Uganda’s Economic & Geopolitical History Part IV: Museveni’s Reign, Uganda-Congo-Rwanda Tensions, and High-Stakes Bets on Oil & EVs!

The Final Chapter in this Series: From Revolutionary Rebel to Status-Quo Ruler

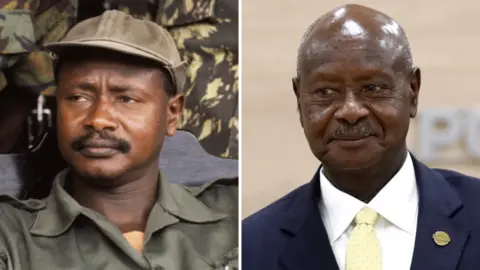

In 1986, Yoweri Museveni, newly victorious, declared, “The problem of Africa in general, and Uganda in particular, is not the people but leaders who want to overstay in power.” Ironically, 38 years later, he has remained Uganda’s President.

His grip on power stemmed from a belief that free & fair elections in Uganda would exacerbate tribalism, given the country’s bloody history of ethnic divisions. Although Uganda held elections every five years since 1996, the opposition consistently claims there were irregularities, ballot rigging, voter fraud, voter bribery and violent intimidation campaigns. In 2017, Museveni amended the constitution to remove presidential term limits, effectively enabling himself to rule for life if re-elected.

Today we will finish our series on Uganda.

Read Part I for Uganda's pre-colonial and colonial history, and Part II for its post-independence era. Part II culminates in Idi Amin’s failed war to conquer land in Tanzania.

In Part III, Museveni removed Obote. After consolidating power in Uganda, Museveni turned his attention to neighboring Rwanda, supporting allies like Paul Kagame, who led a Tutsi rebellion against Rwanda’s Hutu-led government. This intervention sparked a series of engagements that would entangle Museveni in the region’s geopolitics. In the First Congo War, he joined forces with Kagame and Laurent Kabila, targeting Rwandan and Ugandan rebels sheltering in Congo. This alliance, succeeded in removing Congo’s ruler, Mobutu, however this planted the seeds of future conflict.

In this final part of the series, I discuss the following:

1. Uganda & Rwanda’s Involvement in the 2nd Congo War (1998-2003)

2. Uganda’s Ruling with the International Criminal Court

3. Uganda’s Issues with the LRA, ADF, M23 & IS-CAP in East Congo

4. Uganda's Shifting Relations: Congo Strengthened, Rwanda Strained

5. Uganda’s economic bets on Chinese investment, Oil & Electric Vehicles

_________________________________________________

Congo: Congo War II or the “Great African War”

In 1998, a year into Congo’s new regime, the Museveni-Kagame-Kabila alliance began to unravel as many Congolese saw Laurent Kabila as a puppet of Museveni and Kagame, whose troops occupied Eastern Congo to combat rebels and take gold & diamonds.

Congolese were irate with Kabila, so in 1998, Kabila distanced himself from both Museveni & Kagame, expelling their military advisors & troops before they could neutralize local militias.

Without Ugandan and Rwandan forces in East Congo, the rebels (Allied Defense Forces, Lord’s Resistance Army, & anti-Kagame Hutu militias) renewed attacks on Rwanda and Uganda. Museveni and Kagame pleaded with Kabila multiple times to help neutralize these groups, but to no avail. Since Kabila would not listen to end the lawlessness in East Congo, Museveni & Kagame intervened again in East Congo. But, this time, Angola, Zimbabwe, Namibia and other African nations intervened to help Kabila, starting the 2nd Congo war.

Unlike their alliance in the First Congo War, Museveni and Kagame clashed in the Second. Museveni backed the rebel group called “Movement for the Liberation of Congo” (MLC) led by a warlord/millionaire businessman named Jean-Pierre Bemba. Meanwhile Kagame supported the Rally for Congolese Democracy(RCD), competing for spheres of influence in East Congo.

By 2000, Ugandan and Rwandan forces clashed in East Congo, particularly around the town Kisangani, which was a major center for diamond trade.

As you can see from the map, Kisangani is so far from the Rwanda-Uganda-Congo border that this fight shattered their pretense that their presence in Eastern Congo was for self-defense. Instead the Congolese people and the West then saw Museveni & Kagame as plunderers and exploiters.

