The Economic & Geopolitical History of Equatorial Guinea

A Country which Shows why you have to dig deeper than GDP Per Capita Numbers

Background on Equatorial Guinea

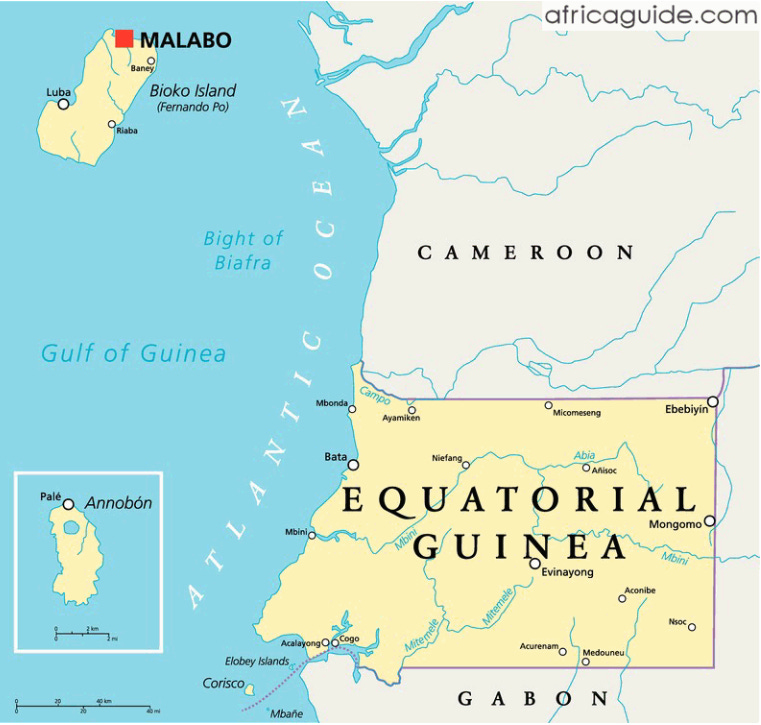

Equatorial Guinea, a Spanish speaking Central African country of 1.7 million people is slightly smaller than Maryland. It has two main regions:

1. Mainland Equatorial Guinea or “Rio Muni”, where 70% of Equatorial Guineans live is mainly consisted of poor, subsistence farmers except the costal city and commercial capital, Bata.

2. The islands, the largest called Bioko which has a relatively high human development index (a composite score of health, income, and education) that exceeds South Africa, Morocco, and most of Africa. The de facto financial and political capital is Malabo on Bioko Island. The other islands are Corisco, the Elobey Islands, and Annobón.

The government is in the process to move the capital to a new city called Ciudad de la Paz (also known as Oyala) in the mainland. The nation consists of diverse tribes, with the Fang tribe dominating the mainland (85%) and the Bubi predominately on Bioko Island. Other significant tribes include Kombe, Mabea, and Lengi.

The government doesn’t invest enough in rural development, which prompts rural-urban migration, resulting in stagnant agricultural productivity. Much of the country is controlled by government owned enterprises controlled by the family. This huge rural-urban divide makes the country deeply unequal.

The country is deemed authoritarian and corrupt by the West. The nation has only had two presidents from the same Nguema family. The current President wins over 93% in each election.

Equatorial Guinea is a petrostate like Gabon, Angola, Libya, and Nigeria. Below you can see that oil & gas make up 90% Equatorial Guinea’s exports and also its government revenue.

Relying heavily on the oil sector, Equatorial Guinea's economy revolves around oil and gas, complemented by industries such as finance, government employment, and construction.

Mainland underdevelopment, apart from Bata, contributes to Equatorial Guinea's low life expectancy below 60 years as of 2023, and a lower human development index than Sao Tome, where Equatorial Guineans earn over double their incomes. What helps Equatorial Guinea compared to other African petrostates is its relatively large oil reserves and its high annual oil production for its tiny population. You can see Equatorial Guinea’s stats compared to its land & maritime neighbors below:

A small aside about GNI or GDP per Capita

Gross Domestic Production (GDP) or Gross National Income (GNI) per capita is a useful measure indicating average citizen earnings. However, it overlooks distribution disparities.

