from the population you just stole from. You are in a financial crisis, your projects failed, so what does Khaznadar do? He goes to Paris for another loan. This time he raised 20M at 9.2% at 15 year term.

Since Tunisia was seen as a risky investment, the Paris banks made it a “tied loan” so the banks could benefit. The French banks made Tunisia buy two old worthless ships for 250K francs, 100 defective guns for 1M francs (actual value: 200k), and Erlanger Bank took control of a linen factory in Tebourba, Tunisia.

Things went from bad to worse in 1866-1867. There were bad harvests, famine, and a cholera outbreak, killing 20K Tunisians nationwide due to food shortages and poor healthcare funding. As Tunisian Arabs were dying, French businessmen scooped up the land at a discount to make more grapes and olive oil.

Tunisia was nearly a failed state. European bankers were now hesitant to lend internationally since Mexico just defaulted on its debt to French bankers.

The Bey of Tunis wanted to raise 100M francs, but that failed. He was only able to raise 9M francs at a 15% interest rate. In 1867, Tunisia defaulted.

The International Financial Commission (1869): The “Proto-IMF”

By 1869, Tunisia’s foreign creditors —French, British, and Italian bankers & controllers created the International Financial Commission (IFC)—essentially a proto-IMF—to oversee Tunisia’s economy and ensure debt repayment. The IFC took control of Tunisia’s tax revenue, approved/denied any new loans, restructured & recorded Tunisia’s total debt, and put European financial controllers in charge, with France having the most influence.

The interests of the bankers were not the same interests as the country. The Bankers wanted Tunisia to pay its periodic interest payments, which diverted Tunisia’s ability to spend on public works (manufacturing, railways, paved roads, or sanitation), but even then, the IFC couldn’t fix Tunisia’s debt issue. Why? In the 1870s, the first global depression happened. In fact, the 1870s was the original great depression before the 1920s one, so now economic historians call the 1870s global depression as the Long Depression. The global depression was so terrible that Tunisia’s tax revenues couldn’t cover the 125M francs debt.

At this point, Tunisia was barely sovereign. Mustafa Khaznadar was removed as Prime Minister, replaced by his son-in-law Kheireddine Pasha, a Circassian Mamluk of Abkhaz origin (modern day Georgia), who ruled from 1873 to 1877.

Kheireddine tried fiscal reforms, tried curbing corruption, and tried spending more on education (the new Sadiki College). Unfortunately, the European bankers blocked other reforms and forced others. For example, Tunisia’s grain export trade was monopolized by French & Italian merchants.

By 1877, Kheireddine attempted to push back against European influence, making him unpopular with both France and Tunisian elites. Under French pressure, he resigned and replaced by Mustafa Ben Ismail, a French puppet.

Next year, in the Congress of Berlin in 1878 (not the Berlin Conference!), Britain allowed France to take Tunisia in exchange for French to recognize Britain’s acquisition of Cyprus from Ottoman Turkey. This move infuriated Italy, which had territorial ambitions in Tunisia.

For three years, France needed a pretext to take Tunisia. Tunisia was a loyal pawn, allowing French farmers kick out Tunisians, Tunisians stopped piracy, and stopped slavery, so what pretense did France have to take Tunis?

Well, in April 1881, some Tunisian Arab-Berber tribesmen raided the border across French Algeria killing 6 French solidiers, So France mobilized 24K troops to hunt down the Arab-Berber tribes, crush them, and then occupy the port of Bizerte, setting the stage for colonization.

France made Sadok Bey sign the Bardo Treaty, which made Tunisia a French protectorate.

