Tunisia Part 3: Habib Bourguiba – Founding Father, Secular Strongman, & Arab Maverick

A Story about Autocratic Secularism, Socialist Missteps, and the Rise of Political Islam"

Welcome to Part III of my Tunisia series, where we dive into the legacy of Habib Bourguiba, the founding father of modern Tunisia. This chapter covers his economic gambles, foreign entanglements, and his never-ending war with political Islam.

For context, Part I covered Tunisia’s pre-colonial history, while Part II tackled French rule and independence. Now, let's unpack how Bourguiba built modern Tunisia and set the stage for everything that followed.

Habib Bourguiba (1956-1987)

Social Policy

Secular Reformer in a Muslim Nation

Habib Bourguiba, Tunisia’s first president, envisioned a modern, secular Tunisia, often mirroring Turkey’s Atatürk. He openly challenged Islamic traditions, famously drinking orange juice on TV during Ramadan to discourage fasting, arguing it harmed productivity. He reformed the al-Zaytuna Mosque into a modern university. His government abolished polygamy, legalized abortion, allowed women to initiate divorce, permitted women to wear miniskirts, banned the hijab (calling it an "odious rag"), suppressed conservative clerics and replaced Sharia courts with secular ones.

Opposition came from all sides—Islamists, Pan-Arabists, communists, and monarchists. Despite assassination attempts, Bourguiba solidified his rule, becoming president for life in 1975.

Social Development and Population Pressure

Bourguiba expanded healthcare, education, sanitation, and infrastructure, drastically reducing infant mortality. However, this success led to rapid population growth that outpaced economic opportunities, fueling slums and youth unemployment. To ease the strain, he implemented Africa’s first nationwide family planning initiative and signed guest-worker agreements with neighboring states, the U.S., Europe, and Gulf monarchies, placing 80,000 Tunisians abroad.

Economic Policy

State-Controlled Modernization (1962-1971)

Under the Destourian Socialist Party, Finance Minister Ahmed Ben Salah launched an ambitious ten-year economic plan focusing on collective farming, import-substitution industrialization, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and nationalization of European-owned industries. Foreign investment—except in hotels and tourism—was discouraged as 'economic colonialism.' Only a small portion of private enterprise remained in household and large-scale farming.

Bourguiba leveraged Western ties to import machinery, provide technical training to locals, and expand commercial agriculture. French and German technicians were utilized until Tunisians gained the necessary skills. Heavy borrowing financed state-run factories producing processed food, steel, refined petrol, textiles, automobiles, and more. In 1959, Tunisia joined the European Economic Community as an associate member, gaining access to export olive oil and phosphate to Europe.

However, SOE inefficiencies, debt escalation, and poorly managed collectivization led to economic collapse by the late 1960s.

Collectivized farming backfired. Agricultural productivity in wheat, fruit, and olive oil plummeted due to bureaucratic mismanagement, unrealistic targets, and bad soil preservation.

By 1969, only 15% of agricultural cooperatives were profitable, causing widespread unrest, suicide, sabotage, and protests. The Tunisian government imprisoned farmers for resisting or wanting their own independent farm. This was known as the “Great Crisis of Extreme Collectivization.” The country teetered on the edge of bankruptcy.

Ben Salah wanted to double down on collectivization by nationalizing all land, but he was ousted as finance head that year for gross mismanagement. Ben Salah left to France in exile.

Besides failed internal policies, as a result of Tunisia’s early issues with France (We will get to that later), French President Charles de Gaulle, retaliated by cutting $40M in annual aid in 1964. Tunisia tried to raise taxes to compensate for aid loss, but it wasn’t enough. Tunisia still needed external financing; in addition, the country faced a current account deficit and foreign currency shortages. As a result, Tunisia sought IMF loans, World Bank loans, and syndicated loans from American & German banks.

The IMF advised Tunisia to devalue the dinar by 25% to boost exports. But, devaluation is a two sided coin. While this made Tunisian goods more competitive, it also increased import costs for fuel, food, and fertilizers. However, during this time, Tunisia was still pursuing socialist economics and ignored other reforms. As a result, between 1965-1970, Tunisia repeatedly sought IMF & American loans.

By 1970, the New French President Pompidou resumed aid, providing Tunisia low-interest loans again.

