From Communism to Oligarchy: How Russia’s Privatization Failed

From Communism to Gangster Capitalism

Some people, like Bernie Sanders, liken Russian oligarchs to today’s tech giants, but to me, the comparison falls flat. There’s a big difference between a billionaire who builds something of value and a billionaire who acquires state owned enterprises. Building and selling products or services that people, corporations, and governments actively want is different from buying government-created enterprises and then extracting rents from them.

What’s interesting is that the combined net worth of Russia’s top oligarchs is about $186 billion—less than the fortunes of Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos alone.

Soviet Union’s Slow Death

In 1979, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) invaded Afghanistan, a decision that proved to be a massive drain on resources. At that time, the USSR was the world’s top oil producer(11.5M barrels per day), relying on oil for over 50% of its foreign currency earnings to import wheat, machinery, and other goods. By the 1980s, West Siberian oil production had slower growth, and the 1986 oil price collapse, driven by increased oil production in American Alaska, the British North Sea, and Saudi Arabia, created an oil glut. With high breakeven costs, the Soviets faced losses, ran out of foreign currency, and struggled to import food and equipment.

Systemic inefficiencies led to food shortages, public dissatisfaction, and stagnation. The Afghan war further strained resources and morale, accelerating the Soviet Union's decline.

The Soviet State-Owned Economy

The Soviet economy was rigidly centralized and plagued by inefficiencies.

No Private Business: Private enterprise was banned, except for small activities like selling surplus food from personal gardens in “kolkhoz markets” (collective farm markets). Violators faced harsh punishments.

Price Controls: Prices for goods were set by government fiat instead of businesses. While basic necessities were kept artificially cheap, frequent shortages were the tradeoff.

State-Owned Banks: Banks merely collected savings. Bureaucrats determined loans and allocated funds, often without accountability or monitoring.

Government Owned Enterprises: State enterprises produced goods based on output quotas set by bureaucrats. Enterprises did not make decisions. They were told what to produce by government bureaucrats. Inputs like raw materials, labor, and machinery were allocated without consideration of actual needs (which would be reflected in market prices), often leading to shortages of essentials and surpluses of industrial goods. This is what economists like Ludwig von Mises and Fredrick Hayek called the “Economic Calculation Problem”.

These inefficiencies fueled a thriving black market. Factory managers often traded surplus materials illegally to gain perks beyond their modest salaries. Meanwhile, ordinary Soviet citizens relied on unofficial channels to acquire goods like American Levi's jeans or foreign currency.

Gorbachev’s Reforms

In a bid to save the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev introduced reforms under perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (openness). However, Deng Xiaoping of China thought this was suicidally idiotic for the Soviet Union to open political & economic freedoms simultaneously. Deng did economic reforms first.

Some of Gorby’s economic reforms:

Leasing State Factories: Workers could lease factories during off-peak hours to produce goods privately. However, fear of policy reversals deterred participation.

Allowing Foreign Investment: In 1987, Western firms were allowed to partner with Soviet state enterprises to gain access to the Soviet market. Pepsi and McDonalds were among the first investors in the Soviet market.

Legalizing Cooperatives: Small private businesses called cooperatives were legalized, catering to needs unmet by the state. These cooperatives often imported computers, ran lotteries, or traded surplus materials. Some even ventured into exporting commodities, bypassing inefficient state trade agencies. However, some operated as facades for underground activities, and many early cooperative entrepreneurs later became oligarchs.

The Rise of Soviet Black Market Millionaires

The black market thrived long before Gorbachev's reforms. Entrepreneurs operated in the shadows, smuggling goods, providing private services, or exploiting inefficiencies. But once glasnost & perestroika started, the Soviet Union had legal millionaires. Among them was the Armenian-Russian Artyom Tarasov, who became the first legal millionaire of the Soviet Union.

Exploiting Inefficiencies: Tarasov saw opportunities where the state failed. In one instance, a state owned Soviet Ukrainian oil refinery, unable to use surplus fuel oil due to a weak winter, dumped fuel oil into forest pits (Who said only capitalism destroys the environment?). Tarasov convinced the refinery to sell the oil to him instead, halting environmental damage.

