The Economic & Geopolitical History of Tunisia Part 5 - The Arab Spring’s Only “Success” Comes Full Circle

How Tunisia’s Arab Spring briefly bloomed, withered under economic strain, and gave way to a new strongman

This is the finale of my series on Tunisia. I didn’t expect Tunisia to be my first five-part series, but its history was super interesting. Here’s the Series Recap:

Part 1: Covered Tunisia’s pre-colonial past, highlighting Carthaginian, Roman, Byzantine, Arab, and Ottoman Turk periods, including Berber governance.

Part 2: Examined Tunisia’s autonomous Husainid dynasty, whose reckless borrowing from French banks led to economic crisis and French colonization (1881–1956).

Part 3: Analyzed Habib Bourguiba, the founding father of modern day Tunisia.

Part 4: Looked at Ben Ali’s regime (1987–2011), and the causes of the Arab Spring.

In this final part, we’ll look at how Tunisia has fared since the Arab Spring.

Tunisia’s Arab Spring & Transition (2011–2014)

When Ben Ali fled to Saudi Arabia in January 2011, the transitional government tried to seize $13 billion in assets (businesses, properties, and yachts) linked to Ben Ali’s family and cronies. But chaos still loomed large.

The transitional government tried to bring stability until elections were held in October 2011.

Ennahda, the Islamist party led by Rachid Ghannouchi, won 37% of the vote and formed a coalition government—known as the Troika—with two secular, center-left parties: the Congress for the Republic and Ettakatol.

So how did a party that wanted to embed Sharia in the constitution end up governing with secularists who vehemently opposed it?

Before the election, Ghannouchi toured the U.S. and UN, promising inclusive government. Cynics saw this as a strategic move to preempt Western “coup permission” —particularly the kind of tacit approval that the U.S. & Europe have previously given to coups or military interventions against elected Islamist governments. They point to precedents like Algeria in 1992, where the army cancelled elections to block the Islamic Salvation Front, sparking a civil war. Or, they point to the 2006 Palestinian elections, where Western powers isolated the Hamas-led government after its victory. Ghannouchi’s outreach aimed to avoid Ennahda suffering a similar fate.

Despite receiving significant international support —$500M from the World Bank, $400M from the EU, $500M from Qatar, and $300M from the U.S. — Ennahda struggled economically. Tourism revenues plunged from $3B (2008) to under $2.4B (2011–14). Inflation surged, over a third of the youth were unemployed, and 3,000 Tunisians joined DAESH/Islamic State in Syria.

Efforts to institutionalize Sharia law failed, and Ennahda’s relaxation of mosque oversight enabled radical Salafist preaching, leading to assassinations on secular leftist politicians (Chokri Belaid & Mohamed Brahmi) and the U.S. Embassy attack in 2012–13.

Debt & Governance Struggles (2013–2014)

As the country reeled, Tunisia’s Troika government debated a bold idea: audit the $14B in external debt racked up under Ben Ali. The goal was to classify some of it as “odious debt” potentially canceling it or converting it into development aid. Over 100 members of the European Parliament supported the Tunisian initiative as well.

But the Troika hesitated to fully embrace this approach. Why? Here are the pros and cons that the Troika likely considered:

Debt Relief:

Pros: Immediate fiscal relief. It frees up money for health, education, infrastructure, and disowns the debts of a corrupt regime.

Cons: Debt relief may offer temporary breathing room, but it rarely addresses the deeper structural issues that caused Tunisia to over-borrow in the first place—such as low tax revenues, underdeveloped domestic financial markets, and weak institutions. Moreover, debt relief often signals distress to international investors, raising future borrowing costs when the country reenters capital markets. Nearly every African country received debt relief or restructuring in the 1980s and 1990s, yet many are still saddled with the legacy of those “junk bond” ratings. As a result, these developing countries borrow at higher rates than those that never needed debt relief (Germany or U.S).

IMF Loan:

Pros: IMF loans offer lower interest rates compared to market based borrowing, providing urgently needed cash to stabilize the economy. Accepting IMF conditions signals to investors a serious commitment to economic reforms and fiscal discipline, potentially enhancing investor confidence and reducing borrowing costs over the longer term.

