Guns, Germs, and Cobalt Q&A #8: Global Bilateral Debt, Currency Swaps, Eurozone Crisis Teaser, and German Growth in the 2000s

Debt explanation, Eurozone Crisis Article Teaser, and German Recovery

Time for another Q&A! If you are a new subscriber, read the other parts below if interested: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, and Part 7

#1 Bilateral Debt: Which Governments are the Largest Lenders?

The 2024 International Debt Report highlighted key insights on bilateral lending, where one government lends directly to another government. This contrasts with multilateral lending, which involves many governments in institutions like the IMF, World Bank, or regional development banks (e.g., Asian, Inter-American, or African Development Banks).

The top bilateral lenders to low, middle, and upper-middle-income countries are China, Japan, France, Russia, Germany, Saudi Arabia, and India.

The U.S., by contrast, focuses on multilateral lending as a top donor to institutions like the IMF, World Bank, and various regional development banks (Caribbean, European, Asian, African, and Inter-American).

The $250B+ lenders

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has made it the largest bilateral lender, with $267 billion owed by borrowing countries. However, poor loan performance, particularly in Africa, has led China to write off some debts. Japan, a big bilateral lender since the post-WWII era, has its own initiative, the Free & Open Indo-Pacific, to compete with China.

China has lent to over 75 non-high-income countries, while Japan’s reach extends to about 55 countries.

#2 What are currency swaps & Who uses them?

A bilateral currency swap line (BSCL) is an agreement between two central banks to exchange currencies, allowing one to access the other’s currency for foreign exchange needs and trade.

The main purposes of a BSCL are to:

Stabilize a currency (maintain a currency’s anchor to another currency).

Provide liquidity during crises (having the right amount of cash at the right time, quickly)

Promote the international use of a currency (e.g., the Chinese renminbi).

Currencies like the U.S. dollar, Japanese yen, the euro and British pound usually do not require such swaps due to their internationalized status. Currently, China has 40 currency swap agreements totaling 4.2 trillion yuan ($590B) with partners like the European Central Bank, Hong Kong’s Monetary Authority, and Sri Lanka.

In July 2024, Ethiopia, facing a foreign currency shortage, entered a 3 billion dirham ($817M) currency swap with the UAE, enabling Ethiopia to import oil, iron, and steel directly in dirhams, reducing reliance on dollars.

In a currency swap, the UAE's central bank and Ethiopia's central bank agree to exchange 3 billion dirhams for an equivalent amount of Ethiopian birr at a set exchange rate. Ethiopia holds the dirhams to pay UAE exporters directly in their local currency, bypassing the need for scarce foreign currencies like U.S. dollars or euros. After the swap period, both central banks return the original amounts or extend the agreement.

Also, UAE gets Ethiopian birr, Emirati firms in Ethiopia can conduct transactions in the local currency without converting to dollars.

For Ethiopia, the swap addresses its shortage of foreign currencies like dollars, pounds, and euros, enabling trade with the UAE using dirhams. For the UAE, it promotes the international use of its currency, reducing reliance on the dollar and boosting its role in global trade.

#3 Why Don’t all countries do currency swaps?

Not all countries engage in currency swaps because these agreements depend on economic needs and strategic interests.

Market participants generally like international currencies. Most countries don’t mind using the dollar, or to a lower extent the euro/yen/British pound. The Bank of International Settlements has data that the dollar. The US dollar was involved in 90% of global foreign exchange transactions.

Need Trade Ties: Countries need to engage in significant trade to justify currency swaps. For example, Nigeria has a $2B currency swap with China. However, it doesn’t have one with Ghana. Why? Let’s look at data. Officially, Nigerians sell $173M to Ghanaians while Nigeria sells $1.52B to China.

Don’t trust the currency: Very few countries want to do a currency swap with a country they don’t trust economiaclly. Especially if its prone to currency devaluation, hyperinflation, or if the country has chronic current account deficits. Over the past 5 years, the Congolese franc has lost 50% of its value to the dollar.

