How Deng Xiaoping of China outsmarted the IMF

Did you know that China took two IMF loans?

Today, you'll read about how, in the 1980s, Deng Xiaoping's government in China borrowed from the International Monetary Fund(IMF) twice — an astonishing fact, considering that as of 2024, China’s foreign reserves ($3.3 Trillion) far exceed the IMF’s total assets of $1.3T.

Recap of My Other Chinese Pieces

This is my fourth article on China.

My first, “China’s Ancient & Modern Relationship with Africa”. explored China’s ancient & medieval connections with Egypt, Morocco, East African Swahili Afro-Arabs off the coasts of modern day Kenya, Tanzania, & Mozambique, and Somalia through various dynasties.

My second, “The Future of the Chinese Belt & Road Initiative in Africa” examined China’s evolving lending strategy in Africa. I challenged the “Debt Trap Diplomacy” narrative, highlighting how Chinese banks are now more selective, focusing on profitability rather than expansive lending. The graph below shows how Chinese lending in Africa has sharply decreased since 2016.

My third and most popular article, “How China is Different from the Soviet Union” delved into how the Politburo in Beijing differed from Moscow. While China remains politically centralized, it’s highly decentralized economically—local leaders, like provincial mayors, wield significant control akin to running mini-nation states, with the Communist Party offering overarching guidance. Interestingly, during the Deng era, there was even consideration among political elites to drop the “communist” label altogether!

Historical Context

After the Communist Party of China took over the Mainland in 1949, following the Chinese Civil War, Mao Zedong’s government was considered a “rouge state” by the United States. At this time, China’s seat on the United Nations Security Council was held by the Nationalist, Kuomintang (KMT) government, which had fled to Burma and Taiwan, which became the new headquarters of Nationalist China.

Through a clever use of soft power in the non-Western world — giving aid to countries like Zambia & Tanzania and providing doctors to other to countries like Afghanistan, Chile, & Turkey, even when his own people were starving — Mao was able to shore up international legitimacy from most of the non-Western aligned world in Africa & Asia.

Even most of Europe thought that saying that Taiwan was “True China” was deeply illogical. By 1971, thanks to UN Resolution 2758, Beijing finally took its UN seat from Taipei.

When Nixon recognized the rift between China and the Soviet Union, he met with Mao, laying the groundwork for future U.S-China relations. Ford and Carter, built on that relationship, with Carter recognizing Mainland China as the “real China” while being “strategically ambiguous” on the final status of Taiwan.

In the final years of Mao’s life, the Gang of Four— led by Mao’s Wife and three others — exerted significant influence over China’s politics, pushing for maximum leftism, though they did not fully control the government.

Mao died in 1976, and chose Hua Guofeng (“Wa Gwo-fung”), as his successor, a “moderate communist” compared to the Gang of Four. With the support of the military leader Ye Jianying (“Ye Jyen-eeng”), Hua removed the Maximum Leftism of the Gang of Four. Meanwhile, Deng gradually maneuvered his way into power, becoming China’s paramount leader by 1980.

