The Economic & Geopolitical History of Rwanda Part 1: How Colonialists turned a Caste System into a Race

A tale of a King who sold his sovereignty to avoid a coup

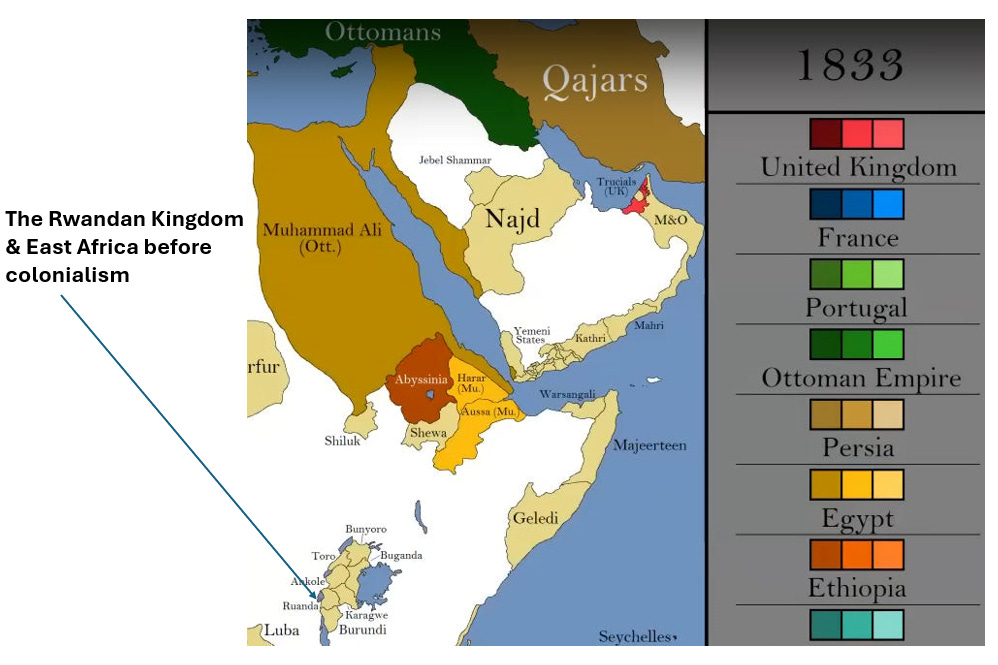

Nestled in the heart of Central-East Africa, Rwanda is a small yet densely populated country with 14.4 million people as of 2024, roughly the size of Maryland or North Macedonia. Rwanda stands out as one of the few African nations whose modern borders closely mirror its traditional kingdom.

Being landlocked in East Africa, Rwanda avoided the horrors of the European transatlantic slave trade, much like its neighbors Burundi and Uganda. Its capital is Kigali, and Banyarwanda make up over 99% of the population and share a single language, Kinyarwanda. However, beneath this apparent unity lies a complex past. A traditional caste system, where Tutsi were cattle owners and Hutu were farmers, was racialized during Belgian rule, transforming socioeconomic divisions into rigid ethnic tribes.

Rwanda: Hype or Miracle?

Since 1994, Paul Kagame has led Rwanda’s recovery from genocide, boosting life expectancy, education, and economic growth, earning it the nickname “Singapore of Africa.” But is this reputation deserved?

A more fitting “Singapore of Africa” would be Mauritius, with a life expectancy of 74, a per capita income of $11,500, and a upper-middle-income status nearing high income. Mauritius is also renowned as an "African tax haven" for high-net-worth individuals. In contrast, Rwanda remains a low income country nearing graduation to lower-middle-income status — a milestone already achieved by half of Sub-Saharan Africa.

While Rwanda excels in some areas, it remains far poorer than Singapore at a comparable stage of development. Singapore’s transformation from poverty to East Asia’s wealthiest nation involved averaging 10% annual growth in the 1960s, with per capita income rising from $472 in 1962 to $1,264 by 1972. Rwanda, by contrast, has averaged 4% annual growth over the past decade, increasing per capita income from $704 in 2013 to $1,000 in 2023. Rwanda’s per capita income also lags behind its neighbors like Uganda and Tanzania. See table below for Rwanda's strengths and weaknesses compared to its neighbors and the continent:

Rwanda’s Contribution to the World Economy

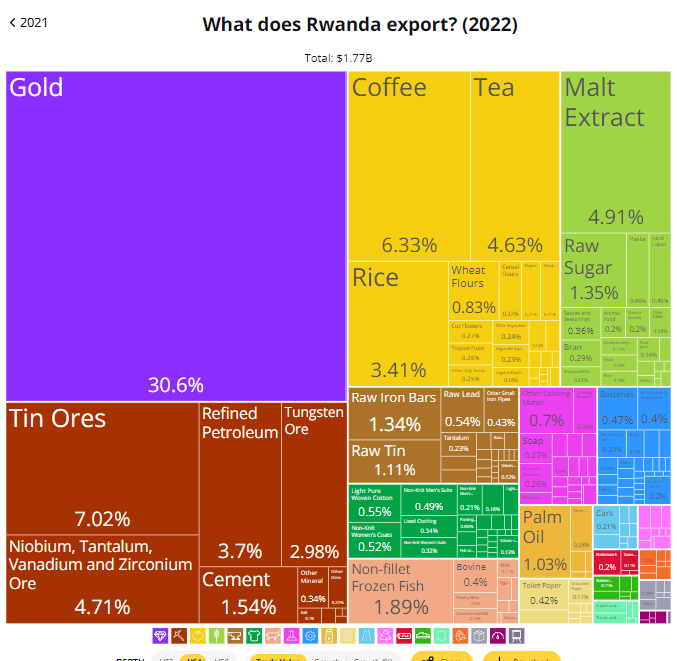

For much of its history, Rwanda's economy was based on peasant subsistence farming, with cattle symbolizing wealth (Tutsi status). Under German rule, the Rwandan king was used to enforce the export of hides, skins, and livestock. After World War I, Belgium took over and introduced cash crops, forcing Rwandans to meet export quotas for coffee beans and tea leaves, which remained Rwanda's main exports until 2001.

In the early 2000s, during the Second Congo War, Rwanda's main exports from its trade statistics shifted to minerals like niobium (used for aerospace alloys), tantalum (coltan, for electronics), tin, tungsten, and zirconium ore (for nuclear reactors). However, most of these resources were re-exported or smuggled from Rwanda’s neighbor, the Democratic Republic of Congo. From 2016 onward, Rwanda's primary export shifted to Congolese gold. See Rwanda’s latest export portfolio below:

Rwanda does not possess significant gold reserves nor does it produce much gold. The gold originates from Congo, with much of it smuggled into neighboring countries such as Rwanda and Uganda.

Beyond gold exports, Rwanda earns nearly half a billion dollars from tourism during peak years.

Agriculture:

Rwanda's farming yields are a mixed bag. Staple crops like wheat, potatoes, sorghum, and corn struggle at subsistence levels, but Rwanda’s rice yields stand out, surpassing much of Sub-Saharan Africa and even rice-heavy countries like Cambodia, Pakistan, and Myanmar.

Pre-Colonial History of the Rwandan Kingdom

The earliest known settlers of Rwanda are the Twa, a pygmy hunter-gatherer community known for their short stature, averaging around 5 feet (1.5m), and their rainforest dwellings.

Between 1000 and 1500 AD, Bantu-speaking people, now called the Banyarwanda, settled in the land and laid the foundation for the Kingdom of Rwanda, an oral society where storytelling, epic poems, and songs preserved history and culture. The concept of ibitekerezo (ideas) was central to teaching wisdom, while imigani (folk tales) imparted moral lessons. According to folklore, the kingdom was founded by the legendary Gihanga of the Abanyiginya clan. The King of Rwanda, was always an abanyiginya Tutsi.

Rwandan Social Structure

Before Belgian colonial rule redefined Hutu and Tutsi as ethnicities, the closest thing to ethnicity was ubwoko which meant clan. There were 15-20 clans such as the Abasinga, Abacyaba, and Abashingo.

In Rwanda, cattle were a sign of wealth because they were portable, reproductive “assets”. They provided milk, hides, manure for farming, and were central to rituals and inkwano (a dowry - the groom’s family offers cattle to the bride’s family as a gift).

Tutsi and Hutu were traditionally castes, not ethnic-tribes. Tutsi were cattle herders, forming the aristocracy, while Hutu were primarily farmers.

A Hutu could become Tutsi through acquiring cows (kwihutura - “to shed Hutu status”), while a Tutsi could lose status and become Hutu through poverty or cattle diseases killing their cows (guhutura - “To fall into Hutu status”). There was also intermarriage between the classes.

The Tutsi made up 15% of the population, while Hutu made up the rest, while the Twa lived in forests.

Kingdom Governance

The kingdom was ruled by the Mwami (Tutsi king), a political and spiritual leader, with the support of:

Umugabekazi (Queen Mother).

Abatware (chiefs) - Tutsi chiefs for handling cow distribution & disputes. Hutu chiefs for land disputes.

Abiru (royal advisors).