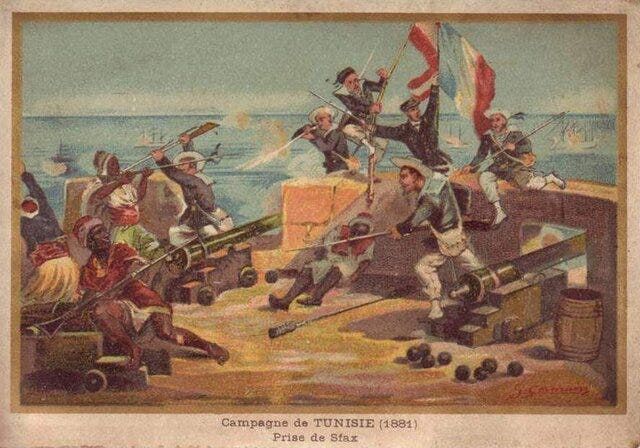

Tribal uprisings broke out, especially in Kairouan and Sfax. France invaded Tunisia, occupied Tunis, bombarded Sfax, and by November Tunis was taken.

French Tunisia (1881-1956)

French Takeover and Early Colonial Rule (1881-1890s)

Under the Al Marsa Convention (1883), Tunisia remained a protectorate, with the Bey as a figurehead, while France controlled finances, foreign affairs, and military bases—notably Bizerte, developed into a major naval port.

Economic Development and European Settlers (1890s-1920s)

Tunisia’s foreign debt was consolidated into a 125-million-franc loan from France, and the International Financial Commission was abolished.

250,000 French settlers arrived, acquiring vast agricultural land and establishing large-scale commercial farming—primarily grape and olive production. They were also blue collar workers, public utilities workers, and shopkeepers.

Phosphate mining became a major industry.

By 1892, French farmers owned 20% of Tunisia’s arable land in the north.

French influence modernized Tunisia’s tax system, roads, railways, ports, schools, hospitals, and sanitation. Over time, Tunisia’s Sharia courts gradually superseded French courts. However, weak tax collection from farmers left Tunisia spending more than it earned. While Tunisian elites gained opportunities, most native Tunisians resented European settlers (French, Italians, Maltese), who enjoyed legal and economic privileges.

Rise of Tunisian Nationalism (1900s-1930s)

French education & culture left indelible marks. It exposed Tunisian elites to European political ideas, including nationalism, modernity, and secularism. The French referred to the educated Arabs as “evolues” (evolved ones).

Early Nationalist Movements

The Young Tunisians (1907-1912), led by Ali Bach Hamba and Bashir Sfar, sought reforms within French rule, blending Islamic and Enlightenment ideals. They published Le Tunisien, appealing to liberal French readers.

They later joined labor disputes, demanding jobs for Tunisians over European settlers. France cracked down on protests in 1912.

Destour Party (1920s-1933)

After WWI, nationalist Tunisians formed the Destour (Constitution) Party, made up of traditional elites (Turks, merchants, professionals) who sought gradual reform while maintaining the monarchy and French ties. France granted Tunisians limited rights in 1922 but refused full equality. France also tried to kill Tunisian nationalism by offering citizenship to the Tunisian elites, but few took it.

The Great Depression (1930s) devastated Tunisia’s economy, as global demand for their grapes and olives declined. This fueled riots and protests. France responded by dissolving the Destour Party in 1933.

Rise of Neo-Destour and Mass Mobilization (1934-1938)

In 1934, Habib Bourguiba, an Arab French-trained lawyer, formed the Neo-Destour Party, which took a more radical, secular, and socialist approach. Unlike the old pro-monarchy Destour Party, Neo-Destour mobilized workers and rural Tunisians against colonial rule.

France cracked down hard, killing 122 Tunisians during protests on April 9, 1938—a day now known as “Martyr’s day”.

Tunisia in WWII: A Turning Point (1940-1945)

In 1940, Nazi Germany occupied France, weakening French control in Tunisia. Mussolini claimed Tunisia as Italian territory, but many Tunisians remained loyal to Free France.

In 1942-43, Tunisia became a major WWII battleground as Allied forces defeated Germany and Italy. The Nazis killed/enslaved Tunisian Jews and freed Bourguiba, but Bourguiba predicted the Fascists would lose and sided with the Allies, negotiating postwar autonomy for Tunisia.

