The Economic & Geopolitical History of Uganda, Part III: The Obote-Museveni Conflict, Museveni’s Reforms, and Museveni's Regional Influence in Rwanda & Congo!

From Obote to Museveni: Uganda’s Path through Conflict and Transformation

Read Part I for Uganda's pre-colonial and colonial history and Part II for Milton Obote, Idi Amin, and the transitional period. Elections were held during the transition period, and Milton Obote was re-elected. However, many Ugandans believed the election was rigged.

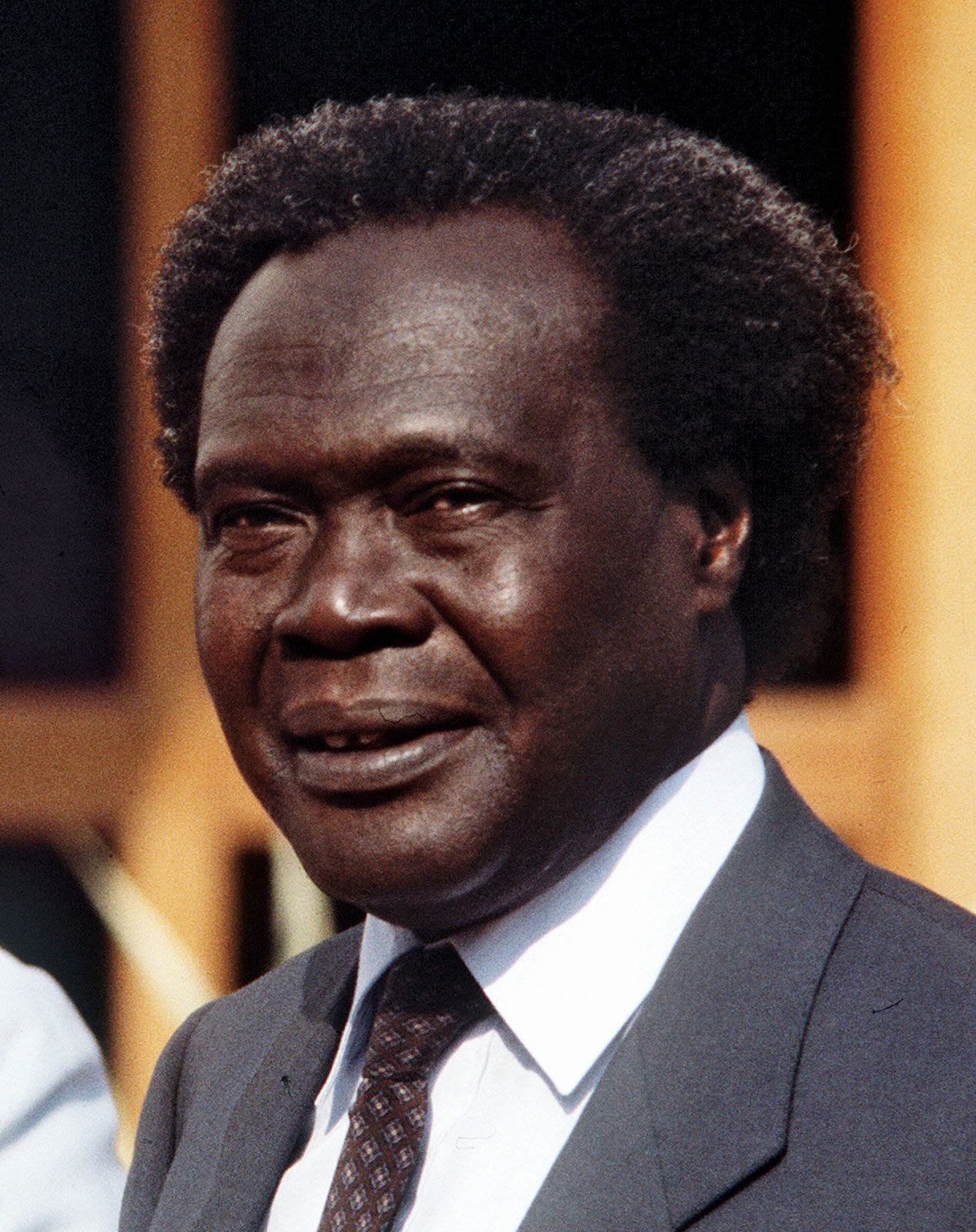

Milton Obote (1980-1985)