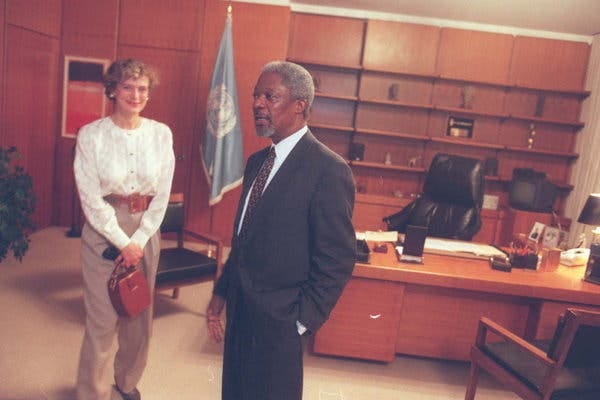

Outraged by the damage caused by Uganda and Rwanda over diamonds in Kisangani, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan urged the Security Council to sanction both countries.

The UN demanded their withdrawal from Congo and launched an investigation into the 'illegal exploitation' of its resources. Museveni and Kagame were cited as accomplices, accused of looting diamonds, gold, and timber. This fueled long-standing Congolese suspicions that they used Eastern Congo’s instability as a cover for mineral theft. The conflict led to 5 million Congolese deaths, marking it the deadliest war since WWII. However, most of the deaths were due to diseases, failure of basic state functions, and starvation amid the war. Also Laurent Kabila, was shot by his bodyguard, so his son, Joseph Kabila, took over with questionable legitimacy.

General Salim Saleh, Museveni’s brother & former head of the Ugandan army, used East Congo as his fiefdom. Gold from Congo became a major Ugandan export which still continues today.

The Ugandan army trained Eastern Congolese militias to act on its behalf, establishing rebel administrations in towns like Bunia, Beni, and Butembo to collect taxes and seize gold. A UN panel noted that this network operated through military intimidation, rebel-led local administrations, and manipulation of the money supply and banking using counterfeit currency.

In Orientale province, sometimes multiple Ugandan-backed militias clashed over control of gold, diamond, and coltan sites. In Ituri, Hema pastoralists and Lendu agriculturalists, both armed by Uganda, engaged in tribal war. Under President Joseph Kabila, Congo brought Uganda to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for blatantly occupying its territory and looting gold & diamonds.

Through the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement, Kabila secured the withdrawal of Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, Angola, and Zimbabwe from Congo. Although Uganda and Rwanda left later in 2003, their militias continued to plunder gold, boosting both countries' foreign currency earnings.

ICJ’s Ruling on Uganda’s Activities in Congo

In 2005, the ICJ ruled that Uganda had violated Congo’s sovereignty and was liable for mass deaths and resource looting, ordering reparations. In Museveni’s defense, he claimed that the invasion was for border protection. But this claim was dismissed amid the blatant resource looting and territorial occupation. Despite the war’s end, rebel groups like the “radical Christian” Lord’s Resistance Army and the “radical Islamic” Allied Defense Forces continued to launch attacks on Uganda from Eastern Congo.

Crushing the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA)

In 2005, the International Criminal Court (not the ICJ) issued arrest warrants for Joseph Kony and top leaders of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). Following failed peace talks between 2006 and 2008—where Kony ultimately refused to sign a peace agreement— Museveni recognized he needed regional allies to bring an end to the LRA threat.