#4 How Bad was the Eurozone Debt Crisis? (Teaser Article)

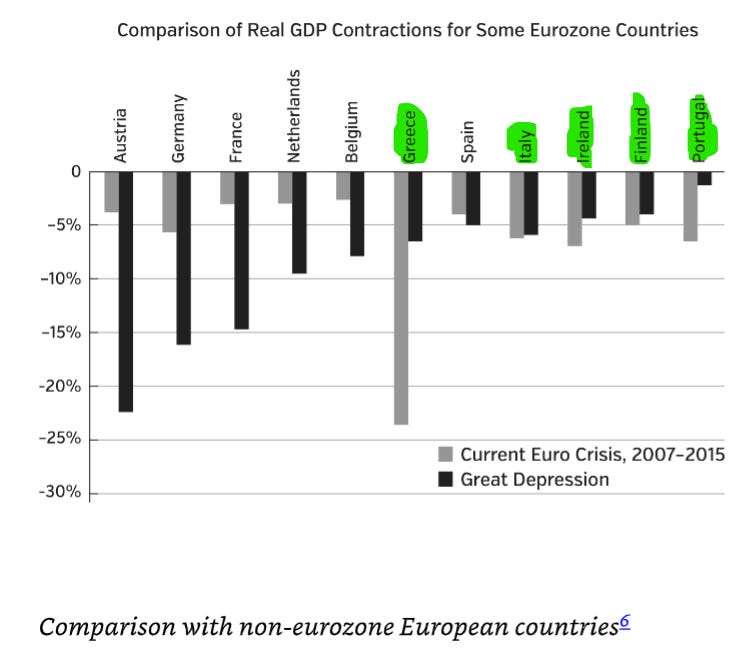

The Eurozone Crisis, born from the U.S. Great Financial Crisis, swept across Europe like a tsunami. Countries like Germany and France treaded water in an exhausted state, while Italy, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain drowned. Greece’s body was not found after drowning. For the GIIPS (Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Spain) nations and others, it was worse than the Great Depression. It was a dark chapter for the region, exposing deep cracks in the Euro's foundation. See the comparison below for how bad this crisis was compared to the the Global Great Depression of the 1930s.

Background:

By 2002, euro banknotes and coins were introduced, and by March, national currencies were no longer legal tender. No French or Belgian francs, no Italian Lira, and no Spanish Peseta. Member nations gave up monetary sovereignty, handing control over money supply and interest rates to the European Central Bank (ECB), while retaining control of fiscal policies like taxation and spending.

The GIIPS nations (Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, & Spain)

For the GIIPS nations, the euro was transformative. Previously, these countries faced high borrowing costs due to fiscal instability—Greece's borrowing rates reached 18% after its 1980s debt binge. Joining the eurozone slashed borrowing costs to near-German levels, as Greece received a massive boost on its investment credit rating. Investors assumed eliminating exchange rate risk meant Greece couldn’t devalue its currency, as it had in the 1970s and 1980s, which wiped out investor returns (Investors were right on this). However, investors also believed that France or Germany would bail out Greece if trouble arose (Investors were wrong on this… cue Former German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble and Former Chancellor Angela Merkel's laughter).

Relatively poorer countries like Greece, Cyprus, Portugal, and Spain borrowed at unprecedentedly low rates after joining the euro. They spent heavily on infrastructure and pensions, financed by deficit spending through bonds. Bonds work by paying interest over time and repaying the principal at the maturity date. These countries issued new bonds to repay old ones, perpetuating debt in a process called "rolling over debt”— a common practice, but these GIIPS & Cyprus stood out for their high debt and low productivity. This cycle enabled Greece, for instance, to spend $12 billion on the 2004 Athens Olympics.

In 2006, cheap bonds fueled a massive housing bubble in Spain, leading to more homes being built than in France, Germany, and Ireland combined. The issue is construction isn’t a tradable sector like making cars, computer chips, or pharmaceutical drugs. Its not as productive as a sector for long term growth. Real Estate has bubbles… which popped…

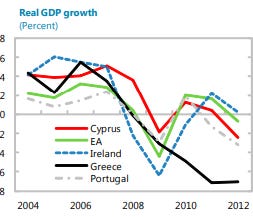

Fueled by government jobs, tourism, construction, & real estate, the poorer European countries (GIIPS) experienced convergence growth, catching up with richer nations like Austria, Germany, and Belgium. However, by the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, growth collapsed. Cyprus, Ireland, and Portugal faced sharp declines, while Greece fell into economic ruin. See the Real GDP growth chart below for details.

Issues with the Euro:

The European Central Bank (ECB) manages interest rates, which impacts the euro's value:

Lowering rates weakens the euro, making investors sell it for stronger currencies.

Raising rates strengthens the euro, attracting investors seeking higher-yield euro-denominated bonds.

