The Economic & Geopolitical History of Rwanda Part III: The Rwandan Genocide & the 1st Congo War

One of the late 20th century's darkest events

Read Part I to learn about traditional, German, and Belgium Rwanda. Before independence, the 'Hutu Revolution' killed tens of thousands of Tutsi and expelled 130,000 to neighboring states, creating a Hutu-dominated state.

Read Part II to uncover the economic failures of the first two Rwandan Hutu Presidents, Kayibanda and Habyarimana, who scapegoated and oppressed Tutsi to mask their struggles. Ethnic/Caste killings between Hutu-led Rwanda and Tutsi-led Burundi forced many to flee across borders. This cycle escalated when Tutsi exile, Paul Kagame, led his Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) to invade Rwanda from Uganda, triggering the Rwandan Civil War (1990-1994). France, Belgium, and Congo intervened and backed Habyarimana, while Uganda supported the RPF. Extremist Hutu militias, including Hutu Power and the Akazu, lynched Tutsi and moderate Hutu during the war despite a UN presence.

The 1993 Arusha Accords in Tanzania aimed to establish a multiparty democracy integrating the Tutsi, but…

The Plane Crash as a Tipping Point

The April 1994 missile attack on Habyarimana’s plane, returning from Tanzania, became the spark for Hutu Power extremists to kill moderate Hutu and launch the Tutsi genocide.

The attack was a tipping point for the Hutu. Alongside Habyarimana, Burundi’s 1st Hutu president, Cyprien Ntaryamira, was also on the plane, marking the death of three Hutu leaders in Burundi and Rwanda within months. Habyarimana’s 20-year rule ended in chaos.

The missile’s origin is disputed: Kagame and his RPF blame Hutu extremists, while Hutu extremists & France accused Kagame —though France later retracted. Many point to the Akazu, a Hutu Supremacist clique which included Habyarimana’s wife, as the likely culprits.

Belgium & UN evacuation during the Genocide

During the genocide, the Hutu-led Rwandan Presidential guard killed moderate Hutu Prime Minister (PM) Agathe Uwilingiyimana and her UN escort of 10 Belgian peacekeepers. With the PM dead, Hutu Power extremists seized the power vacuum, targeting political opponents, including the Constitutional Court and the Arusha Accords negotiator.

Following the peacekeeper murders, Belgium and the UN withdrew in April. RTLM radio incited violence, urging Hutus to 'Go to Work' (slaughter Tutsi) and calling them 'inyenzi' (cockroaches). Military leader Théoneste Bagosora declared to the UN, 'The only plausible solution is the elimination of the Tutsi.'"

Rwanda Genocide

In just 100 days from April to July 1994, 200,000 Hutu extremists, including Interahamwe & Impuzamugambi death squads, massacred 800,000 to 1 million Tutsi and moderate Hutu—10-12.5% of Rwanda’s population of 8 million. Seventy-five percent of Tutsi and 25% of Twa were killed in churches, schools, and homes. Tutsi were targeted for Tutsi IDs, stereotypical "Tutsi features" (being tall, light skinned, or wealthy), and moderate Hutu were targeted for refusing to join the slaughter. Hutu radicials sang songs declaring, "Our enemy is the Tutsi," and even forced Hutu-Tutsi couples to kill their loved ones or die with them.

In Left to Tell, survivors like Immaculée Ilibagiza recalled neighbors turning into killers. Meanwhile, Western governments evacuated their citizens and ignored the genocide. The UN Security Council voted to reduce its troops from 2,500 to 270 on April 21, leaving Rwandan Tutsi defenseless.

France’s President Mitterrand supported Habyarimana’s extremist allies, the Akazu, aiding their escape and even gifting $40K to Agathe Kanzinga, Habyarimana’s widow.

Hutu extremists weaponized rape, spreading AIDS through sexual violence. Women were killed in maternity clinics, and babies were drowned. As international outrage grew, the killings became more covert. Though the UN authorized 5,000 troops on May 17 (Resolution 918), they lacked the equipment to save lives. Extremists silenced witnesses through murder to avoid international trials, while UNAMIR troops stood by, watching the genocide unfold from their hotel.

French “Help”

By May, the Paul Kagame’s Tutsi-led RPF controlled Kigali, the airport, and over half of Rwanda. France, however, backed its Hutu allies, portrayed the RPF as backward Africans aiming to revive traditional Tutsi feudalism and impose an unpopular regime that would be rejected by 85% of Rwandans.

