Book Review #2: Insights on Javiar Blas' & Jack Farchy's "The World For Sale"

A Much Better Choice Than Confessions of an Economic Hitman

Cynics often intuitively grasp that globalization and international trade have a dark side. They’re aware that powerful multinational corporations exploit developing countries through debt, corruption, and coercion. These aren't always headline stories—many actions are carried out by “shadowy figures” in the West.

For some, Confessions of an Economic Hitman by John Perkins is the go-to book on this subject. However, I have significant & deep criticisms of that book, which I’ll save for another time. Instead, I recommend The World for Sale.

About the Authors

Javier Blas and Jack Farchy are well-regarded journalists and authors, particularly known for their work covering the global commodities markets.

Javier is a Spanish Journalist with a Masters from University of London and has worked as an energy & commodities financial journalist for Financial Times & Bloomberg.

Farchy is a British journalist who studied at University of Oxford who got the Politics, Philosophy, and Economics degree. He also worked at Financial Times and Bloomberg. But he focused more on metals and agriculture, while Javier focused more on oil. Both of them have interviewed commodity traders that I’ll be speaking about.

In 2021, when I was finishing MBA at MIT Sloan, my professor, the Dr. Kristin Forbes, invited a speaker who recommended this book to read. I read this book three years ago, and then it led me on a rabbit hole to learn more about commodity flows.

The book is jammed packed with information. It was written in March 2021, so its fairly recent. Anything I speak after March 2021, are my own insights with the book as my foundation.

In this review I will focus on a couple aspects:

1. Who are these companies?

2. How a trade works?

3. How did commodity trading emerge?

4. The Business Model of Commodity Trading

5. How much money these firms make (My Insights)

6. How Commodity Traders make money (My Insights)

7. Commodity Trading firms that went through bankruptcy or restructuring

8. What’s Wall Street’s Role?

Who are these companies?

If you have never heard of Trafigura, Gunvor, Phibro, Vitol, Marc Rich, and Glencore then perhaps you should read this book.

These commodity traders are quite literally Adam Smith’s “Invisible Hand”. These firms that buy and sell the earth’s resources.

Most of these companies have their headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland (Vitol, Glencore, Gunvor, Mercuria). But there are some non-Swiss firms. Cargill is in Minnesota, and Phibro is headquartered in Stamford, Connecticut. Trafigura and Olam are in Singapore. There are some like Louis Dreyfus in Rotterdam, Netherlands. Most of these firms have big offices in Greenwich, Connecticut, Dubai, Hong Kong, Beijing, and Shanghai as well. For coffee, the Neumann Coffee Group in Hamburg sells your coffee.

These people don’t yell orders on the NY Stock exchange, nor do they sit in front of a computer buying and selling stocks and futures. Rather these are private companies that move bulk orders of commodities from point A to point B.

These firms are privately owned, as in, they are not publicly traded companies that have to do financial disclosure to the NYSE or LSE as mandated by regulators like the American SEC or the British FCA. Out of all of these firms, only Glencore has become recently publicly traded. The rest are private and think of their balance sheet as a trade secret.

How Commodity Trading Works

Back in the 1960s, when Europe could legally buy Iranian oil, a European trader would call Tehran, haggle over prices, and finalize a deal. The Iranian National Oil Company would then send a Telex (before fax & email) confirming the sale, marking the trade.

How did Commodity Trading Emerge?

Commodity trading has roots in antiquity. If you’ve read my articles on Sudan or Mali, then you would know that Egyptians traded grain with the Kerma (modern-day Sudanese) in exchange for slaves, gold & ivory, and the Malians exchanged gold & slaves with the Tuareg Amazigh for salt, which served as a vital food preservative in Medieval West Africa — basically the refrigerator of yesteryear!

Fast forward a few centuries, and one of the most successful commodity trading firms of all time was the British East India Company, founded in the 1600s.

The firm dominated selling cotton, silk, indigo dye, sugar, salt, spices, tea, and slaves back when it was legal. But when Britain banned slavery, the trading of slaves was replaced with a more lucrative cash crop, opium, which devastated China and allowed Britain to take Hong Kong.