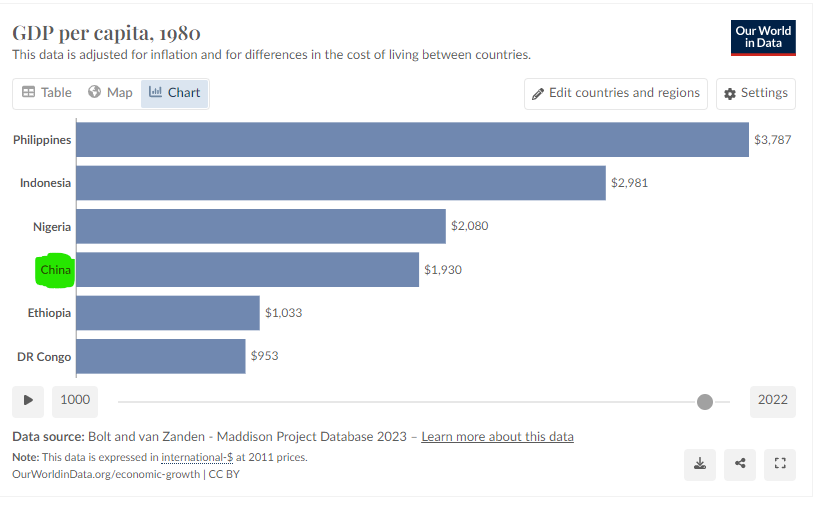

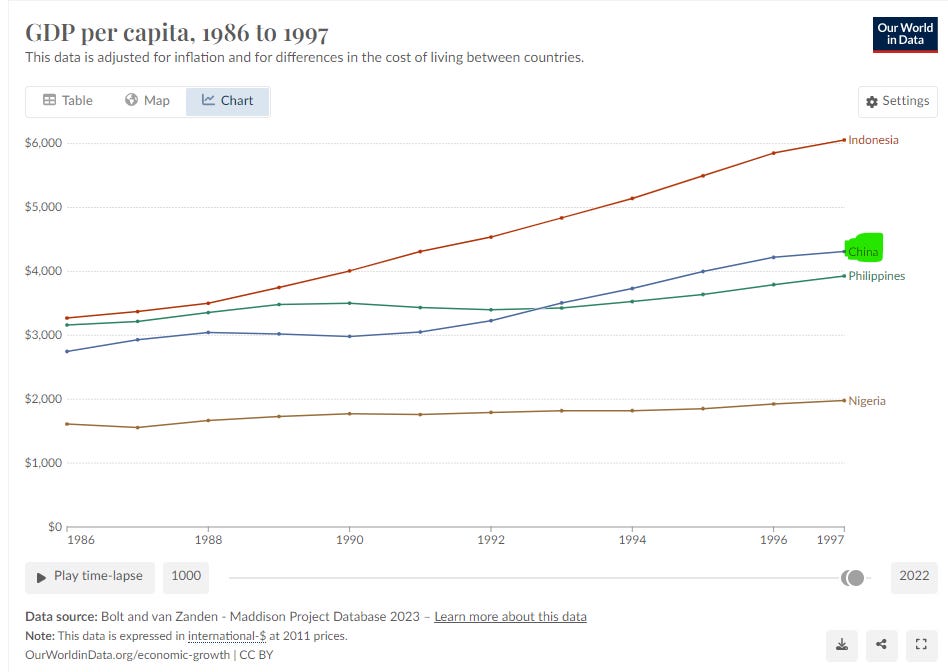

Upon Deng’s rise, he inherited an economy with vast potential but was in shambles. In 1980, China was a low-income country, on par with much of Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. At that time, the average Chinese citizen was poorer than those in Nigeria, Indonesia, or the Philippines. Only a few nations were poorer than China in the 1980s, like the never colonized Ethiopia and the brutally colonized Congo.

In 1980, China joined the IMF and World Bank, showing their willingness to engage with the international financial institutions.

One year later, in 1981, China took its first IMF loan of (450M SDR) which is equivalent to $550M.

China first IMF loan -$550M

When a country borrows from the IMF, it typically does so because the state is locked out of all other financial avenues. Other avenues include:

Raising Taxes: The first option for a government is to raise taxes. However, in poor countries, this is rarely feasible, as the population is often too impoverished to generate significant revenue. The corporations also barely make money or avoid taxes. Finally, if the country tries to implement or increase consumption taxes, it will lead to riots.

Domestic Borrowing: If raising taxes isn’t enough, countries may turn to domestic borrowing. But in many developing nations, local financial institutions lack the financial wherewithal to finance the government’s needs. As a result, domestic borrowing becomes impractical, forcing the country to look outward.

International Borrowing: When domestic sources fail, countries usually try international markets, either by securing syndicated loans from banks like Goldman Sachs/Citi/Standard Chartered Bank or issuing Eurobonds to investment firms denominated in US dollars (misnomer I know). However, if the country is seen as too risky—a financial "basket case"—these institutions won’t lend or the interest rate they ask for is too high, closing off this avenue.