Uburetwa, a system of bonded labor, tied Hutu farmers to Tutsi patrons through the ubuhake patron-client relationship. Hutu provided labor in exchange for protection and access to cattle products like milk. Refusal to work led to loss of access to cattle or land.

The Rwandan Kingdom experienced periods of peace but also internal conflict, including cattle raids, forced starvation of peasants, famine, and succession crises like the 1600s civil war between claimants Rujuira and Ndabarasa. At times, the kingdom expanded by conquering neighboring polities and selling war captives as slaves.

As cattle became more valuable in the Kingdom, the Mwami King introduced a tax on cattle, contributing to the westward migration of some Tutsis to the Kivu region in modern day Congo. These migrants are known as Banyamulenge, a Tutsi group that will be very important when we discuss the Rwanda-Congo conflicts.

The Reign of King Rwabugiri

In 1852, King Kigeri IV Rwabugiri, one of Rwanda’s most revered monarchs, led an expansionist campaign, annexing territories like Gisaka and boosting the kingdom's power.

Rwabugiri was a defender and conqueror who expanded the Rwandan Kingdom while resisting Swahili Afro-Arab slavers and delaying European colonization. He also fortified his kingdom’s borders, though peripheral regions did trade slaves with Afro-Arab traders. Rwandans traded ivory, cattle, and hides for textiles, beads, rifles, spices, and salt (a food preservative) with Swahili and Hindu traders, the latter focused purely on commerce.

Rwabugiri’s campaigns extended Rwanda’s territory, defeating the Kingdoms of Burundi and Ankole and vassalizing Ijwi Island. He strengthened tax systems and centralized power. His reign marked Rwanda’s height as a regional power.

In 1894, German explorer Gustaf Adolf von Gotzen entered Rwanda. Around the same time, King Rwabugiri embarked on an expedition to modern-day eastern Congo but died unexpectedly in 1895, likely from illness. His death left the kingdom in turmoil, triggering a succession crisis.

King Rutarindwa

Rwabugiri’s successor, Rutarindwa, assumed the throne but faced growing dissent from rival clans. In 1896, the Rucunshu Coup, led by rival clan factions, overthrew Rutarindwa, who, along with his closest allies, committed suicide to avoid capture. This coup destabilized the kingdom, weakened centralized authority, and left Rwanda vulnerable to Swahili Afro-Arab slave caravans kidnapping Rwandans at the kingdom’s periphery.

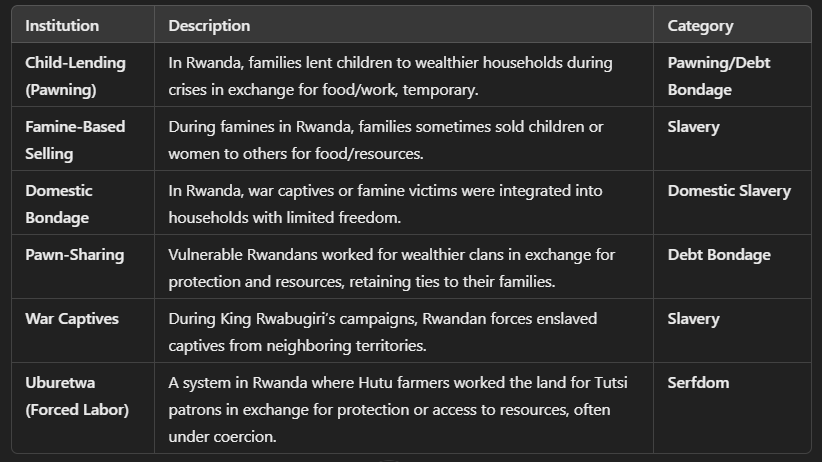

An Aside: Indigenous slavery in Rwanda?

The Kingdom of Rwanda had institutions resembling slavery, while others align more closely with pawning, debt bondage, or serfdom. Drawing from A History of Rwanda: From the Monarchy to Post-genocidal Justice and The Fate of Africa, I organized examples of these systems, categorizing them based on whether they constituted slavery or other forms of oppression.

In summary, Uburetwa functioned as serfdom. Pawning would resemble “child slavery” today. In severe famine, some families permanently sold children, aligning with slavery as individuals were treated as commodities.

Domestic servants, often war captives, were bound to their masters but could sometimes marry into the household. Pawn-sharing saw entire families pledging themselves to a wealthier patron for protection. For all of these cases, treatment varied widely, from abuse (e.g., rape, physical violence) to relative kindness, depending on circumstances.

Given the socioeconomic divide—Hutus as peasants and Tutsis as elites—these systems often appeared as Tutsi domination over Hutus. By the 1959 Hutu Social Revolution, ALL of these practices were labeled as Tutsi “enslaving” Hutus.

