The Economic & Geopolitical History of Rwanda Part II: Post Independence Struggles, The Rwandan Civil War, & The Precursor to Genocide

What happened in Rwanda before the genocide? Let's find out

In Part I, we explored Rwanda's pre-colonial and colonial history. Rwanda was a monarchy where Tutsi aristocrats owned cattle, and Hutu commoners farmed. After the expansionist King Rwabugiri died on an excursion to modern-day East Congo, the monarchy became unstable. His successor, a teenager named Yuhi Musinga, signed a treaty with Germany, making Rwanda a protectorate in exchange for stabilizing Rwanda. After WWI, Belgium took over, transforming the class-based Tutsi-Hutu system into a ethnic divide. Before independence, under Hutu leader Dominique Mbonyumutwa, the "Umuyaga" revolution killed tens of thousands of Tutsi and expelled 130K of them to neighboring countries like Tanganyika(Tanzania), Uganda, Burundi, and Zaire(Congo), establishing a Hutu supremacist state.

Grégoire Kayibanda (1962-1973)

Economy: Post-Independence Struggles

Failed Pan-Africanism

Rwanda and Burundi initially shared a monetary union, sharing a central bank and currency. But their stark political differences—Burundi as a traditional, Tutsi-led monarchy and Rwanda as a revolutionary, Hutu supremacist republic—strained relations. The Hutu Revolution (1959-1961) in Rwanda displaced over 100K Rwandan Tutsi refugees into Burundi alone, escalating tensions and prompting both countries to establish separate central banks & currencies. This was a disaster for Rwanda as it had little in foreign currency reserves at the start.

Aid-Ridden at the Start

Rwanda’s economy, heavily reliant on coffee beans & limited tin exports, was ill-prepared for independence. As an agricultural economy, it remained vulnerable to climate shocks like droughts and soil degradation. The internal tax collection was insufficient for expansion of education and roads. To keep the state afloat, Belgium, France, and the European Development fund continuously provided aid to Rwanda.

Unsuccessful Development Plans

President Kayibanda launched an ambitious five-year plan aimed at increasing cash crop exports, developing light manufacturing, and improving road networks. However, the plan fell short. State-owned marketing boards collected coffee beans from farmers for export but paid them poorly. With little financial incentive, farmers struggled to meet production targets, undermining the plan’s success.

Rwanda had limited manufacturing in the 1960s, with a few key firms: Bralirwa Brewery, which gained investment from the Dutch firm, Heineken, in the 1980s; SOTEXKA, a textile company; and ALUMINAR, an aluminum factory. The government also partnered with Belgian investors to establish light manufacturing ventures. Other industries included coffee and tea processing, a few flour mills, and a cigar factory.

Financial Instability

After independence, Rwanda faced immediate financial struggles, running large deficits and relying on foreign loans to fund public services. By 1966, Rwanda was bankrupt, relying on $12 million, low-interest, IMF emergency loans to address its balance of payments crisis. Rwanda restricted imports, mainly motorbikes and clothes, through a licensing system to conserve foreign currency, but rampant black-market trading undermined the policy. The IMF advised devaluing the Rwandan franc from 50 to 100 Rwandan francs per dollar to make exports more competitive, though simultaneously this made imports more expensive, triggering inflation and angering the population. By 1970, increased coffee production temporarily stabilized Rwanda’s economy, reducing its reliance on IMF loans for some time.

France-Afrique:

Although France did not colonize Congo or Rwanda, their French-speaking populations, a legacy of Belgian rule, drew France into close ties. France’s Cellule Africaine handled intelligence, diplomacy, and bribery in Rwanda.

Political Developments: Hutu Supremacy

In 1962, Hutu supremacist Grégoire Kayibanda became president, using Tutsi oppression to solidify his power. He banned Tutsi from certain jobs and limited their access to education, fueling the nationalist "Hutu Power" movement. Using colonial pseudoscience, Hutu Power framed the Tutsi minority (15% of the population) were Ethiopian interlopers, despite Hutu and Tutsi being ethnically the same. Kayibanda declared Rwanda, a nation divided:

The Hutu elite used hateful rhetoric to justify lynching Tutsi, framing it as a way to unite Hutu in a struggling post-independence economy. Once Kayibanda’s PARMEHUTU party took power, they quickly eliminated opposition and made Rwanda a one party state.