Obote’s Power Issues:

Widespread suspicions of election rigging, fueled by voter intimidation in anti-Obote strongholds in Buganda and Southwest Uganda, led many Ugandans to view Obote as illegitimate. Yusuf Lule, a former transitional leader, and Yoweri Museveni, a candidate in the election, founded the National Resistance Movement (NRM) to launch an armed rebellion. Alongside other rebel groups and exiled Rwandan Tutsi Refugees in Uganda like Paul Kagame, Museveni launched an attack on a Ugandan military academy to grab weapons and attack Obote’s forces, igniting the Ugandan Bush War (1981-1986).

Due to the low-trust nature of Ugandan society, President Obote used his Northerner army to brutally suppress dissent, relying on Langi (Obote’s tribe) and Acholi officers to control the military and government, further isolating the Buganda and other southern groups.

The Ugandan “Marshall Plan” 1.0

Uganda’s economy was in ruins after Idi Amin’s mismanagement and his costly war with Tanzania. 97% of Uganda’s export earnings came from exporting coffee beans, but deteriorating infrastructure and farm land made it difficult to export cash crops. In Obote’s first term, he was an ardent socialist who believed in state owned enterprises. But after seeing the abject failure of socialism in Tanzania when he was in exile, he was more flexible with some aspects of capitalism.

With no foreign reserves remaining and minimal investment interest from foreigners, Obote negotiated with the IMF for a structural adjustment program borrowing 302M SDR (~$338M) and $750M in Western aid.

1. Devaluing currency to harmonize official and black market exchange rates

2. Cutting government spending and reducing food subsidies to show fiscal responsibility in order to receive more cheap loans from international lenders.

3. Changing foreign investment laws to attract foreign capital and encourage South Asians exiled by Amin to return.

4. Raising prices paid to coffee farmers by the state marketing board. This action reduced the desire for Ugandan farmers to illegally sell coffee beans in Kenya, where they historically paid more.

However, war hindered these reforms. Foreign investment was non-existent since businesses don’t like to invest in a place where their assets could be blown up. Unemployment and inflation were still sky high. In addition, Obote’s refusal to hold another election further weakened his legitimacy.