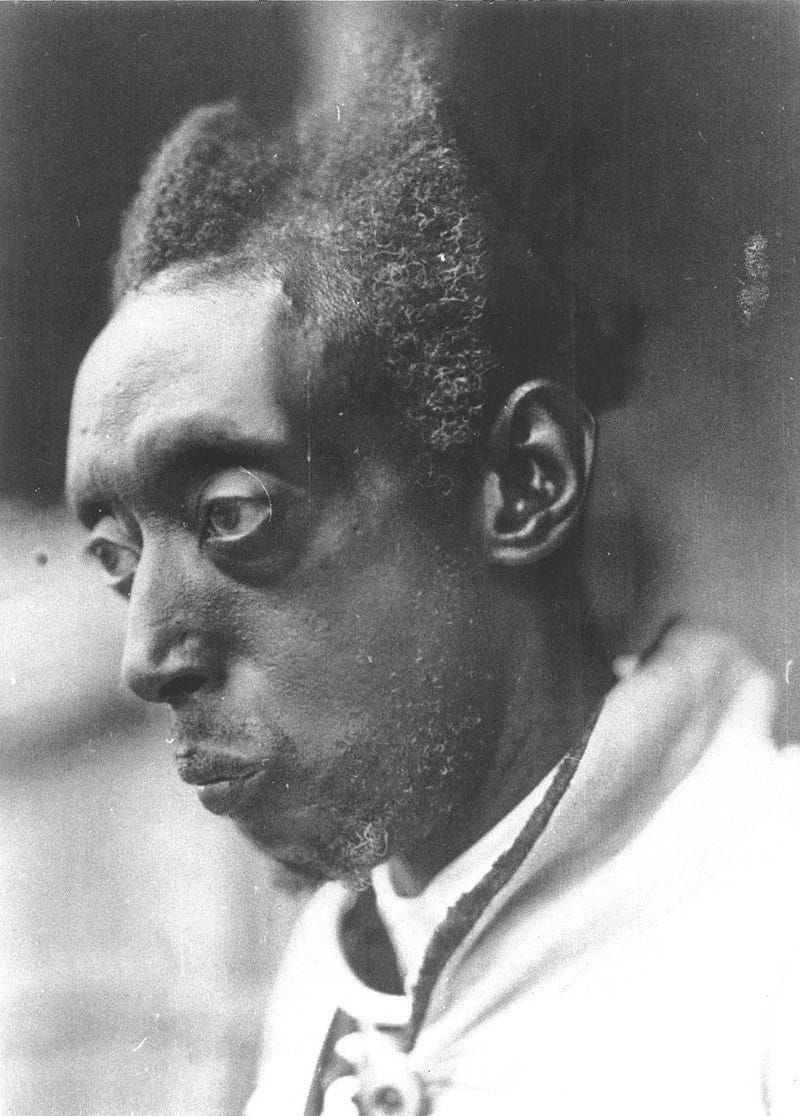

King Musinga

In 1896, the teenager, Tutsi King Yuhi V Musinga, succeeded Rutarindwa as Mwami.

Musinga's ascent through a coup left his legitimacy in question. Amid regional defections and Swahili Afro-Arab raids following Rwabugiri's death, Musinga sought to solidify his rule by allying with German soldiers due to their industrial technological superiority.

In 1897, German travelers began negotiating with Musinga, whom they described as a weak and arbitrary ruler. By 1898, Musinga signed a treaty with German explorer Von Gotzen, agreeing to make Rwanda a German protectorate in exchange for support to secure his throne. For Musinga, this was a desperate bid to preserve the kingdom and prevent another coup. He could not even read the treaty.

German Rwanda (1898-1916)

Rwanda and Burundi were administratively grouped as part of German East Africa, which also included Tanganyika (modern-day Tanzania). The colonial administration was based in Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika.

German rule in Rwanda was indirect, relying on existing structures of Tutsi dominance. Musinga retained significant autonomy, with the Tutsi-Hutu caste system remaining intact. During this time, if any Rwandan clan tried rebelling, Germany would give Musinga weapons to quell the rebellions (especially the Hutus and the North), cementing Musinga’s rule.