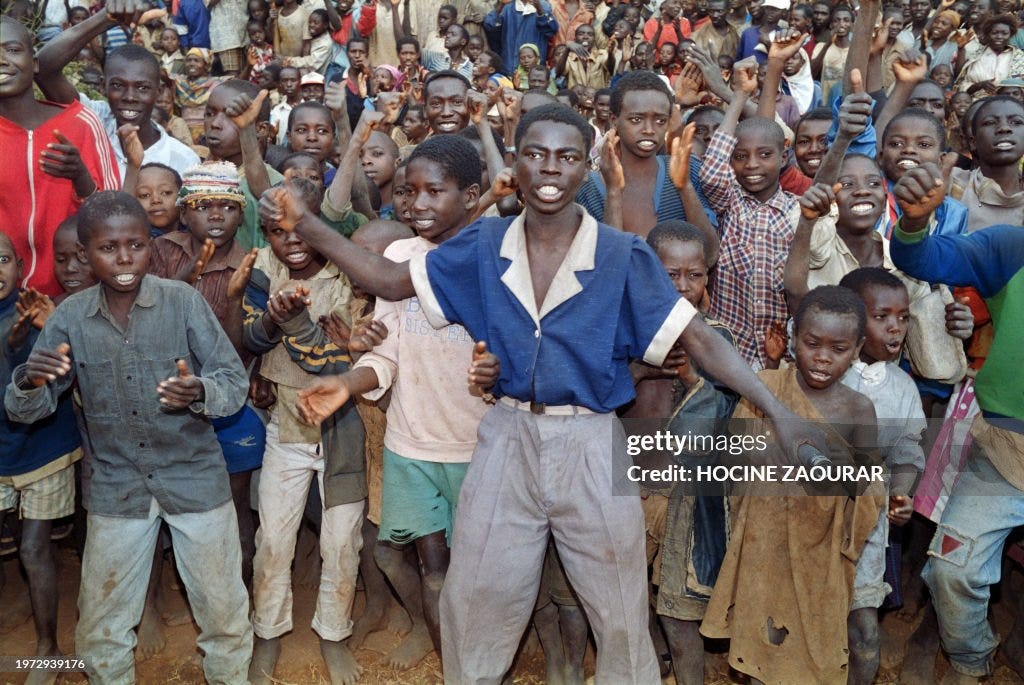

On June 2, French forces entered Rwanda from Bukavu, Congo, greeted as heroes by Hutu militias like the Interahamwe. Banners said “Vive la France”, while Radio Mille Collines encouraged Hutu women to dress up and marry a Frenchman.

By June 12, Kagame’s RPF captured Gitarama, forcing Hutu Power leaders to flee to their stronghold in Gisenyi. Hutu Power raided the national treasury for its remaining gold & foreign currency. Despite losing territory, Hutu militias intensified massacres, targeting moderates and Tutsi rather than defending their positions.

On June 14, fearing an RPF victory and possible revenge genocide against Hutus, French President Mitterrand proposed deploying troops. The UN approved Operation Turquoise on June 22, sending 2,500 French troops. French officials hinted at “breaking the back of the RPF,” reinforcing perceptions of bias toward the Hutu government.

UN Commander Dallaire opposed the French intervention, citing their history of arming the Hutu government and warning against further arms deliveries. France, tasked with creating a “blue safe zone”, faced accusations from Kagame’s RPF of supporting the regime. Dallaire warned:

Human Rights Watch reported that between May and June, Mitterrand and Mobutu of Congo facilitated five arms shipments from French firms to the Rwandan army via Goma, Congo aiming to prevent a Tutsi counter-genocide. However, France later admitted misjudging the situation, with one French officer conceding, “We were deceived... We were told the Tutsis were killing Hutus. We thought the Hutus were the good guys and victims.”

French and UN forces, constrained by a limited mandate, evacuated survivors to safe zones but failed to stop the genocide, as Hutu militias continued their massacres.

Haunted by the failed 1993 U.S.-led UN mission in Somalia, which left 18 Americans dead, the U.S. and UN hesitated to intervene during the Rwandan Genocide. As embassies closed and diplomats fled, Hutu militias intercepted and killed escaping Rwandans. UN officials admitted, “We were cautious... because we did not want a repetition of Somalia.”

Hutu supremacist radio RTLM incited violence, broadcasting ethnic fear and identifying Tutsis for militias at roadblocks, declaring, “We kill them before they kill or enslave us again.” Emboldened by international inaction, genocidaires carried out massacres in plain sight. This prompted UN General Romeo Dallaire to condemn the “inexcusable apathy.”

