The Economic & Geopolitical History of Tunisia Part 4: The New Strongman Ben Ali, the Arab Spring, and the Troika

North Africa's Failed Deng Xiaoping: Revolution, Collapse, and the Struggle to Rebuild

Part 1 traced Tunisia’s pre-colonial history—from Carthaginian to Roman, Byzantine, Arab, and Ottoman Turk rule—while noting periods of indigenous Berber governance.

Part 2 explored Tunisia's era under the Husainid dynasty, when it was nominally ruled by Ottoman Turks but operated with significant autonomy. The Husainids' reckless borrowing from bankers in Paris soon plunged Tunisia into foreign financial control of the economy, paving the way for French colonization in 1881. We concluded by examining Tunisia’s eventual path to independence in 1956.

Part 3 focused on Habib Bourguiba, who aimed to build a secular, modern state modeled on France & Turkey. Though he expanded education and women’s rights, his autocratic style stifled dissent. His state-led economy struggled by the 70s. Growth rebounded with limited market liberalization, but by the 1980s, Tunisia’s dependence on tourism, crude oil, and exports to Europe proved vulnerable during European downturns and low oil prices.

Bourguiba’s militant secularism, including publicly breaking the Ramadan fast, alienated many religious conservatives. He famously declared, “If the Prophet were alive, he would not give you what I have given you.”

By the late 1980s, with Bourguiba in mental decline, Prime Minister Zine El Abidine Ben Ali seized power in a bloodless coup, renaming the ruling party the Democratic Constitutional Rally (RCD).

Zine El Abidine Ben Ali (1987-2011)

We will analyze Ali’s administration before 2000 across social, regional, geopolitical, and economic dimensions, then examine his rule post-2000.

Social

Initially promising democratic openness, Ben Ali freed 5,000 Islamists from prison, abolished a political tribunal, legalized opposition parties, and relaxed press restrictions. Movement of Islamic Tendencies, or its rename, Hizb al-Nahda (Ennahda, which means Renaissance), Tunisia’s main Islamist party, became the largest opposition group. However, Ben Ali reversed course by cracking down on Ennahda in 1991 after 300 Islamists tried to overthrow his government. Also, the Algerian Civil War in 1992 served as a warning for Ali.

He saw how the Algerian Islamists’ election victory led to a civil war after the secular autocrats annulled the results. Determined to avoid a similar fate, Ben Ali suppressed Islamists, securing easy election wins for himself.

Facing political repression, Ennahda’s leader, Rachid Ghannouchi, fled to exile in Europe. Leadership then passed to Abd al-Fattah Mourou, who shifted from militancy to moderate Islam.

Also, unlike the founder Bourguiba, Ben Ali publicly displayed Islamic piety: broadcasting the Muslim call to prayer on TV & Radio, showcasing his pilgrimage to Mecca, and incorporating religious language in speeches such as invoking “Allah the Compassionate & Merciful”— to appease conservatives. Yet, he tightly controlled religious political activity and upheld secular laws, including protections for women.

Regional Relations

Ben Ali quickly restored diplomatic ties with Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi in 1987, improving trade, tourism, and employment opportunities for Tunisians. This also meant Ali no longer had run up Tunisia’s national credit card to buy American fighter jets and tanks from Reagan intended to deter Gaddafi’s expansionism.

In 1989, Tunisia joined Algeria, Morocco, Mauritania, and Libya to form a regional bloc, the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU).

However, internal disputes—particularly Morocco's conflict over Western Sahara—made the union ineffective. Libya & Algeria backed the Polisario Front and claimed Morocco is an occupier of Western Sahara, while Morocco claimed sovereignty over the territory. The disagreement collapsed the union into a legal fiction by 1995.

Geopolitical

Israel-Palestine

Tunisia remained a diplomatic hub for the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). Despite Israeli Mossad agents’ assassination of senior PLO official Abu Jihad in Tunis in 1988, Tunisia facilitated key dialogues between the PLO and the USA, culminating in the PLO recognizing Israel’s right to exist (with caveats). After the Oslo Accords, PLO leadership moved from Tunis to the West Bank.