While Tunisia had financial issues & lackluster agricultural and industrial efforts, tourism flourished. Tourism became Tunisia’s leading foreign exchange earner until oil prices soared after 1973. Resorts, historical sites, and hunting grounds attracted European tourists and provided numerous low-wage jobs for Tunisians (maids, porters, gardeners, and more).

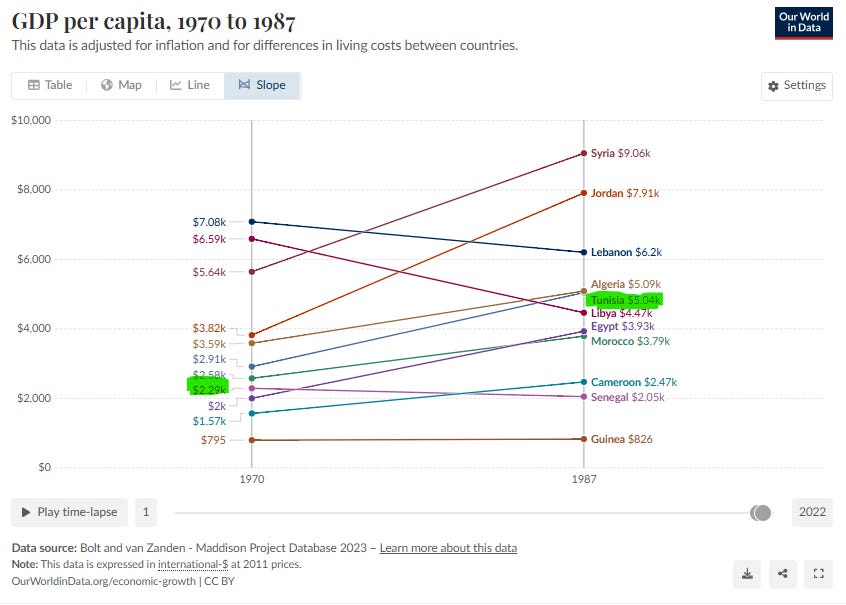

Tunisia Compared to Other Countries by 1970:

Shift Away from Socialism (1970-1980)

New Prime Minister Hedi Nouira introduced market-oriented reforms, breaking up cooperatives, allowing more private farming, and attracting foreign direct investment (FDI). The government encouraged export-driven industrialization through incentives like 10-year tax exemptions and duty-free imports of capital goods. Also, in the early 1970s, Tunisia gained favorable access to the European Common Market. This new arrangement allowed Tunisia to export industrial goods tariff-free while Tunisia could still protect its young industries. Farmers, particularly orange and olive oil producers benefited.

His policies had some successes:

500+ foreign owned factories opened in four years. FDI increased. General Motors, Renault, and others made car plants in Tunisia. Other firms came in to make food processing, textiles, and leather goods. Growth surged in tourism, textiles, and leather manufacturing.

Collective farms were redistributed to peasants as household farms. This alone helped Tunisia’s agricultural production increase 70% immediately after people farmed for themselves.

Foreign investment surged, but the government was still committed to state-led growth. 100+ new state owned enterprises were opened up in heavy industry during this time.

Lastly, another boom for Tunisia was oil. The Italian firm, Eni, found oil in al-Borma in the 1960s.

By 1974, oil briefly became Tunisia’s most valuable export commodity. Oil revenues helped maintain food and fuel subsidies (particularly for bread, couscous, and vegetable oil) and supported an inflated public sector. In 1982, Tunisia joined the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC).

While industrialization & oil money expanded, job creation lagged behind expectations. Most industrial jobs remained concentrated along the coast, leaving central and southern Tunisia underdeveloped. Unemployment remained between 13–16%, and many small farmers abandoned farms to move to urban areas due to lack of capital and being unable to compete with mechanized farms.

The business environment in Tunisia was very subpar. Tunisia maintained a licensing regime reminiscent of India’s License Raj, where securing business permits often depended on insider connections. The system was byzantine, regulating nearly every facet of business life. A single project could require more than 40 separate bureaucratic approvals just to get off the ground. Constantly shifting laws and opaque regulations further compounded the challenge, making it nearly impossible to navigate the system without contacts inside the state. For many entrepreneurs, knowing the rules wasn’t enough—they needed access to the gatekeepers who enforced them.