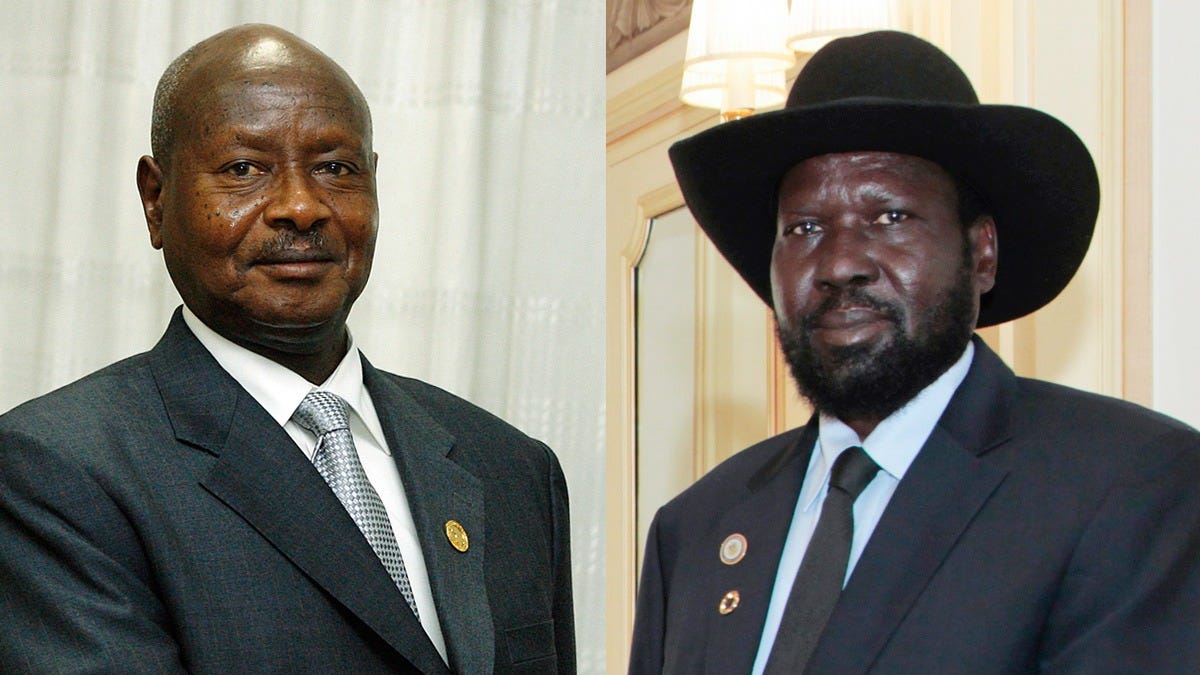

Ally 1-South Sudan: Museveni extended his support for South Sudan’s independence. He played a pivotal role in backing Southern Sudanese leaders like John Garang and Salva Kiir in their struggle against Sudan’s President Omar Al-Bashir. Kiir was an ally against the LRA.

Ally 2- America: Museveni also forged ties with the United States, offering Ugandan support in the fight against terrorism in places like Somalia and mercenaries in Iraq & Afghanistan. This partnership aligned Museveni closely with U.S. interests, and the Bush administration saw Museveni as a reliable ally in Africa.

“Ally 3”-Congo: Lastly, in Congo, President Joseph Kabila wanted to rid his country of the LRA’s destabilizing presence.

So December 2008, Uganda, South Sudan, Congo, and the United States joined forces to launch Operation Lightning Thunder, a coordinated military campaign targeting the LRA in northeastern Congo.

Although the campaign dealt a blow to the LRA, Kony managed to escape, and his fighters scattered to Central African Republic, Congo & Uganda, continuing to pose a threat in the region.

In 2011, President Barack Obama continued the pursuit by sending 100 American troops to help Uganda destroy the Lord’s Resistance Army. Their capacities were severely weakened by 2014. By 2017, Trump ended the mission to capture Kony, citing the LRA’s weakened state and reduced threat capacity.

Congo-Rwanda-Uganda Part III, The Rise of M23 Rebellion(2012-2013):

In 2012, the M23 group, comprising Congolese Tutsi, former Rwandan backed Congolese rebels, and discontented Congolese soldiers, launched attacks in Eastern Congo. The UN accused Uganda and Rwanda of funding M23, alleging they used the group to eliminate rebels hiding in the Congolese jungles & mountains, guard mines, control plantations, and tax trade routes.

Rwanda and Uganda denied the accusations, and Uganda threatened to withdraw from the UN-backed peacekeeping mission in Somalia in protest. In response, the UN decided to actively fight M23 in East Congo and authorized an international force to support the Congolese army against M23.

In 2013, 11 countries, including Uganda, signed a UN-mediated deal signing to refrain from interfering in Congo. Uganda mediated talks leading to M23’s (temporary) disbandment later that year.

2013-2019: Allied Defense Forces/ Islamic State in Central Africa (IS-CAP)

As the M23 conflict took place, the Radical Jihadist insurgency, the Allied Defense Forces (ADF), continue to attack Uganda via North Kivu, in East Congo. During this time, Congo and Uganda had a rapprochement and agreed to cooperate on intelligence sharing against the ADF.

Between 2019 and 2021, some ADF factions rebranded as the Islamic State’s Central African Province(IS-CAP), aligning with ISIS.

Now, as of 2021, Congo, Uganda, and the United Nations are collaborating to destroy the Islamic State of Central Africa in Operation Shujaa.