Commodity trading started to take its modern form during the Industrial Revolution. British firms like Horseley Ironworks made the steamships in the 1800s. Now for the first time in human history, long distance commodity traders would not die from bad wind in sailboats.

The cost of transporting goods fell dramatically as people could transport tea, spices, metals, grains over long distances. By the mid 1800s, Britain also made commercially viable telegraphs with the British Electric Telegraph Company. Now communication between New York to London happened in minutes instead of weeks.

By the late 1800s, Germany led metals trading, while America, through Cargill, dominated wheat. Many German traders relocated to London where financing is easier. After WW2, oil became a globally traded commodity with an international price for the first time.

Initially these commodity traders operated like adventurers, they evaded trade embargoes & sanctions and made a mockery of laws, like dodging Iranian sanctions. These people spend years on the “I-hate-you-list” of the U.S. Justice System. If you want names, in the 1960s & 1970s, the dominate player was the Phillips Brothers led by Ludwig Jesselson. In the 1980s, it was Glencore.

Other big commodity traders were people like Marc Rich & Pincus Green, who were pardoned by Bill Clinton.

Rich and Green created the model of paying their vetted loyal staff, handsomely well, where morality plays no consideration to their trades.

The Business Model

Their business model is quite simple - commodity traders are price exploiters. They buy natural resources in one time and place, and sell them to another to make a profit. This role exists because the supply and demand of commodities don’t match. Most mines, farms, and oil fields aren’t located where the buyers of these goods are. The former is located places in like Australia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Brazil, and Saudi Arabia, while the latter is located in Britain, Japan, and Switzerland.

In addition, not every Argentinian soybean farmer or Zambian copper miner has a network of offices around the world to sell their products to. In addition, most commodity markets are either over and under supplied. That’s where the value-add of commodity traders come in, ready to take a commodity off a producer’s hand at the right price, or provide it to a consumer if they are wiling to pay. They are highly levered, and they buy commodities using loans from banks. What’s interesting is that they aren’t really borrowing from Wall Street Banks, but they usually borrow from European commercial banks like BNP Paribas (before BNP stopped due to corruption scandals), Société General, ING, Credit Suisse, or UniCredit of Italy.

The Revenues & Profits of Major Commodity Traders

Revenue wise these firms make hundreds of billions like a top American tech firm, but net income wise, they have more costs. See graph below:

Cargill made $177B in revenue in 2023. It’s net income (so subtract cost of goods sold, wages, operating expenses, capital expenditure, interest expense on debt) is $3.81B, roughly a 2% income margin.

Vitol’s revenue was $400B in 2023, with a net income of $13B, 3% income margin.

Trafigura’s revenue was $244B in 2023, with a net income of $7.4B, a 3% income margin.

Glencore’s revenue was $218B in 2023, with a net income of $4.18B, a 2% income margin.

It’s worth noting that Glencore is the only publicly traded company among them, listed on the London Stock Exchange, and is required to report accurate financial information to shareholders. In contrast, Vitol, Cargill, and Trafigura are private, so their financial disclosures are limited to what they report to outlets like Reuters or Bloomberg. However, their revenue and profit margins are comparable, suggesting the figures are somewhat reliable. This makes sense considering they all have to deal with logistics, financing, staff, purchasing, insurance, and transportation costs, but obviously there is still shady accounting occurring.

For context, these firms generate revenue similar to Google (2023 Revenue: $306B). However, Google has a much higher income margin. In 2023, Google had a net income of $74B, a 24% income margin.

Are Commodity Traders Necessary? Unveiling the Corruption Behind the Industry

Commodity traders are essential; without them, we wouldn’t have fuel for our cars, tea in our cups, or flour for our bakeries. However, their operations are often shrouded in secrecy and corruption.