Breaking State Monopolies: Tarasov then sold the oil to commodity traders like Marc Rich + Co, bypassing Soviet trade agencies. By leveraging this relationship, he disrupted state monopolies on exports, becoming a pioneer in private oil trading in the Soviet Union.

How Pepsi Helped Destroy the Soviet Union’s Navy:

By the late 1980s, the Soviet Union, still lacking foreign currency, struck a bizarre new barter deal: Pepsi traded its drinks to the Soviet Union for 17 submarines, a cruiser, a frigate, a destroyer, and vodka. Pepsi sold the naval fleet for scrap, prompting PepsiCo’s chairman to quip to President George H.W. Bush, “We’re disarming the Soviet Union faster than you are.”

Imagine reading this on the New York Times as a Soviet loving Communist:

The Soviet Union’s Collapse: A Perfect Storm

In the 1980s, collapsing oil prices dealt a severe blow to the Soviet Union, which heavily depended on oil exports. As one of the world’s largest producers of oil, metals, and grain, the USSR relied on state-owned agencies—Raznoimport (metals), Exportkhleb (grain), and Soyuznefteexport (oil)—to manage its limited foreign trade. But this system was crumbling. The Soviets ran out of foreign currency to import goods. New Soviet commodity traders were taking business away from the government agencies and sending their money to Swiss and Cypriot banks.

Failed State Dynamics

Collapsing Industry: State-owned enterprises were told what to produce and where to send it, relying on government-supplied raw materials and rubles for wages. As the system broke down, mines, refineries, and smelters ran out of money to pay workers or buy supplies. The Soviet Military Industrial Complex enterprises died as its biggest customer, the state, collapsed. Reagan’s “Star Wars” missile defense program further terrified Soviet leaders, exacerbating the sense of military inferiority.

Losing in Afghanistan: The American backed Mujahadeen (like Osama Bin Laden) were able to push back the Soviets.

Rising sense of Nationalism: The USSR’s status as a multi-ethnic federation made it vulnerable to nationalist movements. By the late 1980s, independence movements in the Baltics (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), Ukraine, and Georgia threatened Moscow’s control.

The Death of the Soviet Union

On Christmas Day 1991, the Soviet Union ceased to exist. Mikhail Gorbachev resigned, leaving Boris Yeltsin as president of the newly independent Russian Federation. The Soviet Union splintered into 15 countries:

Baltics: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania

The East Slavic Core: Ukraine, Belarus, Russia

The Caucasus Region: Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia

Central Asia: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan

Moldova

Yeltsin’s Presidency

Yeltsin’s Shock Therapy: Russia’s Radical Economic Transition

In the early 1990s, Boris Yeltsin launched shock therapy to dismantle the planned economy and transition to capitalism. Supported by a $24 billion aid package from the West, the IMF, and the World Bank, this ambitious program aimed to privatize 17,000 state-owned enterprises, deregulate prices, and restructure the economy. However, the chaotic execution led to hyperinflation, corruption, and the rise of oligarchs, leaving deep scars on Russian society.

Economic Collapse and Hyperinflation

With IMF advice, by 1992, price controls were lifted, and the ruble was allowed to float, triggering hyperinflation that peaked at 2,330% that wiped out life savings. Russia reduced inflation to below 1,000% by late 1993, below 100% by 1996, and reached single digits in early 1998, just before the Russian financial crisis…

Basic goods like milk and bread became unaffordable, but the tradeoff was that shortages disappeared. From 1992 to 1997, since the ruble’s value was determined by supply and demand of the currency, the ruble lost 99% of its value against the dollar. However, by 1995, the rate of Ruble depreciation decreased. Russia anchored the ruble to the dollar in a currency band. Russia had to sell foreign reserves to maintain the ruble between 4000-6000 rubles to a dollar.