The Gulf War

During the 1991 Gulf War, when Iraq tried to annex Kuwait, Ben Ali refused to join the U.S.-led coalition against Iraq or impose sanctions on Saddam Hussein. Instead, Ali openly criticized the war's devastating impact on Iraq. Ben Ali's position reflected popular Tunisian sentiment, which sympathized with Saddam Hussein as a figure opposing Western hegemony—particularly amid outrage over Israeli actions against Palestinians during the 1st Intifada. Additionally, many Tunisians viewed Kuwait negatively, perceiving it as a Western-backed puppet monarchy. Ali’s actions angered France, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the US, leading to a steep drop in foreign aid and tourism revenue for Tunisia. Economic recovery took until 1992, and diplomatic relations with Kuwait resumed only in 1994.

Economical

Ben Ali’s early Years: IMF Orthodoxy

When Ben Ali took office, Tunisia was on the brink of bankruptcy. The country had already entered an IMF stabilization program. The Late 80s were a difficult time for Tunisia, unemployment was high and locust swarms decimated agricultural production. George H.W. Bush threw $130M in aid to help Tunisia cope.

In 1988, Ali entered a new IMF stabilization program, receiving $207 million in extended IMF loans, contingent on sweeping reforms. Ben Ali implemented sweeping austerity & neoliberal measures: privatizing/partially privatizing over 160 state enterprises (raising $600M in government revenue), installing a Value-Added Tax (VAT) to raise revenue to reduce reliance on foreign borrowing, slashing tariffs and easing import restrictions, devaluing the dinar to promote exports and curb the black market, hiking interest rates to curb inflation, reducing food & fuel subsidies and freezing public sector wages to control government spending.

Although macroeconomic indicators rebounded and inflation stabilized, social costs were severe. Subsidy cuts raised prices for basics like milk, sugar, and fuel. Farmers and small businesses suffered, triggering rural unemployment and unrest. Low-interest loans from the World Bank ($250 million) and Japan ($120 million) softened—but did not prevent—the social backlash.

Market Liberalization Push

In 1993, Ben Ali launched Special Economic Zones (SEZs), inspired by China's successful model, in Bizerte and Zarzis Park.

These zones successfully attracted foreign investment, spurred export-led growth in textiles, wires, & cables, and more tourism. European firms employed over 200K Tunisians in textiles sector by 2008. However, outside these pockets, the rest of Tunisia remained burdened by heavy regulations, burdensome licenses, and monopolistic practices from the Bourguiba era, known sarcastically as the “Kingdom of Licenses”.

This created a stark "onshore-offshore" divide: dynamic SEZ areas flourished, while non-SEZ regions stagnated, dominated by corruption, bureaucracy, and inefficient firms dependent on political favors.

The result was profound regional inequality—relatively prosperous coastal cities contrasted sharply with impoverished interior regions, locked in chronic poverty & red tape.

Protecting Infant Industries/ Cronyism

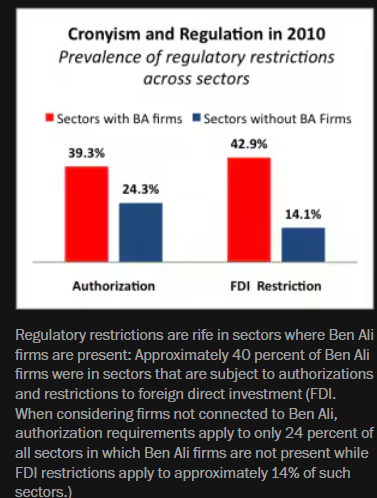

Ben Ali's government continued restricting competition in “strategic sectors” such as telecommunications, water, transport, tourism, real estate, and advertising. Tunisia initially justified protectionist policies under the "infant industry" argument—shielding new industries under the state until they matured. However, the remaining state-owned enterprises essentially served as fronts for Ali’s family businesses, particularly in air transport, energy, and trade.

Due to protection from competition, these state-owned firms became profitable but complacent. For example, international phone calls in Tunisia cost 40 times the global market rate, ranking Tunisia third globally for the most expensive international calls. Firms like Tunisia Telecom and Ooredoo Tunisia thrived at citizens' expense.

Prolonged protection without competitive pressures produced inefficient companies thriving on cronyism rather than innovation. These protected firms became what critics call “obese infants,” unable to compete globally or even locally without special privileges.

Integration with the European Market

In 1995, Tunisia joined the World Trade Organization (WTO), secured its first international credit rating, and entered a free trade deal with the European Union(EU). Under the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership, this agreement eliminated tariffs on industrial products traded between EU & Tunisia, although agricultural, agri-processing, and fish markets remained partially protected. With credit access, Tunisia could raise funds from private investors. Tunisia started issuing eurobonds and samurai-bonds(denominated in yen) in 1997.