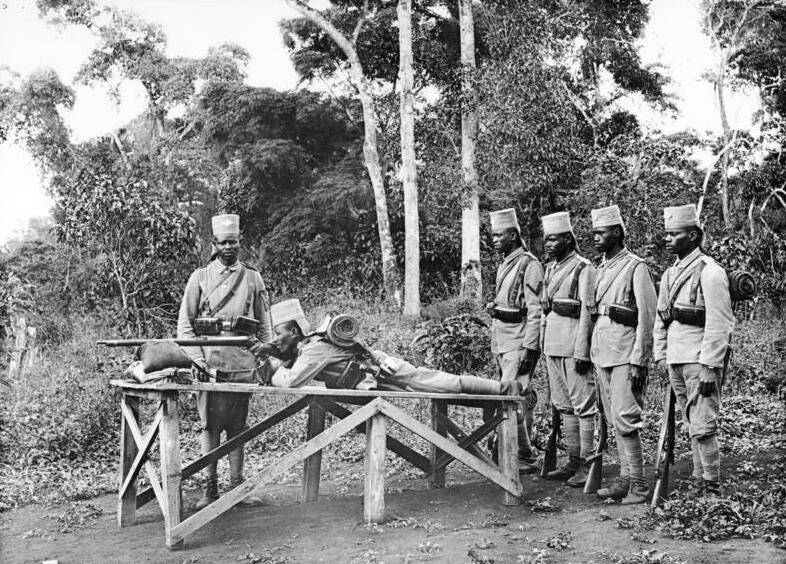

Germany governed through Musinga, Tutsi chiefs, and Askari (local African soldiers pledging loyalty to Europeans) to reduce administrative costs, with only a few dozen German officials overseeing a population of 1.6 million Rwandans. Most Rwandans never encountered Germans, as enforcement was left to Tutsi chiefs.

#1 Forced Labor and Taxes

The Germans used carrots and sticks to ensure compliance. Tutsi chiefs who enforced German policies effectively were rewarded with infrastructure improvements; those who failed faced punishments, including beatings. Chiefs organized forced labor, compelling Hutu farmers to build roads and plantations, a task made easier as the uburetwa system (a pre-existing forced labor practice) was already in place. The Germans added head taxes, payable in livestock or produce, which burdened subsistence farmers. Failure to pay taxes or meet labor quotas often resulted in flogging, increasing Hutu resentment.

#2 Economic Challenges

German Rwanda was unprofitable. Cash crop production, such as coffee, was experimental and marginal. Subsistence farming and barter systems dominated the economy, with most people being paid “in kind” with crops or livestock. Transporting perishable goods like vegetables and bananas to European markets was impractical. German Rwanda only sold a meager amount of animal skins.

#3 Christian Missionaries and Cultural Impact

Prior to colonialism, Rwandan education was informal and home-based. Fathers, grandfathers, and uncles taught itorero for boys, which focused on military and leadership training, while girls learned child-rearing & social etiquette by their moms, aunties, and grandmothers in urubohero.

French Catholic missionaries, known as the White Fathers, established schools (teaching Christianity, how to read, write, and do math on paper) and began eroding Rwandan traditional religion and polygamy. Missionaries also provided aid during famines.

#4 Stereotyping and Racism

German anthropologists and missionaries reinforced stereotypes, claiming Tutsis were taller, slimmer, and had narrower noses, while Hutus were shorter and broader. These racialized narratives laid the foundation for later divisions.

#5 Slavery and Trade

Germany banned the Arab slave trade and most forms of servitude in Rwanda, except for domestic servants and Hutu serfdom. Swahili Afro-Arabs and Indian traders shifted to acting as intermediaries in Kigali’s markets. Unlike Tanganyika, where Arab slavery was widespread, it remained minimal in Rwanda despite exaggerated missionary reports.

#6 Border Adjustments and Elite Discontent

As part of colonial border agreements, Germany ceded parts of Rwanda to British Uganda and Belgian Congo, angering Rwandan elites.

Belgium Rwanda (1916-1962)

Belgium’s Takeover:

In 1916, Belgian troops from the Congo ousted Germany from Rwanda and Burundi. After World War I, the League of Nations granted Belgium a mandate to colonize govern these territories and prepare them for self-rule.

Like Germany, Belgium’s administration in Rwanda was tiny. Belgium brought 200 Belgium soldiers with ~700 black soldiers with administer Rwanda.

Belgium’s Interventions:

Compared to Germany, Belgium, due to the League of Nations mandate, was very interventionist in their rule. They did the following:

Economic & Agricultural Changes: Belgium transitioned Rwanda from a barter-based economy that exports cow hides to one centered around cash crops, introducing the Congolese franc as currency. Coffee beans and tea leaves became the backbone of the economy, but drought, locusts, crop failures, and the focus on cash crops over staple foods led to recurrent famines, including Rumanura (1917–1918), Gakwege (1928–1929), and Ruzagayura (1943–1944). Subsistence farmers, already struggling under harsh taxes, were forced into a redesigned labor system called "akazi", building roads, churches, and bridges or cultivating crops far from home. Rwandans who didn’t meet their production quotas were flogged or sent in prison. Many Rwandans fled to British Uganda, British Tanganyika, or Belgian Congo for better opportunities, increasing the population of Banyamulenge (Congolese Tutsi and Hutu).