For many years, Switzerland had no anti-corruption laws to prohibit the bribing of government officials. Remarkably, in Switzerland, bribes were tax deductible. They euphemistically called “facilitation fees”, and were considered to be the cost of paying for access. In America, under Jimmy Carter, America finally introduced anti-bribery laws by the late 1970s. But there’s no regulator to report these trades to. Commodity traders are not obligated under any purview to disclose any of their trades.

The lack of regulation is due in part to the global nature of physical trading, which often places it beyond the reach of national jurisdictions. Most politicians, particularly in the United States, remain unaware of the scale and influence of these firms. While American banks are subject to scrutiny by entities like the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), pure-play commodity traders operate with almost no oversight. There is no international body, no UN agency, and no World Trade Organization mandate that regulates this sector or monitors their trades.

In 1979, the G7 tried to make an international repository of oil physical deals, and that hasn’t happened due to opposition from the commodity traders. The industry’s resistance to transparency continues to allow questionable practices to flourish, shielded from the public eye.

How a Trade works

A typical shady trade right now probably involves Russian/Iranian oil since they are under sanctions. The firm usually has a subsidiary in a tax haven like Cyprus or British Virgin Islands. In this example, the firm buys 1M barrels of oil from Russian Rosneft. At ~$80 per barrel, that costs the firm $80M.

The trader likely puts down just $4 million of their own money, a mere 5%, and turns to Société Générale to borrow the remaining $76 million, leveraging the deal at 95%.

To finance this, the trader typically has two options: revolving credit, which allows them to borrow, repay, and reborrow within a set limit, or a bilateral deal, where they secure private financing directly from the seller and repay the loan later.

