The Remastered History of Nigeria Part III: The Rise, Rule & Resistance of the Sokoto Caliphate

How a small group of religious devotees created an empire and got colonized

Previously…

Part I traced Nigeria's foundations from 1000 BC to 1100 AD, introducing the the Nok ironworkers, early Hausa settlements, the Kanem-Bornu, Yoruba, and Igbo. The article also gave a brief overview of modern Nigeria.

Part II explored medieval northern Nigeria (1000-1600 AD), when Kanem-Bornu and Hausa city-states became the commercial backbone of the Sahara trade network. They shipped slaves, kola nuts, and gold north to the Maghreb & Egypt while importing horses, steel weapons, and Ottoman firearms. Islam spread alongside trade, creating Africa's most literate societies outside the Nile Valley.

By 1600, three powers dominated the savanna:

Kano vs. Katsina – two Hausa powerhouses, constantly fighting for supremacy

Kebbi – a breakaway province from the former Songhai empire that muscled its way into Hausa politics.

Bornu – This polity was on its deathbed until the ascent of Idris Alooma. Under his reign, Bornu, flush with Turkish firearms, embarked on a relentless campaign to control and tax regional trade. Many Hausa states paid tribute to Bornu.

What This Article Covers

By the end of this installment, you will grasp:

The complex landscape of Northern Nigeria from the 1600s to the 1900s.

The profound reasons behind the emergence of the Sokoto Caliphate.

The mechanics of Northern Nigeria's eventual colonization.

Now, we continue our analysis with 17th-century Nigeria.

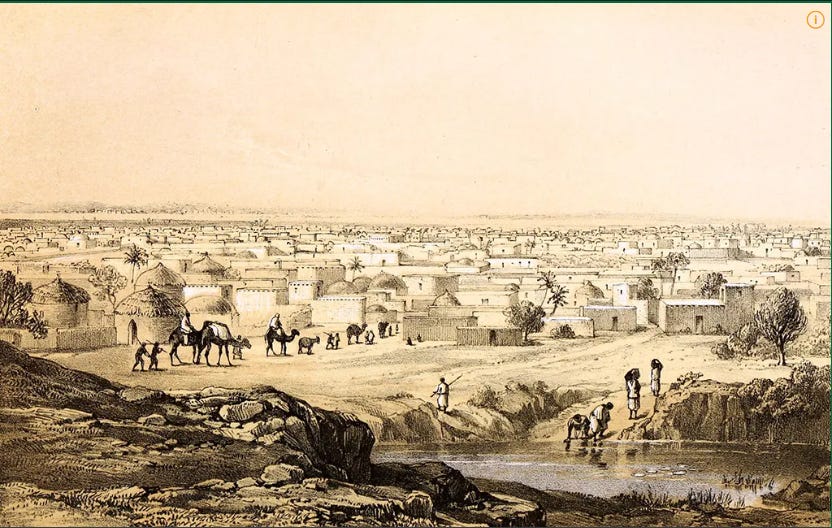

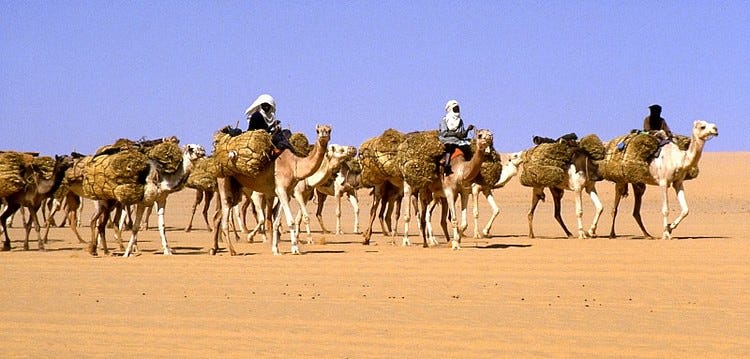

17th Century: Caravans, Conflict & Commerce

Imagine dawn breaking over the Sahara as Malam Ibrahim, a seasoned merchant, meticulously counted his human cargo for a final time. Three hundred camels stood poised for the arduous journey to Tripoli, but it wasn't gold or salt that would line his coffers. It was the 150 men, women, and children, shackled together, forming the desolate heart of the caravan. Jukun warriors, captured in last month's brutal raid. Nupe farmers, snatched from their burned villages. Children, their only transgression being in the wrong place when Kano's cavalry thundered through.