For instance, in Equatorial Guinea, based off the World Inequality Database (WID), the top 10% earn 51.4% of the income, the middle 40% earn 37.4%, and the bottom half earn 11.2%.

In 2022, the country had a population of 1.67M and a total national income of $8.91 Billion, that means the average Equatorial Guinean makes $5150 per year, placing it in the World Bank upper middle income bracket. Despite being considered poor by Western standards, this nation would rank relatively high among African countries, slightly surpassing the income of most North African nations as well as some Middle Eastern ones Jordan & Lebanon.

However, because of the nation’s distribution that means the top 10% make roughly $27,360 a year, resembling the average income in Portugal. The middle 40% make roughly $5000 a year, akin to Lebanese, and the bottom half make roughly $1190 a year, which is poorer than Haitians.

This checks out since 56% of Equatorial Guineans are employed in farming, specifically sweet potatoes, plantains, and bananas, alongside fishing and goat herding. The farmers are subsistence farmers that face food shortages as it imports nearly 700x more food than it exports, with exports totaling roughly $300K.

The United Nations and African Development Bank, make stronger estimates on income inequality than WID does. These institutions estimate that roughly 70% of the population lives in poverty. It’s healthcare services are below average for a country at its middle income level.

History

The original inhabitants of mainland Equatorial Guinea, where Ndowe people and pygmies. In around 1000 BC, Bantu people from present-day Cameroon and Nigeria settled mainland Equatorial Guinea. The Fang, among others, predominantly inhabit the mainland, while the Bubi, also Bantu, inhabited Bioko Island.

Portuguese Exploration

Around the 15th century, Portugal discovered the island, Bioko (then called Fernado Po, named after the explorer, Fernado Po) and tried to enslave the Fang. However, diseases like yellow fever and malaria killed Europeans, enabling the Fang to resist enslavement. Instead, Fernando Po/Bioko Island became a coastal checkpoint of slaves from other regions of the West African “slave coast”.

Colonial History

Around 1778, Portugal sold the territory to Spain in exchange for Spanish territory to be incorporated into Portuguese Brazil —Treaty of El Pardo. But, just like the Portuguese, Spanish conquest was thwarted by yellow fever, leading to their withdrawal in 1781.

By 1800s, yellow fever already had treatments. Spain was able to slaughter the Bubi population of the island and invest in agriculture. This led to a spike in cocoa production. Spanish citizens migrated to Fernando Po/Bioko Island and forced Spanish Guineans to work on sugarcane, cocoa, and coffee plantations in Bioko and Annobon. Since there wasn’t enough Spanish Guineans, Liberia and Britain also made a deals with Spain to put their workers in Spanish Guinea for farm work. Meanwhile on the mainland, Spain had to send in troops to suppress Fang revolts in the 1920s.

Spain weakened after their civil war, Spain became Fascist under Francisco Franco. Also, there was a wave of independence movements post WW2. So Fascist Spain tried to do more to maintain their colony.

By 1959, Spanish Guinea upgraded from colony to Spanish province, offering more political freedoms to Bubi islanders, invested in African education and social programs. During this time, the Prime Minister of Spanish Guinea, was Bonifacio Ondo Edu. Thanks to Bonifacio’s leadership, Spanish Guinea became the 5th highest producer of Cocoa in Africa and was one of the most developed African colonies.

However, most of the economic growth was taking place with the Bubi tribe in Fernando Po/Bioko Island. The mainland Fang people in Rio Muni were significantly poorer (still true today).

By 1963, many Spanish Guineans went to the United Nations Decolonization Committee to form political parties and lobby for the right to self-determination. Fascist Spain tried brutally suppressing the political parties by killing, exiling, and imprisoning political leaders. But none of this could stop the wave of African independence. By 1963, Spanish Guinea was renamed Equatorial Guinea.