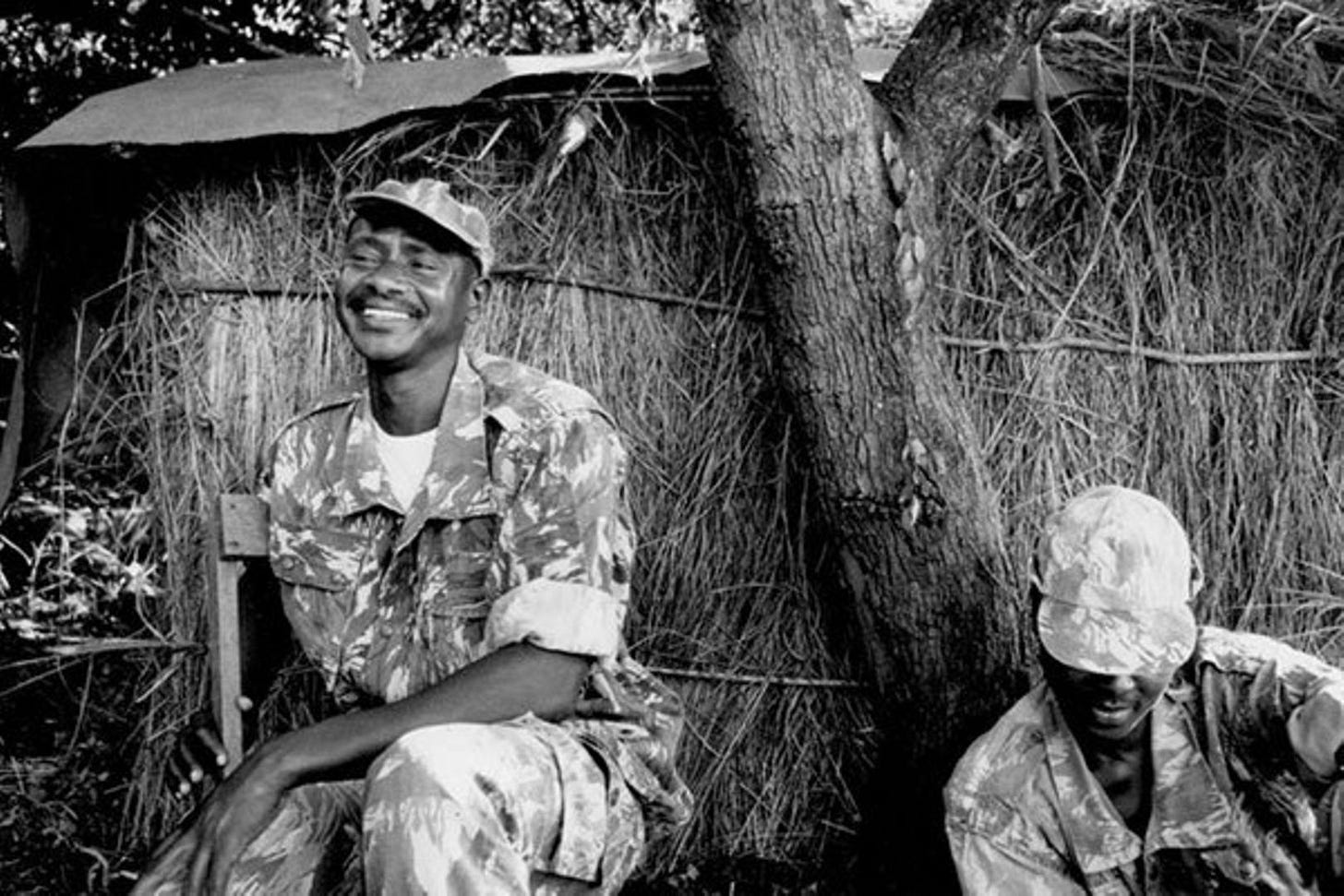

The Uganda Bush War (1980—1986)

Armed by Gaddafi of Libya, Museveni’s National Resistance Army (NRA) launched guerilla warfare targeting Obote loyalists and military installations through ambushes, sabotage, and hit-and-run attacks. At the same time, Museveni provided social services to his peasant base in the South, destabilizing Obote’s regime while building support for his future rule.