Monetary Tightening

In order to bring down inflation, Russia’s central bank did extreme monetary tightening by rapidly hiking interest rates. The central bank had interest rates as high as 150% in the 90s to curb inflation.

Privatization and the Voucher Scheme

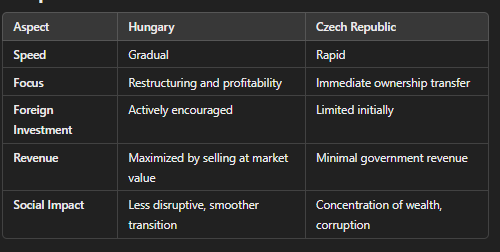

Yeltsin’s Finance Minister, Anatoly Chubais, considered two privatization models: Hungary’s gradual, foreign investor-friendly approach and the Czech Republic’s rapid citizen, voucher-based system. Below are their pros and cons:

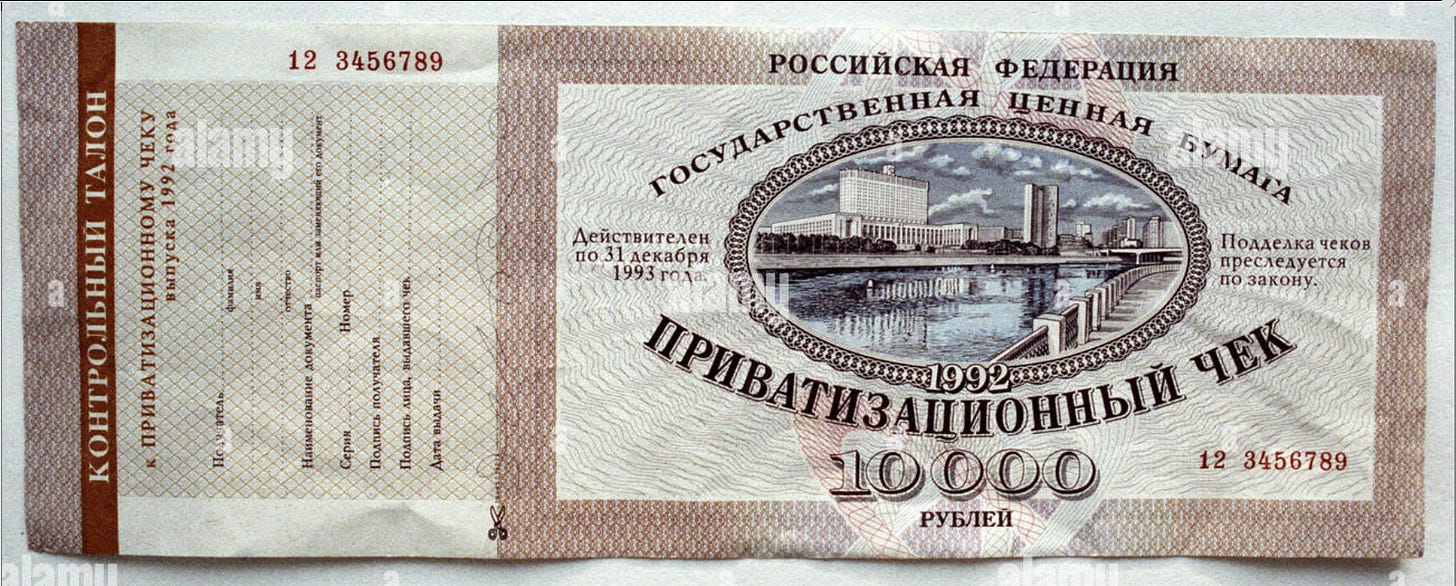

Chubais favored Hungary’s gradual approach, but Russia’s legislature rejected it, opting instead for the Czech-style voucher privatization scheme. Each citizen received a voucher representing a share in privatized industries. Valued at 10,000 rubles ($63), the total worth of state-owned firms was set at $9.1 billion ($20 billion in 2024 terms). If you are wondering why the value of Russian assets were so low, its because the vast majority of the Soviet Russian state owned enterprises were virtually bankrupt and poorly performing, killing their valuation.