This was 17th-century Northern Nigeria, where the trans-Saharan slave trade was the throbbing, dark heart of the economy. Every chain that bound these captives was a link in a vast, intricate web of violence, politics, and commerce.

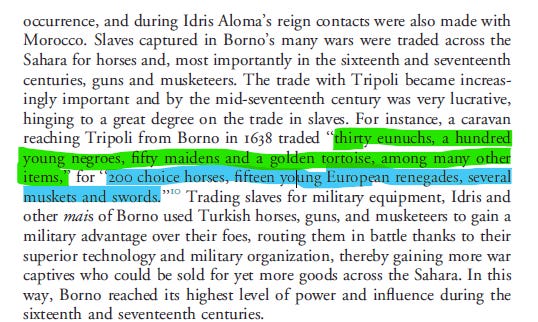

Here’s an example of a slave contract during this time:

Northern Nigerian states like Bornu bartered eunuchs, enslaved young men, and virgin young women—for muskets, horses, and, at times, even the services of European mercenaries.

Look below to see the rival states involved in Northern Nigeria:

Savanna Warfare: Calculated Chaos

We have many actors in Northern Nigeria. Here’s how I’ll categorize them, using mainly Hausa Chronicler categorizations:

The “Seven True Hausa” states – Kano, Katsina, Daura, Gobir, Rano, Biram, and Zaria.

The “Seven Bastards” – These “illegitimate states” involved two culturally Hausa states (Kebbi, Zamfara) plus five outsiders (Nupe, Yauri, Gwari, Jukun/Kwararafa, and Ilorin).

Bornu - The big polity

Igala, Nupe, Borgu - Middlebelt polities that are mainly raided for slaves

States like Gobir, Zamfara, Kebbi, Kano, Bornu, Zaria, Jukun, and Katsina fought less to annihilate their neighbors than to skim their tax base: toll a trade route, collect tribute, grab a batch of captives to sell north. Victory was measured in customs booths opened, not flags planted.

The balance of power shifted constantly. Zaria might extract tribute from Kano and Katsina for years, only to see the tables turn.

When costs rose too high—say, after decades of pillage by Bornu cavalry or Jukun archers—even Hausa arch-rivals like Kano and Katsina paused for a treaty so they could gang up on a common adversary. A great example was when both these states targeted the Jukun in the 1650s.

Weakness invited predation. States weakened by drought or dynastic infighting became irresistible targets. Bornu capitalized on Jukun’s famine and palace infighting to inflict crushing defeats in the 1680s, part of the broader decline that would reduce the once-mighty confederation to a tributary state by the 18th century.

The relentless toll of the tsetse fly on horses fueled this cycle of violence. As horses died off, states desperately needed fresh captives to trade with Arab-Berber merchants for replacement horses – a brutal economic necessity that perpetuated the raiding.

The constant warfare that had defined the 1600s would give way to deeper, more fundamental challenges in the decades ahead—challenges that would ultimately reshape the entire political landscape of Northern Nigeria.

18th Century : Reformers Rise, States Collapse

Seeds of Revolution

The 18th century marked a profound shift in Northern Nigeria, driven by five major developments:

Imperial Changes: Gobir emerged as the dominant Hausa power, conquering Kebbi and Zamfara during dynastic succession crises in the 1700s. While the losing states had dynastic succession issues, Gobir's armies seized their territories, with other Hausa states like Katsina claiming additional spoils.

Trade Reorientation: The flow of enslaved people dramatically reoriented. The European Trans- Atlantic slave trade increasingly overshadowed the traditional Arab-Berber trans-Saharan routes. Hausa and Bornu states were sellling more captives to Yoruba & Efik-ethnic intermediaries who sold slaves in coastal towns like Badagry and Old Calabar. These middlemen provided European goods in return: firearms, textiles, beads, and cowry shells.