To add insult to injury, Tunisia’s dependence on European markets proved risky. In 1977, the European Economic Community (EEC) imposed high tariffs on Tunisian manufactured goods and restricted Tunisia’s major exports (olive oil & citrus fruits) in favor of Italian equivalents. Tariffs made Tunisian manufactured goods uncompetitive in European markets. Lower sales led to closure of factories, crippling Tunisia’s industrial growth and exacerbating economic disparities.

By the 1980s, economic challenges mounted. Nouria had a stroke and was replaced with Mohammed Mzali for Prime Minister. The 1980s were a horrible decade for Tunisia since crude oil prices fell, which was the lifeblood of Tunisia’s economy. Exports decreased from 800M dinars in 1984 to 300M by 1986.

There was also a drought in 1984 which cut harvests in half. The Tunisian dinar was weakening to dollar swiftly, causing rising inflation for imports. Also, subsidy cuts, high unemployment, a recession, and stagnating wages led to widespread discontent. Bourguiba responded with repression:

1984 Bread Riots: Austerity measures, including the removal of bread and semolina subsidies (main ingredient for couscous), caused prices to double, sparking violent protests. Protestors also complained about widespread corruption and drug smuggling. The government declared a state of emergency, deploying tanks and killing over 150 protestors. Facing backlash, Bourguiba reinstated subsidies.

Tunisia’s financial reserves were depleted, prompting the government to impose a two-year wage freeze in 1985, triggering widespread strikes.

The country had a massive balance of payments deficit, with low foreign reserves and high debt servicing costs that were 25% of government revenue.

In 1986, the country was virtually bankrupt. Tunisia pleaded for loans from the IMF and World Bank. Unfortunately, to get the loan, Tunisia had to restore investor confidence which meant currency devaluation and removing subsidies.

Foreign Policy

Sub-Saharan Africa:

Bourguiba was mostly indifferent toward Sub-Saharan Africa but joined the Organization of African Unity in 1963, primarily opposing Portugal’s continued colonialism and Apartheid South Africa.

The West:

Bourguiba leaned pro-West. Tunisia secured strong relationships and substantial aid from Western nations, notably the U.S., West Germany, France, Italy, and Sweden. The U.S. alone provided $700 million between independence to 1973, funding major projects such as the Tunis-Carthage airport to keep Tunisia from Soviet influence like Algeria, Libya, or Egypt was at the time.

Under Eisenhower, the U.S. provided free arms, pledged to protect Tunisia from its Pan-Arabist neighbors (Algeria, Gaddafi’s Libya, Nasser’s Egypt) and funded projects like the Oued Nebhana dam, while West Germany assisted with fishing modernization. In return, Tunisia granted the U.S. access to its ports and airfields in the Mediterranean. Also, JFK & LBJ, ramped up Peace Corps projects for city planning in Tunisia.

Complex Issues with France:

3000 French officials worked in Tunisia - from schools, state owned enterprises, and medical facilities. However, relations with France soured after four events:

Rejecting France as its primary military provider

Helping Algerian independence

Fighting France in the Bizerte Crisis

Expropriating land from French settlers in Tunisia

Rejecting France: A year after French independence, Bourguiba secured weapons from the U.S. and U.K., angering France.

Algeria: Bourguiba supported Algeria’s struggle for independence by hosting rebels and their government-in-exile, leading France to suspend aid, airstrike villages on the Tunisian-Algerian border, and spy on Tunisia. Despite supporting Algeria, Tunisia had issues with Algeria! This was highlighted by Bourguiba surviving an assassination attempt attributed to Algerian influence on Christmas Eve.

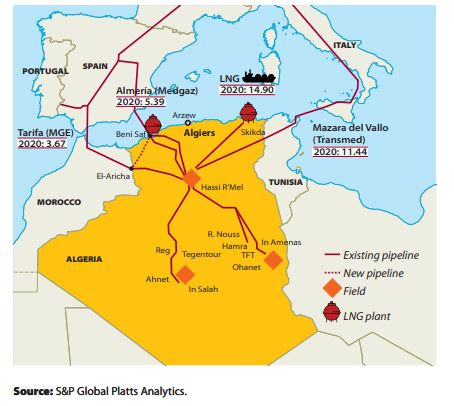

By 1970, Tunisia and Algeria signed a treaty to renew relations and collaborate on the TransMed pipeline to transport Algerian gas through Tunisia to Europe, allowing Tunisia to collect transit fees.