The operation is ongoing, with some issues. For example, the ADF & IS-CAP bombed Kampala in 2021.

In 2021, Uganda and Congo sign a bilateral trade deal focusing on cross infrastructure projects and roads connecting East Congo to Uganda, aimed at reducing the region’s isolation. As of 2024, the construction has been stalled due to the revived M23 inhibiting progress and unleashing chaos on East Congo.

It’s reassuring that Congo-Uganda relations have improved, with Uganda paying $65M of the $325M in reparations (The original amount of reparations asked was $11B, but the ICJ thought that amount was not justified.). However, Ugandan firms and artisanal miners continue to loot Congolese gold.

For example, a Belgium mining magnate, named Alain Goetz invested $15M in Uganda to establish the “African Gold Refinery (AGR)”, which exports gold to Antwerp and Dubai.

In March 2022, the U.S. Department of Treasury sanctioned Goetz and AGR, alleging that the refinery is just shell company to steal Congolese gold, using Uganda as a conduit. Despite the sanctions, Uganda’s gold exports exceeds its domestic production. Financial Times & The Economist reports on Ugandans smuggling Congolese gold routinely.

George Clooney’s nonprofit, the Sentry, revealed that in the 2020s, foreign investors collaborate with Uganda to smuggle over $500 million in Congolese gold annually. The gold is processed in Uganda, with firms paying militias like Mai-Mai Yakutumba and Raia Mutomboki to force Congolese artisanal miners to extract it. Militias compel miners to sell at $25 per gram, far below the market rate, with Congo’s army involved as well.

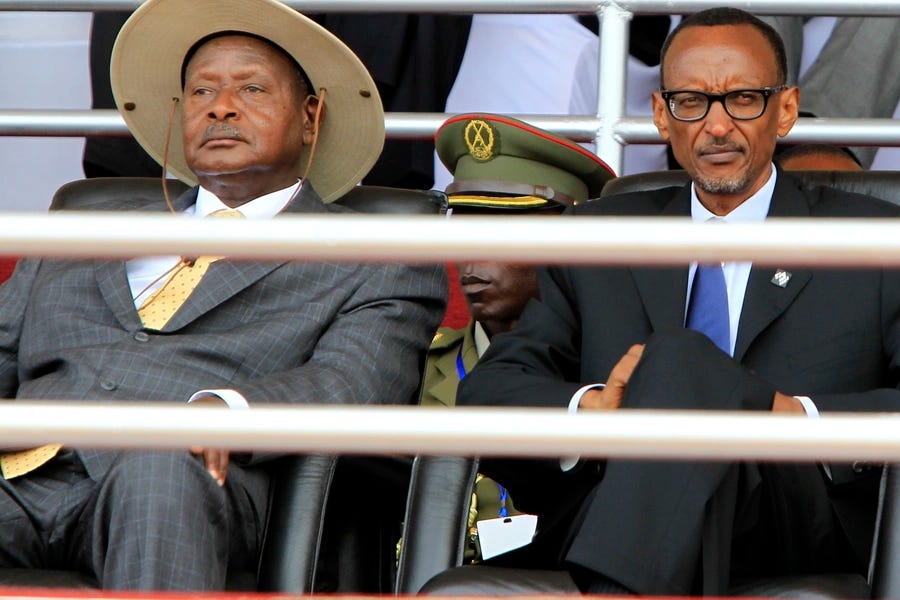

Uganda-Rwanda Rivalry

Since the Second Congo War, tensions have persisted between the two former allies who once helped each other rise to power. Both are said to be vying for influence in East Congo, though they present their conflicts under a different pretense:

Kagame was mad at Museveni for allowing members of the Rwanda National Congress & Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda, two anti-Kagame rebel groups on Ugandan soil. Meanwhile Uganda accused Kagame of spying his country.

In 2019, border tensions at the Gatuna-Katuna border led Kagame to close the crossing, disrupting trade. This impacted both economies, especially small and wholesale traders who depended on cross-border price differences to profit, ultimately hurting consumers as well.

By 2022, they reopened their border as they are trying to improve relations.

The “East African Federation”

East African countries are working to strengthen ties, yet Congo and Rwanda remain hostile. In 1967, Uganda was a founding member with Kenya & Tanzania in the East African Community. In 2007, Rwanda joined, and in 2022, Congo joined.