Kayibanda dismantled ubuhake, the traditional, cattle-based, feudal system binding Hutu servants to Tutsi masters, and abolished the Tutsi monarchy, forcing the Tutsi king to flee to Tanzania.

Rwanda’s Issues with Neighbors:

After the Hutu Revolution, the 100,000+ Tutsi exiles in Tanzania, Congo, Burundi, and Uganda formed groups to reclaim Rwanda. Leaders like Mobutu (Congo) and Obote (Uganda) urged Kayibanda to accept the Tutsi refugees, but he refused.

Kayibanda’s interior minister, Alexis Kanyarengwe, solidified this exclusion by issuing property titles to Hutu who occupied Tutsi property, cementing Tutsi exclusion.

In addition, during colonial rule, border treaties by Belgium, Germany, and Britain shifted regions like Ijwi and Gishari from Rwanda to Congo and Bufumbira to Uganda. This left Banyarwanda (ethnic Rwandans) and Tutsi exiles scattered in Congo and Uganda, blurring the line between Tutsi refugees and Tutsi long-time residents, as most carried no passports. While Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere integrated Tutsi exiles as citizens, many Tutsi refugees in Uganda and Congo often joined their host nations’ armies, influencing their foreign policy on Hutu-led Rwanda, or formed militias to oppose the Hutu-led state.

Tutsi massacres or Inyenzi (cockroach) slaughters:

In 1962, Rwandan Tutsi refugees in Burundi attacked Rwanda, prompting Kayibanda to retaliate, killing 2,000 Tutsi exiles & Rwandan citizens.

Later in December 1963, Rwandan Tutsi exiles in Tutsi-led Burundi, launched the Inyenzi ("cockroach") attacks on Rwanda. Kayibanda’s government, with Belgian support, repelled the attack, killing the rebels and labeling Tutsi in Rwanda a "fifth column." Kayibanda executed 20 Tutsi politicians and used Radio Kigali to warn of Tutsi "terrorists" seeking to reclaim power.

Local PARMEHUTU officials formed "self-defense" groups, and Hutu militias expelled or killed Tutsi, swelling the refugee population to 336,000, with 200,000 in Burundi. In January 1964 in Rwanda, 15,000 Tutsis were killed in Gikongoro, and 100 Tutsi women and children were drowned by mobs in Shigiri.

The killing of exiled Tutsi fighters (Inyenzi) boosted Kayibanda’s popularity. A Rwandan official told academic René Lemarch that, “Before attacks on the Inyenzi, the government was on the point of collapse. Not only have we survived the attacks but the attacks have made us survive our dissensions.”

Tutsi exiles ceased attacks on Rwanda, realizing their violence fueled lynchings within Rwanda. Nonetheless, Kayibanda continued to use the threat of "Tutsi terrorists" to legitimize Hutu rule. Quotas limiting Tutsi representation in civil service, education, and state enterprises to 15% were codified into law by 1971, while bribery and false ethnic identity claims became common. Kayibanda outlawed identity changes in 1970, basing ethnicity on colonial stereotypes, deepening divisions.

Regional Divides

Besides the Hutu-Tutsi split, there was also the Northerner-Southerner Hutu split.

Kayibanda, a Southern Hutu, heavily favored Southern Hutu, his primary base of support, while sidelining Northern Hutu, who largely dominated the military. This created significant tensions between the party and the army. Regional divisions deepened as some Southern Hutu considered themselves more "authentic" Hutu, viewing Northern Hutu, whose territories were historically annexed by King Rwabugiri in the 1800s, as less authentic. As a Southerner, Kayibanda directed patronage toward his region, further exacerbating mistrust and rivalry between the North and South.

Tutsi-led Burundi’s Impact on Hutu-led Rwanda

Kayibanda often pointed to Burundi’s instability to justify his actions. Since 1962, Burundi, under its Tutsi monarchy, had been more turbulent than Rwanda, with two prime ministers assassinated and seven governments in rapid succession. In 1965, a Hutu mutiny led to brutal reprisals against Burundian Hutu leaders. After a 1966 coup, Burundian Tutsi President Michel Micombero purged Hutu from Burundi’s army and government, executing many Hutu politicians and soldiers to eliminate the "Hutu threat."

