The IMF Part 2 - How the fund actually works.

Let's Resolve some misunderstandings

I wrote part 1 about a year ago — click here to check it out.

Founded at the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), headquartered in Washington, D.C., serves as a lender of last resort to 190 countries. With over 2,400 staff, mostly from Western nations, it manages 982 billion SDR ($1.3 trillion) in assets and has a lending capacity of 695 billion SDR ($932 billion) as of December 2023. You can explore the IMF’s simplified balance sheet here.

For those unfamiliar, the SDR (Special Drawing Rights) is essentially the IMF’s currency, which I’ll explain in more detail later.

As of September 2024, $112 billion in IMF loans remain outstanding. Argentina, Egypt, Ukraine, Ecuador, Pakistan, and Angola account for 60% of this debt—Argentina alone owes $31 billion. Below is a list of countries with over $1 billion in IMF debt.

On "Developing Country Twitter," you'll often find memes painting the IMF as evil. Here’s examples:

I have many criticisms of the IMF, but misinformation clouds real critique. Much of this confusion comes from a lack of understanding of international finance concepts, like 'balance of payments,' making informed understanding difficult.

Myths about the IMF

Misunderstanding #1 - IMF Loans are Expensive

Contrary to popular belief, IMF loans are concessional, meaning they come at lower interest rates than those available from commercial banks. While repayment struggles are real, these loans remain more affordable than other financing options.

To grasp why this misconception exists, it's important to understand some basic finance. Poor countries lack domestic savings—the money set aside by households, corporations, and governments. These savings, typically funneled into banks, fuel local investment. For example, when you deposit money into a bank at 5% interest, you're essentially lending it to the bank. In wealthier countries, domestic savings take various forms, including pensions, 401(k)s, corporate profits, government surpluses, and investment funds like insurance or hedge funds.

In wealthier countries like the U.S., governments fund their needs through taxes and local bond markets.

Poor countries, on the other hand, struggling with low tax revenue collection and limited local savings. Their businesses are mainly informal and a plurality/majority of their population are farmers that live from hand-to-mouth. Even when people do save, they often invest in building homes or expand their informal business which escapes the tax base and the banking system. Unregistered firms are hard to tax, and attempts to increase consumption taxes can spark riots.

In many cases, countries rely on state-owned enterprises, especially in resource-rich nations like Nigeria and Angola, where oil revenue substitutes for taxes. However, this revenue is volatile—Nigeria earned over $100B from oil in 2011 but only $50B in 2022. Why? Because oil prices collapsed. Corruption further compounds the issue, as elites often siphon money abroad to buy Swiss mansions, as seen with Congo's Mobutu Sese Seko. When tax revenue and resource income fall short, governments must turn to external borrowing. Due to this, 60% of Sub Saharan Africa’s debt is denominated in foreign currency.

Countries borrow through:

Syndicated Loans: A group of banks (e.g., Citi, Standard Bank, Abu Dhabi Bank) lends to a country. For instance, Kenya’s 2012 loan was 4.75% above the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR).

Eurobonds: Developing nations pitch investors to lend them money, typically in U.S. dollars so the investor avoids currency depreciation risk. Kenya’s 2019 Eurobond had a 7% interest rate for the first $1B tranche and 12% for the second.

Regional Multilateral Banks: These institutions lend more conservatively to preserve their credit rating, like the African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, and more.

Bilateral Loans: Countries can also borrow from national development banks like China’s Development Bank, which offers concessional loans.

If these options aren’t available, countries turn to the IMF. IMF loans, akin to a global credit union, are based on a basket of five currencies (USD, Euro, Pound, Yen, Renminbi), offering concessional rates derived from a 3-month government bond weight average. China joined the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR) in 2016, and as of Sept 2024, the IMF’s base rate is around 4%, much lower than market rates. This makes IMF loans more favorable compared to commercial loans. Ultimately, the IMF SDR rate is low because its based on government bonds from stable, low-risk economies.

Naturally, America has the highest weight. You can look up the basket weights here.

Since 1992, the SDR hasn’t even hit 6%.

The IMF offers two main types of loans: the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) and the Stand-By Arrangement (SBA). Both start at the SDR rate, but an additional 2-3% is added if a country borrows beyond its quota or holds the loan for over three years.

For low-income countries, the IMF provides zero- or near-zero interest loans. In 1986, the Structural Adjustment Facility (SAF) and later the Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility (ESAF) in 1987 offered loans at a 0.5% interest rate with grace periods of 5.5 years and 10-year repayment terms. These loans came with conditions, such as controlling inflation, privatizing state-owned firms, cutting subsidies, and reducing government spending.

However, the impact varied. Countries like Tanzania, Kenya, and Ivory Coast saw decreases in per capita education spending, while Ethiopia, Bangladesh, and Mozambique saw increases. Health spending in Zambia, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe also fell sharply under these programs.