Regional integration remains challenging as M23 continues violence in eastern Congo. President Tshisekedi blames Kagame, who denies involvement, though UN reports implicate Rwanda despite Kagame's dismissal of these claims as baseless.

Other African Conflicts: Somalia & South Sudan

Somalia:

Uganda's success in killing Somali terrorists, aided by American training, made it a target, leading to the 2010 Al-Shabaab bombing in Kampala. Uganda is placing a key role in the African Union’s mission to stabilize Somalia.

South Sudan:

During South Sudan's post-independence civil war, Museveni backed Salva Kiir against his opposition and continues to provide him with security support.

Museveni’s Bets for Growth

Most of this article has been discussing the geopolitical entanglements Museveni has gotten himself into and stealing Congolese gold. But Museveni has ambitions that can be summed up in three:

1. Chinese investment

2. Oil

3. Ugandan EV manufacturing

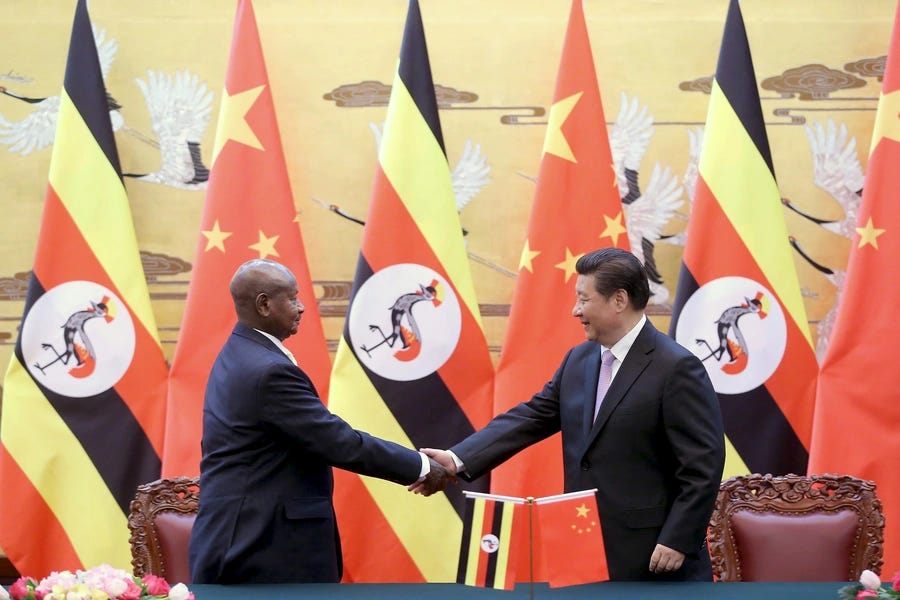

1. Chinese Investment

Museveni bristled at Western donors' criticism over the Congo wars, rigged elections, and spending on private jets. After receiving debt relief in 2005, he sought independence from Western aid by pursuing two strategies: first, he secured a credit rating to borrow from international investors via eurobonds, reducing reliance on Western loans. Second, he looked to China for financing, drawn by their non-interference stance.

Western-Scolding & Interference

For an example of Western scolding, in 2014, after Museveni signed an anti-LGBTQ law, the Obama administration urged the World Bank to halt low-interest loans and imposed sanctions such as installing travel bans on Ugandan officials, halting military cooperation, and withholding aid. In 2023, following a harsher anti-LGBTQ law, Biden expelled Uganda from the AGOA trade deal.

China’s Business

China does not believe in universal human rights, but believes each country has their own human rights. China’s Export Import bank lent for the construction of two hydroelectric dams and an express road between the capital city of Kampala and Entebbe, where Uganda’s international airport is situated.

Lastly, Chinese investment in Ugandan gold mining has grown, with firms like Wagagai Mining opening a gold refinery in 2024. Also, China’s National Offshore Oil Corporation is also involved in Ugandan oil extraction.

2. Oil

In 2006, Uganda found oil!

Unfortunately its been a nightmare to extract it.

The Uganda National Oil Company’s negotiations with foreign firms stalled over tax rates and the plan to build a local refinery to produce fuels, plastics, and fertilizers. Also, initially, Uganda considered routing the pipeline through Kenya, but opted for Tanzania's lower tariff ($12.2 per barrel compared to Kenya’s $12.6 to $15.9).