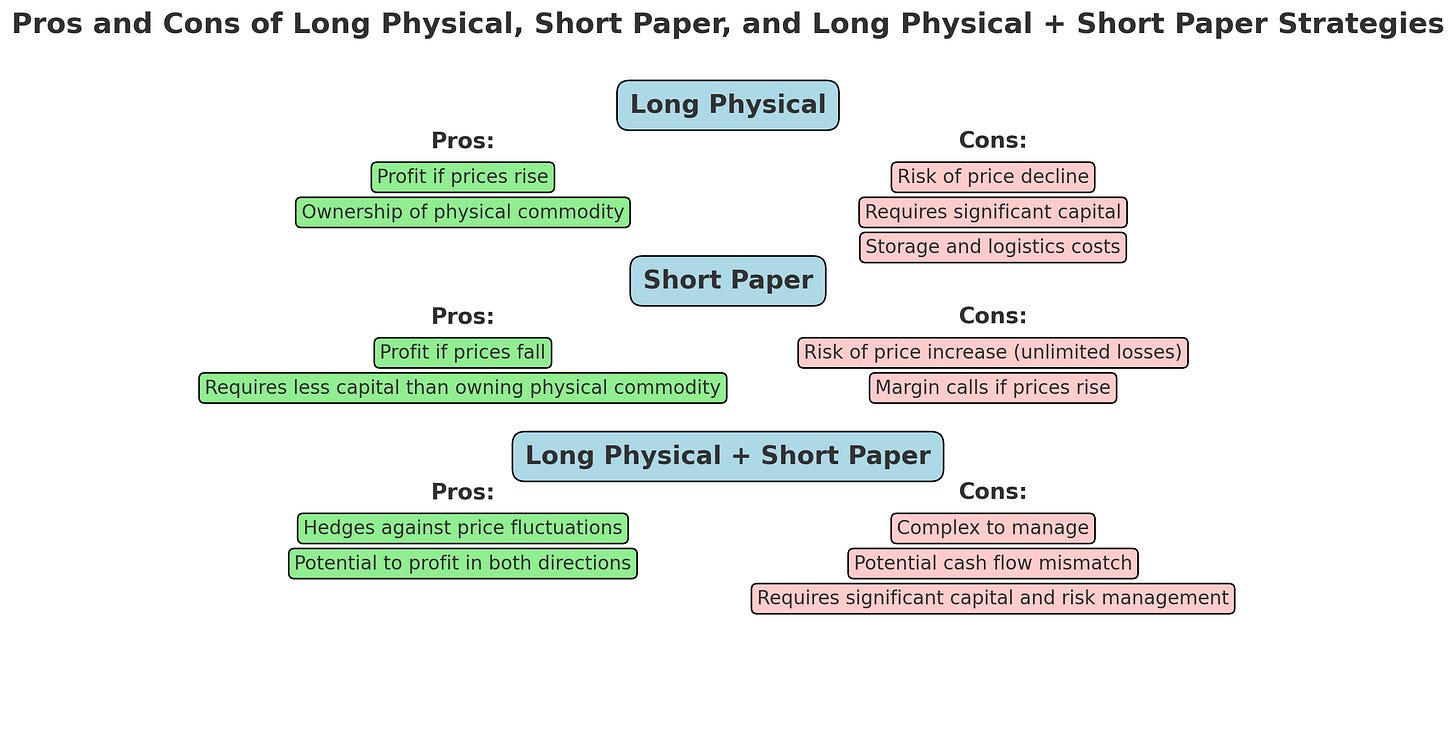

Strategies in Play

There are different positions you can make in an oil trade. I’ll just explain a few:

1. “Long Physical”

2. “Short Paper”

3. “Long Physical, Short Paper”

“Long Physical”

By purchasing the 1 million barrels, the trader now owns the oil, or is "long physical." They profit if oil prices rise but risk losses if prices fall. So, they hold onto the oil, waiting for the market to move in their favor before selling.

“Short Paper”

Let’s say you want to make money when the price of oil drops.

So what the trader does is take a short position on a futures market contract, commonly referred to as “short paper”. For those unfamiliar with short selling, the trader sells a futures contract with the underlying expectation that the price of oil will decrease. In this example, the trader sells a futures contract for 1M barrels at $80 per barrel ($80M earned). Selling a futures contract creates an obligation — the trader must deliver physical oil or settle the contract before the contract’s expiration date. If oil prices drop to $70 per barrel before the specified date, as the trader predicted, the trader can “close” the short position by buying back a similar futures contract for $70M. You pocket the difference ($80M - $70M = $10M).

Buying back a futures contract after selling one effectively cancels out the initial obligation, ending the trade. (It’s like borrowing your friend’s Toyota for a month, with the promise that you’ll return it. On the first day, you sell your friend’s Toyota for $30K, expecting that the value of similar cars will drop. As the month progresses, the price of used Toyotas indeed drops, and you find another one for $20K. You buy it and give it back to your friend, fulfilling your promise. After returning the car, you’ve made a $10K profit because you sold it high and bought it back low).

However, if oil prices rise to $90, you'll start losing money. This situation triggers what's known as a margin call, where traders say you are "underwater." The firm betted on prices going down, but they went up, and now the firm must cover their losses.

Your broker will require you to deposit more funds (a margin call) to cover the increased value of the contract. Initially, you received $80 million from selling the contract. Now, with prices at $90 per barrel, the contract's value has increased to $90 million. To close your position, you need to buy it back for $90 million, which means you would need to deposit an additional $10 million to cover the difference. This deposit ensures that you can fulfill your obligation and close the contract.

Long Physical, Short Paper.

You physically buy $80 per barrel, hoping prices will rise (long physical). But to protect yourself in case prices drop below $80, you hedge by also taking a short position by selling a futures contract (short paper). This strategy should allow you to make money no matter where prices go.

But then, complications arise. Suppose oil prices do climb to $90 per barrel, but your shipment hasn’t arrived yet to the customer. Now you’re in a bind with a cash flow mismatch: you haven’t sold the physical oil to your client yet (it takes 2 to 14 days to ship depending on location/transportation mode), so your cash from the long position is still tied up. Meanwhile, because oil prices are rising, your short position is losing money fast, and your broker hits you with a margin call, demanding more funds immediately.

To put it simply, if you long physical, short papers and oil prices are rising, making money from physically selling oil takes days/weeks, while losing money on your margin call is literally an instant phone call away from your broker.