By 1999, the Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility (ESAF) was discontinued after criticism for being too harsh, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, where health and education spending often dropped. It was replaced by the Poverty Reduction & Growth Facility (PRGF), which kept the 0.5% interest rate but placed more emphasis on social spending.

In 2005, the PRGF was replaced by the Exogenous Shocks Facility (ESF), offering concessional assistance for countries hit by external shocks, also at 0.5% interest with a 10-year maturity.

Since 2010, the Poverty Reduction & Growth Trust has provided zero-interest loans under the Extended Credit Facility and Rapid Credit Facility. These loans target low-income countries, defined as those with an average income below $1,145 USD for 2024-2025. Currently, 26 such countries remain: 1 in South Asia, 22 in Sub-Saharan Africa, 1 in East Asia, and 2 in the Middle East.

Syria, Yemen, and Sudan used to be lower-middle income countries but the Arab Spring and subsequent civil wars devastated their economies. Sudan, in particular, struggled after losing much of its oil revenue following South Sudan's secession.

In short, countries default on private loans, not IMF loans, because they lack sufficient tax revenue or domestic savings to borrow locally. When countries are in crisis, regional banks avoid lending to protect their credit ratings. IMF loans offer a lifeline with lower interest rates than commercial financing, especially for low-income nations, which pay little to no interest. The challenge with IMF loans lies not in the rates but in the austerity measures that often accompany them, sometimes leading to economic stagnation.

Misunderstanding #2 - IMF causes poverty

A common critique is that the IMF causes poverty, but in reality, it acts more like a financial firefighter—stepping in to stabilize crises, not create them. Its tools can be blunt, but the IMF typically steps in when countries are already bankrupt and locked out of global markets, turning to the IMF as a last resort.

Many struggling countries follow a familiar pattern that eventually leads them to the IMF. Let me explain.

First, developing nations often anchor their currency to the dollar to make essential imports like food, fuel, and manufactured goods relatively cheap. By doing so, the central bank artificially boosts the nation’s living standards. For instance, consider Sri Lanka.

Second, these countries run persistent current account deficits, meaning they import more than they export. This creates constant downward pressure on their currency.

If you peg your currency to the dollar while running current account deficits, you're effectively propping up your currency artificially. Deficits, by definition, create more demand for the dollar than for the local currency, which should push the local currency's value down. If the central bank maintains this fixed exchange rate, it is selling dollars and buying back its currency to keep the local currency stable.

Third, central banks may claim to have a floating exchange rate, even when they are heavily intervening. Sri Lanka’s central bank, for example, maintained that it had a floating regime (currency’s value is based on free markets, no intervention) while defending the rupee through interventions—essentially a misrepresentation of its true policy:

Why do central banks obfuscate this? There are a few reasons:

Projecting confidence: Countries with floating regimes, like the U.S. or Canada, signal to markets that their economies are strong and self-sustaining. Sri Lanka admitting to a currency peg/managed peg could reveal vulnerability, suggesting the nation may one day lack the reserves to maintain it.

Avoiding speculative attacks: If hedge funds know a country is defending its currency, they might try to "break the peg" by short selling the currency, profiting from the country’s struggle. Some central banks hope that claiming a floating regime will deter speculators, though savvy investors often see through this.

Accessing IMF funds: The IMF encourages floating exchange rates, and failure to meet this expectation can limit the financial assistance a country receives.

Fourth, the country borrows heavily in foreign currency to compensate for insufficient domestic savings.

In Sri Lanka’s case, foreign debt rose from 37% to 81% of national income in just 12 years. By 2020, the country was spending 71% of government revenue on interest payments—more than it spent on health and education combined.

As reserves dwindle from efforts to maintain the currency peg and as borrowing escalates, local investors start losing confidence. Fifthly, investors convert their rupees into dollars or sell off rupee-denominated assets—this is capital flight. As a result, Sri Lanka’s foreign reserves dropped from $10 billion in 2018 to under $2 billion by 2022.

You might wonder, "But they still had $2 billion—why did Sri Lanka have issues?" The problem is that $2 billion wasn't enough to cover even one month's worth of imports. A healthy reserve should cover at least three months of imports. By late 2021, Sri Lanka was well below this threshold, signaling a looming crisis.

When capital flight occurs and foreign reserves dry up, the country can no longer finance imports or service its debt. Eventually, the dam breaks, and the costs of essentials like food and fuel skyrocket.

By April 2022, Sri Lanka defaulted on its debt. Now let’s stop looking at numbers and see what this looks like for normal people. See the image below:

This brings us to the real misunderstanding: The IMF doesn't cause these crises—countries come to the IMF after years of mismanagement. The IMF steps in to stabilize the situation, but its austerity measures—like cutting public spending and subsidies—could slow recovery and create hardship for everyday citizens. But the measures are needed to restore investor confidence in the country. Normal People might not understand concepts like hedge fund speculation or current account deficits, so they see the IMF as the source of the crisis rather than a responder.

