The Economic & Geopolitical History of Burkina Faso, Part 1: Pre-Sankara & His Emergence

The country's name means "The Land of Honest People"

Burkina Faso is a landlocked, low-income country in the Sahel region of West Africa. The population is predominantly Mossi tribe, but it also includes other tribes like Mande (also found in Guinea & Mali), Gurma (also in Northern Ghana), the nomadic Tuareg (who also live in Niger, Mali, Algeria, & Libya), and the seminomadic Fulani (also in Nigeria, Senegal, Guinea, and other countries). As of 2024, the average age of the Burkinabe population is 17 years old. The country is 65% Muslim, 25% Christian, and the rest practice indigenous beliefs.

With a population of 24M people, comparable in size to New Zealand or Colorado, Burkina Faso is the 9th least developed state on earth. Over 70% of the population are subsistence farmers, particularly in cotton cultivation , and 90% of the workforce is employed informally. Below you’ll see average Burkinabe incomes over time adjusted for inflation.

In 2022, the average Burkinabe farmer produced 1.2 tons of food per hectare, which is below the average for food deficit countries, 2.35 tones per hectare.

Part of Burkina Faso's low productivity is due to challenges such as tsetse flies, locusts, reliance on rain for irrigation, and radical terrorists killing farmers since 2015. As of May 2024, Burkina Faso has the 7th worst credit rating in Africa, with its bonds classified as “junk”. Roughly a quarter of Burkina Faso’s budget relies on foreign aid, and the country has experienced eight successful coups. Due to an ongoing jihadist insurgency, the only government controls 40% of the country.

In my parent’s country, Ghana, when you go North, you’ll see that many Burkinabe risk their lives coming to Ghana to escape terrorism or militias.

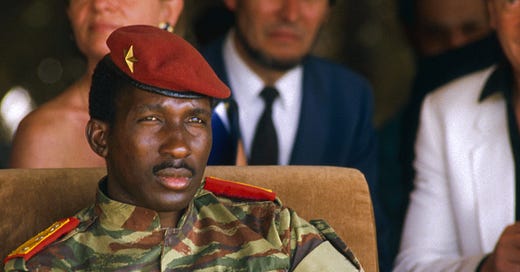

Burkina Faso means “Land of Incorruptible People” or “Honest Man’s Country”. Burkina is Mossi for “Upright” and Faso is “homeland” in Dioula/Malinke. One of Africa’s most beloved African leaders, Thomas Sankara, renamed the country from the colonial name, Upper Volta, in 1984. Previously, the country was known as Upper Volta due to its location atop the Volta River.

Burkina Faso’s Resources

Burkina Faso heavily relies on gold exports, similar to Niger and Mali. It ranks 12th in the world for gold mining production and 20th for gold exports. Mining, particularly gold, accounts for over 80% of Burkina Faso’s foreign exchange earnings and approximately 20% of its national budget. Most of Burkinabe gold is sold to Switzerland.

One of the largest industrial miners in Burkina Faso is the Swiss firm, Metalor Technologies International, alongside Canadian, Russian, and Australian firms. These foreign companies typically engage in joint ventures with the Burkinabe government. Foreign firms usually own the majority of the mine, bringing in capital, technology, and expertise, while the Burkinabe government owns at least 10% of the mine and collects royalties and taxes from production.

Unfortunately, like Mali and Niger, gold is not as lucrative for Burkina Faso as oil is for Gulf States. In terms of distribution of resource revenue, Burkina Faso earns roughly $300 per person from gold, while the UAE generates over $10,000 per person from crude oil and gas exports.

Burkina Faso has no sovereign wealth fund like Gulf States do, and the country almost always buys more abroad than it sells every year. Look at the current account deficit of Burkina Faso below:

Due to terrorism in the Sahel, extremists in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger have been running illegal gold mines to fund their activities. Additionally, artisanal miners also smuggle gold. There are over 600 artisanal mining sites in Burkina Faso, extracting about $2 billion in value annually. The Office of Mines and Geology requires all gold to be registered at a trading house, where it is taxed at least 3%, depending on the amount. Some miners evade these taxes, depriving Burkina Faso of much-needed revenue.