By the mid-1990s, the EU became Tunisia’s largest trading partner, accounting for 70% of Tunisia’s imports and 80% of its exports. However, joining the WTO meant losing 20% of government revenue previously earned through tariffs on European imports. To offset this loss, Tunisia increased VAT taxes, disproportionately affecting lower-income groups.

The result of these policies transformed Tunisia from a phosphate, crude & olive oil exporter into a wire, textile, and cable hub for Europe.

Social Costs and Public Backlash

Removing tariff protections exposed many small and medium-sized Tunisian businesses, especially traditional industries, to fierce international competition. Though consumers benefited from higher quality goods from Europe, many local firms collapsed. Interior regions like Kasserine, Gafsa, and Sidi Bouzid lagged behind the coast in infrastructure, education and jobs. The Ali government tried to remedy the inequalities by spending half of the government budget on education, health, and social services.

Ben Ali's economic policies, combined with his police-state style, political repression tactics—particularly against the Islamist Ennahda party—deepened public resentment. Elections became meaningless, reinforcing public frustration over the lack of genuine democratic pluralism, lack of religious political activism, and equitable economic growth. Ennahda secretly provided welfare for the poor regions, including clean drinking water, housing, healthcare and schooling in these regions.

The 2000s

By the 2000s, Tunisia had improved literacy and life expectancy, and tourism employed (directly & indirectly) over 12% of the population. Manufacturing exports in wires, cables, and textiles increased, and Tunisia was doing deals with China. However, growth was fragile and Tunisia was unable to move beyond assembly and low-value added tasks for Italian and French firms. 75% of Tunisians worked in low productivity sectors.

Many Tunisians were still unemployed and embarked on dangerous boat rides to Lampedusa or Sicily, Italy for menial jobs with Sub-Saharan Africans.

After 9/11 and a terrorist bombing in a Synagogue in Djerba, Tunisia in 2002, tourism temporarily plunged. It took until the mid 2000s for Tunisian tourism to recover.

In 2004, Tunisia tried regional integration again by signing the Agadir Agreement with Jordan, Egypt, and Morocco, but Middle Eastern trade was negligible compared to European trade.

Militant Jihadism had some ears in Tunisia. There were Jihadist Groups linked to Al-Qaeda in Tunisia and a Tunisian Militant carried a terrorist attack in Madrid in 2004. As a result, Ben Ali worked closely with the Bush Administration’s “War on Terror” to curb militant ideology in his country.

Pre-cursor to the Arab Spring

Corruption

With each passing term, Ben Ali grew increasingly disconnected from the harsh economic realities facing Tunisia’s youth. His government thrived on corruption, stifling civil society through repression, censorship, and torture.

While ordinary Tunisians struggled, Ben Ali’s family lived lavishly. His second wife, Leila Trabelsi, became notorious as the lavish “Queen of Carthage” for enriching her ten siblings at the country’s expense, systematically destroying businesses through nepotism and intimidation. Competition laws were changed for the Ali family’s benefit. The Ali family’s business empire ballooned to over 440 companies, spanning airlines, hotels, media outlets, car dealerships, and real estate. They had 550 properties, 48 boats & yachts, 40 stock portfolios, and 367 bank accounts amounting to over $13B. At its peak, they pocketed nearly a fifth of Tunisia’s total annual profits. Authorities later discovered $27 million in hidden cash and jewelry stashed in the family's palaces.

Privatization, intended to boost economic efficiency, became a lucrative tool for regime insiders. Ben Ali’s circle secured sweetheart deals for state-owned firms, extracting hefty bribes and kickbacks from international investors seeking business in Tunisia. Profits were funneled into offshore accounts in Europe (i.e. Switzerland)—a classic tale of corruption in the developing world.

Ben Ali’s relatives flocked to sectors riddled with regulations. Entry restrictions to these sectors translated to higher market share, higher prices, and more money for the firms owned by Ben Ali’s extended family, who had privileged access. McDonald’s couldn’t enter Tunisia when McDonald awarded franchises to the “wrong” business partner!

When existing regulations didn’t sufficiently shield family businesses from competition, the Ben Ali made new regulations introducing new authorization requirements. The people that were able to navigate through the new regulations were Ben Ali’s clan. Ben Ali had an opportunity to reform the onerous license regime created by his predecessor. But instead, he exacerbated it so his family could benefit.