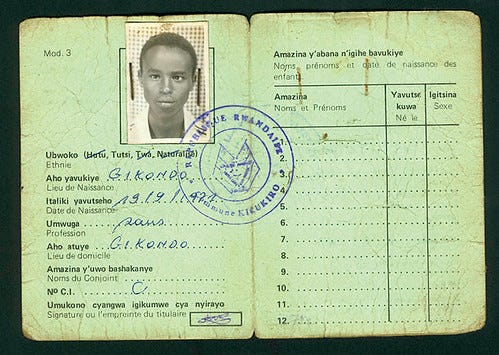

Transformed a Caste System into a Race: Belgium transformed Rwanda's Hutu-Tutsi caste system into rigid ethnic categories. In 1930, identity cards were issued, classifying individuals as Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa based on cattle ownership (Belgium declared 10+ cows meant Tutsi, fewer meant Hutu, forest dwelling dwarfs were Twa). By misinterpreting caste as ethnicity, Belgium institutionalized divisions, replacing Rwanda’s traditional clan-based system with fixed categories.

Weakening the Monarchy: Belgium systematically eroded the power of the Mwami (King). Traditional roles like the Abiru (royal advisors) and Umuganura (agricultural advisors) were abolished, and chiefs were no longer appointed by lineage but selected by the Belgians based on performance in Catholic schools, such as the White Fathers’ Nyanza School. King Musinga, who resisted Catholicism and Belgian reforms, was deposed in 1931. His son, Mutara III Rudahigwa, became the first Catholic Mwami, aligning the monarchy with Belgian interests.

Education Reforms: Belgium replaced Rwanda’s traditional informal education system with secular and Catholic schools. With formal schooling, Belgium gradually transitioned Rwanda from an illiterate society based on oral memory to a literate society with words written down. By 1945, 100,000 Rwandans attended primary schools, learning literacy, math, and writing. Belgian schools promoted the Hamite Hypothesis, claiming Tutsis were Ethiopian "African Caucasians" who conquered Bantu Hutus, a narrative Hutus used to unite against the Tutsi monarchy as foreign colonizers.

Healthcare Investments: Before Belgian reforms, Rwandans used natural herbs (imiti gakondo) took treat malaria and headaches. Belgium introduced vaccines, hospitals, and modern medicine, reducing child mortality, maintaining high birthrates. and increasing life expectancy. The population doubled from 1.36 million to 2.75 million in 40 years. However, without agricultural reforms to match this growth, Rwanda remained vulnerable to famine, and resource scarcity intensified tensions between Rwandans.

Post-War Shifts and the Rise of Hutu Nationalism

After World War II, America and the Soviet Union changed the international system. Where the League of Nations legitimized colonialism with the mandate system, both Stalin and FDR opposed colonialism and were rhetorically committed to the principle of self-determination.

The UN made oversight organizations that increased security on Belgium’s colonial practices. Many Rwandans, especially Hutus who worked in British Uganda & Tanganyika, left Belgian Rwanda because “they were tired of being beaten”. Hutus returning from British colonies brought ideas of emancipation, socialism, and Pan-Africanism, fueling calls for change.

By the 1950s, Hutu activists, many educated in Catholic seminaries, began framing the Tutsi monarchy & Tutsi history as oppressive.

By 1955, Belgium allowed Rwanda to form political parties. Here were the main ones:

1. UNAR (National Rwandan Union): Anti-Colonialist, Pro-Tutsi Monarchy

2. PARMEHUTU (Party of the Movement of Hutu Emancipation): Anti-Monarchy, Pro-Hutu

3. RADER: Pro equality between groups, Pro-Belgium

PARMEHUTU was the most popular by far. The founders of PARMEHUTU wrote the 1957 Hutu Manifesto, which denounced Tutsi dominance and demanded political and social equality. Belgian reforms, including local elections, initially favored Tutsis due to their literacy advantage, but Hutu political organization quickly gained momentum.