Burkina Faso's main export wasn't always gold; for a long time, it was cotton, managed by firms like Sofitex, Faso Coton, and Socoma. Increased foreign investment attracted multinationals searching for gold, and since 2009, gold has become Burkina Faso’s biggest export. Burkina Faso benefited from the gold boom until 2012. Gold prices crashed until 2020.

Regarding infrastructure, the country's electric utility cannot meet demand, resulting in the importation of approximately 70% of its electricity from Ivory Coast and Ghana.

As a landlocked country, Burkina Faso faces additional costs for using coastal ports and dealing with poor road conditions. It relies on Ivory Coast, Togo, and Ghana to export gold and cotton.

Burkina Faso likely has substantial reserves of other resources, such as zinc and manganese, but currently exports less than $200 million worth of these combined due to insufficient technology and foreign capital for extraction. Net Foreign direct Investment (FDI) flows (inflows - outflows) are very low in Burkina Faso, never exceeding $1B since independence. In some years, Burkina Faso’s neighbors receive more than 10x the FDI that Burkina Faso attracts.

Pre Colonialism: The Mossi Kingdoms (1000 AD-1896 AD)

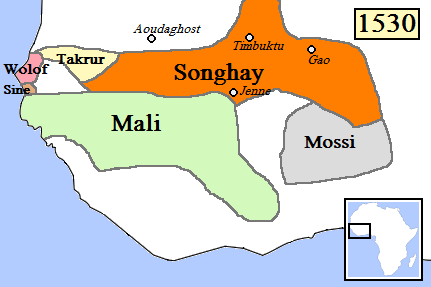

Before a country called Burkina Faso even existed, various tribes inhabited different regions: the Peul or Fulani in the North, the Gourma in the east, the Bobo & Lobi in the West and the Mossi in the center. The Mossi Kingdoms were the developed polities inside the Modern Borders of Burkina Faso. The Mossi Kingdoms, ruled by kings, or "Naba," had a structured caste system comprising nobles, warriors, and commoners. Prominent kingdoms included Ouagadougou (waga-DOO-goo), Tenkodogo (ten-ko-DOH-go), and Yatenga, which are now cities or provinces.

The Mossi traditionally worshiped their ancestors, but through trade and war with the Mali Empire, Islam began to spread. They traded gold and people with other Africans and Arab-Berbers. Despite attempts by the Mali and Songhai Empires, they failed to conquer the Mossi Kingdoms. The Mossi remained independent, although the Songhai & Tuareg conducted raids to capture Mossi people, selling them to Arabs in the Trans Saharan trade and the Portuguese in the Transatlantic slave trade. The Mossi survived by developing cavalries and trading with other empires like the Ashanti and Hausaland.

By the 1800s, Songhai Empire was long dead, but the Mossi Kingdoms continued to face challenges from other African empires like the Fulani Sokoto Caliphate, the Mande Kong Empire, and the Fulani Macina Empire. The Mossi were further weakened by famine and internal civil war. By the time France arrived, the Mossi states were already significantly weakened by these conflicts.

French Colonialism: Upper Volta (1896 AD- 1960 AD)

After the Berlin Conference, France claimed most of West Africa. In 1895, France negotiated making the Mossi Kingdom, Yatenga, a protectorate, but then forcefully annexed the Mossi Kingdom of Ouagadougou in 1896. By 1898, French explorers had coerced local Kings into signing treaties, solidifying French control in the Gourma, Bobo, Lobi, and Gurunsi regions. (The Lobi tried fighting back with poison arrows but failed. The French kidnapped their women, children, elders, seized livestock, burnt villages, and destroyed their crops to subdue them.). By 1898, these separate regions were merged into Upper Volta, solidified by an agreement with Britain that separated British Gold Coast (Ghana) from French Upper Volta (Burkina Faso). The region was incorporated into French West Africa, with Dakar, Senegal, as the capital.