Religious Issues: In much of West Africa at this time, Islam was widespread but shallow. At the time, Islam in West Africa was widespread but shallow. Conversion had spread slowly—via trade routes, traveling scholars, and gold-salt-slave networks—not by force. Most Hausa rulers practiced a syncretic form that blended Islamic law with local traditions: spirit possession ceremonies (bori), divination practices, matrilineal inheritance, non-Islamic marriage customs, harvest festivals honoring traditional deities, and shrine veneration. This syncretism maintained harmony, but drew sharp criticism from emerging reformist scholars.

Corruption: Rulers like Kano's Sultan Kumbari imposed arbitrary tax increases on grain, livestock, and clergy without warning. They silenced dissent by taxing, exiling, or executing critical scholars. Court appointments operated on bribery (called "gaisuwa"), with military and administrative positions purchased using pillaged goods rather than earned through Islamic learning or competence. The sarauta system—elective monarchy where councils of nine grandees could choose or depose Hausa kings—became clogged with patronage demands. Kings battled their own viceroys (Galadima) and treasurers (Ajiya) for control, while everyone demanded their cut.

Famine: Devastating droughts and famines in the 1740s-50s escalated market disputes into violent bread riots. Islamic scholars blamed Hausa rulers for neglecting the poor.

The Fulani Alternative

Amid this chaos, Fulani clerical families (also known as the Ulama) from Senegambia & Mali had quietly settled around towns like Alkallawa and Degel, establishing Quranic schools that attracted Hausa students. Fulani scholars condemned the corruption, laxity on Sharia compliance, and neglect of the poor. These pastoralist-scholars formed a literate Muslim minority distinct from both Hausa rulers and subjects—they paid special cattle taxes, avoided corvée (forced) labor, and recognized each other across state boundaries .Across the savanna, a wave of devoted Islamic clerics emerged in Nupe, Kano, Zaria, and Katsina.

One of the most prominent clerics was Shehu Uthman Dan Fodio, who called for tajdid (تجديد or renewal ).

The Inspiration: Futa Jallon & Turo

In 1790, Dan Fodio and other West African Muslim scholars called for renewal because they were inspired by other Fulani jihads like the 18th-century Futa Toro in modern day Senegambia and Futa Jallon in modern day Guinea.

Dan Fodio led the renewal movement in Hausaland. As Fulani polyglot scholar, he wrote extensively in Arabic and Fulani-Ajami on law, governance, and economics. Due to his intelligence, charisma, and oratory skills, he became profoundly convinced that Allah had chosen him as the mujaddid ( مجدد or renewer) for West Africa.

His mass following gave him real power — he successfully pressured Bawa, the Sultan of Gobir, to remove excess taxes because Bawa recognized dan Fodio’s popular influence.

This created a fundamental tension. Traditionally, Kings relied on scholars for legitimacy, and scholars needed royal stipends to survive. But this political alliance frayed as dan Fodio gained mass support and Hausa rulers became increasingly corrupt.

Bornu's Parallel Decline

The Kanem-Bornu Empire, once a regional hegemon, faced its own profound crisis under Ali ibn Dunama (1742-1792). From the west, Bedde and Tuareg raiders seized slaves and vital salt mines. From the east, Muhammad al-Amin of Bagirmi (1715-1785) launched aggressive attacks. Internal pressures mounted from large-scale migrations of Tubu, Kanembu, and Shuwa Arabs into Kanem, exacerbating grazing conflicts amidst prolonged famines.

As in Hausaland, Bornu's Muslim scholars openly blamed the Bornu rulers for corruption, tolerance of "paganism," and the pervasive mixing of local cults with Islamic practices. Many scholars abandoned Bornu, and crucial tributary states ceased paying homage, signaling the deep erosion of imperial authority.

The religious ferment, political corruption, and social upheaval that had been building throughout the 1700s would soon explode into revolutionary jihadist action.

19th Century: The Rise of the Sokoto Caliphate

By 1800, Fulani Islamic scholars had become the loudest critics of political corruption—a revolutionary break from traditional palace-aligned clerics.In response, in cities like Kano, Kings Sharif and Kumbari imposed new taxes and jailed scholars, fueling accusations of zalunci (injustice).