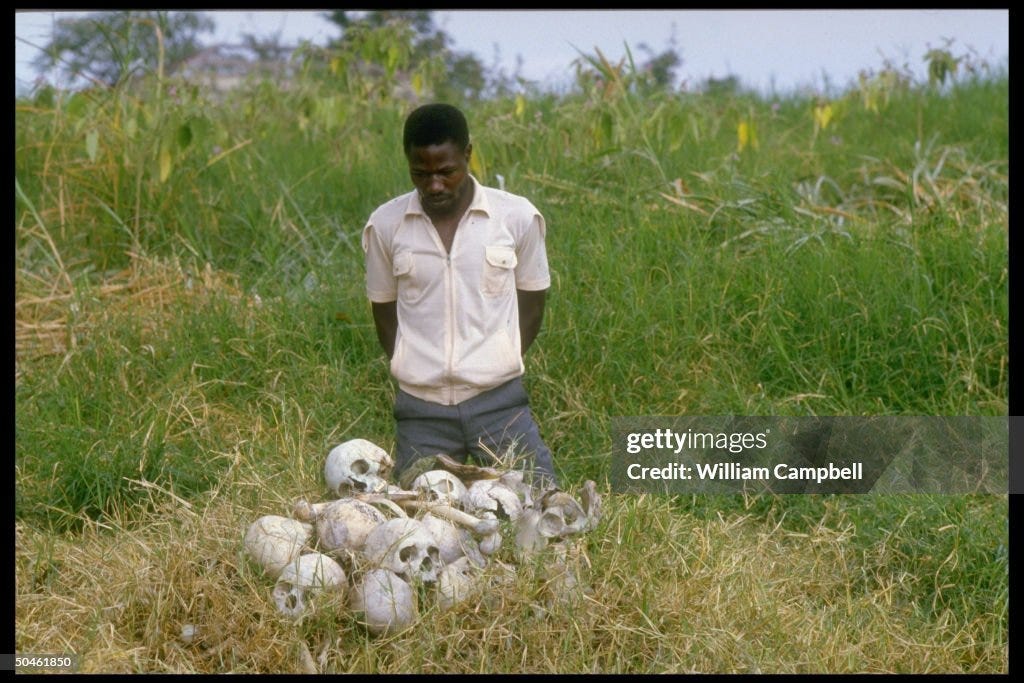

In response, Obote, backed by Canada, Australia, the UK, and even North Korea, used brutal, arguably genocidal, scorched-earth tactics, targeting civilians in the Luwero Triangle—Buganda’s heartland & Museveni’s base—with mass indiscriminate killings, starvation, forced displacements, child abductions, and mass graves. This violence led thousands to flee to Southern Sudan, itself in conflict. The devastation of Buganda, once prosperous, led international supporters like Canada, the IMF, and Australia to abandon Obote, appalled by his brutality.

Eventually in the war, there was deep factionalism within Obote’s army. The army was mostly Acholi, but Obote, a Langi, provided his own group more affirmative action for key military & government roles, alienating the Acholi.

Resentment grew, leading many Acholi soldiers to desert Obote. In July 1985, two disillusioned Acholi officers, General Tito Okello and Lt. General Bazilio Olara-Okello (not related), led a coup that overthrew Obote, who fled to exile in Zambia. However, the fighting continued, and Uganda was left in economic ruin, ranked among the world’s poorest nations. By the war’s end, 150K people fled and 100K-500K people died in this war. Obote’s 2nd term was arguably more brutal than Amin’s reign. In addition, HIV/AIDS started rampaging Uganda by 1985.

The Okellos (1985-1986)

General Basilo Olara-Okello held power in Uganda for only two days before handing it to General Tito Okello.

Despite this change, Museveni continued guerilla attacks, distrustful of the Okellos, who sought peace talks in Kenya while killing Museveni’s Southern civilian base. Ethnic factionalism persisted under the Okellos until the Ugandan Bush War ended with Museveni’s capture of Kampala in January 1986, forcing the Okellos to flee to Sudan

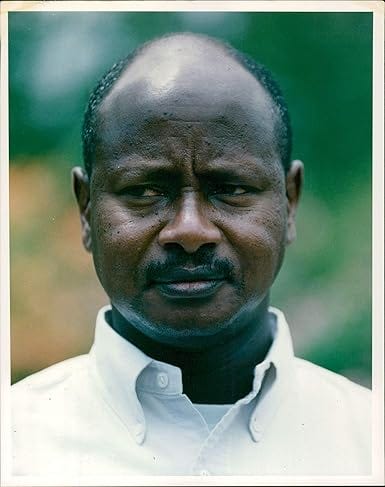

Yoweri Museveni (1986-Present)

The Politics of Museveni

Socialist Roots:

Museveni went to University of Dar es Sallam in Tanzania, which was a hotbed of socialist, Pan-African thought.

He was initially a revolutionary, Pan-African, Marxist-Leninist with anti-imperialist leanings. Museveni admired thinkers like Karl Marx, Lenin, and Nyerere. He was taught by the Marxist-Afro Guyanese thinker, Walter Rodney, who wrote the book “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa”. He even fought with the communists in Mozambique to evict Portugal.

Ideological Evolution:

However, by the time he assumed power, he became a “Leninist without the Marxism”. Walter Rodney died in 1980, so Rodney did not live long enough like Museveni did to see the shortcomings of Rodney’s socialist policy suggestions (nationalization of resources, self-reliance, resisting Western economic institutions) in places like Machel’s Mozambique, Derg Ethiopia, Nyerere’s Tanzania, Siad Barre’s Somalia, and more. Museveni recognized the failures of state-owned enterprises under previous regimes and witnessed the global collapse of communist governments. He embraced Leninist ideas, like rejecting multiparty democracy. However, he rejected Marxism, favoring aspects of capitalism instead.

Power Consolidation:

When Museveni came to power in 1986, he implemented a "no-party system," arguing that Uganda, as a rural peasant society, lacked the economic interest groups that would support a healthy multiparty system. Instead political loyalties were often driven by ethnic, regional, and religious ties, which he claimed led to strife and distracted from economic issues. As a result, Museveni curtailed the powers of political parties (no public rallies, no organized congresses, no nominating candidates, no campaigns). He didn’t allow elections until 1996, otherwise he would have lost Western aid.