France ruled indirectly, relying on traditional Mossi chiefs due to a shortage of European staff in French Upper Volta (Burkina Faso). If a traditional leader was non-compliant, France would appoint a new chief.

Initially, Upper Volta was part of Upper Senegal-Niger along with Soudan (Mali) and Niger. The colony's borders changed frequently, sometimes merging with Mali, Ivory Coast, and Niger. Famines occurred, such as in 1908 and the locust-induced famine of 1928. Rebellious chiefs were often killed, and Tuareg Amazigh nomads resisted French rule. France ended domestic slave practices, such as “pawning”. Pawning is a traditional West African practice where a poor family sends a child to work for another family or merchant in exchange for credit, goods, or services. The kid is basically used as collateral to secure a loan or pay off a debt. There’s exploitation, abuse, and denial of the kid’s education. France banned pawning, and imposed a forced labor, where people worked on infrastructure projects and grow cotton and groundnuts for ripped clothes and beads as “payment”. The harsh conditions led to the Volta-Bani War (1915-1917), where 20,000 rebels died trying to end French rule.

Catholic missionaries were introduced, but Fulani Muslims and Animist Mossi largely rejected Catholicism. Thus, Christianity remains a small part of the Burkinabe population. Some families practiced Christianity, Islam, and Animism simultaneously.

Post-WW2 Reforms:

Econ Reforms: After WWII, France reformed its colonial governance, branding it a "civilizing mission." In 1947, the Mossi Kings lobbied for Upper Volta to be separated from Ivory Coast, which France approved. France increased investment through the Investment Fund for Economic & Social Development of Overseas Territories (FIDES), building roads, hospitals, schools, hydraulic works, and agricultural research institutes. Examples of infrastructure include the Abidjan-Ouagadougou railway, which transported Upper Volta’s cotton to Ivory Coast’s coast.

Economic productivity was imbalanced in French West Africa. Coastal colonies like Ivory Coast and Senegal were relatively successful, producing 91% of exports, while hinterland colonies like Upper Volta (Burkina Faso), Soudan (Mali), and Niger were poor, relying on subsidies for 90% of their budget. Upper Volta mainly served as a labor reservoir for Ivory Coast, and it was one of France’s poorest colonies. See graph below:

Political Reforms: After WWII, France ended forced labor and established the French Union, granting Africans political representation in the National Assembly in Paris. In 1956 “loi cadre” (framework law) introduced universal suffrage, the electoral college, and territorial assemblies in the colonies, making them responsible for their own budgets and civil services.

A debate emerged between “territorialists” led by Félix Houphouët-Boigny, which separates each colony, and “federalists” led by Leopold Senghor who wanted French West Africa as one unit. Felix won.

By 1958, Upper Volta and other African colonies had to choose between leaving the French Union and lose French aid or remain. Upper Volta and most colonies chose to stay, while Guinea opted to leave.

In 1958, two significant movements emerged in Upper Volta: the Labor Unions and the Mossi Kings. The labor unions formed the African Democratic Rally, aiming to create a leftist state. The Mossi Kings attempted a coup in the colony to establish a monarchy but failed. Both groups were suppressed by Maurice Yaméogo, the "founding father" of the nation, who made the state a one party system before the state was independent.

The Pan Africanism Attempt:

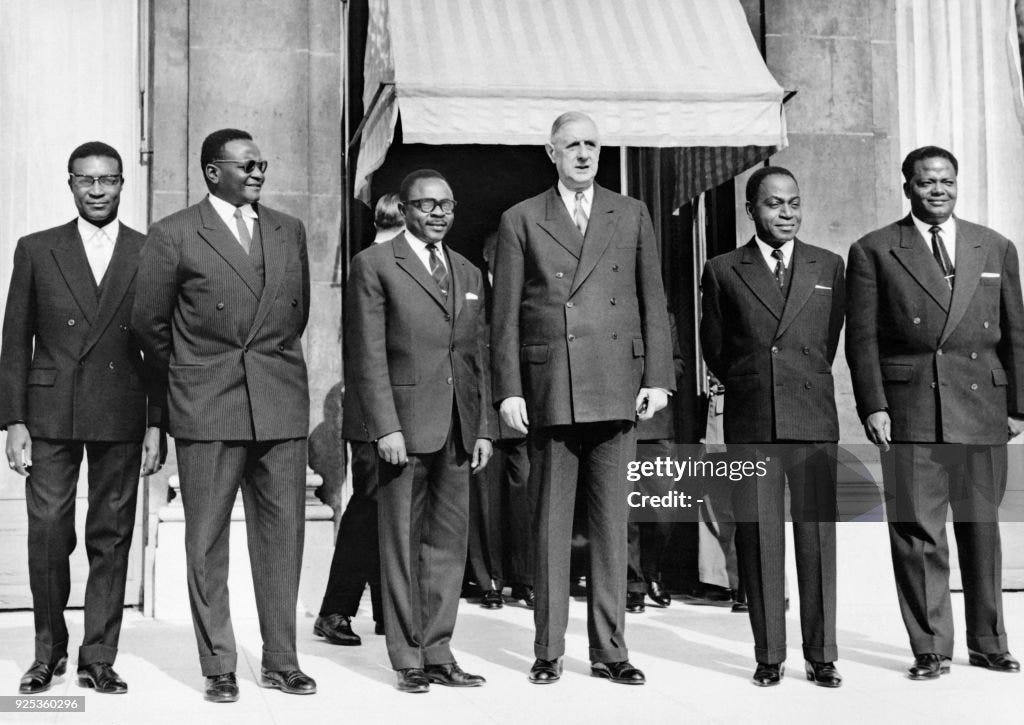

By January 1959, former colonies sought independence instead. Soudan (Mali), Senegal, Dahomey (Benin), and Upper Volta (Burkina Faso) planned to unite as the Mali Federation to achieve independence. However, Ivorian President Felix Houphouet-Boigny opposed this. He collaborated with French President Charles de Gaulle to bribe Yaméogo of Upper Volta to withdraw from the Mali Federation. The Mali federation eventually failed anyway.

Instead, Yaméogo joined this very loose federation called the “Conseil de I’Entente” with Niger, Ivory Coast, and Dahomey (Benin). French Black Africa became independent in the 1960s.

This union allowed Upper Voltarians to work more easily in Ivory Coast, where wages there are higher. In addition, the Ivorian president facilitated naturalization and citizenship for these mainly Muslim migrants, a factor that later contributed to Ivory Coast’s civil wars, when later Ivorian Presidents isolated Muslims when they created the exclusionist nationalism of "Ivoirité".

Independent Upper Volta

Maurice Yaméogo (1960-1966)

At independence, Upper Volta was, and remains, very poor. Agriculture and livestock accounted for 90% of employment and exports.

Social Changes: Since the Mossi chiefs attempted to oust him, Maurice Yaméogo stripped their power. (Maurice himself was a Mossi). He initially expanded the number and salaries of civil servants, invested heavily in rural schools, and developed more educational and government buildings. His government was also very corrupt, with his relatives and wife raiding government funds to buy villas, spend on luxurious spas, fur coats, and sports cars.

Economic Changes: Being landlocked and underinvested in agriculture, Upper Volta’s economy stagnated. The country relied almost entirely on cotton from the state-owned enterprise SOFITEX and cattle raising. Yaméogo's state-run marketing boards paid farmers a fraction of international prices.

International Relations: Yameogo, like many post-independence French African leaders signed a deal with France for subsidies, aid, multinationals, the CFA Franc, and a civil service staffed with many French nationals. Frenchman named Andre Aubaret owned the hotels, real estate, telecommunications and small industry in the country. Also, despite trying to befriend them, Yameogo did not get along with the Pan-African Socialists (e.g. Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Ahmed Sekou Touré of Guinea). After Touré called him a puppet of France, Maurice called Touré a “bastard of bastards” and distrusted Nkrumah for his perceived expansionist ambitions.