Individual eurozone countries can’t devalue their currency to boost exports during a recession, as they don’t control the euro. The ECB could intervene in currency markets but prefers market-driven mechanisms. It could theoretically print euros (electronically create euros) to buy dollars/yen from currency market participants to weaken the euro and strengthen the dollar/yen. This would artificially boost GIIPS exports by making their goods artificially cheaper to undercut global competition. However, the ECB's mandate for price stability (low inflation) prevented this, as devaluing the euro would raise import costs, like fuel. Besides, Greece’s main “exports” were tourism and shipping, not goods that could easily benefit from a weaker currency.

Loss of Competitiveness:

The GIIPS nations were weaker economies compared to France, Germany, or Austria. When the GIIPS had their own currencies (e.g., lira, drachma, peseta) in a recession, they could devalue them to make exports cheaper and boost competitiveness, as countries like China and Japan have done.

Joining the euro stripped them of this control, making their currencies artificially strong. While a strong currency lowered inflation and made imports cheaper, it hurt their ability to compete internationally.

The Problem with a Shared Currency:

Sharing the euro means countries lose control over interest and exchange rates, despite differing economic needs.

For example, when a country loses monetary sovereignty, the following happens:

Overvalued currencies in trade deficit nations can’t devalue to boost exports.

Countries with undervalued currencies and large surpluses can’t overvalue to make imports cheaper

During America’s financial crisis, it spent its way out of a recession. However, Germany & France did not want to bailout Greece for reckless borrowing, especially since Greece also lied about its finances.

Instead, the GIIPS countries relied on internal devaluation—reducing wages and prices through austerity. If you weaken aggregate demand, then there will be more downward pressure is put on prices. In layman’s speak, if you cannot change interest rates or your control currencies’ value, you should probably induce mass unemployment in your country get in a reset. You cannot expect Greek people to export shoes and compete with China or Vietnam. Greece needed to stop protecting its industries, stop having a bloated civil service, and let workers find more productive work. This involved cutting government spending, weakening labor markets, killing pensions, and inducing unemployment to lower wages and help Greece firms export more on the global market. Reduced wages also limit imports, as people can no longer afford them.

If you think that sounds evil to purposely make your people go unemployed just to fix some structural instability in your economy, you would have a point, but unfortunately that’s what Europe did. This approach, while "logical" in economic terms, has devastating human costs: lost jobs, lower living standards, and long-term harm to society. During the Eurozone crisis, ECB head Claude Trichet suggested faster wage cuts through weakened unions, believing this would speed recovery. Instead, these policies prolonged economic stagnation, causing immense suffering across the GIIPS nations. This internal devaluation led to a slog of GDP.

Note: This is just a “teaser” article of the Eurozone Debt Crisis. I still have to talk about Greek Corruption, Greece’s three Troika bailout programs, Ireland’s & Spain’s housing bubble, Cypriot bank deposit confiscation “bail in”, cultural differences between European countries, and more.

#5 How Did German Industry stay competitive in the 2000s?

Germany initially had sluggish growth after reunification in 1990.

From 1991 to 1998, German growth was pretty awful in real (inflation-adjusted) prices at purchasing power parity, German wasn’t even growing at 1% a year compared to other European countries:

In the 1990s, Germany was the “Sick Man of Europe”. In the early 2000s, Germany also had a “Dot Com Bubble”, 96% of the German tech stock market value dropped. Unemployment was 13.4%. Also, Germany was not the trade surplus “powerhouse” yet, it was like most advanced countries and ran trade deficits.

At the time, the German Center-Left Social Democratic Party, run by Gerhard Schröder executed the “Hartz reforms”.

This was basically an “internal devaluation” to boost competitiveness.

Labor Market Flexibility: The government encouraged temporary employment by deregulating temp work agencies, making it easy for firms to hire and fire. There was improved job placement services to help people find jobs.

Gig Work: Germany introduced low wage, part time jobs with earnings capped at €400 (later €450). These jobs were exempt from income tax and social security contributions, encouraging employers to hire part-time workers.