Development Strategy:

At the heart of Museveni’s early governance was executing his the Ten-Point Program, a development framework aimed at revitalizing Uganda’s shattered economy and infrastructure. This program prioritized access to basic needs like clean water, healthcare, literacy, rural development, and women’s empowerment. The program achieved some notable gains, particularly in healthcare and education. Yet, corruption among officials remained a significant hurdle, with Museveni often dismissing high-ranking bureaucrats accused of embezzlement.

Tribal Politics and Restoration of Traditional Kingdoms:

In 1993, Museveni allowed the re-establishment of traditional tribal Kingdoms, except the Ankole Kingdom, to which Museveni himself belonged, fearing that an Ankole monarchy would dilute his authority. The move was extremely popular which gave Museveni legitimacy; however, the Kings were restored as “cultural leaders”, and were told to stay out of politics. Unfortunately, top political leadership in the army, public sector and government was still mainly Ankole.

The Economics of Museveni

In the late 1980s and 1990s, Uganda under Museveni was often hailed by Western donors as a success story for foreign aid, becoming a "donor darling." Museveni received significant aid and concessional (below market) loans from the IMF, including a structural adjustment loan focused on export diversification. He and the IMF implemented the 1987-1991 economic rehabilitation program, which liberalized Uganda's coffee market. Now as of 2022, Uganda sells $750M in coffee, ranking 16th in the world.

In the early 90s, there was an international coffee bean price crash. Thus, Uganda couldn’t pay its debt, so Museveni sought out massive debt relief from the West.

Commercial Debt Relief from the World Bank. The World Bank executed a debt buyback, where commercial loans were purchased from banks at a fraction of their value, providing debt relief to Uganda while international banks had to take a hit on their portfolio.

Bilateral Debt Relief from the Paris Club. Then, the Paris Club, rescheduled Uganda's bilateral debt in 1993. 33% of Uganda’s debt now had extended repayment terms and had lower interest rates, while the remaining 67% was written off completely.

Multilateral Debt Relief from the World Bank. Uganda then became the first country eligible for the IMF's Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative, which linked debt relief to poverty reduction plans. Museveni's Poverty Reduction Strategy focused on universal primary education and healthcare, helping to improve literacy rates and reduce HIV prevalence. By executing on so many social development goals, the IMF cancelled Uganda’s debts from the World Bank, IMF, and African Development Bank, freeing up more fiscal space to spend on healthcare, education, and rural development.

At the time, Uganda’s peak debt of $4.8B in 2004 was reduced to $1.3B in 2006.

Infrastructure:

Also, since Museveni was doing an excellent job reducing AIDS, illiteracy, and so on, the World Bank ignored his “authoritarianism” and provided cheap loans to Uganda for development projects like the Bujagali Dam, which was the World Bank’s largest development project in Africa at the time.

Museveni embraced IMF-backed privatization, viewing state-owned enterprises from the Obote and Amin era as a costly failure.

Old Strategy of Infant Industry Protection: Under Obote & Amin, these state owned enterprises aimed to protect "infant industries" in sectors like textiles (Uganda Textiles Board & Nyanza Textiles Limited), tourism (Uganda Tourist Development Corp), railways (Uganda Railways Corp), insurance (National Insurance Corp), banking (Uganda Commercial bank), airlines (Uganda Airlines), tea (Uganda Tea Growers Corp), sugar (Kakira Sugar Works), wires & cables (Kakira Cable Corp), meat (Uganda Meat Industries), paper (Paper Company), hotels (Lira Hotel), steel, utensils, & consumer steel products (Uganda Metal & Enameling Company, TUMPECO), and more, hoping Uganda could one day compete internationally.

While this strategy had succeeded in countries like Germany, Taiwan, Italy, Japan, and South Korea, poor execution in Uganda in the Obote & Amin era led to inefficiencies. State firms became “obese infants” — corrupt, unprofitable, delivered subpar services, and riddled with "ghost workers" on fabricated payrolls. Obote & Amin’s government was forced to borrow heavily to sustain these firms, which left Uganda with terrible firms and a huge debt burden.