Riots & Overthrow:

In 1965, reduced French aid led Yaméogo to implement an austerity budget, cutting government workers' salaries, raising taxes, cut pensions, and eliminating family allowances and educational subsidies that made private Catholic schools affordable. The declining economy, reduced benefits, Yaméogo’s corruption, and increased taxes led to widespread discontent.

In 1966, strikes and riots erupted in Ouagadougou, involving unemployed workers, religious leaders, urban dwellers, students, labor leaders, and government workers. The populace called on the military to overthrow Yameogo.

Yameogo asked the military to arrest the protestors, but they refused. Realizing he had lost control, Yaméogo resigned, handing power to army commander Sangoulé Lamizana.

Sangoulé Lamizana (1966-1980)

After ousting Maurice Yaméogo, the military under Sangoulé Lamizana initially enjoyed widespread popularity among the church, chiefs, labor unions, elites, and urban classes, who viewed Yaméogo as a corrupt French puppet. He was originally a military ruler that then won elections. One of Lamizana's first actions was to confiscate the property of Yaméogo's supporters and reveal that Yaméogo had embezzled $1M from the state treasury.

Austerity: Despite his popularity, Lamizana continued Yameogo's austerity measures, which included firing civil servants, implementing a 10% wage cut for civil service workers, ending housing allowances for government workers, reducing Catholic school subsidies, and increasing taxes under the guise of "patriotic contribution."

Social & Development Changes: Lamizana partially restored the authority of traditional chiefs and expanded his support among priests and imams. He worked with the World Bank to fund various projects, such as improvements in telecommunications and agriculture.

The Three Big Challenges Faced:

Issue #1, Drought: From 1968-1974, a devastating drought struck the Sahel, severely impacting agriculture in Upper Volta and causing widespread starvation. Western aid was rushed in by airlift, but military officers stole some of the food aid and sold it to neighboring countries in the ”Watergrain scandal”. The Tuareg Amazigh suffered the most and voiced their complaints to the government.

Issue #2: Oil Crisis: The Arab Oil cartel launched an embargo and reduced oil production following the Yom Kippur War, leading to a 500% increase in real international oil prices, draining Upper Volta’s reserves and forcing the country to borrow to buy oil.

Issue #3: 1974, Border Skirmish with Mali. Malian leader Moussa Traoré sought control of the Agacher Strip, believed to be rich in resources like manganese, gas, titanium, and uranium. Lamizana defended the border, though these resources remain largely unconfirmed.

Nationalization program & Socialism: In 1975, Lamizana announced a "Voltaization" program, requiring French firms to relinquish 49% ownership to the Upper Volta government. He established state-owned enterprises and joint ventures with French firms to promote cotton (SOFITEX) and sugar cane (SOSUCO) production. Attempts to manufacture bicycles, motorcycles, and textiles under state management failed. Using cotton revenues, he also tried subsidizing Upper Voltaic merchants but internal growth was hampered by the limited purchasing power of subsistence farmers and low global demand for Upper Voltaic products.

Military-Civilian economy: In 1974, he suspended the constitution and placed all government departments under military prefects. The military was supposed to build projects, but instead, officers looted funds, pilfered food aid, stole building materials and sold them abroad.

Seeking aid: In 1979, Lamizana secured increased aid from Europe, securing $116 million, which accounted for 70% of Upper Volta’s budget.

Labor Unrest: In 1975, after Lamizana established a one-party state, labor unions organized a nationwide suspension of economic activity — streets deserted, stores shuttered, and stores were empty. In 1977, there was another strike by teachers & medical specialists, which required military suppression. By 1978, elections were allowed again. By 1980, grain production decreases led to higher prices and widespread starvation, affecting both people and livestock. Discontent by labor unions erupted again, which culminated in a military coup led by Saye Zerbo.

Saye Zerbo (1980-1982)

Corruption was so rampant… How do we know this? Future President Thomas Sankara, as head of the information ministry, encouraged journalists to investigate corruption and abuses of power. Zerbo did not like this, so he weakened the information ministry’s power.