Independence

In the end of the 1960s, the United Nations pressured Fascist Spain to hold a national referendum on Equatorial Guinea. In 1968, 64% of Spanish Guineans voted for independence.

In the first election there were two Fang tribe candidates:

Francisco Macias Nguema, a “radical” charismatic civil servant who told people what they wanted to hear.

and

Bonifacio Ondo Edu, the former “moderate” Prime Minister of Spanish Guinea who led Equatorial Guinea to independence.

63% voted for new leadership under Francisco Macias Nguema. Bonifacio died the following year.

Francisco Macias Nguema (1968-1979)

Macias called himself a “Hitlerian Marxist” and immediately killed, banned, or arrested political opposition.

In 1969, some Equatorial Guinean rebels tried to remove Macias with Fascist Spain’s help, but Macias crushed the attempted coup.

The Making of an African Pol Pot:

Reign of Terror (1971-1979): Following an attempted coup, Macias grew increasingly paranoid. Macias abolished the constitution and made himself president for life. He made four security forces: the Youth based “Youth on the March with Macias” (based off Hitler Youth) , the National Guard, the Militia, and the JMM which perpetrated violence, imprisonment, murder, and surveillance. He also controlled tightly controlled press to prevent dissemination of negative info.

He imprisoned intellectuals, created a personality cult, burned villages, and massacred Bubi people and antagonized 60K Nigerian migrant workers. He terrorized the Spanish who did most of the entrepreneurial, technical and managerial work, causing a mass exodus of Europeans (7000 Spaniards) and 500 Spanish firms. Roughly 100K of Equatorial Guinean’s 300K population either died or fled to neighboring African countries or Spain. Marcias infamously burned fishing boats and placed mine explosives on roads to prevent people from escaping the country.

Forced Labor: In 1976, he enforced compulsory labor, coercing citizens over 15 years old and criminals to toil on government plantations, construct roads, and work in mines. — over 25K Equatorial Guineans were forced into unpaid labor, compensated in forms of rice, palm oil, and fish rations.

Nationalization of Industry: He also nationalized previous Spanish owned plantations and mines, but mismanagement ensued.

Opened Relations with the Communist Bloc: Macias allowed the Soviet Union & Cuba to use Malabo as a strategic base to support communists in the Angolan civil war. Russians and Belarussians were given high quality fish and in return the Soviet Union gave scholarships to Equatorial Guineans and build their airports. Mao of China and North Korea provided arms to the Equatorial Guinean military force and made roads.

Opened Relations with the France: Equatorial Guinea allowed French firms to find uranium in mainland Equatorial Guinea in exchange for aid.

Corruption: Macias killed the head of the Central Bank and held control of the government’s treasury. The international criminal court found that Macias stole millions. Macias kept a large portion of foreign reserves in a bamboo hut in his personal garden.

Deterioration of services: Poverty, Illiteracy, and disease rose under Macias. 90% of public services—including electric, mail, and transport stopped operating. He had a program of “African Authenticity” where he banned Catholicism, Western medicine, tomatoes, sugar, and milk calling them “un-African”.

All these actions reduced Equatorial Guinea’s cocoa, timber, and coffee production and exports, depleting Equatorial Guinea’s much needed foreign currency and hurting its economy.

Declining cocoa and coffee exports (low demand for Equatorial Guinean currency: Ekpwele) alongside the necessity of importing food, medicine, fuel, and manufactured goods (high demand for US dollars) triggered a balance of payments crisis and inflation. The devaluation of the Equatorial Guinean epkwele to the dollar due to low demand led to increased import costs and inflation in the country.

Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo (1979-Present)

Nguema was deposed and executed by his nephew, Teodoro Obiang who has ruled for 40+ years.

Plotters tried to remove him in 1980, but he unlike his uncle, he didn’t declare war on his country. Obiang made changes to the government: schools were reopened, energy accessibility improved, and etc. Albeit, the country is still far from a Western liberal democracy.