In 1967, Kayibanda cited the ethnic cleansing and massacres of Hutu by Tutsi in Burundi as justification for the persecution and killing Tutsi in Rwanda. Relations between Hutu-led Rwanda and Tutsi-led Burundi were hostile.

The 1972 genocide of Hutu by Burundi’s Tutsi rulers, which killed 200K Hutu and drove another 200,000 Hutu refugees into Rwanda, further entrenched anti-Tutsi sentiment in Rwanda.

Kayibanda responded to the mass slaughter of Hutu in Tutsi-led Burundi, by saying “Tutsi domination is the origin of all the evil. The Hutu have suffered since the beginning of time.”

Social and Economic Fallout

With Rwandan Tutsi excluded from public administration, many turned to academia and business, dominating these sectors disproportionately and fueling resentment mirroring European antisemitism towards Jews. Kayibanda’s regime formed "cleansing committees" to blacklist Tutsi teachers and students, expanding into xenophobic campaigns targeting not only Tutsi but also Northern Hutu. Southern Hutu demanded schools, businesses, and foreign embassies be purged of Tutsi influence, leading to school closures as many teachers were Tutsi. Violence escalated, with burned Tutsi huts and increased clashes between Southern and Northern Hutu.

During all of this violence, more Tutsi fled to Congo, Kenya, Tanzania, Burundi, and Uganda. Mobutu of Congo would grant Tutsi citizenship in 1972, but then revoked it in 1981.

Political Collapse and Coup

By the 1970s, the country was on death’s door. To maintain power, Kayibanda began purging Northern Hutu from government and the army while drafting a new constitution to extend his authority. He dismissed Juvenal Habyarimana, a Northern Hutu and Secretary of State, triggering a coup in 1973. Habyarimana, backed by the Northern-dominated military, ousted Kayibanda and arrested/killed Kayibanda and his Southern allies. This coup marked the rise of Northern Hutu dominance in Rwanda’s politics, deepening regional and ethnic divisions.

Juvenal Habyarimana (1973-1994)

Habyarimana introduced a new constitution prohibiting discrimination based on ethnicity/lineage, however, Hutu-Tutsi quotas persisted unofficially. Only five Tutsi were allowed in government, and Hutu soldiers were forbidden from marrying Tutsi women. His party, the Revolutionary Movement for National Development (MRND), established Rwanda as a one-party state dominated by Northern Hutus, who now controlled cabinet positions, administration jobs, state owned enterprise hirings, development funds, and foreign scholarships. Habyarimana consistently won elections with implausible margins of 98%.

Compared to his predecessor, Kayibanda, Habyarimana's regime was more stable, received a decent amount of tourism, and attracted significant development aid, becoming a "donor darling" for West Germany, Belgium, and France. In 1973, foreign aid was 5% of national income, by 1991, aid was 22%. The Catholic Church made more hospitals and Rwanda aligned with the West in opposing the Soviet Union. Belgium and France bolstered Rwanda’s military with training and weapons. Habyarimana also revived a colonial-era policy requiring citizens to dedicate half a day's work to infrastructure projects.

Habyarimana opposed the return of exiled Tutsi, claiming Rwanda’s population density made it impossible to accommodate them. When Obote of Uganda expelled over 25K Tutsi refugees in 1982, Habyarimana forced most back to Uganda or killed them, accepting only 4,000.

Rwanda's "growth" under Habyarimana was mainly driven by coffee bean exports, which accounted for 80% of Rwanda’s foreign currency earnings in the 1980s. State-led manufacturing in aluminum, textiles, and beverages stagnated, and tin mining made meager revenues. 90% of the population remained subsistence farmers.

Coffee price Crash!

In the late 70s & again in the 80s, crashes in global coffee prices, driven by international market oversupply and the collapse of the International Coffee Agreement cartel, devastated Rwanda’s economy, as coffee beans made up 40% of GDP, 80% of foreign currency earnings, and sustained the livelihoods of 90% of Rwandan subsistence farmers.

The economic collapse led to rising crime, famine, corruption & patronage in Habyiarmana’s government, compounded by the HIV/AIDS crisis. Efforts to diversify into tea or banana failed to offset the growing pressures of land scarcity and population growth, leaving Rwanda in a Malthusian trap.