Bizerte Crisis (1961-1963): When France was bombing Algerians and killing Tunisians in border towns, Bourguiba responded by demanding a withdrawal of French troops from the Bizerte military base on Tunisian soil. In 1961, Bourguiba urged party officials to get Tunisian soldiers & volunteers to clash with France over the naval base, resulting in 1,000 Tunisian deaths.

Tunisia took the Bizerte Crisis to the UN, which voted on France leaving Bizerte. France finally withdrew in 1963.

Land Reform: Bourguiba nationalized most of the 700,000 acres in the Majadra Valley and surrounding areas. By 1964, most European-owned farms were nationalized without indemnity (not paying the French back).

The Algeria, Bizerte, & land reform crisis led to a European exodus where over 100K+ rural & urban European settlers left the country. The emigration wave was terrible for Tunisia, as it meant Tunisia lost large numbers of doctors, nurses, lawyers, engineers, civil servants, entrepreneurs, managers, and more. Without European farmers who used modern machines to farm, farming productivity collapsed.

Middle East:

In 1958, Tunisia, along with Morocco, joined the Arab League. However, Bourguiba rejected Pan-Arabism, breaking diplomatic ties with Nasser’s United Arab Republic (Egypt, Syria, & Gaza) and calling Nasser an aspiring "dictator" of the Arab world. Leaders like Nasser, Gaddafi, and Boumediene derided him as a Western puppet. Syrian agents tried to subvert his government by financing radical groups. Tunisia’s relations with Egypt only improved after Nasser’s death.

He had stronger relations with Gulf Monarchies, receiving aid and cheap loans from countries like Kuwait.

Tunisia-Israel relations: Bourguiba’s Balancing Act

Jewish Emigration: Following Israel’s creation in 1948, ~12K Tunisian Jews emigrated. However, Tunisia still had 100K Jews at independence in 1956, with many residing on the island of Djerba. Some Jews even served in Bourguiba’s administration.

Tensions escalated after the Suez Crisis (1956), when anti-Jewish riots erupted in Tunis, sparking a mass exodus. By 1957, around 65K Jews had left Tunisia, primarily for France and Israel. After the Six-Day War (1967), gangs attacked Tunisian Jewish businesses and the main synagogue in Tunis. By 1980, only 5K remained.

Bourguiba’s Anti-Zionist Phase: Initially, Bourguiba adopted an anti-Zionist position to align with the broader Arab world. He delivered an anti-Israel speech at the Organization of African Unity (1964), condemning Zionism. He also revoked citizenship from Tunisian Jews who visited Israel. But his mind changed next year.

The 1965 Jericho Speech: A Call for Peaceful Coexistence: In 1965, while the West Bank was still under Jordanian control, Bourguiba shocked the Arab world by advocating for negotiations with Israel. Speaking in Jericho, he urged Arab leaders to accept the 1947 UN Partition Plan, arguing that diplomacy—not Jihad—was the best way to resolve the conflict.

His remarks infuriated Egyptian President Nasser, who labeled him a traitor. At a Palestinian refugee camp, Bourguiba was nearly stoned to death by an angry crowd for his proposal.

While Tunisia sent a token force in the 1967 war, Bourguiba boycotted the Khartoum Conference, rejecting the Arab League’s hardline “no peace, no negotiation, no recognition” stance on Israel.

Continued Struggles with Arab Leaders: Bourguiba again called for a "just and lasting peace" before the 1973 war, in Geneva, acknowledging Israel’s right to exist—infuriating much of the Arab world. He also called Jordan an "artificial entity" that should be part of Palestine, briefly severing ties with Jordanian King Hussein before walking back the comment.

Despite his calls for diplomacy, when the 1973 war erupted, Tunisia sent 800 troops to support Egypt and Syria, claiming it was about reclaiming lost Arab land rather than destroying Israel. Afterward, Bourguiba pushed for a Palestinian solution based on the 1947 UN Partition Plan, which neither side accepted.

Hosting the PLO & Israeli Retaliation: In 1982, under Reagan’s encouragement, Tunisia provided refuge to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) after it was expelled from Lebanon during its civil war. Yasser Arafat and 1,100 PLO fighters moved to Tunis, which was also the new Arab League headquarters after Egypt made “peace” with Israel. The PLO received a “hero’s welcome” and lived comfortably in Tunisian villas.