The Qadiriyya/Kâdirïyya Challenge

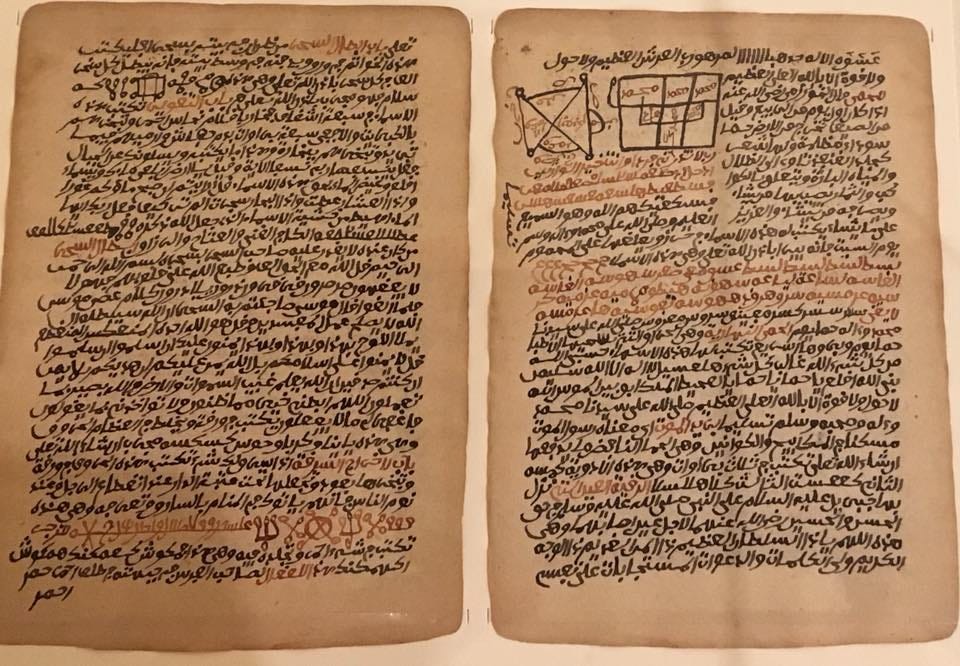

Dan Fodio's Torodbe family—part of a pan-Fulani clerical class—built a transethnic, literate network of Quranic schools, Ajami scribes, and Islamic judges. Funded by trade in manuscripts, ink, kola nuts, horses, and slaves, these scholars spread Islamic law across borders.

They continued to highlight the contradictions in Hausa Islam: Muslim rulers enslaved fellow Muslims, shrines and sacrifices to spirits persisted, and sharia law was ignored. From 1790-1802, dan Fodio traveled village to village across Hausaland, denouncing rulers' religious violations: oppressive taxes, disregard for Sharia, prohibition of Islamic dress (caps, turbans, veils), corrupt courts, and traditional idol worship. He urged Muslim communities to appoint independent judges, pay zakat to the Qadiriyya Sufi order, and stop paying tribute to rulers violating Sharia.

Initially, the reformers sought peaceful autonomy, founding self-governing communities on the fringes of Hausa states while negotiating exemptions from taxation and control over internal disputes.

The Point of No Return

As people and escaped slaves fled to these autonomous zones, local authorities watched their revenue and judicial power evaporate. Desperate rulers, like Sultan Bunu, attempted to reimpose control through force—raiding markets, confiscating livestock, and enslaving Fulani pastoralists.

This repression backfired spectacularly. Fulani herders, alienated by attacks on their communities and cattle, joined the reformers en masse, providing cavalry and manpower. More refugees fled to Qadiriyya settlements, hollowing out state authority.

In 1803, Yunfa ascended the throne of Gobir, restricted Fundamentalist Fulani religious preaching, ordered massacres of Fulani civilians, and attempted to kill Dan Fodio. This was ironic because dan Fodio taught Islam to Yunfa.

Dan Fodio fled from Gobir to Gudu and declared a hijra (migration), echoing the Prophet Muhammad’s flight from Mecca to Medina. Fulani clans rallied to his banner. In 1804, he was proclaimed Amir al-Mu’minin (Commander of the Faithful) of what Arabic sources called Dawlat al-Khilāfa fī Bilād al-Sudān—“the Caliphate in the Black Lands.” (The term “Sokoto Caliphate” is a modern shorthand, like “Byzantine Empire.”)