France’s Operation Turquoise faced accusations of shielding genocidaires. Critics, including former Rwandan ambassador Jacques Bihozagara, alleged the operation allowed Hutu militias to escape to Congo and regroup. Witnesses like Isidore Nzeyimana claimed French officers supported Hutu militias, and Kagame stated, “France helped the Hutus facilitate the killings.”

By spring 1994, Kagame’s Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) resumed attacks. Despite French support for the Hutu army, the RPF captured Kigali and Butare by July, killing tens of thousands of Hutu militia fighters. As 250,000 Hutus fled to Tanzania fearing revenge, the RPF declared a ceasefire, established a new government, and helped the UN remove extremists like Jean-Baptiste Gatate.

Paul Kagame (1994-Present)

Rwanda, post-genocide, was in ruins: the police force was disbanded, the treasury was empty, harvests were destroyed, diseases were rampant, infrastructure was destroyed, and corpses were everywhere. Over 500,000 children were orphaned, and women were raped, often contracting AIDS. It was the 5th poorest nation on earth at the time, tied with Somalia.

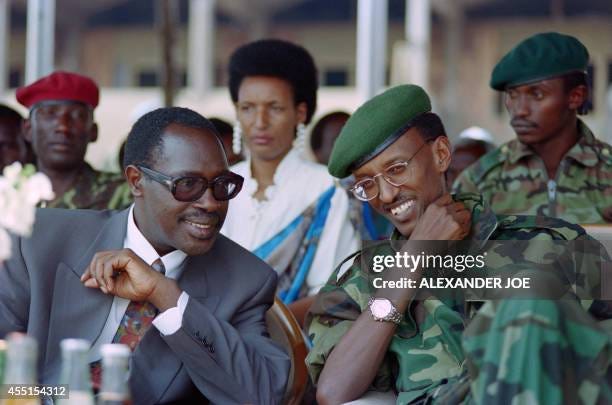

Following the the RPF's 1994 victory, a Government of National Unity was established to promote reconciliation. Kagame supported the appointment of Hutu to key positions, including Faustin Twagiramungu as Prime Minister and Pasteur Bizimungu as President to ease fears of Tutsi dominance. Despite this, Kagame was the Shadow President VP and Defense Minister.

While, 12 of 18 cabinet ministers were Hutu, the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Army dominated the military and police. At the local level, RPF appointed loyalists, with 117 out of 145 mayors were Tutsi. Over time, Kagame and the RPF consolidated power, as many Hutu leaders resigned, disappeared or fled. Kagame has served as Rwanda's President since his election in 2000, maintaining leadership ever since.

Rebuilding a Shattered Nation

Unity & Reconciliation

Kagame implemented a “One Rwanda” policy, abolishing Hutu/Tutsi labels and framing the genocide as a political, not ethnic, conflict. He highlighted that Hutu militias also killed tens of thousands of moderate Hutus, and that Hutu-Tutsi distinctions were originally castes, not ethnicities. The RPF promoted propaganda songs blaming European colonizers for divisions.

Justice: Gacaca Courts & The UN Tribunal

In November 1994, the UN established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), which indicted 93 genocidaires by 1995.

To address the ICTR’s slow progress, Gacaca courts tried 1.9 million Hutus domestically, with 65% found guilty. These community courts offered reduced sentences for repentance and reconciliation, though controversial for forgiving some low-level perpetrators. They aimed to balance justice and healing.

Economic Recovery and Attempted Liberalization

Kagame and Bizimungu liberalized the economy, privatized banks, slashed maximum tariffs from 100% to 40% and privatized some state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Key examples included selling Rwandatel (Telecom SOE) to Libya’s LAP Green Networks and Electrogaz to Germany’s Lahmeyer International, though the latter was renationalized due to poor service. Privatization had mixed results in Rwanda, so Kagame shifted focus to promoting government, military, and party-owned enterprises and attracting foreign investment rather than selling off state monopolies.