In fact, some countries even worse off than Sri Lanka face additional problems, like unprofitable state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that serve more as “employment absorbers” to prevent mass unemployment rather than be viable businesses. Governments also enforce price controls on essential goods like food or electricity, keeping prices low through subsidies that require even more borrowing. This borrowing, however, doesn't go toward investments that grow the economy—it funds consumption.

You may think, "But America has massive debt and runs current account deficits too!" That’s true, but there’s a crucial difference: the U.S. has a floating currency, and all its debt is in dollars. There’s no "dam" to break because the U.S. doesn't have to defend a fixed exchange rate, and interest payments take up only 19% of government revenue as of 2024.

Other examples besides Sri Lanka

In the 1970s and 1980s, many developing countries, including several in Africa, borrowed heavily in an attempt to rapidly industrialize. This binge led to debt crises across the developing world. Africa’s debt crisis was from 1980-2000. Latin America had its debt crisis from 1982 to 1989, while South Asia (Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and India) faced crises in the 1980s and early 1990s. East Asia suffered from the 1997-1998 Asian Financial Crisis, during which countries like South Korea, Thailand, and Indonesia faced massive capital outflows. IMF and other institutions provided $118B and told the countries to raise taxes, cut spending, and eliminate subsidies.

Misunderstanding #3 - IMF steals resources

The IMF doesn’t take resources—this confusion often stems from mixing up the IMF with commodity traders like Trafigura or Gunvor, who are involved in resource extraction deals. If you're curious about these companies, I've written more about them (here, here, & here).

Misunderstanding #4 - The IMF Creates “Debt Traps”

You can “get out” of debt traps by increasing domestic savings.

Some critics accuse the IMF of creating “debt traps,” but the real issue is often a lack of domestic savings. For instance, Tanzania avoided IMF loans after 2012 by increasing its savings rate from 23% to 37% of gross income($8.5B to $29B), even though Tanzanians earn half as much as Kenyans who have much lower domestic savings.

India, Vietnam, and the Philippines also stopped IMF borrowing long ago.

How a Country Messes itself

The so-called “debt trap” isn’t an IMF conspiracy—it’s driven by governments that continue mathematically innumerate practices, knowing they can rely on cheap IMF loans. Unproductive political patronage further compound the issue.

Every country has unproductive patronage, the questions are “How much?” & “At what scale?” Part of the reason why California can’t solve homelessness is because it outsources capacity to unactionable non-profits. But they get money because they are large supporters of California municipal and city governments.

In developing countries, the political patronage is magnified. The patronage systems worsen the situation, as political elites prioritize interest groups over the general population—military spending placates the army to prevent coups, and expensive food/fuel subsidies and low electricity tariffs stop the urban middle class from rioting. Other patrons can include business elites, religious figures, tribal chiefs, domestic intelligence agencies, ethnic/tribal warlords who cause mayhem unless he’s paid, some Swiss commodity trading firm who provides support to sell the country’s commodities, or patronizing other countries to curb refugee flows or keep a weaker country aligned on foreign policy.

Below is my simplified diagram illustrating the domestic patronage network of former Sudanese President Omar Al-Bashir.

The IMF isn’t deliberately "trapping" countries in debt. Rather, it’s often the country’s own elites who, in trying to maintain power and placate key domestic patrons, inadvertently lead their nation into unsustainable debt. The solution isn’t as simple as ending corruption—an impossible task in any country—but rather aligning the interests of the patronage networks with economic policies that promote stability and growth. This way, they can avoid having to return to the IMF for help.

The real challenge, and the million-dollar question, is how to achieve this alignment. There’s no one-size-fits-all answer, as each country’s political dynamics and patronage systems are unique.

IMF has done Debt Forgiveness Twice

Another often-overlooked point that weakens the "debt trap" argument is the IMF’s large-scale debt relief efforts, starting in the late 1990s with the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (HIPC).

NGOs, faith-based institutions, and the global public — especially through the Jubilee 2000 campaign — lobbied for global debt relief. The result was the cancellation of $100B owed to 35 of the world’s poorest countries.

While the debt relief brought temporary relief and made Westerners feel good, it didn’t address the deeper issues. Clearing a country's debt doesn’t solve the underlying structural problems of low domestic savings and entrenched political patronage that continue to hinder economic progress.