Regional Multilateral Banks: Next, the country might approach regional development banks like the Asian Development Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, or African Development Bank. But these banks typically lend when a country is in reasonably good economic health, as they aim to maintain their strong credit rating. They are unlikely to lend to a country teetering on the edge of bankruptcy, often directing the borrower to seek assistance from the IMF.

Foreign Aid & Bilateral Loans: The country may then ask for aid (grants) or bilateral loans (typically zero interest credit) from wealthier nations. Yet, if the financial situation is dire, Western donors will typically require the country to first approach the IMF before providing additional aid or low-cost loans. The IMF effectively "unlocks" further support from other donors.

Commodity-backed loans from traders: If a country possesses valuable resources like oil fields, bauxite, or copper mines, it can essentially mortgage those assets to secure financing from companies such as Trafigura or Glencore. This practice has been seen in countries like Jamaica, Congo-Brazzaville, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Chad, and more. These loans are often kept “off the books” and only come to light when the country discloses its full loan portfolio during negotiations with the IMF, often in the context of seeking debt forgiveness.

When all other options are exhausted, the country turns to the IMF. Since 1976, IMF loans for low-income countries have been offered at concessional, below-market rates through the IMF Trust Fund program.

At the time, China’s $550M loan was the largest it had ever borrowed internationally. What makes China’s borrowing from the IMF particularly intriguing are two key reasons.

#1 China did not need the IMF loan.

In 1980, China had $10 billion in foreign reserves—more than enough to cover six months of imports, which was well above the three-month safety threshold. In 1980, China imported $20B a year. If we divide $20B by 12 months to find imports per month, that means China imported $1.67B worth a goods per month. The calculation to find import coverage is as follows:

This means when China borrowed from the IMF, it was not facing bankruptcy; it sought the IMF loan as a financial cushion to support Deng Xiaoping's economic reforms. Unlike countries like Sri Lanka or many African nations that borrowed from the IMF out of desperation when they were deep in a ditch, China’s loan was a preemptive, strategic move to manage short-term challenges and push ahead with reforms. Deng was proactive, not reactive—he borrowed as part of a well-calculated strategy.

#2 Deng didn’t care for IMF advice

When countries borrow from the IMF, they typically endure "financial surgery" dictated by IMF advisors—measures like austerity and structural adjustments, often involving definite short-term pain for potential long-term gain.

IMF borrowers typically fall into two categories: the “faithful executors” and the “shoddy executors.”

Faithful Executors: These countries take IMF loans because their governments are desperate, near bankruptcy, and lack direction, essentially outsourcing their economic strategy to the IMF. Argentina in the early 2000s is a prime example. After decades of Peronism — a post-WWII “third way” between American capitalism and Soviet communism that featured strong unions, state-controlled wages, generous public pensions, state owned enterprises, big subsidies for private firms, and high welfare spending that placated the poor, but fueled corruption, economic mismanagement, and a 1982 debt default— the country elected neoliberal Fernando de la Rúa, who faithfully followed IMF reforms. However, the short-term pain was too great for the population, leading to riots, and by December 2001, Argentina defaulted again.

Shoddy Executors: These countries accept IMF loans but misuse them, often embezzling funds or using the money to maintain patronage networks. Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire (now Congo) was a classic "shoddy executor." His implementation of reforms was erratic at best. For instance, when the IMF advised him to shrink the public sector and reduce wage increases, Mobutu kept the bloated bureaucracy intact, simply leaving civil servants unpaid. While the IMF called for a floating currency, Mobutu allowed devaluation but repeatedly re-anchored the currency, undermining the intended reforms. Most notably, he resisted privatizing state-owned enterprises—such as Gécamines (copper & cobalt mining), MIBA (diamond mining), SNEL (electricity), and ONATRA (transport)—which remained hubs of corruption. By 1992, Zaire defaulted on its debt, and the IMF cut ties with Mobutu in 1993, fed up with his empty promises. In a few years, Congolese experienced Holocaust levels of death, where the two Congo Wars erupted from 1996-2003, killing 6M+ Congolese.