Independence Struggle (1946-1956)

By 1946, France began loosening control, granting Tunisia limited self-rule. France didn’t want to give independence since Europeans were roughly 7% of Tunisia’s population and owned the good land there, but Tunisian nationalism was unstoppable.

Unlike Morocco, where nationalism was led by the Sultan, in Tunisia, Bourguiba’s Neo-Destour Party led the movement, demanding a more rights, and French withdrawal.

Bourguiba led protests and Arab tribes did guerilla fighting, but in 1952, France arrested Bourguiba.

France was losing its ability to retain its colonies since it was fighting to retain Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) and Algeria at the same time.

France just found oil in Algeria and didn’t want to lose Algeria. Tunisia and Morocco weren’t as natural resource endowed, so by 1954, France made the “Declaration of Carthage”, freed Bourguiba, and gave Tunisia autonomy.

Between 1955-1956, a power struggle emerged between Bourguiba and Salah Ben Youssef, his former nationalist ally.

Both were socialists and nationalists, but:

Bourguiba wanted a secular, pro-Western Tunisia, negotiating independence peacefully.

Ben Youssef favored Pan-Arab and Pan-Islamic nationalism, opposing Bourguiba’s pro-Western stance.

Youssef called Bourguiba a traitor for accepting France’s deal. His followers- the Youssefists—resorted to armed violence, leading to crashes with Bourguiba. With French backing, Bourguiba crushed the Youssefists and forced Ben to flee to Egypt in 1956.

Ben Youssef later escaped to Germany but was assassinated in 1961.

Independent Tunisia

Kingdom of Tunisia (1956-1957)

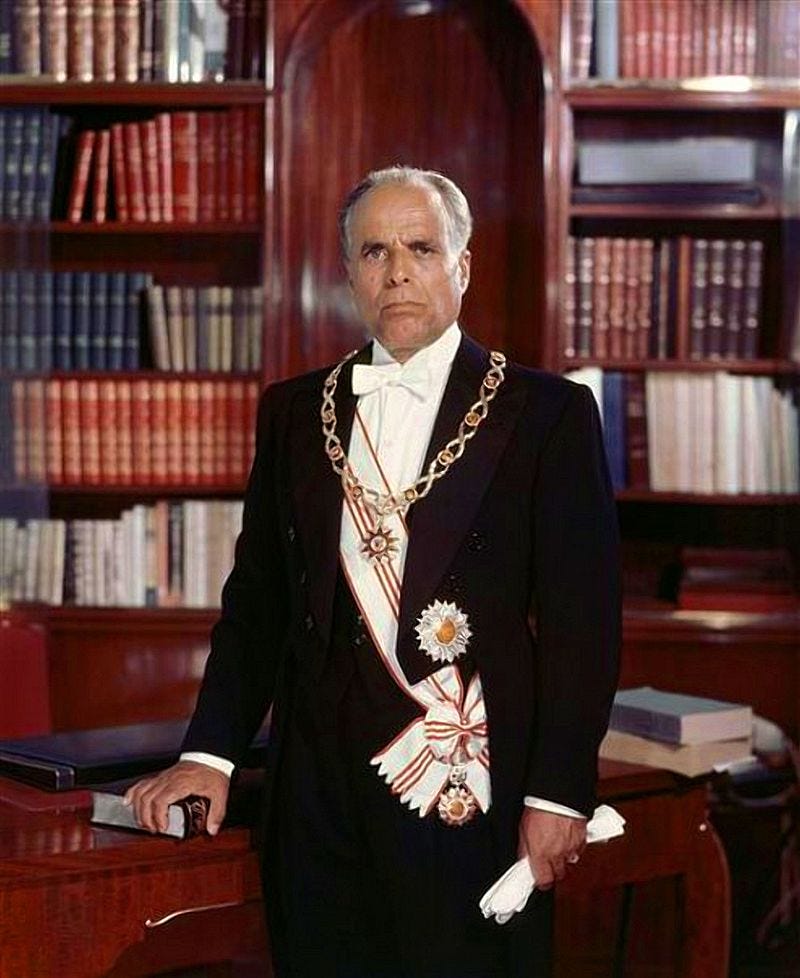

In 1956, France granted full independence to the Kingdoms of Tunisia and Morocco. Tunisia became a constitutional monarchy, with King Al-Amin as a (figure)head of state and Bourguiba as Prime Minister with his Neo-Destour party leading. Islam was (and is) the state religion.