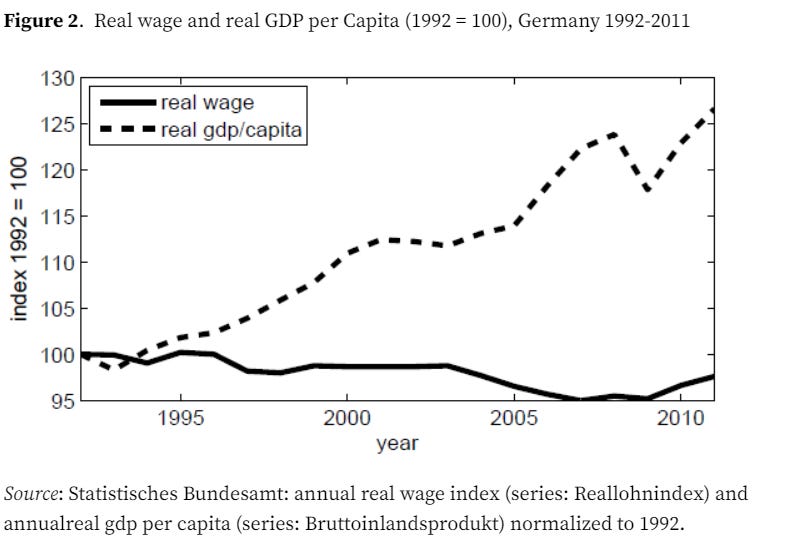

Unions Suppressing Wage Growth: Mitbestimmung (Co-Determination). is a German system of workplace government that gives workers a formal role in decision making at big firms through workplace councils. Working with unions and employers, the councils co-decide on decisions like work hours, overtime, and vacation. Germany’s powerful unions (especially in manufacturing) agreed to limit wage increases to help businesses reduce the growth of labor costs, which boosted competitiveness in global markets. Look at the graph below, during this period, inflation adjusted wages went down while GDP per capita went up:

This internal devaluation, was exactly what business needed to thrive again. Automotive firms (Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz, BMW), machinery (Siemens, Thyssenkrupp), and Chemicals (BASF, Bayer, and Henkel) were able to dominate in the 2000s.

This “internal devaluation” (plus cheap Russian gas and cheap Eastern European labor from Poland/Hungary/Romania) helped Germany export more than import, becoming a trade surplus nation. Also Germany’s growth almost doubled from nearly being 1% a year to almost 2% a year (inflation adjusted). Germany grew faster than Denmark, despite Germany having nearly 15x Denmark’s population.

Frankly, Germany could have taken a more direct role in bailing out weaker eurozone countries, but chose not to.

# Germany's Decade of Policy Failures: From Role Model to Cautionary Tale

During the 2010s, Germany was widely regarded as a global role model—a beacon of pragmatic governance led by Angela Merkel, representing a serious and methodical approach to national management. Fast forward to 2024, and that reputation has dramatically unraveled.

## Strategic Misjudgments

Several of Merkel's signature policies now appear profoundly misguided:

1. **Energy Policy Disaster**: Shutting down nuclear power plants was a monumental error. Ironically, this decision has paradoxically made much of the world suddenly pro-nuclear, exposing the shortsightedness of Germany's energy strategy.

2. **Russian Dependency**: Despite Russia's 2014 Ukrainian incursion, Germany continued placating Putin, most egregiously through the Nordstream 2 pipeline. This geopolitical naivety created a dangerous energy vulnerability.

3. **Refugee Management**: The wholesale acceptance of Syrian refugees has been widely considered a catastrophic miscalculation, with significant societal and economic repercussions.

## Economic Mismanagement

Germany's economic strategies reveal a pattern of systemic short-sightedness:

- Implementing austerity during recession

- Neglecting capital investment while maintaining low debt

- Failing to modernize labor regulations

- Stifling technological innovation through bureaucratic hurdles

## Tech and Innovation Stagnation

The country's inability to digitize effectively has birthed the sardonic "Germans can't code" meme. Both public and private sectors have spectacularly failed to adopt modern software practices. The suggested remedy? Hire talent from Poland and Estonia.

## Renewable Energy: Ambition vs Reality

Germany's renewable energy transition epitomizes good intentions undermined by poor execution. While ambitious, the strategy resulted in solar panel and EV manufacturing shifting to China, trapped by NIMBY permitting rules. Only recently, facing the gas crisis, has some much-needed deregulation occurred.

## The Merkel Legacy

Perhaps most damning is how Merkel left office bathed in undeserved positive sentiment, having effectively planted multiple policy time bombs for her successors. The ultimate irony? Her party might well return to power in the next election.

To truly recover, they would need to comprehensively disavow Merkel's entire policy framework—a tall order for a political establishment deeply invested in her legacy.

*A cautionary tale of how pragmatism without vision can lead a once-admired nation astray.*