Deng Xiaoping: A Third Approach

Deng Xiaoping, however, did a third option—he executed market reforms at his own pace, balancing social stability with economic productivity.

Deng had a framework—his "Reform and Opening Up" (gaige kaifang) framework had been in place since 1978, three years before the loan. He wasn’t seeking IMF guidance; he just wanted the financial buffer. Deng didn’t follow the IMF's aggressive timeline. The IMF pushed for rapid changes in a three to five year time span—such as:

1. Curbing government spending to reduce fiscal deficits

2. Raising interest rates to combat inflation

3. Privatizing loss-making state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to increase efficiency

4. Floating the currency to make the currency more resilient to currency shocks

5. Opening the economy to foreign investment

The IMF’s advice was directionally correct—market reforms were needed—but Deng had already planned many of these reforms without their help. The real question was timing. The IMF pushed for rapid change within 3-5 years, but this was politically incorrect for China’s political elites. Instead of shock therapy, Deng favored gradualism, a process still unfolding today.

Deng’s Pragmatic Reforms

Deng didn’t rigidly follow the IMF neoliberal blueprint. Instead, he approached reform with flexibility, experimenting like a Product Manager refining a prototype. Here’s what he did:

Dissolving farming communes: Land was allocated to households via the Household Responsibility System, though the land remained state-owned.

Reforming Prices: Deng gradually removed most of the 600 price controls on many goods through a dual-track pricing system, where state-controlled prices applied to certain quotas, and market prices applied to excess production.

Creating Special Economic Zones (SEZs) :To attract foreign investment, Deng made SEZs starting in Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shantou, and Xiamen—well before the IMF loan. The SEZs allowed China to experiment with market reforms in designated areas, without overhauling the laws governing the entire economy.

Reforming instead of privatizing State owned enterprises (SOEs). Deng’s approach was focused on granting more autonomy to SOEs and introducing market-oriented reforms. He allowed managers in SOEs to have more decision making in production, pricing, and hiring, rather than the government having strict quotas.

Establishing stock markets in Shenzhen and Shanghai in the 1990s while maintaining strict capital controls that still exist today.

When you consider these nuances, you start to understand that Deng was NOT a free market capitalist; he was a pragmatist, famously saying “I don’t care if the cat is black or white, so long as it catches mice.” Land ownership remained in state hands, and the “commanding heights of the economy” still stayed under government control, following socialist doctrine.

While Deng is often credited for China's reforms, it's important to acknowledge the influence of Chen Yun and other conservative officials who pushed to maintain Maoist traditions. In China, "conservative" means adhering to Mao’s communist principles, while "reformer" refers to the market-oriented approach—a reversal of Western political labels.

Chen Yun, a key figure in China’s state planning system, often tempered Deng’s bold reforms with caution. Known as the “two tigers on the same mountain,” Chen advocated a “look-before-you-leap” approach, in contrast to Deng’s willingness to take risks.

Chen believed that economic reforms should be carefully controlled to preserve social harmony. This was reflected in his "birdcage theory," where the market (the bird) could operate freely, but only within the constraints set by the state (the cage).

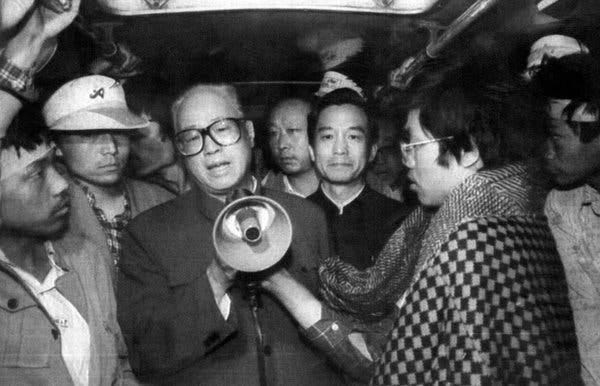

If Deng was the Product Manager, his lieutenants were the engineers executing his vision. Among them was Zhao Ziyang (pronounced "zee-yahng," rhyming with "song"), a staunch advocate of market reforms. Zhao played pivotal roles as Party Secretary of Sichuan (pronounced "See-Juan"), Primer, and eventually General Secretary, pushing forward Deng's reform agenda.