Rwanda’s economy was declining and so was Habyarimana’s government budget. It also didn’t help that in 1988, Tutsi-led Burundi expelled 50K Burundian Hutus to Rwanda.

Meanwhile, Uganda underwent seismic changes. In 1986, Yoweri Museveni, with the help of exiled Rwandan Tutsi like Paul Kagame and Fred Rwigyema, overthrew the Okello government in Uganda. Museveni integrated some Tutsi refugees into Ugandan society, granting them military training and citizenship. Kagame became deputy commander of military intelligence, while Rwigyema became Uganda’s minister of defense. Museveni criticized Habyarimana’s government and openly defended Tutsi refugees at the UN, attracting Tutsi exiles from Tanzania, Burundi, and Congo to Uganda. In 1987, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) was formed, driven by Tutsi refugees’ growing realization to reclaim their homeland, as they were resented as middleman minorities in Uganda like Chinese in Malaysia, Jews in Europe, or Igbos in Nigeria.

Tensions grew in Northern Uganda as rebel groups accused Museveni of favoring Tutsi refugees over native Ugandans, strengthening the resolve of Rwandan Tutsi to reclaim their country. By 1990, Museveni, backed by Western donors and the UN, pressured Habyarimana to allow Tutsi exiles to return. Publicly agreeing but stalling in practice, Habyarimana opposed their return while appeasing international critics. By then, the Rwandan Tutsi exile community exceeded 500,000.

Rwandan Civil War (1990-1994)

In October 1990, the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), led by Tutsi exiles, invaded Rwanda from Uganda. The attack failed, and its commander, Fred Rwigyema, died on the 2nd day of the invasion. Habyarimana, with French troop protection detained 13K Tutsi in Rwanda. Many were tortured and died.

Soon after, rumors of RPA retaliation sparked the Kibilira massacre, where Hutu murdered 300 Tutsi under the guise of self-defense.

Paul Kagame became the new commander, and Kagame’s leadership made the RPA more efficient via hit-an-run raids, destabilizing northern Rwanda, as Museveni supported the insurgency with weapons and food.

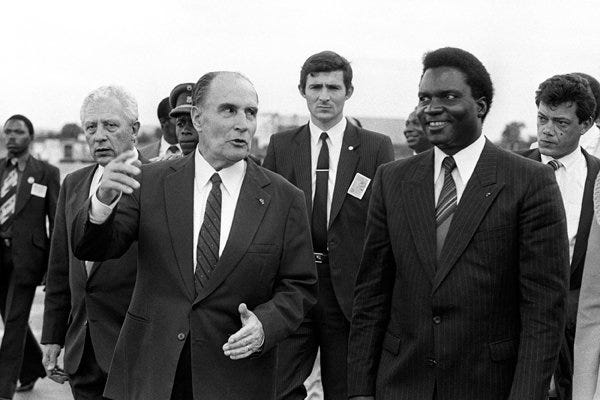

To get more foreign help, Habyarimana secretly staged an attack on his capital to justify his request for help. Mobutu of Congo, Mitterrand of France, and Dehaene of Belgium rushed to provide Habyarimana arms. Although, France became a key ally, while Belgium urged moderation, earning hostility from Hutu extremists. Since Congolese Tutsi were joining Kagame’s RPF, Mobutu relinquished citizenship of all Congolese Tutsi, even the ones that have been in Congo for a century, the Banyamulenge.

During the civil war, France trained more troops for Habyarimana, and Habyarimana secured arms contracts from Hosni Mubarak’s Egypt and Apartheid South Africa, buying $100M in arms supplies (equivalent to 33% of the Rwandan government budget in 1990). Habyarimana also took an IMF Structural Adjustment loan and used the loan to buy guns, machetes, and grenades instead of supporting poor Rwandan farmers.

The Rwandan army built up young civilian militias called the Interahamwe ("Those Who Stand Together") to fight back against the Tutsi RPF, target Tutsi in Rwanda, opposition journalists, and politicians. They replaced moderate mayors with hardliners and slaughtered thousands, especially in rural areas. To rally his Hutu base, Habyarimana blamed the Tutsi for economic woes, fueling the rise of the Hutu Power movement.