On October 1, 1985, Israel bombed the PLO headquarters in Tunis, killing 60 Palestinians and 12 Tunisians, in retaliation for a PLO attack in Cyprus that killed three Israeli civilians six days earlier. Tunisia condemned Israel and said “the bombing was a terrorist act”, while the Reagan administration defended Israel’s airstrike as “a legitimate response”. Bourguiba's administration was shocked because Reagan told them to host the PLO in the first place.

This bombing temporarily crippled Tunisia’s tourism industry - the second pillar that sustained Tunisia’s economy once oil prices collapsed.

The UN drafted a resolution to sanction Israel, but America vetoed it.

Tunisia-Libya Relations:

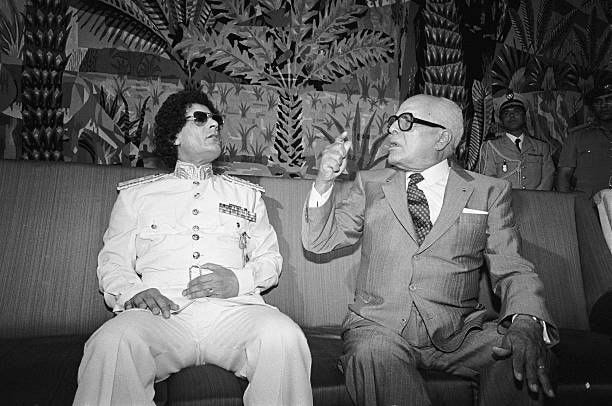

In the early 1970s, Gaddafi sought to merge Libya and Tunisia into an “Arab Islamic Republic.” Bourguiba was initially receptive — 40K Tunisians were already guest workers in Libya and Gaddafi gave aid to Tunisia after a terrible flood. Also, Tunisians were already illegally migrating to Libya for jobs. However, in 1974, Bourguiba backed out, pleasing the leaders of Algeria and Morocco who hated Gaddafi.

The differences were stark—Tunisia was relatively liberal, Libya was conservative. A guy can take out a girl out in Tunis in the evening. But in Tripoli, if a girl went out with a guy at the time, the girl would be disgraced for life. Tunisia had a vibrant night life, Libya’s was relatively austere. Also, foreign policy wise, Tunisia tolerated Israel, Gaddafi wanted Israel destroyed.

Furious with Bourguiba reneging, Gaddafi expelled 1,000 Tunisian guest workers, chopped off the hands of Tunisian detainees in Libyan jails, accused Tunisian women of prostitution, and even attempted to assassinate Bourguiba in 1975. After failing, Gaddafi then funded opposition groups, including radical elements within Tunisia’s largest labor union.

Labor Unrest and Violence

With inflation soaring, in 1973, Bourguiba attempted to regulate wages through a tripartite system involving the government, unions, and employers, but simultaneously outlawed strikes. Discontent erupted in 1978 when the General Union of Tunisian Workers (UGTT) launched a nationwide strike over wages and inflation. Riots escalated into arson and looting across multiple cities. The government declared a state of emergency, and security forces killed 190 protesters in what became known as Black Thursday.

Gaddafi’s Continued Destabilization

“Libya is aggressive, and national unity must be shown” —Ahmed Mestiri, Tunisia’s Minister of Interior.

By the 1980s, Gaddafi escalated his attacks on Tunisia:

Backed an armed uprising in Gafsa, killing 41 people in 1980.

Expelled 30K Tunisian workers, further destabilizing Tunisia’s struggling economy in 1985.

Violated Tunisia’s airspace with fighter jets and amassed troops on the border.

Told Libyan agents to loot the home of a Tunisian diplomat in Tripoli.

As a result, Reagan pledged protect Bourguiba’s Tunisia from Gaddafi.