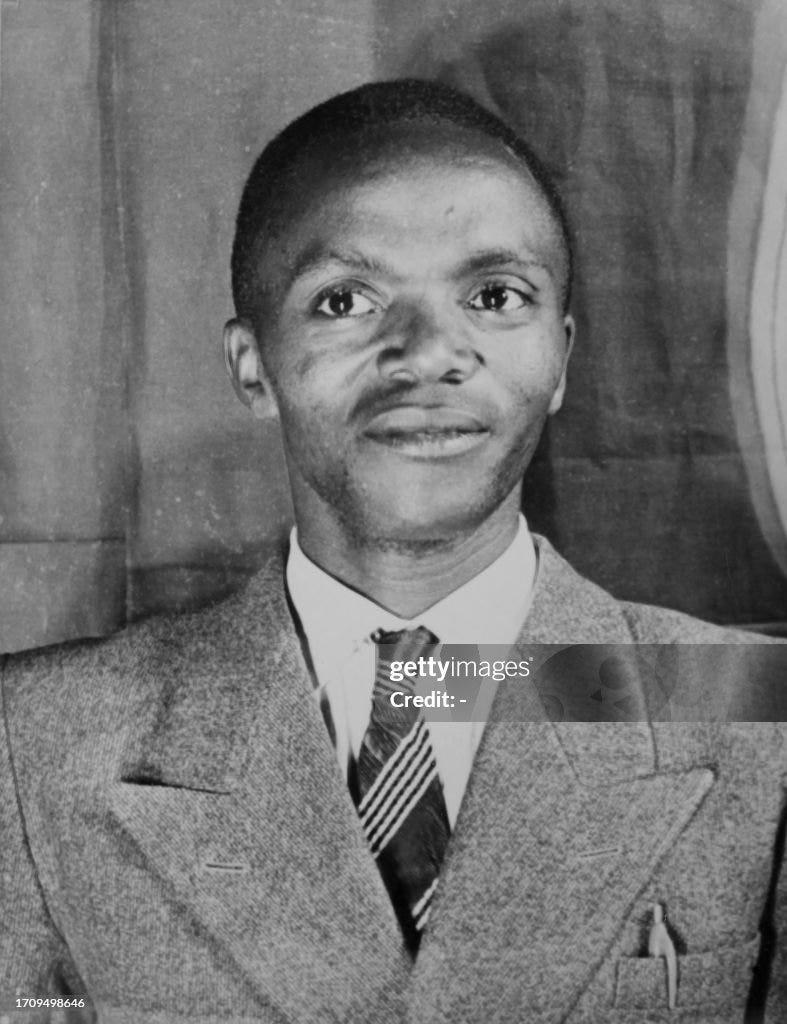

The Catholic Church, once aligned with the Tutsi elite, shifted its support to the Hutu majority. Hutu leaders like Grégoire Kayibanda galvanized the population by redefining abolished traditional labor systems like uburetwa and ubuhake as forms of slavery and rallying against Tutsi rule.

Ironically, by the 1950s, Hutu and Tutsi barely differed in household income. Tutsi incomes exceeded Hutu incomes by 5%. Regardless, Hutu nationalism was powerful, based on historical grievance and collective identity.