The early signals for revolution existed. In October 2005, many Tunisians from unions, leftists, and Islamists went on a massive hunger strike. But we are just getting started when it comes to early signals.

Gafsa protests

The 2008 global financial crisis deeply impacted Tunisia, sharply reducing demand for phosphate—one of the country’s key exports. Facing declining revenues and general hardships, the state-owned Gafsa Phosphate Company (CPG) laid off nearly 10,000 workers, sparking massive unrest.

For six turbulent months, mining towns like Redeyef, Moulares, Metlaoui, and Mdhilla erupted in strikes, sit-ins, hunger strikes, and demonstrations. Protesters blocked railway lines used to transport phosphate, demanding jobs, ending environmental degradation, and stopping corruption.

The unrest spread across Tunisia to cities such as Kasserine, Tataouine, Hammamet, Sfax, and even Tunis, quickly becoming a nationwide anti-government movement. Security forces responded brutally, deploying live ammunition, tear gas, water cannons, and birdshot, fueling deeper resentment among citizens.

In response, President Ben Ali made only symbolic gestures—firing local officials and pardoning a handful of imprisoned protesters. Yet these concessions failed to quell anger.

The Arab Spring or the “Revolution for Dignity”

The Arab Spring was sparked by multiple intertwined factors: an economic crisis, climate change, political corruption, youth unemployment, and Twitter’s role in mobilizing public anger.

Climate

Tunisia & the rest of North Africa are big importers of wheat. Tunisia gets over 40% of its wheat from Russia, Ukraine, & Kazakhstan. In the summer of 2010, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, & Russia suffered a 1 in a 100 year drought. Putin himself ordered an export ban on grain. By winter, a shortage emerged and food prices skyrocketed.

If you look at the graph below, within a year, global wheat prices rose from $472 per bushel to $794 per bushel (a 68% increase in a year!):

The Global Financial Crisis

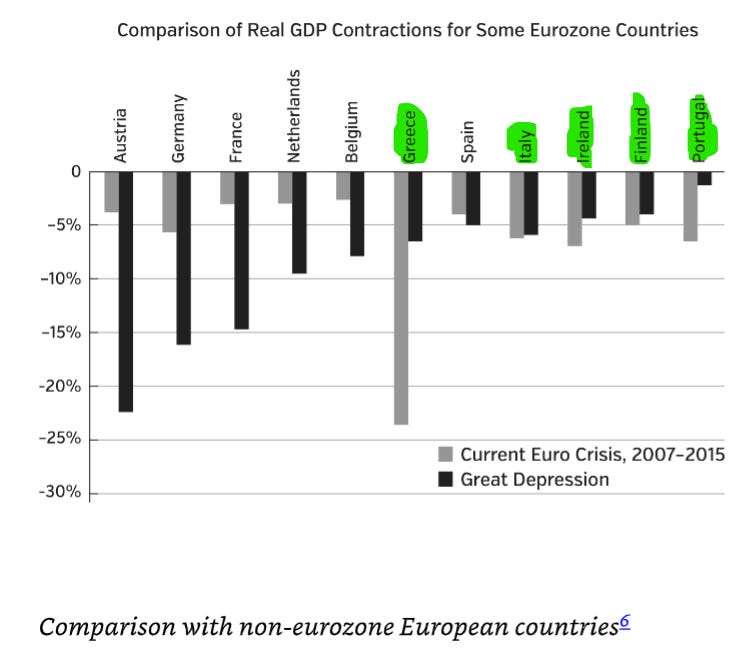

In 2008, Tunisia suffered from the Global Financial Crisis(GFC). Before the crisis, Tunisia’s trade as a percentage of economic output exceeded 100%; driven by exports to Europe. The GFC triggered Europe’s deeper Eurozone crisis, as several eurozone member states, Greece, Portugal, Ireland, and Cyprus were on the verge of default or did default, requiring IMF & EU bailouts.

The Eurozone debt crisis was worse than the 1930s Global Great Depression for many countries. In the chart below, the countries in green suffered a worse depression in the Euro Crisis than in the Great Depression that occurred nearly a century ago:

Weak European demand impacted Tunisia, as their biggest customer wasn’t buying Tunisian products. This lead to stagnation & decline in Tunisia.

Tunisians weren’t getting as many orders to make shirts, shoes, wires, or fertilizer for Europe, losing billions of dollars in one year. This led to massive unemployment, compounding the recession and food crisis. Reduced exports, combined with continued reliance on imports weakened the Tunisian dinar, fueling inflation as import costs rose.