Privatization: Over several decades, Museveni sold or dissolved 140 state-owned firms, though the process was rife with corruption, with assets often sold to well-connected individuals. A positive outcome was the return of South Asians expelled by Amin, bringing business expertise to Uganda. South Asian firms like Madhavi and Mehta groups came back and bought sugar, beer, steel, and tourism firms, contributing to 10% of Uganda’s GDP with 15K workers by 2007. (0.15% of the labor force).

Layoffs: The reason why the South Asian firms contributed a disproportionate amount of economic output with their small labor was because South Asians did mass layoffs and were highly efficient compared to other Ugandan firms. When Ugandan firms were state owned they were employment absorbers. Under South Asian management, many people were let go.

Bailouts: Unfortunately, privatization can fail too if private firms don’t have a growing market to buy their goods, can’t compete internationally or if management can’t execute. Museveni had to bail out Mehta’s and Madhvani’s businesses for them to remain afloat. However, Museveni did NOT bailout newly privatized Ugandan-African owned firms in meat, textiles, and paper.

Government Support: In addition, to keep firms afloat, Museveni also used his government to create a market for privatized firms. For example, Museveni made his government become the biggest customer of the privatized TUMPECO for metal products and he would order army shirts from the privatized NYTIL Museveni had to do this to keep Ugandan textile production afloat since Ugandan firms couldn’t compete with cheap textiles from China, Indonesia, or the Philippines.

Corrupt Bidding: However, privatization deals lacked transparency, they weren’t based on open market auctions like the IMF wanted. For example, Uganda Airlines was sold to Museveni's relatives despite higher bids from South Africa Alliance Air. Similarly, his brother, Salim Saleh, bought and resold Uganda Grain Milling at a profit, ignoring top bids from South African & Kenyan firms. Corruption was widespread, with firms often awarded based on bribes. Many government cabinet ministers who bought the firms did not know how to run private businesses.

Private firms ignoring social development: When Museveni privatized electricity, electricity access did increase, but the rural areas were neglected, so by 2010 Museveni partially renationalized the electricity sector.

A key lesson that I learned from combing through Uganda’s privatization documents is the importance of acquisition capital structure — the equity-to-debt ratio used in buyouts. Many investors who purchased Ugandan firms like Nyanza Textiles and African Textile Mills used high-yield debt. When these firms went to private hands they were liquidated since the interest payments were too high under private hands and frankly could not survive without government support.

Also, some Ugandan government divestments seemed desperate and poorly considered. For instance, Uganda sold hotels to the Japanese food retail firm Showa Trading at below book value, only for Showa to default on its debt. Nearly all Ugandan state-owned businesses were sold below their net asset value, with the exception of Ugandan Meat Packers.

Overall, privatization had lackluster & mixed results, there’s plenty to critique. Uganda still doesn’t have a globally renowned national champion like a Samsung or TSMC, but privatization did help the country diversify export earnings away from selling almost exclusively coffee beans. By 1995, coffee's share of export earnings had dropped significantly, from 97% in the 1980s to 70%. By 2007, it accounted for just 20% of exports.

The Wars of Museveni:

Despite Museveni’s efforts to unite Uganda through decentralization (creating Resistance Councils) and volunteer development projects, several regions, especially the North, resisted Museveni’s rule as a Southern Ankole. Here were some of the insurgent groups:

The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA): The LRA was a more successful offshoot of a different crazy rebel group called HSM. The leader of LRA, Joseph Kony, sought to establish a theocracy fusing Acholi traditional beliefs with Christianity. The LRA gained infamy for child abductions, pedophilic sex slavery, and atrocities against civilians. Ironically, Islamist Sudan supported the LRA, as Museveni aided South Sudanese rebels led by John Garang and Salva Kiir. Despite multiple offensives, including Operation Iron Fist in 2002, the LRA continued operations in the Congo, South Sudan and Central African Republic, leading to tens of thousands of deaths and mass displacements.

West Nile Bank Front (WNBF): Comprised of Idi Amin loyalists seeking revenge. Museveni’s forces ultimately crushed the WNBF.

Allied Democratic Forces (ADF): An Islamic insurgency arising from Uganda’s marginalized Muslim minority loosely affiliated to the broader Tablighi Jamaat movement. Sudan, under Omar Al-Bashir, funded this group. The ADF bombed bars and restaurants. Like the LRA, the ADF found refuge in Kivu, eastern Congo after its defeat by Museveni’s forces in the 1990s.