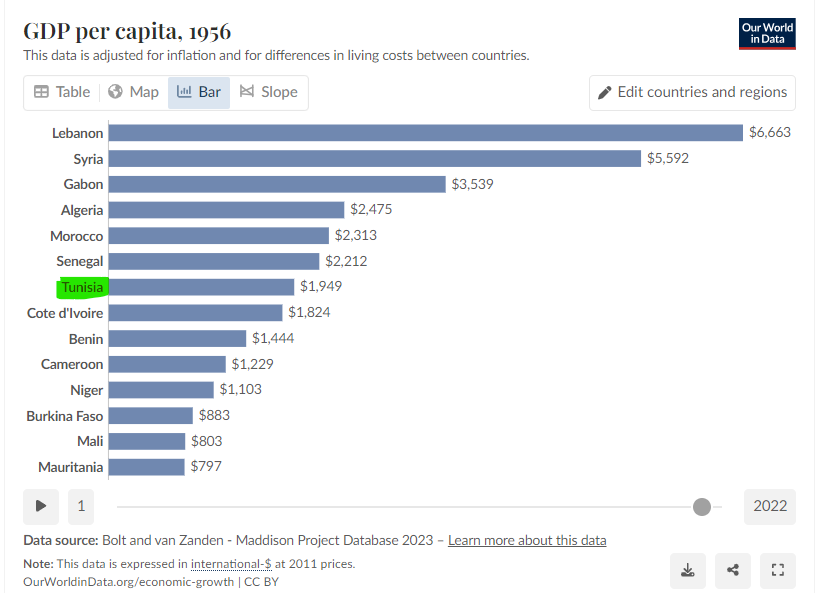

At independence, Tunisia was poorer than Syria, Lebanon Algeria, Morocco, and even Gabon & Senegal, but richer than the majority of Sub-Saharan African countries.

Bourguiba promised Jewish equality, but actions taken by Bourguiba’s party made Jews feel unsafe in Tunisia.

Jewish synagogues, cemeteries and Jewish quarters in Tunisia were destroyed for urban renewal.

Jewish businesses were required to have at least one Muslim partner.

Tunisia used to have over hundred thousand Jews, but by 1956, only 60K were left, leaving to France or Israel.

Bourguiba gradually replaced the French civil service with Tunisians, though he encouraged European settlers to stay and take citizenship—few did, but they kept their land (for awhile). French settlers continued exporting wine, fruit, and vegetables, providing Tunisia with foreign exchange earnings.

Despite independence, France retained control of Bizerte, maintaining a military presence there for a time.

In 1957, Bourguiba and his nationalists abolished the Bey, transforming Tunisia into a republic.

“System? What System? I am the System!” — Bourguiba

Bourguiba felt he had a significant amount of work to do. Like most of Africa (North Africa included!), they were mainly illiterate, where literacy was only extended to the elite at best. Most people learned orally and visually. Male illiteracy was 70% and female illiteracy was 90% at the start of his rule. The economy was mainly agrarian. How did Bourguiba rule? Well find out next time in Part 3!

Concluding Thoughts

French treatment of Tunisia before colonization is a perfect example of debt trap diplomacy. There were two aspects, you need a leader who doesn’t care for his people and only wants to enrich himself (Mustafa Khaznadar) and a power hungry nation (France).

French colonialism varied across regions. Algeria was treated as an extension of France with large European settlements, Tunisia and Morocco remained protectorates with smaller settler communities, while West & Central Africa were governed indirectly through local chiefs.

Very informative, never seen Tunisia under this angle - thank yoou Yaw !!! I have more research to do now !!