Tunisia didn’t recover in terms of global exports until 2022!

The Unemployment Youth Bomb

Tunisia’s youth, though educated, lacked market-relevant skills, and the economy provided limited opportunities beyond low-paying informal jobs. This was true even for college graduates. Unemployment was 15% nation wide but 40% for the youth. Youth unemployment rates were especially dire in the impoverished southern and central regions(above 50%!), fueling desperation and emigration attempts.

The Trigger

The revolution ignited on December 17, 2010, when Mohamed Bouazizi, a young street vendor, faced police maltreatment. Bouazizi was being harassed by the police to pay bribes, and they stole his equipment. When Bouazizi demanded a trial, they refused. As a result, he set himself on fire in protest in Sidi Bouzid. Bouazizi’s desperate act symbolized the widespread despair and anger of Tunisians, spreading rapidly via social media.

Massive demonstrations erupted nationwide, particularly in marginalized towns like Kasserine and Thala.

Despite violent crackdowns, protesters remained defiant. Ben Ali’s attempts to appease demonstrators by promising reforms were dismissed as insufficient. The Tunisian army’s refusal to shoot protesters, under General Rachid ben Ammar’s orders, significantly weakened Ben Ali’s authority. People yelled “Ben Ali, Get Lost!’ in French and Arabic. Under relentless public pressure, Ben Ali fled to Saudi Arabia on January 14, 2011.

Tunisia’s uprising sparked similar movements across the Arab World—in Egypt (Mubarak), Libya (Gaddafi), Yemen (Saleh), Syria (Assad), and Jordan. While Egypt experienced a military coup, Libya, Yemen, and Syria descended into prolonged civil wars.

Following Ali’s ousting, Switzerland eventually froze Ben Ali’s $320M that his family stashed there.

Fouad Mebazaa (Foo-ahd Meh-bah-zah) (2011)

After Ben Ali fled, Fouad Mebazaa, Speaker of Parliament, became Tunisia’s interim President. However, young Tunisians feared a return to authoritarianism and continued protesting. The transitional period saw continued violence and unrest, with security forces often harshly suppressing demonstrations until elections took place in October 2011.

Historic Elections:

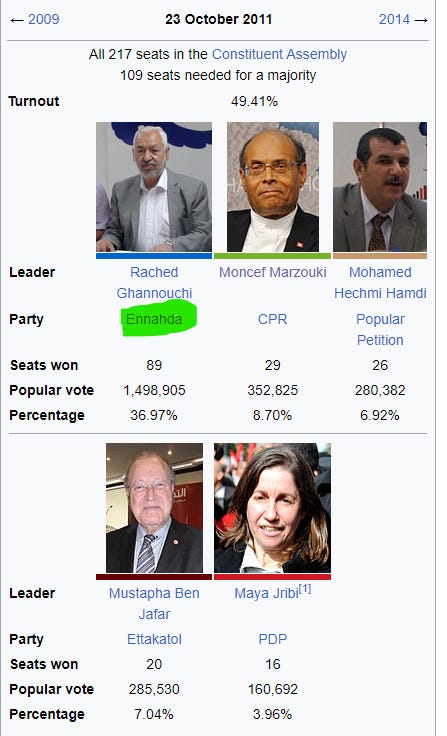

In October 2011, Tunisia held its first democratic elections with a 50% voter turnout. The moderate Islamist party Ennahda, secured 37% of the vote, while the secular Congress for the Republic (CPR) took around 9%.

Some Tunisians worried Ennahda’s victory would lead Tunisia down a path similar to Iran’s Islamic Revolution. However, Ennahda’s leader Rachid Ghannouchi explicitly rejected past violence and assured Tunisians that his party would govern democratically. By his standards, that’s more akin to Turkey’s AKP under Erdogan rather than Afghanistan’s Taliban.

Ennahda, Coalition, and New Leadership (2011–2014)

Although Ennahda won the most seats, its leader, Rachid Ghannouchi, chose not to become president. Instead, Ennahda formed a coalition known as the "Troika" with the secular Congress for the Republic (CPR) and Ettakatol party:

Moncef Marzouki, a prominent human rights activist previously exiled by Ben Ali, became interim president.

Hammadi Jebali (Ennahda) served as prime minister.

Mustafa Ben Jafar (Ettakatol) led the Constituent Assembly.