Cons: IMF conditionalities usually involve politically sensitive austerity measures (cuts in subsidies, reduced public spending, and tax increases), often triggering social unrest or riots. Implementing these reforms carries substantial political risk, as citizens bear the immediate brunt of austerity.

Ultimately, instead of aggressively pursuing debt relief, the Ennahda led Troika government chose to negotiate and accept a $1.7 billion IMF Stand-By Arrangement in 2013. The loan conditionalities included:

Increasing interest rates to curb inflation (“tighter monetary policy”)

Letting dinar float and devalue to boost competitiveness(“greater exchange flexibility”)

Reducing expensive subsidies for food and fuel & increasing VAT tax(“prudent fiscal policy”).

Politically painful? Yes. But Tunisia chose the stability the IMF offered—at a cost.

A Fragile Compromise: The 2014 Constitution

Fearing a repeat of Egypt’s 2013 coup, Ennahda entered a National Dialogue with secularists and civil society groups. In January 2014, the Islamist Ennahda peacefully ceded power to a technocratic government led by Mehdi Jomaa.

Tunisia adopted a new semi-presidential constitution to prevent executive overreaches abused by the pre-Arab Spring ruler, Ben Ali.

Later in 2014, Tunisia had its first election and the center-left secularist party under Beji Caid Essebsi winning first, and Ennahda coming in second. Then the nation made a new constitution. Tunisia was then considered the “Arab Spring success story”.

Beji Caid Essebsi(Eh-Seb-See) (2014-2019)

Beji Caid Essebsi—an elite from Tunisia’s old guard and a descendant of Italian Slaves in Tunisia—became Tunisia’s first freely elected president in 2014. His secular party Nidaa Tounes and Ennahda formed a power-sharing coalition. The World Bank provided a $1.2B loan in 2014 to help with his development initiatives.

But the honeymoon ended fast.

Terrorism

In 2015, there were three terrorist attacks in Tunisia perpetrated by the Islamic State:

The wave of terrorist attacks in 2015 devastated Tunisia’s tourism industry— a huge source of employment and the source of 14% of its GDP. As foreign visitors fled and resorts emptied, a crucial stream of foreign currency quickly evaporated.

High Unemployment

With the economy reeling, desperation spread. Tens of thousands of poor Tunisians began turning to smugglers, paying human traffickers to ferry them across the Mediterranean to Italy in search of work and dignity. Inside the country, unemployment remained stubbornly high—especially among youth and graduates.

In response, the government transformed into an “employer of last resort.” Since 2010, over 600K Tunisians joined the public sector, with another 180K employed by state-owned enterprises. To appease Tunisia’s powerful labor unions, the government also raised public sector wages, nearly doubling the wage bill between 2010 and 2014. By then, government salaries consumed over 13% of GDP—among the highest in the world at that time.

Yet the expansion brought little in the way of efficiency. A World Bank report bluntly noted that “the link between a public employee’s performance and her evaluation, compensation and promotion is weak—particularly since the revolution.”

American Support

Meanwhile, the security situation remained volatile. In 2015, Essebsi declared a state of emergency as the Tunisian army confronted jihadist groups—some with ties to Al-Qaeda—in remote mountain regions. To prevent Tunisia from becoming a chaotic hotbed like Libya (which Obama takes blame for the mayhem), Obama provided $1.5B in total loan guarantees and designated Tunisia as a major non-NATO ally. This is a status also shared with states like Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, New Zealand, Australia, Israel, Egypt, and Morocco.

This move granted Tunisia access to advanced U.S. military support, joint training, and defense financing—an important gesture of support during a critical moment.

Bank Bailout

Essebsi also bailed out two major state-owned banks (Société Tunisienne de Banque and Banque de l’Habita) riddled with bad loans from the Ben Ali era. A $440M recapitalization passed in 2015, funded by the government budget and international aid flows. No full audit was ever published.