The Russian Congress adopted the Czech model, hoping to create "People's Capitalism," boost efficiency, and prevent a communist resurgence. Under this scheme, employees, managers, and directors received substantial shares in state-owned firms, with the remaining shares distributed to the general public. The Russian state still owned minority & major stakes in “strategic” sectors like oil, gas, aerospace, and more.

Russian privatization succeeded with small businesses, transferring ownership of 85,000 cafes, shops, and restaurants to managers and employees, often for free. Small business growth was the best part of privatization. Apartments were also privatized, creating many private homeowners.

The issue with privatization came at scale with larger firms. The problem with large-scale privatization in Russia was the lack of a middle class with savings, as inflation had wiped out most Russians' wealth. Unlike Thatcher’s privatization in the UK, Russia barely had any institutional investors, leaving vouchers to be amassed by banks owned gangsters, ex-Soviet officials, and factory directors.

Here’s where large-scale privatization faltered:

Inflation and Poverty: Most Russians, desperate for cash & unfamiliar with stock markets, sold their vouchers cheaply. Sometimes for jeans or vodka.

Concentration of Vouchers:

Many Factory managers threatened to fire their employees unless they sold their vouchers to them.

Many black-market entrepreneurs/Russian mafia thugs made up “voucher funds” to invest people’s vouchers. They were just facades to steal these shares, consolidating ownership into the hands of a few. Sometimes people provided counterfeit vouchers.

Government officials would secure state owned assets at rigged auctions as well.

Lack of Competition: The problem with partial privatization was that Soviet-era monopolies, known for their massive size ("Gigantomania"), weren’t broken up. Privatization left these huge monopolies without competition, and shared ownership with the state provided little incentive for efficiency enhancements.

Institutional Weakness: The lack of legal frameworks and rigged auctions enabled insiders to buy assets, such as Norilsk Nickel and Yukos Oil, at absurdly low prices.

The Rise of Oligarchs and Corruption

Privatization consolidated wealth into the hands of a few, creating oligarchs:

From Vouchers to Banks to Business Empires:

From Black Marketeer to Banker to Oil Oligarch to Being arrested by Putin - Mikhail Khodorkovsky In post-Soviet Russia, black marketeers, ex-Soviet officials, and factory managers amassed vouchers during privatization. These vouchers were used to buy small enterprises, which, after generating profits, became stepping stones for forming business networks and banks. By the mid-1990s, over 5,000 banks had sprung up, many created through these informal networks. This created the Oligarchic class.

One prominent figure, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, transitioned from black market trading to founding Menatep Bank. Leveraging his financial clout, he secured a controlling stake in Yukos Oil, one of Russia's largest energy firms, despite not offering the highest bid. This acquisition, like many others, capitalized on the undervaluation of state assets during rigged auctions, showcasing the systemic manipulation that defined Russia’s privatization.

Loans-for-Shares Scheme (1995):

Facing a large budget deficit ($800M at the time), Yeltsin auctioned shares in key state enterprises (e.g. Norilsk Nickel, Surgutneftegas, Novolipetsk Steel, etc) to oligarch-controlled banks in exchange for loans. The auctions for government-owned shares were rigged, with banks both running and bidding in the auctions, stifling competition. This allowed them to acquire undervalued state firms at minimal cost.

However, many firms, like Norilsk Nickel (losing $800M annually) and Yukos Oil (burdened with debt), were deeply unprofitable. Despite inviting foreign investors & businesses like George Soros, German Mercedes, Wall Street Banks, and South Korean Daewoo, the vast majority of foreign investors avoided Russian assets, and 4 big firms received no bids.

Ultimately, the government raised little revenue from the scheme, whether due to poor valuations for terribly run firms and/or flawed auction processes. For example, Norilsk Nickel, which earned $1.2 billion in revenue 1999 after privatization, was partially privatized (a 40% sell off) at a valuation of $170 million, which some people point to as proof of undervaluation. By 1996, the government collected only 14% of the year’s targeted privatization revenue of $2.2B.