By the late 90s-early 2000s, the LRA and ADF escaped to East Congo in the Rwenzori mountains.

The ADF is now part of Islamic State in Central Africa. They steal gold and other resources in Congo to fund their terrorism.

Museveni supporting Kagame:

Museveni provided substantial logistic support to Paul Kagame’s militia group of Tutsi refugees, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), to launch a war against Habyarimana’s Hutu Supremacist Rwanda, kickstarting the Rwandan Civil War (1990-1994) and the Rwandan Genocide (April to July 1994). Why did Museveni help Kagame? Kagame supported Museveni’s National Resistance Army to remove Obote and the Okellos, so Museveni wanted to return the favor. Also, Habyarimana posed a security threat to Uganda since he kept killing/exiling Rwandan Tutsis to Uganda. Museveni has worked with Paul Kagame since they lived in Tanzania in the 70s.

After the RPF’s victory toppling the Hutu government in 1994, 1.5 million Hutu refugees, including the Interahamwe, the genocidaires, fled to eastern Congo, including places like Kivu, sparking new regional tensions.

Congo War 1, aka, “The Great Lakes Holocaust Part 1”

Mobutu Sese Seko, the longtime inept ruler of Congo (then called “Zaire”), was widely unpopular and the country was a failed state. The currency was worthless, the country could not control its borders, and it had one of the lowest incomes on earth. Copper production, which was the mainstay of the country’s economy, had fallen from 450K tons in the 1970s to 31K tons in 1994. Cobalt production fell from 18K tons to 3K tons, and diamond production was cut in half.

After Kagame’s take over of Rwanda, Mobutu allowed the Hutu Rwandans to come inside his country, because the UN provided his country a refugee aid budget of $800M per year. However, Rwanda’s Hutu genocidaires carved out a mini-state in Kivu, East Congo, setting up their own administration, finances and system of control. The Hutu Rwandans regrouped their forces into military camps and stole French weapons in the UN designated “safe zone”. With those arms, the Hutu genocidaires launched their attacks in Rwanda in September 1994 and continued throughout 1995.

East Congo wasn’t just having Hutu militias attacking Rwanda, but also to the ADF & LRA attacked Uganda. With all these terrorist militias operating out of East Congo and attacking Rwanda & Uganda coupled with the fact that Mobutu didn’t even control his own country anymore since America stopped providing aid after the end of the cold war, both Kagame and Museveni saw Mobutu’s regime as a regional source of instability.

Both Kagame and Museveni felt that they had to find a puppet who could remove Mobutu, stabilize the borders, help them remove the destabilizing rebel groups operating in East Congo, and secure them access to Congolese gold, diamonds, copper, & cobalt.

Museveni knew a Congolese Marxist rebel/Warlord/Gold Smuggler named Laurent Desire Kabila, who sometimes lived in Uganda and wanted to overthrow Mobutu and take over Congo.

So Museveni and Kagame both backed Kabila’s government for their own respective interests. This kickstarted the first Congo war, which removed Mobutu and killed a quarter of a million Congolese in the process.

Due to the high Congolese death count, many Congolese unsupportive of Museveni or Kagame argue that these “security concerns” were pretext for both countries to steal Congolese minerals. To be fair, Congolese people have a point; Ugandan firms have been stealing Congolese gold for decades and we can tell because Uganda exports more gold than it produces while Congo barely exports any gold.

Concluding Thoughts

When Obote returned for his second term as president, he failed to reconcile with the groups who hated him. He just crushed opposition and relied heavily on his Northern Nilotic base, particularly among the Langi and Acholi. Museveni, ambitious as well, capitalized on the public’s resentment toward Obote, making his rise easier with his Bush War.

Many people say “Africa needs a Deng Xiaopeng or Lee Kuan Yew”. Museveni tried to be and still is that autocratic reformer, but his execution leaves much to be desired since Uganda is still a low-income country while neighboring countries like Kenya & Tanzania upgraded to lower-middle income status years ago.

In part IV, we will conclude by discussing Museveni’s interventions in the 2nd Congo War, South Sudan, & Somalia. We will also discuss the 2000s coffee boom, Uganda’s relationship with China, its discovery of oil and more.