Agricultural Recovery

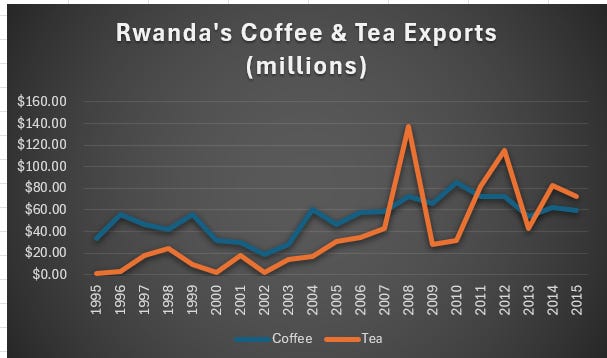

Kagame privatized tea & coffee factories and designated land near Kigali airport as an export processing zone to boost trade for agro-business. The tea and coffee marketing boards were reformed, shifting from paying farmers low wages to liberalizing prices. These boards also began offering affordable credit for fertilizers and agricultural training. While coffee exports saw modest growth, tea experienced a true export boom, soaring from just over $1 million in 1995 to over $100 million by the late 2000s.

Western Aid and Chinese Partnerships

Rwanda secured low-interest IMF loans ($65M+, 1998–2005) and World Bank grants ($200M+) for emergency programs. China played a pivotal role in rebuilding roads and buildings post-genocide.

Meanwhile, the World Bank provided low interest loans & grants to Rwanda in water, transportation, health, education, food security, and energy

Resettlement and Reintegration

The UN Joint Reintegration & Program Unit helped hundreds of thousands of families resettle in Rwanda. There was a massive influx of Rwandan Tutsi returning from Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya, Burundi, and Congo, while Hutu fled to the same countries, with many ending up in Congo’s Kivu region.

However, the rebuilding still had some issues.

The Kibeho Incident

When France withdrew from Rwanda’s Blue Zone, it left camps housing over 1 million displaced Rwandans. By February 1995, Operation Retour, a UN initiative, peacefully repatriated 700,000 people, but 250,000 remained in nine camps in Gikongoro, including Kibeho, which housed 80,000.

Kagame viewed Kibeho as a hub for extremists like the Interahamwe, while the UN saw displaced civilians. On April 18, 1995, violence erupted as RPF forces closed the camp. Hutu extremists reportedly attacked civilians who tried to comply with the RPF, and the RPF opened fire. The UN estimated 4,000 deaths, while Kagame’s government claimed 338—a figure widely disputed. The UN accused the RPF of attempting to cover up the massacre.

The event damaged Kagame’s reputation in the West. Western media called it a massacre, Hutu hardliners said 8K died and labeled it genocide, and the RPF suppressed discussion. Although Kagame allowed a UN investigation, mistrust of the UN deepened, especially with ongoing accusations of a “double genocide.” The massacre reinvigorated Hutu extremists, who regrouped in Congo and launched cross-border attacks, escalating the conflict.

Hutu refugees feared returning to Rwanda, citing alleged RPF atrocities in areas like Kibungo and Kigali, as detailed in the Gersony Report, which claimed 45,000 Hutus were killed. Kagame condemned revenge killings, and the RPF admitted isolated incidents but denied systematic targeting of Hutus. While some Hutu were in refugee camps in the blue zone, even more fled to Congo.

The Hutu flee to Congo

As the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) gained control in 1994, Hutu genocidaires (The Hutu Army, Hutu Power, and the Interahamwe) orchestrated a mass exodus into Zaire (now Congo). In its last broadcasts, Radio Mille Collines, spread fear and terror, warning of RPF “devils” bent on Hutu genocide. Led by local officials, entire Hutu villages decamped on foot, cars, bikes, and trucks, taking their belongings as they passed through the French safe zone into North & South Kivu in East Congo. The French did not arrest the genocidaires (like Colonel Bagosora) as their mandate was to remain neutral, thus French protected the organizers of the genocide. This influx destabilized Congo.

By 1995, between 1 to 2 million Hutu refugees, including genocidaires and the remnants of the Hutu-led government, established camps in North and South Kivu.

Needless to say Congo was not ready to assist a mass of Hutu refugees crammed in disease ridden camps without food or shelter. So Clinton air dropped air food to the Hutu refugees and raised $1M in a day for them.

Militarization and Exploitation of Aid

Camps in Lac Vert, Congo became hubs for extremist militias such as the RDR and FDLR, who exploited $800M in annual Western aid and acquired arms from Mobutu’s army to militarize and plan genocidal attacks on Rwanda. Extremists also targeted the Congolese Tutsi, called the Banyamulenge, further destabilizing the region.

Hutu genocidaire, Colonel Bagosora vowed to “wage a war that will be long and full of dead people until the minority Tutsi are finished and completely out of the country”. The Hutu Power brainwashed their Rwandan refugees for new recruits to bring their ranks from 30K to 50K.