Yeltsin maintained price controls for oil, gas, and other commodities, enabling officials and gangsters to buy cheap and sell abroad for massive profits. Jeffrey Sacks, an Economist who worked as an independent advisor to the Russian government in the 1990s, wrote in NYT:

“Russia's vast natural resources provided unparalleled opportunities for theft by officials. Oil, gas, diamond and metal ore deposits were nominally owned by the state and thus by nobody. They were ripe for stealing -- or for "spontaneous privatization," as Russians cynically call it.”

Capital Flight

The IMF’s push for capital account liberalization (removing restrictions for investment, lending, and converting currencies) opened the floodgates for capital flight, with rich Russians funneling money to Swiss, Cypriot, British banks. This drained the economy of domestic investment and financial stability.

Yeltsin's new Privatization & 1996 Reelection

In 1996, Yeltsin faced a tough re-election battle against Gennady Zyuganov, leader of the Russian Communist Party, who capitalized on widespread disillusionment with unemployment(10%!), poverty, and hyperinflation by promising renationalization and Soviet-style policies.

To secure victory, oligarch-controlled media discredited the communists, while the U.S., under Clinton, provided cheap loans and grants to support Yeltsin. Boris used Western aid to boost public worker wages, pensions, and subsidized loans for farmers, effectively "buying votes."

Yeltsin also shifted the privatization of 6,000 remaining firms to regional governments, deflecting blame for unpopular policies. While Yeltsin is credited with "saving democracy by defeating communism," his methods undermined the integrity of the election.

After winning election, Boris negotiated payments for $93B Soviet debt with the Paris Club (mainly Western Nations, Japan) & London Club(Mainly Western Banks).

1998 Russian default

The fall in oil prices from 1990 to Aug 1998, along with declines in other commodities like gold, gas, nickel, copper, and more hurt Russian industry profits. When Russia and other resource-rich, ex-Soviet states (e.g., oil & gas rich Azerbaijan & Turkmenistan. Oil, iron, coal & copper rich Kazakhstan) joined international commodity markets, their supply crashed global prices. This reduced government revenue from Russian state-owned commodity firms, worsening the deficit.

To finance its spending, Russia issued bonds heavily reliant on foreign investors. However, the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis reduced demand for raw materials since Japanese & South Korean firms were struggling and weren’t buying Russian resources at previous rates. In addition, the crisis prompted investors and firms to withdraw from emerging markets like Russia. By converting rubles to foreign currencies, the ruble’s value was dropping. Since 1995, Russia was defending its ruble against the dollar, and Russia sold dollar reserves to defend the ruble, until it ran out of reserves to do so. If you look at the graph below, since 1995, Russia already had less than 3 months of reserves, which is emergency status for any country that anchors it currency to the dollar. By 1998, it had 1.4 months remaining.

By July 1998, it was obvious that Russia could not pay its debts. Due to Ruble currency devaluation to the dollar, dollar denominated interest payments became unbearable. Interest payments were 40% of Russian government revenue. The Clinton administration tried saving Russia by telling the IMF to quickly give Russia a $5B emergency loan. Unfortunately, Yeltsin’s inner political circle and family stashed the $5B in Cayman Island & Swiss Banks.

By August 1998, Russia devalued the ruble, defaulted on $40 billion of foreign debt, and declared a moratorium on payments, signaling the collapse of its financial system. The ruble lost 83% of its value in a year after the default. The stock market also collapsed 94%.

The economy hit rock bottom: from 1991 to 1998, Russia’s GDP was cut in half with mass poverty, homelessness, and social dysfunction. Russia's recovery in the 2000s came under Putin, who capitalized on a China-driven global commodity boom.

Conclusion

Some economists argue that prices, private property, profits, competition, and incentives are the keys to economic success, ensuring firms produce efficiently at the lowest cost. While appealing, this view overlooks a crucial ingredient: institutions.