All three had been imprisoned or exiled by the former regime. At this moment due to successful elections, Tunisia was considered a “post-Arab Spring success story”. But we will discuss more about the Troika next time.

Conclusion & Insights

Ben Ali began his presidency with promises of democratic openness and economic modernization but quickly abandoned political openness amid Islamist threats and instability from neighboring Algeria's civil war. His market-oriented reforms drove economic growth along Tunisia’s coastal regions but exacerbated poverty inland, simultaneously creating fertile ground for corruption that enriched his own family and cronies.

In many ways, Ben Ali was a failed version of China's Deng Xiaoping. Both leaders restricted democratic freedoms while experimenting with market liberalization and special economic zones. However, unlike Deng, who deepened market reforms & supported rural farmers to boost broad prosperity, Ben Ali ignored farmers and prioritized personal enrichment and patronage, undermining Tunisia’s potential for sustained economic success.

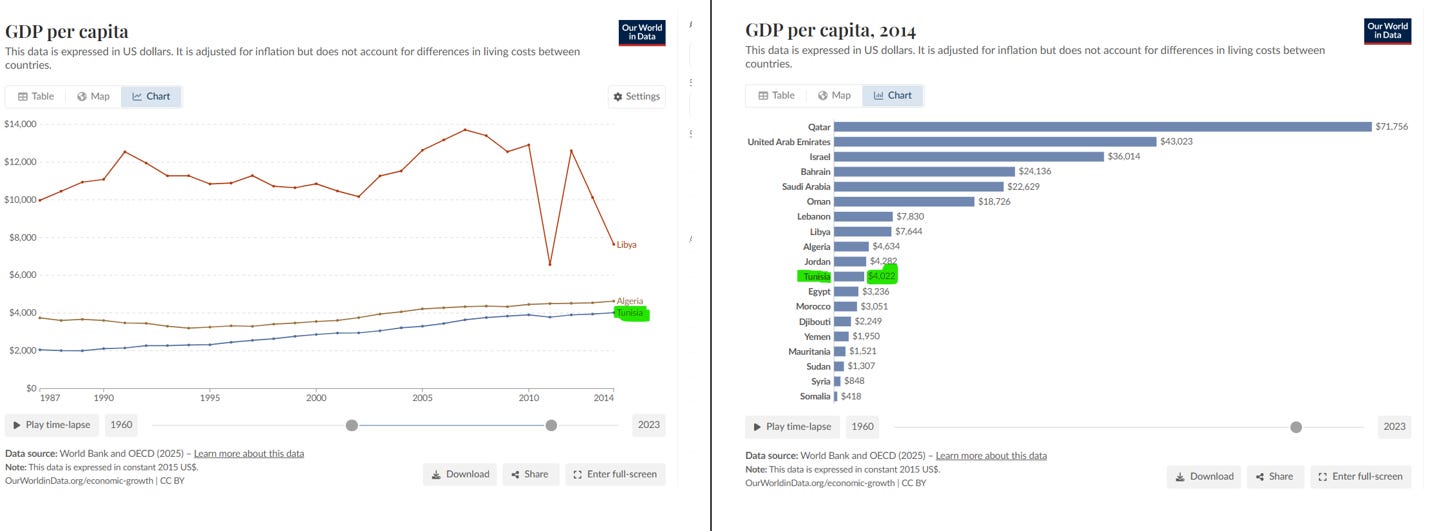

From 1987-2014, the average Tunisian went from making over $2K a year to $4K a year(market exchange rates). This is nothing compared to the Gulf living standards, but Tunisia was still keeping up with Libya & Algeria.

Ultimately, external shocks from the global financial crisis, the bread price crisis, and Eurozone crisis intensified Tunisia’s globalization vulnerabilities, sparking the Arab Spring. Luckily, after the Arab Spring, the Islamists shared power with the secularists, which made Tunisia seem like an Arab Spring success… temporarily…. Read here for the conclusion!

"Privatization, intended to boost economic efficiency, became a lucrative tool for regime insiders. Ben Ali’s circle secured sweetheart deals for state-owned firms, extracting hefty bribes and kickbacks from international investors seeking business in Tunisia. Profits were funneled into offshore accounts in Europe (i.e. Switzerland)—a classic tale of corruption in the developing world."

Sounds like Russia after the Soviet Union collapsed, yet Putin is still in power while Ben Ali is gone. My guess is this is because Russia has vast natural resources for Putin to fund his regime whereas Tunisia doesn't.