The camps operated as self-sufficient enclaves, with over 82,000 businesses, including bars, restaurants, shops, and even cinemas. The refugee camps were so well stocked that Congolese came from miles away to shop at chez les Rwandais. Aid organizations unknowingly financed Hutu militias when the militias inflated refugee numbers, providing supplies, and funding transport, office supplies, and meeting places used for recruitment and operations. A shocking 66% of aid meant for Rwandan reconstruction was funneled to these camps, enriching the genocidal Hutu Power leaders.

Richard McCall, an administer for the Clinton administration described the camps as “an unfettered corridor for arms shipments for to the genocidaires”. Some aid groups stopped giving aid to the Hutus and left. Doctors Without Borders said “The situation has deteriorated to such an extent that it is now ethnically impossible to continue aiding and abetting the perpetrators of genocide.”

Despite the thriving camp economy, the influx of refugees created severe ethnic tensions. Hutu militias attacked the Banyamulenge (Formerly Rwandan Tutsi that have lived in Kivu, Congo since the 1800s, back when Kivu was under the influence of the Rwandan King), displacing tens of thousands Banyamulenge Tutsi and massacring thousands. Congolese militias, fueled by long-standing grievances, called themselves “autochtones”(natives) and joined the violence, attacking both Hutu genocidaires and Banyamulenge Tutsi communities.

While, Hutu genocidaires were killing Congolese Tutsi across Kivu, they also launched cross-border attacks in Rwanda. Kagame had to counterattack and neutralize the camps in Congo. Kagame pleaded to the West, to America, and the UN to help demilitarize the Congolese camps, but they were insensitive, especially after the Kibeho incident.

Mobutu’s Failed State

The camps were supposed to be policed by Mobutu, but Congo was a failed state. By 1995, Mobutu tried integrating the Hutu genocidaires into his army, but the process sparked mutinies.

Mobutu was facing waning support in his country and abroad. The IMF, World Bank, & the West cut him off in loans between 1993-1994 since he stole the funds and never completely executed the economic reforms which were conditions for the loans. The only way he could get aid would be having elections. Exploiting widespread anti-Tutsi sentiment to bolster his reelection bid and secure Western aid, he revoked citizenship from all Banyamulenge Tutsi.

Kagame’s Strategy

Kagame, Rwanda's Vice President, knew he needed to disrupt the camps to prevent a civil war. Some Hutu fighters were reintegrated if they surrendered, but many refugees who wanted to return home were killed by Hutu Power extremists. Kagame launched military operations to neutralize the camps, targeting militias while working to reintegrate peaceful Hutus into Rwandan society.

Due Mobutu’s tacit acceptance/inability to stop Hutu militias from killing Banyamulenge Tutsi and attacking Rwanda, and International Community’s inaction, Kagame felt he had to intervene.

Congo War 1, aka, “The Great Lakes Holocaust Part 1”

Kagame wasn’t alone in facing rebels operating from East Congo; Museveni of Uganda dealt with rebel groups (see my Uganda article for Museveni’s POV).

Kagame and Museveni sought a proxy to overthrow Mobutu, stabilize the borders, eliminate rebel groups, and secure access to Congo’s gold, diamonds, copper, and cobalt. Museveni brought in Laurent-Désiré Kabila, a Congolese rebel, warlord, and gold smuggler who had extra homes in Uganda, to topple Mobutu.

Museveni and Kagame backed Laurent Kabila for their own interests, helping him form the Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Congo (AFDL), which included Congolese Tutsi rebels. This alliance sparked the First Congo War, toppling Mobutu and killing 250,000 Congolese. Kabila took power, and 700,000 Rwandans, one of the largest and fastest repatriations in history, returned to Rwanda. However, many returning Hutu refugees were extremists, launching terrorist attacks in the late 1990s. In 1997, Hutu extremists killed thousands of Tutsi in Mudende, Rwanda.

Conclusion

The Tutsi genocide was a profound tragedy, but Kagame and his group of Tutsi exiles, the RPF, reclaimed their homeland and united Rwanda.

However, instability in the Great Lakes Region persisted. After the genocide, Hutu extremists fled to Congo, sparking the First Congo War, which claimed 250,000 lives. However, the Congo-Rwandan tensions are far from over—stay tuned for the thrilling conclusion in Part IV.

>Exploiting widespread anti-Tutsi sentiment to bolster his reelection bid and secure Western aid, he revoked citizenship from all Banyamulenge Tutsi.

The craziest thing is just how many times their legal status has changed in such a short period.

It's really hard for me to comprehend how those changes were not opposed on consistency grounds.

It is an interesting read; I like the backdrop that the struck-through words bring.