IMF Reforms

In 2016, due to the bank bailouts and terrorism, Tunisia was on a path to bankruptcy. As a result, Essebsi’s government requested a $2.9B emergency loan from the IMF. The strings attached were:

Cut expensive food & fuel subsidies

Raise taxes

Privatize unprofitable state-owned enterprises

Allow the currency to float instead of anchoring its value to other currencies

Make the central bank independent like in advanced countries

Reduce wage increases for public sector workers

Cut government spending

But protests erupted. The UGTT, Tunisia’s powerful union, resisted. The Tunisian government raised wages instead of holding the line. The IMF withheld 40% of the loan for failing to meet the conditions.

In 2017- 2018, Beji tried to restore investor confidence again by following through the IMF reforms. He increased taxes, cut government spending (which can affect public schools & hospitals), allowed the dinar weaken to help exporting firms, and removing costly subsidies for fuel, wine, bread and phone cards. Protesters flooded the streets. Nearly 1,000 were arrested.

In 2019, Beji died at age 92 and legislative elections were called. Kais Saied, a conservative constitutional law professor who spoke in formal Arabic and refused campaign donations, won the presidency. Ennahda remained the largest parliamentary party.

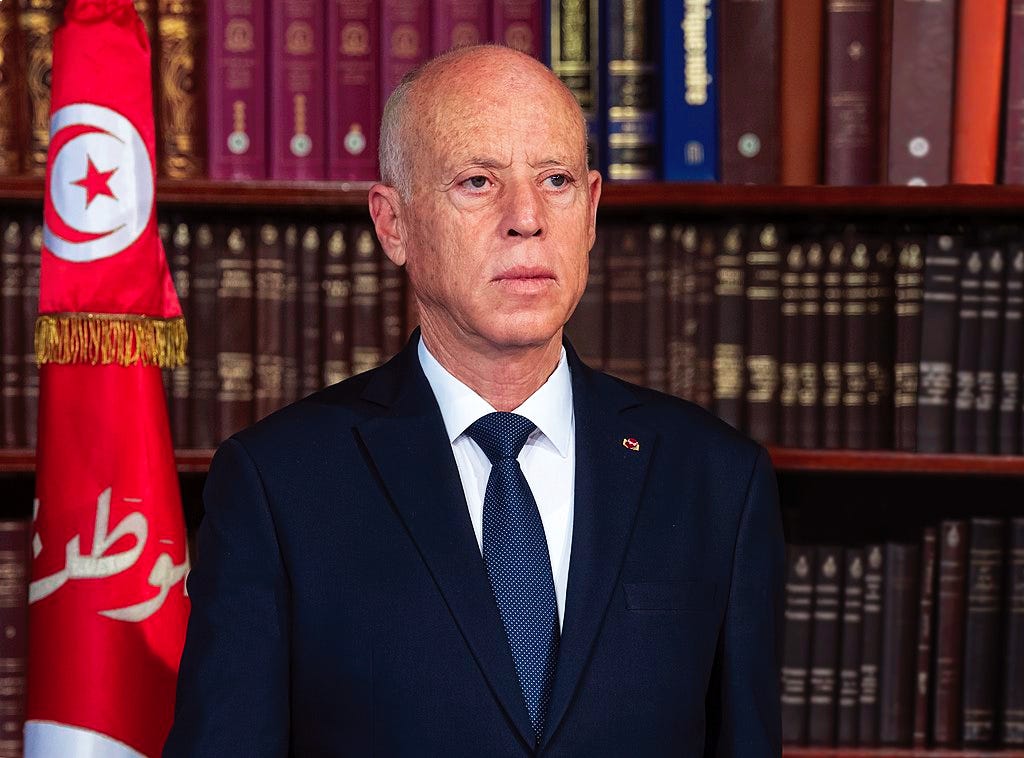

Kais Saied (2019-Present)

Kais Saied won elections in 2019, and reelections in 2024. Saied’s appeal? He marketed himself as a guy with clean hands. An incorruptible person. A human incarnation of law and order—nicknamed “RoboCop”.

COVID-19 & Autocracy

Unfortunately, COVID struck Tunisia horribly. Hospitals overflowed. Tunisia suffered more than other Middle Eastern countries.