Uthman Dan Fodio and his Mujahedeen (Holy Warriors) declared jihad, launching the most successful Islamic revolution in West African history.

Lightning Conquest (1804-1809)

The jihad gained traction because many Hausa and Fulani saw dan Fodio not as a conqueror but as a purifier. Early campaigns relied on guerrilla tactics and intimate terrain knowledge, exploiting Hausa states weakened by famine and disease.

In October 1808, dan Fodio’s Mujahedeen killed Yunfa. By 1810, Gobir, Zamfara, Kebbi, Zaria, Katsina, and Kano had fallen. Look at the expanded Sokoto map below:

Consolidation and Transformation (1809-1812)

Sokoto became the capital of a new empire stretching across northern Nigeria and into Cameroon and Chad. Despite his earlier purist stance, dan Fodio permitted some regulated cultural practices to stabilize the transition (like allowing music). Former Hausa rulers could return under conditional loyalty oaths; resisters were removed.

By 1812, the old Hausa political order was dismantled. The Fulani-led Caliphate now governed 31 emirates, forming West Africa’s largest centralized Islamic polity.

Dan Fodio ruled from Sokoto as the religious leader until 1815, when he retired from administrative duties. When dan Fodio died in 1817, his son Muhammad Bello became Caliph of Sokoto while his brother Abdullahi ruled the western provinces.

Bello, a skilled administrator, codified sharia governance, expanded schools and libraries, and established the kofa communication system between the Caliphate and emirates.

Governance & Expansion

In terms of governance, many of the reforms that Dan Fodio rallied on were never implemented. For example, arbitrary cattle taxes continued (a tax Dan Fodio said was “non-Sharia compliant”) and enslaving Muslims continued and increased even though Sharia compliance was supposed to be enslaving of pagans.

In terms of expansion, the Caliphate tried moving eastward, but it failed to conquer Bornu, leaving it as Sokoto’s main rival.

But the Caliphate pushed southward raiding and taking more slaves. The Sokoto continued the trans-Saharan slave trade—exporting 3,000–6,000 captives annually to North Africa.

Here’s a zoom in of the territory the Caliphate had:

The Caliphate continued to press on South, swallowing up the Nupe and Igala in the mid 1820s.

Around this time in the 1820s, British explorer Hugh Clapperton became the first European to reach Sokoto, documenting the sophisticated Islamic state. Though he died of tropical disease in a subsequent visit in 1827, his journey highlighted the region's isolation from European influence—a protection that would soon erode with advancements in disease prophylactics.

Then by the late 1830s/early 1840s, the Emirates in the Sokoto Caliphate conquered parts of the Yoruba Oyo empire, specifically Ilorin, a frontier town at the edge of the empire. The Emirates pressed forward and sacked Oyo-Ile and took over other Yoruba towns.

By the mid 1840s, one of the Emirates of Sokoto conquered the Jukun.

Signs of Decline Amidst Conquest (1820s-1845s)

Despite conquering other polities, signs of decline emerged. Many Emirates rebelled. corruption spread, and courts lost credibility. After Bello's death in 1837, each successive Caliph faced succession disputes, emir disobedience, and regional rivalries.

This was a period of a transitional crisis of 1845-1855 saw the older generation of founders dying, creating power vacuums and intensifying succession disputes. Many emirates rebelled, including Katsina and Nupe, while famine struck Kano.

The Unraveling

By the 1850s, Sokoto's centralized grip was loosening. The Caliph's power became largely symbolic as emirs ignored the Caliph’s letters and appointments. Emirates like Hadeija rebelled for over a decade, while Kano experienced a full civil war from 1893-1895 over royal succession.

Without a standing army or centralized military apparatus (Sokoto depended on volunteer village militias), the Caliphate struggled to mount coordinated resistance. The Fulani clerical elite lacked the ability to impose their will on the Hausa once the revolutionary founders died.

