The Economic & Geopolitical History of Uganda Part II: Obote vs The Bugandan King and Amin vs Tanzania & Israel

Kingdoms, Crises, & Coups: Uganda’s Tumultuous Post-Independence Journey

Last time, we discussed Uganda’s traditional history. There were many kingdoms - Buganda, Toro, Bunyoro, and more. Around the 1800s, Egyptians and their Sudanese vassals started enslaving people from Bunyoro, while Zanzibari Arabs started trading for slaves with Buganda. By the late 1800s, the British came in, ended the slave trade, and formed an alliance with Bugandans to conquer the other kingdoms, creating Uganda, a mispronunciation of Buganda. Britain brought South Asians and favored the Bugandans in the protectorate. Post WW2, after many riots and internal issues, Uganda gained independence in 1962 with Milton Obote, a northerner Lango-ethnic as Prime Minister & the Buganda King, Mutesa II as President.

Independence & Milton Obote (1962-1971)

Imagine leading a newly independent country where most of the African population are subsistence farmers, South Asians dominate the civil service and manufacturing, and Europeans control much of the service industry. What path would you take to unite such a fragmented society?

Uganda, at the time of its independence, was not a cohesive nation but a patchwork of deeply entrenched tribal loyalties. The most prominent of these was the Buganda Kingdom, which had managed to retain a degree of autonomy during British colonial rule. British rule in Uganda lasted around 70 years— thus Ugandans still had generational memory of their pre-colonial structures and loyalties.

Uganda’s federal constitution reflected this tribal reality. Kingdoms like Buganda were given substantial autonomy, fostering division rather than unity.

Obote’s Rise and the Struggle for Unity

Milton Obote, Uganda’s first Prime Minister, hailed from the Lango region in the North. He built his base of support among his fellow Northerners, particularly in Langi and Acholi, but other regional political bosses catered to their own tribal interests. Being Prime Minister was more like becoming patronage broker who traded development projects to local/regional interest groups in return for political loyalty.

Obote quickly grew frustrated with the limitations of a multiparty democracy in such a fragmented society. He believed that to build a strong, centralized government, tribal patronage networks had to be dismantled. The UPC, Obote’s party, initially allied with Buganda’s monarchist party, but their goals were diametrically opposed: the UPC sought a unified, socialist Uganda, while Buganda wanted autonomy and influence over other kingdoms.

Geopolitical Maneuvers and Early Conflicts (China, Israel, Britain, & Congo)

Internationally, Uganda, under Obote, was one of the first nations to acknowledge Peking/Beijing as true China instead of Taipei.

Obote also forged a close relationship with Israel, receiving military and agricultural assistance as part of Israel's broader Periphery Doctrine, which aimed to counter Arab hostility by building alliances in East Africa. This relationship saw Uganda become a conduit for weapons to Southern Sudanese rebels (the Anya Nya), supported by Israel in their fight against the Arab-dominated Sudanese government. Fun fact, British Uganda was one of the candidate regions for a Jewish State among the early Zionists.

UK & Domestic Issues:

Domestically, tensions flared between Uganda’s tribes. In 1964, the Bunyoro people demanded the return of their "lost counties" from Buganda, leading to riots. Obote used his military to quell the unrest but decided to return the counties to Bunyoro, further alienating Buganda.

The same year, discontent within the military boiled over into a mutiny over pay and the dominance of British officers. To resolve this, Obote asked the British to put down the mutiny, and then Obote “Africanized” the military, promoting officers from his own tribe and other Northerners. Among these Northerners was Idi Amin, an uneducated but ambitious soldier who quickly rose through the ranks, becoming close to Obote. Amin laid the groundwork for the military to become a central player in Ugandan politics. When another rebellion occurred in Jinja, Uganda’s second largest city, Idi Amin put down the rebellion.

Congo Crisis and Corruption

Obote was depressed that Lumumba was killed and that the American CIA supported Joseph Kasa-Vubu and Mobutu. As the Congo Crisis unfolded, Obote and Amin saw an opportunity for personal enrichment and a chance to help the Chinese & Soviet backed Antoine Gizenga government, who wanted to avenge Lumumba (see Red borders).

In 1966, Amin and his army were supporting the Gisenga government in a barter deal. The Soviet-backed, Gizenga government would give Amin and his army gold and ivory, and Amin would provide Gisenga weapons procured from China. This was revealed when Gisenga’s government said that Amin failed to provide them some of the arms they requested. Also, when Amin went to the bank to exchange the gold for over $200K, the gold bar had a Congolese stamp on it.

Obote’s involvement in this corruption sparked outrage. President Edward Mutesa II, the Buganda King and ceremonial head of state, called for an investigation. Facing removal by parliament, Obote acted swiftly—ordering Amin to stage a coup to secure his grip on power.