Internal Opposition to Bourguiba

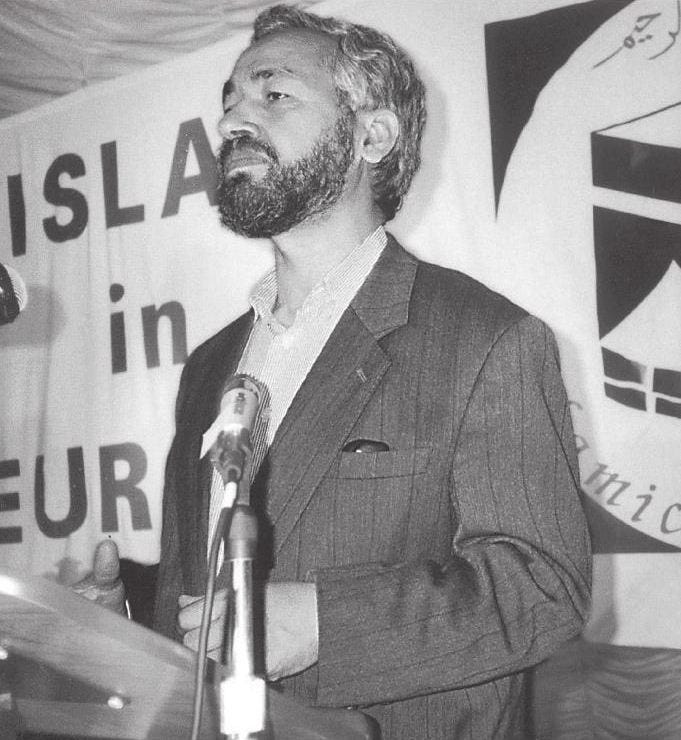

Decades of secular repression fueled Islamist resistance, culminating in the formation of Ennahda (Movement of Islamic Tendency) in 1981, led by Rached Ghannouchi. Influenced by Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood and Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution, Ennahda condemned Westernization, attributing Tunisia’s moral, economic, and social decline to Bourguiba’s secularism.

A big cohort of Tunisians remained religiously conservative and resented Bourguiba’s authoritarian secularism. Inspired by Iran’s revolution, conservative students at the University of Tunis spearheaded the movement, advocating for an Islamic state under Sharia. Ennahda’s support base grew rapidly among unemployed graduates, religious conservatives, women who wanted to wear the veil, and middle-class Tunisians disillusioned with both socialism and capitalism.

Fearing Ennahda’s rising popularity, Bourguiba banned the party in 1982 and jailed dozens of ultra-conservative clerics. Despite this, the movement persisted. By 1984, as Tunisia’s economy crumbled, Ennahda’s anti-government demonstrations escalated. At the U.S. Embassy, protesters chanted "Down with America! Up with Islam!" In response:

Civil servants were banned from praying at work.

Mosques were shut down.

Terrorism and Crackdown (1987)

By the late 1980s, Islamist opposition turned militant. In August 1987, bombs exploded in tourist hotels in Sousse and Monastir, devastating Tunisia’s tourism industry. Ennahda was blamed.

In October 1987, Bourguiba appointed Ben Ali as Prime Minister, who swiftly arrested 90 Islamists accused of plotting an Islamic Republic. Some were executed, while others were imprisoned, marking the regime’s harshest crackdown on religious opposition.

By November 1987, the Prime Minister Ben Ali ousted Bourguiba and claimed that Bourguiba was too old (84) and mentally incapable of being President.

When Ben Ali took over, in 1987, Tunisia remained North Africa’s 2nd-richest country, largely because Libya was weakened by sanctions and falling oil prices, while much of the region faced economic struggles. However, by 1987, Tunisia was still significantly poorer than its non-oil Arab peers like Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan.

Conclusion

Bourguiba is your classic secular autocratic modernizer —a leader who saw his people as backward and believed “forced progress” was the only path forward. He waged war on Islamism, but as the economy crumbled and Israel bombed Tunisia in 1985, Islamism only grew stronger.

Tunisia’s economic history in a nutshell? Flirt with socialism, watch it fail, pivot to exports, oil, foreign investment, and tourism. It worked—until oil prices crashed in the 1980s, sending Tunisia spiraling toward bankruptcy for IMF bailouts.

With Bourguiba ousted, the stage was set for Ben Ali, the Arab Spring, & more in Part 4.

Seems like the story of so many developing countries. Flirt with socialism, or at least state-led development, suffer conomic stagnation, then pivot to export focused growth only to be thrown all over the place by the chaotic dynamic of the world market. No matter what policy you pursue it seems that a disaster lurks in every corner

This is a great summary - thank you.