The economy was deteriorating again. You know what that means by now. The labor unions demanded more pay again and a freeze on food prices., prompting Zerbo to suppress them.

Sankara, disillusioned with Zerbo's government, resigned and spoke out against it, resulting in his imprisonment.

The unrest continued as civilians, workers, civil servants, and teachers went on strike. Zerbo responded with arrests and beatings while enriching himself and his clique, further alienating the military. He was couped after two years of rule, Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo overthrew Zerbo.

Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo (1982-1983)

Jean-Baptiste, a pediatrician, took over, took over and appointed Thomas Sankara as Prime Minister.

In 1983, Sankara's meeting with Muammar Gaddafi for potential economic cooperation put him on America and France’s radar, though Sankara later denounced Libya's intervention in Chad and initially rejected Gaddafi's aid.

Sankara condemned Israel’s invasion of Lebanon and America’s interventions in El Salvador and Nicaragua at the UN. After his speech, he toured and befriended many communists and populist leftists like Castro of Cuba, Kim Il-Sung of North Korea, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua, Jerry Railings of Ghana, and Samora Machel of Mozambique. The CIA called Thomas Sankara and his neighbor Jerry Rawlings of Ghana “Tom and Jerry” as they were both viewed as potential tools of the Soviets and Gaddafi (they weren’t).

Mitterrand encouraged Ouédraogo to remove the leftists in his administration. So Ouédraogo removed the pro-Libya, anti French members of his government. Ouédraogo removed Sankara initially in 1983.

Civilians (unemployed people, traders, urban workers, students, etc.) protested the arrest of Prime Minister Sankara during a drought.

“We mobilized when we heard that they were going to kill Sankara… We were all united. Sankara was our symbol.” — A city dweller protesting for Sankara.

Burkina Faso was on the verge of a revolution. Both Gaddafi and Rawlings were sending arms to military officers in Burkina Faso to overthrow Ouédraogo.

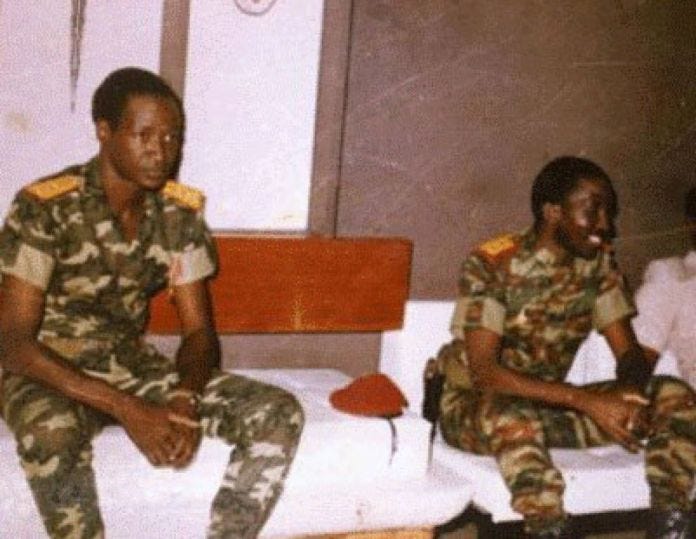

Ouédraogo released Sankara to stop the protests. But then Ouédraogo arrested Sankara again. To end his feud, Sankara’s best friend & future president, military officer Blaise Compaoré freed Sankara.

Eventually, Thomas Sankara and his buddy Blaise Compaoré overthrew Ouédraogo. Part 2 will be all about these two.

Actually Sankara has become very popular on Chinese internet in recent years. I give the credit to a history video maker “小约翰可汗”. He made a lot videos introducing history of different African nations. The one talking about Burkina Faso received 14 million views and 29 thousand comments. Here’s the link:【非洲的切格瓦拉是谁?【奇葩小国25】-哔哩哔哩】 https://b23.tv/XGAPLT9

In the early years there seems be an underinvestment in agriculture but premature investment in schools and hospitals. Seems to be a trend for post ww2 African leaders. Did the French manage to set up a functional legal system with land titles while they doing "benevolent" imperialism.