The Coup and Consolidation of Power

In 1966, Obote suspended the constitution and abolished the federal system that had granted autonomy to the kingdoms. This made Buganda's King Mutesa II declare Bugandan independence, but Obote sent Amin and the military to storm the royal palace. Here’s a video of a Buganda Palace Crisis (Mengo Crisis):

Hundreds died, and the King fled to Britain. Obote then declared himself President and dissolved the centuries-old kingdoms of Buganda, Ankole, Bunyoro, Toro, and Busoga.

To cement his rule, Obote imposed martial law and created a secret police force, the General Service Department, led by his cousin and composed mainly of Langi tribesmen. They were trained by the Israeli Mossad and British MI6. The army & police were reshuffled, with pro-Obote troops from the north replacing soldiers from rival regions.

Pan African, Socialist Economic Policies and Growing Paranoia

Obote signed the East African Common Services Organization (EASCO) agreement with Tanzania and Kenya in 1961. The agreement was very weak, but it allowed collaboration on scientific research and university education. That agreement dissolved and they tried again with the East African Community (EAC) in 1967.

Obote pursued socialist economic policies, issuing the “Common Man’s Charter,” which echoed similar ideas from neighboring Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere. The government nationalized industries, buying out or owning shares in colonial-era enterprises, South Asian firms, and establishing state ownership in key sectors like manufacturing and agriculture. Infrastructure projects followed, with investments in schools, railways, and healthcare.

In terms of manufacturing, he protected state owned industries from foreign competition with a wall of tariffs and subsidized them with government revenue until they can compete with foreign competition on their own. The manufacturing that Obote was “betting” on was food processing, sugar milling, beverages, footwear, paper, chemicals, steel, textiles, & other consumer & industrial goods. Unfortunately, Uganda has been remarkably unsuccessful. Uganda still doesn’t sell even $1B in any of these categories.

The economy was actually growing fast, though bolstered by high coffee and cotton prices. Obote also tried diversifying to tobacco & tea, but sometimes bad harvest seasons got in the way. However, Uganda’s economic growth could not keep pace with Uganda’s rapidly growing population due to his healthcare improvements. The demographic transition—the population explosion from high birth and high death rates to high birth and low death rates—put immense pressure on resources, leading to food shortages and soaring prices. Milton’s government ministers also siphoned funds from the government owned firms. The marketing board for coffee and cotton also siphoned wages from the farmers by paying them low wages so the board could be more profitable.

Obote’s troubles were compounded by his growing paranoia. In 1969, Bugandan dissidents attempted to assassinate him with a grenade, but he narrowly escaped. His fears of growing opposition led him to rely even more on ethnic favoritism, promoting Langi and Acholi soldiers and creating paramilitary forces loyal to him. Meanwhile, Amin continued building his own power base, largely composed of soldiers from his Kakwa tribe in West Nile.

The Fall of Obote

Obote’s relationship with Israel soured after the Six-Day War in 1967, as Uganda and other African nations condemned Israel’s occupation of the Sinai Peninsula, Golan Heights, Shebaa Farms, Gaza, West Bank/Judea & Samaria, and East Jerusalem/Al-Quds.

Obote shifted his support to Arabs and Sudan’s Arab Nationalist, Gaafar al-Nimeiry, cutting ties with the Anya Nya rebels. However, Amin, with personal ties to the Kakwa people of South Sudan, continued to secretly support the rebels, embezzling army funds to supply them.

As tensions between Obote and Amin escalated, Obote attempted to sideline Amin by demoting him. But Amin had already secured backing from Israel and Britain. In 1971, while Obote was attending a Commonwealth conference in Singapore, Amin seized the opportunity and launched a coup. Obote fled to Tanzania, where President Julius Nyerere, a fellow socialist, granted him asylum and a stipend.

Around the time of Obote’s ousting, thousands of Tutsi Burundis & Rwandans fled to Uganda to escape persecution, Uganda’s economy was in shambles, and the country had taken its first loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) due to being bankrupt.

Idi Amin (1971-1979)

Rise to Power

Idi Amin, remembered in the West as an idiotic, Anti-Semitic dictator, came to power in Uganda after deposing Milton Obote in 1971. Amin, a member of the Kakwa tribe and Muslim minority in the West Nile region, was initially a popular figure for overthrowing Obote. He freed political prisoners, and allowed the body of the exiled Bugandan King to be returned to Uganda for burial.

His appeal was particularly strong among Uganda’s Muslim minority, as he redistributed land confiscated from South Asians to the Uganda Muslim Supreme Council. Amin tried converting the population to Islam, but that failed miserably.

He replaced Obote’s Acholi & Langi favoritism with Kakwa favoritism in government.

However, some African leaders like Nyerere of Tanzania & Kaunda of Zambia hated Amin. Nixon closed his embassy in Uganda and Britain did so in 1976. Kenyatta of Kenya also wasn’t a fan since Amin wanted parts of Kenya. Amin’s poor relations with Kenya & Tanzania destroyed the East African Community in 1977.