“The fatal mistake we made in 1959 was to let them [the Tutsi] get out… They belong in Ethiopia…. Wipe them all out!” — Hutu Power

The Akazu, also known as the “Le Réseau Zéro” or “Zero Network”, was an inner clique that collaborated with Habyarimana’s wife, Madame Agathe, to not just kill Tutsi but to conjure up a plan to murder moderate Hutu or "ibyitso" (traitors or Hutu that didn’t want to kill Tutsi). They influenced the army, security service, the administration, the universities, and the media to promote Hutu Power. The Free Radio and Television of the Thousand Hills or Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) played songs and hate-filled propaganda.

In December 1990, Hassan Ngeze, editor of Kangura (Basically Rwandan Daily Stormer), published the Hutu Ten Commandments, advocating for Hutu supremacy, segregation, and exclusion of Tutsi from public life.

The commandments became central to Hutu ideology, with Habyarimana endorsing them.

Kangura spread fears of a Tutsi war to "leave no survivors," intensifying tensions. He said anyone who married, befriended, had sex with, or employed a Tutsi woman was considered a “Race Traitor”.

Persecution of Tutsi escalated, with the government portraying the RPA as bandits and calling for revenge against Tutsi within Rwanda. Between 1990 and 1993, thousands of Tutsi were murdered, raped, tortured, and arrested alongside moderate Hutu. Fighting continued until the peace talks in Arusha, Tanzania, in 1993 led to the Arusha Accords, which outlined a power-sharing agreement. Habyarimana didn’t want to sign it, but he had no choice since his government was bankrupt and depended on food aid.

The accords were about the integration of the RPF into the national army, the return of multiparty democracy, and the return of Tutsi refugees with restored property rights. The more inclusive/democratic the government, the more aid Belgium was willing to dole out. So, Habyarimana also abolished ethnic quotas, opening government and education to Tutsi, which made Hutu Power apoplectic. In response, Hutu Power mobilized the Impuzamugambi ("Those with a Single Purpose") death squad militia, recruiting unemployed Hutu youth with promises of land, jobs, or money.

The bloodlust during this time was obvious. The Arusha accords were not signed for peace, but to stall time for mass murder. In fact, the Belgian ambassador reported to Brussels that “This secret group (Akazu) is planning the extermination of the Tutsi of Rwanda to resolve once and for all, in their own way, the ethnic problem and to crush internal Hutu opposition”.

In October 5th 1993, in accordance with the Arusha accords, the UN Security Council sent a mission called UN Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) to provide peace. The UN sent 2.5K peacekeeping forces to Kigali.

The Canadian UNAMIR commander, Roméo Dallaire, was short of vehicles, fuel, food, ammunition, radios, intelligence gathering capacity, barbed wire, medical support and even petty cash. Dallaire pleaded for reinforcements knowing that the Rwandan Hutu were planning a genocide, and the UN, under Secretary General, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, said no.

On October 21, 1993, extremist Tutsi officers in Burundi assassinated President Melchior Ndadaye, the country's first democratically elected Hutu leader, just four months after his election. His murder reinforced anti-Tutsi sentiment among Rwandan Hutu, who saw the assassination as proof-positive that Tutsi could not be trusted. The assassination triggered Burundi’s civil war, which lasted from 1993 to 2005. Also, 300K Burundians, mostly Hutu, fled to Rwanda in 1993.

The coup & civil war in Burundi deepened divisions in Rwanda despite the Arusha Accords. Rwandan Hutu extremists starting gunning down and lynching Hutu moderate politicians —a grim foreboding to one of humanity’s greatest recorded tragedies…

Conclusion

From independence to the brink of genocide, Rwanda saw little economic progress. European aid improved literacy, population growth, and higher life expectancy, but it couldn’t overcome inept governance, regional Hutu rivalries, or the lynching of Tutsi. Manufacturing stagnated, tin mining remained minimal, and 90% of the population relied on subsistence farming. The 1980s global coffee price crash plunged Rwanda into deeper poverty.

By the early 1990s, Museveni, repaying Rwandan Tutsi support in Uganda, backed Paul Kagame’s Rwandan Patriotic Front, igniting the Rwandan Civil War. Despite a ceasefire and UN peacekeepers, the Rwandan genocide still occurred, which you can read about in Part III.

We must notice that fascism doesn't only happen in the West.

I'm reminded of a comment made when South Carolina declared secession from the United States, that it's too small to be a country and too large to be an insane asylum. History may not repeat itself, but it does rhyme. So tragic!