Equatorial Guinea, was suffering from both a balance of payments crisis and inflation. In 1980, he took out Equatorial Guinea’s first IMF loan for $5.5M. In 1983, Nguema deliberately adopted the Central African CFA franc, which coupled with decreasing oil prices after the Iranian oil crisis of 1979, tamed inflation in his country. In addition he joined the French Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa along with Cameroon, Central Africa Republic, Chad, Gabon, and Congo-Brazzaville.

In 1985, 1988, and 1993, he took more loans for $5.4M, initiated a $9.2 million structural adjustment program, and obtained a $4.6M loan respectively in order to secure foreign currency, address fiscal issues, and fund oil exploration from Spanish, French, and American oil companies. As he was borrowing this money, the IMF successfully persuaded him to allow elections again the 90s.

Government owned corporations:

His oil bet paid off. Due to structuring an oil exploration deal with the American firm Exxon Mobil, in 1996, Equatorial Guinea discovered oil right outside of Bioko Island in the off-shore Zafiro oil field. Also in 2002, Obiang made a government owned oil company, called Guinea Equatorial Petrol (GEPetrol) under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Mines, Industry, & Energy.

He also made state owned firms in electricity (SEGESA), airlines (Ceiba Intercontinental), and in fishing, telecom, and energy like oil.

In 2007, natural gas was found by American firms Hess and Marathon. Equatorial Guinea made another government owned firm called Sonagas and invested with U.S. Marathon Oil, Japanese Mitsui & Marubeni to make a joint venture named EG LNG to extract liquidified national gas. The country was flooded with foreign direct investment from 1996-2013 Both America and China competed to ensure Equatorial Guinean’s oil shipments are protected from West African piracy. Government revenues increased from $2 million (1993) to $4 Billion (2009). Economic growth exploded due to hydrocarbons (mainly for the elite and politically connected). Pre-oil & gas discovery, the average Equatorial Guinean made $425 a year (inflation adjusted). After oil discovery and at near peak oil prices, average Equatorial Guineans made almost $18,000 a year, though income distribution remained highly unequal. Lastly, Equatorial Guinea created a sovereign wealth fund of $166M (as of December 2023).

If you have paid attention to my articles in Angola and Gabon, then you know that state-owned oil firms have been black boxes for corruption for eroding a line of separation between government ministers and enterprise executives. In 2018, the U.S. Department of Justice jailed oil executives for bribing Guinea Equatorial Petrol officials for over $15M. America, Switzerland, South Africa, and France have confiscated and auctioned off millions of money laundered assets like Malibu & Paris Mansions, super yachts, and luxury cars from the Equatorial Guinean government.

The oil industry in Equatorial Guinea is capital-intensive, relying more on machinery and automated technology than human labor. Employment in this sector is highly specialized, involving engineers, geologists, and technicians for equipment maintenance in extraction and refining processes, making it a limited job creator. AKA, oil doesn’t make jobs.

Mega Infrastructure & Construction:

From 2005-2015, the Equatorial Guinea government had a ridiculously high rate of infrastructure and construction investment in itself. (African average: 20%, Equatorial Guinea peaked at 54%!). There’s many new hospitals, sports stadiums, hotels, and highways in Malabo and the port city of Bata. Most of the labor is employed using Chinese, Malian, or Senegalese workers instead of locals.

Chinese, Middle Eastern and European firms help out making the new infrastructure and buildings. China’s Export-Import Bank and the Industrial & Commercial Bank of China have lent funds to make the Port of Bata, submarine cable systems, and the Djibloho Hydropower plant.

But much of this was construction corruption and “prestige projects”. Imagine the government knows a hotel will take $15M to build, the government minister can tell a government inspector to say the price is $35M, to pocket the difference ($20M). Also, despite all this investment there’s still a lack of railways.

Examples of this in Equatorial Guinea are empty villas, a 156 bed hospital that is under utilized, a massive six line highway on Bioko Island that locals hardly use, $400M Italian built hotel that sometimes has no guests, a brand new international university, and a national cathedral.