Not one to let a “good crisis go to waste”, on July 2021, Saied invoked Article 80 of the constitution, dismissed the prime minister, and froze parliament.

.He began dismantling Tunisia’s democratic institutions:

He also arrested activists, businessmen, and the head of an independent radio station.

With no checks on his power, Saied was free to overhaul the entire state apparatus. He passed a new constitution with 94% approval— on 30% turn out.

Crisis Deepens: Debt, Drought, and Disillusionment

Due to COVID, youth unemployment hit 37% in 2022. University graduates still couldn’t find work. Food shortages plagued the country—sugar, milk, bread, even car parts were scarce. The war in Russia-Ukraine impacted wheat supplies to Tunisia.

By 2023, Tunisia teetered on the edge of default. Saied rejected a $1.9B IMF deal that year, refusing to cut food and fuel subsidies. As a result, Tunisia’s credit rating sank to ultra-junk territory, and default looked imminent.

Then oddly, olive oil exports gave Tunisia a lifeline. A severe drought in Spain, the world’s top olive oil producer, reduced supply and spiked global olive oil prices to record highs. Tunisia— one of the largest olive oil exporters —raked in precious foreign currency from olive oil exports.

Olive oil wasn’t a cure-all, but the windfall helped Tunisia delay default and repay looming debts, buying the government time amid worsening economic toil.

This gave Tunisia’s central bank the foreign currency reserves to pay interest payments. This helped reduce Tunisia’s credit risk, but this did not resolve underlying structural vulnerabilities.

With reduced credit risk, he sought funding from Saudi Arabia and the African Export-Import Bank, while refusing an IMF loan. The IMF closed its office in Tunis in early 2025 — symbolizing a diplomatic rupture after Saied refused to implement austerity measures tied to a $1.9 billion loan.

While Tunisia has temporarily avoided default, thanks to foreign exchange from olive oil exports and bilateral support, its credit rating remains in junk territory—worse than Nigeria or Egypt. Default is still a strong possibility unless new financing or major reforms emerge.

Saied’s Vision: A Developmentalist Turn?

Instead of IMF-led liberalization, Saied is betting on state-led development to create comparative advantage.

He's promoting rural “collective enterprises” on public farmland with tax breaks and low-interest loans.

He’s building energy grids with electrical connections to Italy, backed by the European Union to lower electricity costs.

He's launching desalination plants to combat water scarcity.

He is building a 10 km bridge in the northern region (built by China).

But it’s unclear whether Tunisians—especially the youth—want to be farmers like their grandparents. It’s unclear if Saied can “create comparative advantage” to make Tunisia a large steel producer.

Migration, Race, and Europe’s Border Wall

President Kais Saied has stirred controversy with anti-Black rhetoric, claiming there is a conspiracy to make Tunisia Black through “hordes of illegal migrants”. His remarks echo broader anxieties about migration and national identity—and have drawn sharp criticism from human rights groups.

At the same time, Tunisia has become a key chokepoint in the African migration route to Europe. While the majority of sub-Saharan African migrants remain within the continent, a growing number—fleeing jihadist insurgencies in the Sahel, civil wars in Sudan, and instability in eastern Congo—undertake the perilous journey across the Sahara.

When they can’t find work in Tunisia, many use Tunis as a docking station before they take a risky boat to Italy. In this sense, Tunisia now functions as a de facto outer wall of Europe’s migration policy—a heavily pressured frontline state in a broader regional crisis. In fact since 2011, the EU has provided €3.4 billion in grants and cheap loans to “outsource” border control to Tunisia. Kais Saied now uses African migrants as a Damocles over Europe’s head to get more aid.

Many—but certainly not all—Tunisians have expressed support for President Saied’s hardline stance on sub-Saharan migration. After he claimed there was a conspiracy to "Darken" Tunisia, anti-Black sentiment surged. Police evicted Black migrants from their homes, and several reports emerged of assaults and violence. Some migrants were forcibly relocated to border zones without food or shelter.

At the same time, even Tunisians themselves are fleeing the country. In early 2023, over 3,200 Tunisians crossed the Mediterranean to Italy, a 154% increase from the same period the year before.