Amin’s “Economic War”

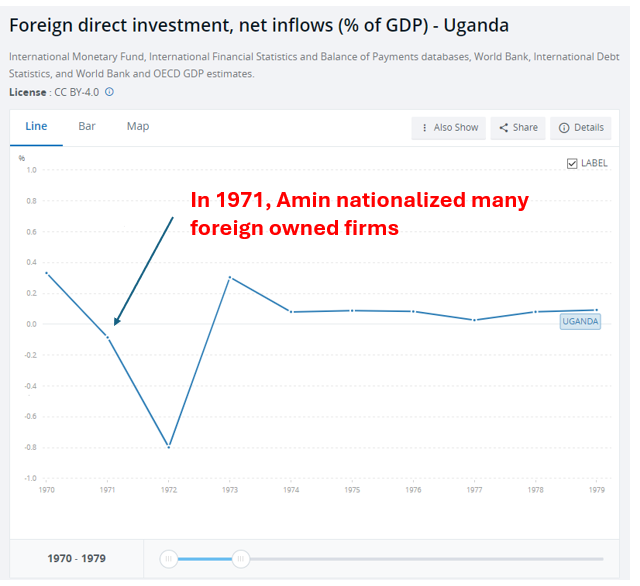

Amin had a very myopic view of foreign investment. He thought foreign ownership of firms meant “neocolonialism”. So he declared “economic war” by nationalizing foreign owned firms. In 1972 and 1973, many firms pulled out, resulting in negative foreign direct investment (FDI). After 1974, foreign investment as a % of economic output never recovered to Obote levels, averaging out to a meager amount of 0.1% of GDP. It didn’t help that in 1975, Amin expropriated more foreign firms, like all 85 British owned businesses that operated in Uganda.

Kicking out productive minorities: In 1972 Idi Amin, on a hunch, decided to kick out 50K South Asians. (See his “justification” here).

This led to a refugee crisis where thousands of South Asian Ugandans had to flee to Britain, India or Pakistan. This was arguably a numb-skull move, since this obliterated the commercial, financial, agricultural, and skilled artisan sectors of Uganda’s economy. Idi gave these jobs mainly to government nominees of his Kakwa tribe from the West Nile region, the Sudanese Muslim minority, and the military.

Very few of Amin’s loyalists knew how to run a business. The once profitable South Asian shops were run to the ground. Expelling the Indian minority brought a decimation to manufacturing and farming in Uganda. Ugandan bread, salt, and milk production declined and Ugandans had to import these goods from abroad. Ugandans had to go through a black market system to import goods, known as “Magendo”. Amin’s military officers that took over the South Asian shops were known as “Maufta Mingi”, meaning a lot of fat/wealth/oil. Regardless, as sad as it was, kicking out South Asians fomented a sense of nationalism amongst Ugandans. Amin told the banks to keep lending to keep these firms afloat. In addition, Amin borrowed in foreign currency to ensure these unproductive, unprofitable firms survived.

Brutality

Amin also established a reign of terror. He formed killer squads composed of the military police, Presidential Guard, Public Safety unit, and Bureau of State research, targeting political opponents, particularly the Acholi and Langi tribes loyal to Obote. These squads were responsible for mass killings, including the deaths of government officials, the chief justice, and even an archbishop. Ethnic massacres continued throughout his rule, and estimates of the death toll range from 80,000 to 500,000. While not every death was directly under Amin’s control, his regime fostered a climate of fear and violence. His Nile Mansions Hotel had a dungeon filled with civil servants, playwrights, and “spies”.

Shift in Foreign Policy

Initially, Amin maintained good relations with Israel, since Israel helped with his coup and provided loans and economic aid. However, things changed. To discuss why, we need to talk about Tanzania first.

Uganda, Tanzania, & Israel

Ever since Obote was granted asylum, Obote & Nyerere backed Ugandan rebel groups to overthrow Amin.

In 1972, a militia of 1000 Obote supporters that were exiled to Tanzania tried to remove Amin but failed. Amin then claimed that Nyerere of Tanzania wanted to destabilize Uganda, under Obote’s orders.

Then Amin claimed that the Kagera Salient, a Tanzanian region that borders Uganda, should be part of Uganda since it was briefly part of Uganda during colonial rule.

Amin wanted to bomb border towns in Tanzania, but Israel refused to provide Amin arms. This made Amin hate Israel, so Amin closed the Israeli embassy in Uganda and started supporting the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). He also turned to Muammar Gaddafi of Libya for arms. Gaddafi & Arafat of the PLO both befriended Amin, while Jordan, Iraq, and Syria disliked Amin.

Gaddafi built Mosques in Uganda for free as appreciation and provided him security experts who saved him from assassination attempts.