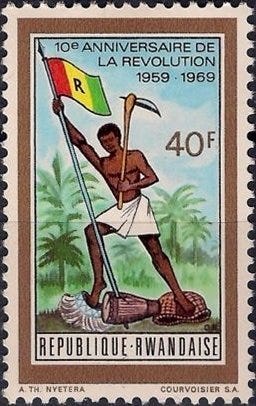

1959 Hutu Revolution

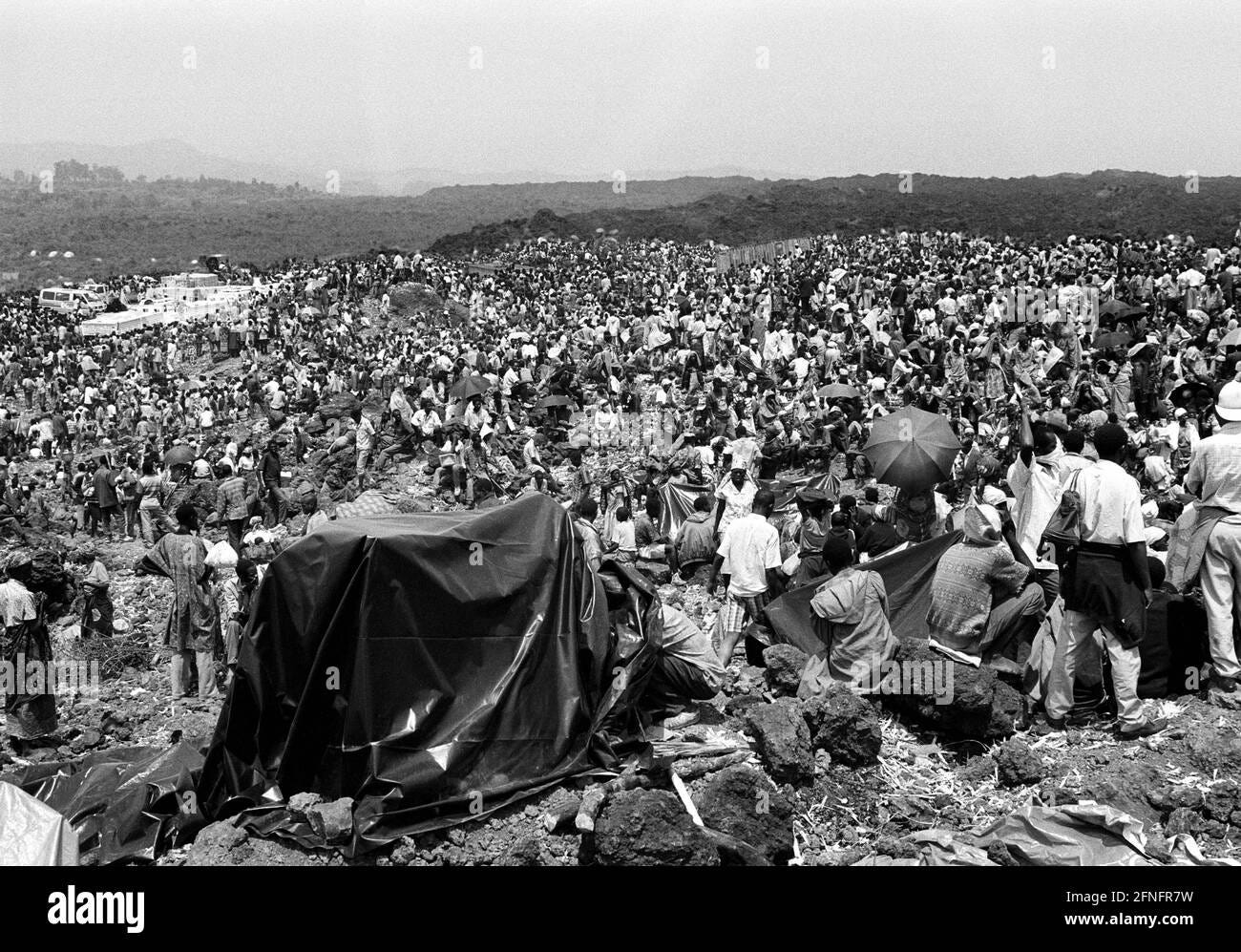

King Rudahigwa’s 1959 death in a Burundian hospital, rumored to involve Belgian foul play, fueled tensions. Believing Belgium supported Hutus to end the Tutsi monarchy, Tutsi militants attacked Hutu chiefs. In response, angry Hutus, tired of the monarchy, launched the “wind of destruction” or "Hutu Revolution" (Muyuga), burning Tutsi homes, killing 20K Tutsis, and displacing over 130,000 Tutsis to flee to Congo, Tanganyika, Uganda, and Burundi. Belgium, fearing civil war, backed the Hutu majority, replacing Tutsi chiefs with Hutu administrators. Outnumbered, Tutsi resistance failed.

Rudahigwa’s son, Kigeli V, was the new Tutsi King. But by 1960, elections saw the PARMEHUTU dominate with Gregoire Kayibanda as leader, and he abolished the Tutsi monarchy in 1961. Rwanda gained independence in 1962.

The United Nations thought all of this was insanity as they reported, “The developments of these last 18 months have brought about the racial dictatorship of one party… It is quite possible that some day we will witness violent reactions on part of the Tutsi.”

Concluding Thoughts

Rwanda, like Sudan, Burundi, Ethiopia, and Uganda, escaped the European transatlantic slave trade but remained an unindustrialized, subsistence economy.

When the expansionist, King Rwabugiri, died on his campaign in modern day Congo, succession crises nearly collapsed the monarchy. Teenage King Musinga, unable to read, signed a treaty with Germany, thinking it would save his kingdom.

German colonial rule was lite, but Belgian colonialism deeply transformed Rwandan society by redefining Hutu and Tutsi as racial categories rather than castes. With rising political consciousness, the Hutu elite overthrew the Tutsi monarchy in the Hutu Revolution, expelling hundreds of thousands of Tutsi—a precursor to the events of the 1994 Rwanda Genocide, an event we will discuss in Part II.

this is totally interesting/excellent. big admirer of economic history like this. Makes a great argument for simply leaving people alone.

This caste seems like it has ethnic origins. Just looking at their bone structure, the Hutus and Tutsis remind me of the Hausa-Fulani of North-West Africa. With the more pastoral Fulani forming a ruling minority over the Hausa farmers.

Cattle rearers vs Farmers. The tale of civilization