The oil propelled Equatorial Guinea to almost catching up to European nations like Hungary or Poland, until global oil prices collapsed in 2014.

The global oil price collapsed due to:

The U.S. shale revolution massively boosting oil & gas (increasing supply).

China shifting from an export-focused to a domestically-driven economy, which meant slower growth (decreasing the rate of increase in demand).

The oil price drop was so damaging that many oil states stagnated or declined after 2014. Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, UAE, Nigeria had their incomes stagnate after 2014, and Venezuela just collapsed and stopped recording economic data. Equatorial Guinea’s government revenues dropped and many construction developments went unfinished. The country is also facing issues with education & healthcare spending.

In 2012, the average Equatorial Guinean made $15.5K a year, inflation adjusted (incomes are heavily skewed towards the rich), but by 2022, the average Equatorial Guinean made $5.32K a year. (See Inflation Adjusted Income Graph above).

In 2017, the nation joined the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). However, crude oil production is less than half of what it was in 2017:

Finance:

Equatorial Guinea has been trying to finance its development not just with oil revenues but through bank lending. Unfortunately, since many of the hotels don’t have guests, universities aren’t flocked with students, and highways aren’t collecting enough tolls, many of Equatorial Guinea’s bank loans are non performing. This was ok when oil revenues subsidized losses, but now that oil prices collapsed, non performing loans exploded. Over half of bank loans in Equatorial Guinea are non performing.

Equatorial Guinea’s banking sector has many non performing loans due banks lending to the government, and the government has been missing scheduled interest payments to bank. The government has been missing scheduled payments to Chinese, Middle Eastern, and European construction firms since oil prices plummeted. The government is drawing down on its deposits from the Bank of Central African States in Yaoundé, Cameroon to make payments to construction firms.

What is Equatorial Guinea’s Strategy to escape its rut?

I could tell you its government plan -Horizon 2020 , but I would rather tell you what the government was/is actually doing:

IMF rescue loans: The country has returned to needing rescue loans from the IMF due to the falling oil prices. When Equatorial Guinea found oil in 1996, it longer needed to borrow from the IMF. But starting in 2019, it needed emergency loans again. Taking IMF programs mean privatizing government owned firms. The government is strategically thinking about selling its state owned telecom, utility, and airlines to investors.

Extending crude oil exploration projects: American firm Kosmos Energy found more oil in the nation in 2019. Equatorial Guinea has then given extensions to oil & gas firms to look for even more oil.

Refining oil to petroleum products: The government is building new refineries to make diesel, gasoline, and jet fuel.

Developing More Liquidified Natural Gas(LNG): British energy firm, Ophir is working in Equatorial Guinea’s Fortuna’s gas fields, so Equatorial Guinea can make more money selling LNG to Britain, and Britain gets a more natural gas from a country that isn’t Russia. In 2021, Chevron exported its first LNG cargo from the Alen gas field in Equatorial Guinea.

Industry Diversification: Equatorial Guinea is trying to bring American, Chinese, South African, Brazilian, and Spanish investors to bring capital to its fishing, mining, tourism, and finance industry.

Conclusion

The Nguema family has governed Equatorial Guinea since independence for 55 years. The initial Nguema caused a reign of terror, leading to a coup by the current Nguema. The current Nguema ended inflation, increased reserves, and found oil benefiting a third of the nation.

The current Nguema is 81 years old as of December 2023. Will his likely successor & VP, Teodorin use the oil revenues to develop the mainland where most people live? Or will the country run out of oil before then? Equatorial Guinea is projected to be depleted of oil by the 2035 unless it can find more substantial reserves. The country needs to diversify from hydrocarbons, cut wasteful spending but easier said then done. Equatorial Guinea has roughly 11 years to develop or else even the elite of Equatorial Guinea will be in trouble.

This is a very interesting essay. I’ve always wondered how many of these small countries we can’t find on a map exist economically. It seems as though they exist as tennis balls bouncing between larger spheres of influence depending upon what sort of resources could be pilfered. I appreciate you getting into the details.