Frankly, due to Europe’s low birth rates, high rates of education, and aging population, they have labor shortages in non-specialized labor, so they need the African migrants anyway. But as always, the problem is how different groups integrate into a formerly “homogenous society”.

Final Reflections

Among the Arab Spring countries, Tunisia stands out—not because it thrived, but because it didn’t implode. No foreign-backed proxy war like in Syria, Libya, or Yemen. No DAESH caliphate like in Iraq or, well, Syria again. No coup like in Egypt... or Syria. No uprising crushed with tanks from neighbors like in Bahrain. Tunisia had dysfunction, sure—but not total meltdown. For a brief moment, Tunisia became a rare Arab democracy and the poster child for peaceful revolution.

But more than a decade later, that hope has dimmed.

The economy is stagnant. Youth unemployment is sky-high. Tunisia’s democracy has been gutted. Real income per capita remains nearly the same as it was in 2011—about $4,000 per person or $13,000 in purchasing power terms.

Kais Saied has replaced democratic experimentation with a heavy-handed developmentalist vision—relying on state-owned infrastructure, rural collectives, and diplomatic loans from the Gulf and China. Tunisia’s credit rating is so horrible that credit investors rate Tunisia’s bonds to be worse than infamously corrupt governments like Nigeria, Angola, or Egypt.

So after all that, did the Arab Spring mean anything?

Maybe it’s too soon to tell.

Maybe Tunisia is heading for ruin, or maybe Tunisia is like France after 1789— politically allergic to stability for a century before it finally got its act together. Consider France’s own chaotic path::

1789: The French Revolution begins. Elites and radicals overthrow the monarchy, abolish feudalism, weaken the Catholic Church, and declare the Rights of Man. This marks the birth of the First Republic.

1799: Napoleon Bonaparte seizes power in a coup and crowns himself Emperor, creating the First Empire. He declares war on Europe.

1814: Napoleon falls. The monarchy is restored under Louis XVIII—the Bourbon Restoration.

1830: The July Revolution ousts Charles X (an absolute monarch) and installs Louis-Philippe, a constitutional monarch.

1848: The February Revolution ends Louis-Philippe’s reign. France briefly becomes the Second Republic. All adult men gain the right to vote. Louis-Napoleon (Napoleon III) is elected president.

1852: Louis-Napoleon stages a coup and declares himself Emperor, launching the Second Empire.

1870–1871: France loses the war against Prussia (Germany). Napoleon III is captured. A brief communist government—the Paris Commune—emerges in Paris before being violently crushed. The Third Republic is born.

It took France nearly a hundred years to move from absolute monarchy to stable republican rule. Tunisia may be on a similarly long and winding road towards something, and it might take a century for that “stable something” to emerge.

Don’t write Tunisia off just yet.

Thanks for the series, great posts. It sadly does show how geography is destiny. Many of the things happening to Tunisia - former colonization by France, tourism, migration crisis - would not have happened if the country wasn't in the place it is in. Its history is very similar to Algeria's, which I've studied. Luckily unlike both neighbors, as you emphasize, Tunisia avoided devastating civil wars.

I don't think the steel push is going to do anything, but waste a billion dollars or two. Steel never produces many jobs. It's more symptomatic of big push industrialization efforts by autocrats that failed elsewhere, most notably next door at Annaba Steel Works - the Algerians tried the same fourty years ago. Beyond tourism (El Jem, Dougga Amphiteater and Djerba are gorgeous!), the country's future might be (solar) energy, I think. That said, solar takes a long time to pay off (never good in a country in a violent neighbourhood) even if it's just 5-6 years at this point with the sun and cheap land they have. And energy projects don't produce many jobs either, just more money for extractive elites. Educating the populace seems to be tough too from the country's standpoint, since the best and brightest people will likely move north after their studies. Maybe creating a free city full of light manufacturing sweatshops would be the way out, especially with all the sub-saharan labor they have? OTOH native Tunisians are probably too rich and pampered by government wages already to want to work for little money in tiresome factory settings.