Yasser Arafat became so close with Amin, that he was Amin’s best man at Amin’s wedding in the 1970s.

With Gaddafi’s arms, Amin bombed northern Tanzanian towns of Mwanza and Bukoba near the border. Uganda then invaded but their force was defeated. Nyerere did not want war with Amin so in October 1972, the two leaders signed a peace agreement in Mogadishu. The agreement said they would withdraw troops from their border towns, but they still hated each other.

Amin & Israel

Amin started to hate Israel and Jews. He said he was going to erect a monument of Adolf Hitler. In addition, he said the following:

He also praised the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre of Israelis.

In 1976, an Air France flight en route from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and diverted to Uganda's Entebbe Airport, with the approval of Ugandan President Idi Amin. The hijackers held Israeli hostages and demanded the release of 53 militants imprisoned in various countries, including Israel, West Germany, and Kenya.

In response, Israel’s Mossad and Britain’s MI6 orchestrated a daring commando raid, known as Operation Entebbe, to rescue the hostages. Most of the hostages were freed, but one Israeli woman, Dora Bloch, was executed by Ugandan forces.

Meanwhile, another rebel group that wanted to remove Amin emerged, led by future President Museveni, called FRONASA.

Uganda-Tanzania War (1978-1979)

By 1978, Idi Amin had become increasingly paranoid, especially after the Palestinians and Libyans saved his regime from multiple assassination attempts linked to Obote. His paranoia reached a peak when he ordered the killing of an archbishop for allegedly accusing him of being an Obote spy.

International backlash grew after Amin’s actions, prompting Jimmy Carter to ban American firms from buying Ugandan coffee beans. These sanctions ban had little effect on America since America makes its own beans and buys from Mexico, Ethiopia, & Brazil, but this crippled Uganda’s economy since 97% of Uganda’s foreign exchange to buy food & fuel came from coffee exports to countries like America. Already suffering from a global slump in coffee prices, this led to the collapse of Amin's patronage network, which depended on foreign earnings to secure military loyalty.

Invaded Tanzania: In a desperate attempt to distract the military and save his regime, Amin invaded Tanzania's Kagera Salient in 1978 with the backing of Gaddafi's troops, looting and bombing villages. He was internationally condemned and withdrew. However, in January 1979, Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere retaliated, joining forces with Ugandan rebel militias led by former president Milton Obote and Yoweri Museveni.

The Palestinian Liberation Organization, Sudanese from Al-Nimeiri, and Muammar Gaddafi of Libya provided arms & soldiers for Uganda, but Nyerere and the rebels captured Kampala and Amin fled to Gaddafi’s Libya, then Saudi Arabia.

The war devastated Uganda, with the collapse of cotton, tea, and tobacco production, widespread looting, and a return of diseases like cholera.

The Chaotic Transitional Period (1979-1980)

After Amin fled Uganda in 1979, the country entered a turbulent transitional phase. Several short-lived leaders struggled to stabilize Uganda, which had been devastated by Amin's dictatorship.

First, Yusuf Lule was appointed president in April 1979 by the National Liberation Front (UNLF). He was Bugandan and had the Kingdom’s support, but he had very little room to maneuver - real political power lied in the UPC activist Paulo Muwanga who was trying to resurrect Obote’s career, the rebel leader Yoweri Museveni, and Julius Nyerere of Tanzania who now had significant sway over power in Uganda.

Lule tried to centralize power & reform the army, which led to riots and alienated key political factions, leading to his removal after two months in power.

Next, Godfrey Binaisa took over in June 1979. A former attorney general under Obote who made the constitution abolishing traditional Kingdoms, which made him hated by other Buganda. Binaisa tried to reform the military and police and stabilize the economy. But when he attempted to reshuffle top military leadership, he faced resistance. In May 1980, Binaisa was ousted in a coup by Paulo Muwanga.

Muwanga, backed by rebel leaders like Yoweri Museveni, ruled Uganda for the rest of 1980. His main task was to organize national elections. He violently intimidated the opposition parties like DP. He also sent soldiers and militia to kill Acholi activists and opposition supporters. The December 1980 elections were widely regarded as rigged in favor of Obote’s return.

Concluding Thoughts

We have gone full circle! Obote the founding father was ousted by Amin. Then after Amin’s mayhem, Obote returned.

Unfortunately, Obote returned to rule a state poorer than it was at independence. Read Part III here and look at the graph below:

Assad's Syria and Saddam Hussein's Irak were built on 'cooperating' minorities against a majority, where the loyalty of the minorities to the leader was guaranteed by real threats of suppression or extinction from the majority. Those were religious rather than tribal antagonisms, but effective in its cruelty until it was not. Gaddafi was maybe special in his balancing of different groups; will you tell that story some time?

Love learning about post-colonial African history. Keep it up.