Implementing market reforms didn’t immediately transform China into an economic success. The country faced significant growing pains. By 1986, Chinese incomes had surpassed those in Nigeria, which was in decline, but China still lagged behind developing nations like Indonesia & the Philippines.

Second IMF Loan in 1986

In 1986, Deng recognized the need for further reforms and strategically secured a larger IMF loan of 600 SDR ($765M), though China didn’t need it—reserves had grown to $17B, covering five months of imports, exceeding the 3 month emergency signal.

China was importing more capital goods, equipment and technology to accelerate industrial growth (“importing stuff needed to make more stuff faster”). The IMF pushed for the same reforms—privatizing SOEs, cutting spending, lifting price controls, and floating the currency—but Deng continued to follow his gradual approach towards foreign investment & trade.

Reforms weren’t without challenges. Corruption was notoriously rampant in China. There was significant tax evasion and there were corrupt middlemen & government officials. Deng was worried that the Shenzhen SEZ “could fail”. From 1986 to 1990 and 1992 to 1997, China faced rampant inflation, peaking at nearly 30% in 1989.

Unemployment spiked after 1988 as state-owned enterprises (SOEs) underwent more significant restructuring. Once seen as the "iron rice bowl" offering lifetime employment and social benefits, SOEs were downsized to boost efficiency, leading to job losses. The graph below illustrates the rise in unemployment during this period.

The combination of inflation, rampant corruption, and rising unemployment led many to believe political reform was needed, ultimately sparking the Tiananmen Square Incident.

Deng temporarily slowed down reforms, and had a few years of stagnation dealing with the aftermath of his harsh crackdown. America and the European Union issued sanctions on China (mainly arms embargoes) and made the World Bank stopped issuing loans to China. Japan & America, which both had the most shares in the Asian Development Bank, stopped issuing loans to China as well.

At that point some leaders would have chosen to stop trying to embrace market reforms, but Deng doubled down reforms with his Southern Tour in 1992.

By the time Deng died in 1997, China got even richer. By 1997, the average Chinese was richer than a Filipino and China has not borrowed again from the IMF since 1986.

Today, average Chinese living standards are basically equivalent to Thai people and Mexicans when we adjust for purchasing power and inflation. If we look by province, people who live in Beijing and Shanghai are richer than the average Japanese or South Korean. Meanwhile places like Gansu and Heilongjiang have living standards closer to South Africans or Indonesians.

Concluding Thoughts

Development economics is far more nuanced than "IMF = bad." There's a big difference between taking an IMF loan as a financial cushion for reforms you’ve already planned, like Deng did, versus borrowing out of desperation when you're bankrupt and barely doing reforms like Mobutu did.

What stands out about Deng is his pragmatism. The idea that "America made China rich" overlooks China’s internal dynamics, and thinking "China got rich by adopting capitalism" ignores the elements Deng deliberately delayed. The best way to think of China is that its a “socialist market economy”.

Great work. I also recommend a deep reading of Zhu Rongji. If Deng was the “architect” of gaige kaifang, the Zhu was its true engineer.

Thanks, that’s interesting. S Korea also borrowed from the IMF. I assume they implemented all the IMF reforms and turned out to do OK? That said, perhaps there is a legitimate issue about whether S Korea could have recovered with less pain to its most vulnerable population if they made more gradual reforms.

I think another “model” is Malaysia (where I am at now) which went against IMF and imposed capital controls. I understand even the IMF today acknowledges that Malaysia did the right thing! 😀