Bornu had similar issues, under the leader Umar ibn Muhammad al-Kanemi, he lost most of his tributary states. From 1846 onward, family rivalries, the overuse of delegated authority, and a civil war led to chronic instability.

Bornu was toppled in 1893 by Rabih az-Zubayr, a Sudanese warlord. Rabih ruled briefly before being killed by French forces, after which Bornu’s remnants were gradually absorbed into British-controlled Northern Nigeria.

The collision between the Sokoto Caliphate and European colonial powers was inevitable.

20th Century

Sokoto vs. the British and French

By the late 1890s, the Sokoto Caliphate posed two problems for the British:

Territorial Competition: The Caliph claimed spiritual and political authority over Ilorin, Bida, and Yola—areas already under British protection. This overlap threatened British legitimacy and risked rebellion.

Colonial Rivalry: France, already dominant in West Africa, had designs on Sokoto. In the Berlin Conference in 1885, the Europeans established the “Principle of Effective Occupation”, which meant that to claim territory, a European Power had to physically occupy it not just plant a flag or sign a treaty. British authorities feared being outflanked if France established a protectorate first.

By 1900, the Sokoto Caliphate was still the largest Islamic state in sub-Saharan Africa, with an estimated population of 10 million—about one-quarter of whom were enslaved. Slaves worked plantations. They were sold to Arab-Berbers, used to build infrastructure, and were captured through raids or purchased from surrounding regions. At 1900, Sokoto was the largest slave society on Earth. It’s worth mentioning that slavery in Sokoto differed from the Americas in key ways. In some ways, Sokoto was more brutal since some slaves were forcibly castrated. In many ways, Sokoto was less brutal, since many slaves could own property or become free. Regardless, the fact that Sokoto had slavery was a good imperial excuse for Europeans to come in an “civilize” the Hausa-Fulani.

To assert control, the Royal Niger Company attempted to establish a post and a British Resident in Sokoto in 1899—but the Caliph rebuffed the offer.

British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain now openly advocated war:

The Caliph of Sokoto, Atiku, was unyielding. In a letter to Frederick Lugard, the British military officer of the West African Frontier Force and an employee of the Royal Niger Company, the Caliph wrote:

The caliph’s resistance to British influence convinced Lugard that the only way to secure the Royal Niger protectorate and the rivers of Niger & Benue was the military conquest of Sokoto and its incorporation into the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria. But we discuss colonization in a future substack. Next time, in part IV, we’ll delve into Southern Nigeria, discussing the Benin Kingdom, the Igbo, the Yoruba, and the Trans-Atlantic Slave trade.

Concluding thoughts

Knowing this history makes it interesting to see the similarities and differences between pre and post-colonial Nigeria.

Pre-colonial and post-colonial Nigeria share echoes: elite patronage & corruption and mass discontent. The Sokoto Caliphate rose against perceived unjust rulers—much like today’s insurgent groups (ISWAP & Boko Haram), though with wildly different methods and ideologies.

The Sokoto Caliphate's origins in opposition to corrupt governance continue to resonate in northern Nigerian politics, though contemporary movements like Boko Haram reject the Sokoto Caliphate's emphasis on female education in favor of anti-intellectual extremism.

In addition, the Sokoto Caliphate expanded by preaching and mass support from the peasant class. ISWAP and Boko Haram kidnap, suicide bomb, and kill people indiscriminately.

Ironically, Northern Nigeria was once more literate and cosmopolitan than the South during pre-colonial times. However, after colonialism, due to the North resisting Western education and the South embracing it, the script flipped.

Sources:

Falola, Toyin. A History of Nigeria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Last, Murray. The Sokoto Caliphate. London: Longman, 1967.

Hiribarrren, Vincent, A History of Borno: Trans-Saharan African Empire to Failing Nigerian State. Hurst, 2017

Lovejoy, Paul E. Transformations of Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Reader, John. Africa: A Biography of the Continent. New York: Vintage Books, 1999.

UNESCO. General History of Africa V: Africa from 16th to the 18th Century. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

UNESCO. General History of Africa VI: Africa in the Nineteenth Century until the 1880s. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

UNESCO. General History of Africa VII: Africa Under Colonial Domination 1880-1935. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

Fascinating! Nothing I love more than historical contexts.