The COVID-19 pandemic further delayed progress, and some key investors, including Heritage Oil, exited the project. Also, Tullow Oil, a British company, also withdrew, selling its assets to the French firm TotalEnergies for $600 million.

Why? The answer lies in corruption: 42 government officials were caught red-handed accepting bribes from Tullow & Heritage Oil, securing $1.7M. Now, only French TotalEnergies and China’s SNOOC remain to help Uganda export oil.

Uganda has 6.5 billion barrels of oil, with ~1.5 billion economically recoverable. Being landlocked, Uganda will pay tariffs to transport the oil through Tanzania to access the coast.

"Economically recoverable" in oil markets means only 1.5 billion barrels can be profitably extracted under current conditions (around $70 per barrel) and current oil extraction technology. Without a technological breakthrough or a price rise above $70, only about 1.5B out of the 6.5B of Uganda's oil is viable. While Uganda’s total reserves match Azerbaijan's (23rd globally), its recoverable reserves align with Chad's (42nd). Uganda plans to begin selling commercial crude in 2025, producing about 200,000 barrels per day. If fully exported from January 2025, this would generate slightly under $4 billion annually for about 17 years.

Here’s my math in case you are curious:

For the lifeline of oil calculation: 1.5B barrels / (240K per day * 365 days per year) = 17 years

*Note: I assumed Oil would run 330 days of production because most oil operations have scheduled maintenance periods, emergencies, or other interruptions.

Selling oil would become Uganda's top source of foreign currency and government revenue. However, if solar or nuclear energy demand surges, reduced oil demand could lower oil prices, diminish Uganda’s government revenue, and shrink Uganda's economically recoverable reserves.

While oil will boost Uganda’s growth, it’s far from a UAE- or Guyana-scale boom, which exports over $100B and $16B in oil, respectively, compared to Uganda’s projected $4B.

3. Electric Vehicle Manufacturing

Museveni’s army runs the National Enterprise Corporation (NEC), a state-owned investment firm with stakes in vehicles, road construction, and more, though it remains unprofitable.

The NEC is betting on the electric vehicle industry through its joint venture, Kiira Motors, with Makerere University, Uganda’s premier university. Founded in 2011, Kiira Motors is still unprofitable, sustained by government subsidies, with hopes for profitability by 2030."

While promising, Uganda has a history of failed state-owned firms. They produce the car but still need to build brand awareness, supply chains, distribution, customer service, and after-sales support. Execution is key.

As of 2024, Uganda’s finance minister is negotiating a $1B interest-free IMF loan under the IMF’s Extended Credit Facility. The IMF recommends privatizing loss-making state firms, raising interest rates, and increasing indirect taxes.

Uganda’s Central Bank currently has $3.25B in foreign reserves. Since Uganda imports roughly $0.9B a month, that leaves Uganda with 3.6 months of import coverage — slightly above the 3-month emergency threshold.

This loan aims to prevent a balance of payments crisis while Museveni initiates reforms, though their success remains uncertain. After all, Uganda has taken 12 IMF loans in total and its currently the 17th poorest country on earth as of 2023.

Concluding Thoughts

When Museveni came in 1986, Ugandan GDP per capita was $253.3 (or $703.16 in inflation adjusted 2023 prices). By 2023, Ugandan GDP per capita risen to $1014. This means that, since Museveni’s rule began, inflation-adjusted incomes in US dollars have yet to double for the average Ugandan. Though its not entirely his fault. Uganda’s continuous wars & conflict since Amin & Obote have stalled economic growth. See graph below:

During that same period (1986-2023), in inflation-adjusted incomes and expressed in US dollars, Kenya’s per person GDP has doubled, India’s has nearly tripled, and China has increased inflation-adjusted incomes 16-fold!

Food production is a major challenge in Uganda. With a rural population of 73% and a high birth rate (4.3 children per woman), local farmers’ moderate yields of wheat, corn, millet, and rice cannot keep pace. Commercial farming initiatives have failed, and smallholder investment is limited by communal land ownership, which lacks clear property rights.

Uganda’s development is mixed—falling short of Botswana or even Ivory Coast but showing better prospects than Mali or Burkina Faso.

The return of exiled Ugandan Indians has created 100,000 jobs in tea, sugar, and construction. Combined with oil exports and a potential boost from EV production, Uganda could reach lower-middle-income status by 2030 if well-executed.

Why don't you call Ivory Coast, Cote d'Ivoir? I am just curious (It's more fun to call it the second way in my opinion).