Institutions provide the legal frameworks for enforcing contracts, resolving disputes, managing bankruptcies, safeguarding deposits, and ensuring fair competition. Functioning markets require a functioning state to establish and uphold these rules. Without strong institutions, there are no shortcuts to building a functioning market economy.

In Russia’s case, reform was inevitable. The Soviet Union’s economy was beyond redemption, but the method of reform was critical. There were two main paths (with tons of room in-between):

Option 1:Better-Implemented Shock Therapy

Former communist countries like Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and others adopted rapid market reforms alongside institutional development(transparent privatization, strong investment laws, and more), achieving faster and more stable recoveries. While these transitions were still painful, they benefited from better execution. Ironically, the lack of significant natural resources in these countries may have shielded them from the rent-seeking behavior that plagued resource-rich nations like Russia.Option 2: Gradual Sequencing: China pursued a gradual, experimental approach to reform, prioritizing controlled economic liberalization under strong state guidance. This incremental strategy allowed China to test policies and adapt to challenges before fully embracing market forces.

Russia’s failure wasn’t in the idea of reform itself but in its chaotic execution. Shock therapy, implemented without strong legal foundations or controlled experiments, devolved into a free-for-all, fostering corruption, capital flight, and the rise of rent-seeking oligarchs. One can only wonder how different Russia’s trajectory might have been with a more structured approach.

While the IMF certainly has its faults, it’s worth noting that IMF economists also advised countries like Romania, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic during their transitions. In these cases, government officials adapted the guidance to their own contexts, achieving post-communist reforms without default. Blaming the IMF solely for the concept of shock therapy overlooks the nuance—there are multiple examples where such reforms were executed with greater success.

Russia took 13 years to surpass its 1989 communist-era income levels, compared to just 6 years for Poland and the Czech Republic, 7 for Romania, 8 for Slovakia, and 9 for Hungary.

If you're interested in exploring how China's economic reforms differed, check out my pieces How Deng Xiaoping of China outsmarted the IMF or How China is Different from the Soviet Union.

Nice overview of a terrible saga.

Russia in the 1990s was probably the greatest economic and societal collapse of a sizable nation in the modern era. The collapse was far bigger than the Great Depression and it happened during a time when virtually every Russian had a recent memory of being a respected and feared superpower.

With hindsight, I am not sure that there was a strategy that had a high chance of avoiding this outcome.

The Soviet economy was so command-driven and there were no people who had a living memory of anything else. No one other than black marketeers had any idea how to run a business. In Eastern Europe older people still had some knowledge of how markets worked and the Soviet occupation never had real moral legitimacy.

Also the Soviet economy was largely based on military production that was no longer needed, and as you stated the massive oil, gas and minerals made it easy for political leaders to scoop up soon-to-be valuable natural resources. Plus oil prices were very low in the 1990s, so there was little revenue there.

China does not offer a model as it was largely an agricultural economy. Farmers know how to farm, if you just leave them alone. The Soviet economy was an industrial economy and that industry was largely not sustainable.

And any Western aid would have been wasted. Western experts had no better idea how to transform a Communist economy into a capitalist economy than the Russian people. Nothing like it had ever happened.

Sadly, I just don’t see an alternative outcome.

Great article, I also did an assignment on Russian oligarchs (just extended it to today) and came up with similar conclusions. However, I will disagree with the definition of the oligarch; an oligarch for me is a wealthy individual who is tied to a government, as at least shown in Moscow. Considering that in DC we see similar phenomena; big business lobbying for friendly regulations, corporations spending unlimited amounts to influence election results, and an increasing gap between the rich and the poor, I would argue the States are indeed an oligarchy to an extent. And I am not saying every US tycoon is an oligarch like not every Russian businessman is an oligarch (there are many of them living in Cyprus after 2022 for instance), I am only explaining that many US billionaires aren’t different from their Russian counterparts (Musk could be also viewed as a recent example).

Another great reminder is Larry Fink’s recent remarks that the election outcomes don’t matter: https://www.businessinsider.com/larry-fink-us-election-no-impact-markets-long-term-2024-10