If you are getting margin calls, you need to borrow from another bank to cover the margin call. If you’re managing multiple tankers, the problem magnifies— hundreds of millions or even billions dollars could be at risk. Eventually, if you are so underwater, one bank will just stop lending to you.

Here’s a diagram summarizing what I said:

This exact scenario played out in early 2022, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Many traders were caught with short positions that sank underwater as oil prices spiked. Desperate, the European Federation of Energy Traders, a lobbying group for commodity trading firms, pleaded with the European Central Bank (ECB) for emergency funding to stay afloat.

On April 1st, 2022, the ECB refused, and it wasn’t an April Fools’ joke. The Bank of England also declined to intervene, citing the “opacity” in the market.

If a central bank lent to a commodity trader and it failed, then a bunch of billions of loans to many European banks would have billions lost of exposure, and then some European banks would be under stress. In addition, many of these firms aren’t even incorporated in Europe, you would be bailing out banks in the British Virgin Islands, Dubai, or Singapore.

Also even if they are European, imagine the outrage if the ECB had bailed out a Cyprus-based trader dealing in Russian oil.

The ECB and Federal Reserve made it clear: the threshold for bailing out an unregulated market like this is incredibly high. They suggested that commodity traders should raise equity instead.

In such volatile times, even the biggest commodity traders struggle to hedge effectively. When the market turns against them, the consequences can be catastrophic.

Commodity Trading Firms that Went Bankrupt or Went Through Restructuring

This brings me to my next point. Many of these firms have gone bankrupt at worse or restructuring at best.

Enron (2001), Refco (2005), SemGroup (2008), MF Global (2011),Noble Group (2018), and more.

Why don’t Banks do this?

Many banks do and used to do more.

Goldman has J. Aron & Co that sells commodities. JP Morgan has a commodity arm, Morgan Stanley, Citi, Bank of America, Barclays, Deutsche Bank, and other banks have commodity trading divisions as well.

Over time, commodity trading shifted to firms that aren’t listed on exchanges (like your local deli), where the real money is made by navigating the murky waters of corruption and developing nations. Publicly traded banks, under the watchful eyes of regulators, couldn’t afford to engage in such risky deals without facing hefty fines. But for non publicly traded firms, the biggest profits come from operating in the gray areas—places where legality and ethics blur.

What do these gray areas look like?

Bypassing sanctions to help Saddam Hussein sell oil after failing to annex Kuwait

Skirting international law to supply oil to Apartheid South Africa.

Fueling conflicts by providing Libyan rebels with the resources to overthrow Gaddafi.

Defying embargos by trading sugar for oil with Fidel Castro’s Cuba.

Creating Russian oligarchs during the chaotic privatization of Russian state owned enterprises after the Soviet Union’s collapse.

Striking corrupt deals with Joseph Kabila, the former president of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

If you’re intrigued by these shadowy dealings, you should definitely pick up the book for the full story!

While JP Morgan avoids massive oil trading with Putin due to the enormous fines and scrutiny, firms like Trafigura are more than willing to step into that gray area, trading Russian oil without hesitation.

Book Score:

If you're looking for an eye-opening introduction to commodity trading and the darker side of globalization, Javier’s and Jack’s The World for Sale is the best book I can recommend. If you have a Bloomberg subscription, their posts there are also worth your time.

For those with a cynical outlook on capitalism, this book far surpasses Confessions of an Economic Hitman. While Economic Hitman indulges in conspiratorial thinking, false causality, and outright errors, The World for Sale offers well-researched, grounded insights. But reviewing Economic Hitman is a topic for another day.

Previously, I reviewed Dambisa Moyo’s Dead Aid and rated it an 8.6 out of 10.

The World for Sale? A 9.5 out of 10.

Outside of oil, gas and gold are "corrupt" deals with authoritarian governments even worthwhile anymore from a purely financial perspective? If I'm not mistaken most major commodities prices have fallen since the 90s. I guess that also means that becoming a high income country through commodities (like Argentina in the early 20th century or the Gulf monarchies and Botswana today) will become less likely.