Ethiopia’s story illustrates this. if you look at the chart below, in the late 90s, Ethiopia owed $10B mainly denominated in foreign currency that was larger than its GDP. Russia and the IMF forgave most of Ethiopia’s debt bringing it down to a low of $2.2B by 2006. However, Ethiopia still needs new highways, needs to fund new programs, and subsidize new state owned enterprises. Ethiopia went on an incredible borrowing binge from both China and international markets and quickly surpassed its previous 1990s all time highs in 6 years by 2012. Unfortunately, by Dec 26th 2023, Ethiopia defaulted on its debt again. See the chart below:

This pattern of debt accumulation, relief, accumulation, and default repeats across many developing nations, including Ghana and Mali.

Debt relief for Ethiopia was still beneficial, as it allowed the government to prioritize its people over paying interest to creditors. However, if a country remains poor, struggles to collect tax revenue, and lacks domestic savings (with few banks, pension funds, or insurance companies to buy government bonds), it will inevitably turn to international lenders again. It's no surprise that Ethiopia quickly borrowed more, surpassing its previous debt levels.

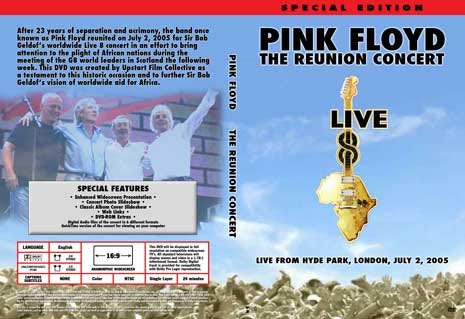

Then in 2005, due to continued pressure from institutions like Live 8 concerts and Make Poverty History, there was considered pressure for another IMF debt relief initiative.

The Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative, launched by institutions like the IMF, World Bank, and African Development Bank in the 2010s, aimed to provide further debt relief. Liberia, for example, saw its debt reduced from $4.2 billion in 2006 to just $420 million by 2010—a 90% reduction. Similarly, Togo’s debt dropped from $2 billion in 2007 to $600 million by 2011.

However, debt relief alone doesn’t prevent countries from accumulating debt again. Togo’s debt has since risen to over $3 billion, with its debt-to-income ratio now higher than it was in 2008.

Concluding Thoughts

Development is complex—it demands a grasp of history, international finance, economics, patronage systems, and human behavior.

Balancing these ideas simultaneously is tough, which is why many people gravitate towards low resolution solutions such as “we are poor because IMF traps us”, “We need Reparatory debt relief”, or “Just end corruption!”

The countries that succeed are led by those who can navigate these complexities. That’s why Deng Xiaoping stands out as one of the greatest leaders of the 20th century. He ousted the Gang of Four, aligned the military, delivered rapid results, and doubled down on market reforms even during intense protests.

Next time, I’ll critique the IMF’s conditionality, its limited grasp of political patronage, its role as a U.S. foreign policy tool, and examples of disastrous IMF advice, like in Russia.

Excellent piece. One additional thing that isn't touched on much however is the real role of SAPs; these make a good deal more sense once you stop viewing them as external constraints for accessing funding, and instead see them as accountability sinks to enable the introduction of necessary but unpopular reforms. As you rightfully point out, because of these various poor quality governing practices, many developing economies end up in unsustainable situations for which the only way out is fairly painful austerity. This is usually very politically difficult to implement, to the point that any domestic government that tries is likely to face serious pressure (see ongoing protests surrounding Ruto). The role of the IMF in this situation is to essentially absorb the negative sentiment such reforms create - domestic leaders can point to the deficits and declare that they have no choice but to implement the reforms or else they will default on debt. Then, when popular sentiment turned bad, it allows them to turn around and point to an external bogeyman in the form of the IMF to blame it on. A common phrase in management cybernetics is ‘The Purpose of a System is What It Does (POSIWID) - in this case, what the IMF does is provide a relatively politically painless way for leaders to implement austerity reforms.

As a way of operating, I have mixed feelings about this. On the one hand, it’s a very effective accountability sink - those responsible for determining the reforms are sufficiently removed from those responsible for implementing them that it can very effectively protect the process of decision-making. On the flip side however, this distance between the IMF and country in question undermines the informational flow between them, as as an external body the IMF is likely to have a worse grasp on the situation, and thus promote worse proposals, than an actual on-the-ground governmental institution. Because of this, my personal preference in these situations is to instead find a way to sell the necessary reforms directly to the people - this is difficult but not impossible, as Milei in Argentina has shown.

Great article as always.

I do have a little doubt about this :

"What actually happens is that when the IMF advises a country to let its currency "float" (allowing its value to be set by market forces), the currency often depreciates. For countries that rely on exporting commodities like tea (Kenya), vanilla (Madagascar), or copper (Zambia), this makes their goods cheaper for foreign buyers."

Most of those commodities are priced and traded in USD. Why would Zambia's copper selling price in USD change because of a depreciation of the Kwacha ?