The Economic & Geopolitical History of Rwanda Part IV: Rwanda-Congo Issues & Kagame's Stewardship

Kagame: Half "Mr. Security", Half "Mr. Brand Marketer"

Intro:

Paul Kagame, Rwanda's president since 2000, is praised for transformative governance but faces criticism over alleged reliance on smuggled Congolese resources. This article examines his geopolitical and economic legacy.

Context:

Part I traces Rwanda’s history—from the traditional Rwandan Kingdom through German and then Belgian colonialism. The piece ends with Hutu dominance on the eve of independence.

Part II covers Hutu rule, Tutsi oppression, and the 1990s Rwandan Civil War.

Part III explores the Rwandan Genocide, post-genocide recovery, and the First Congo War. During that conflict, the army of Congolese President Mobutu, anti-Tutsi Mai-Mai militias, and Hutu genocidaires targeted Congolese Tutsi (Banyarwanda & Banyamulenge). Hutu militias also launched attacks on Rwanda from UN refugee camps in Congo. Kagame, alongside Museveni of Uganda and rebel leader Laurent Kabila, ousted Mobutu, setting the stage for Rwanda's involvement in Congo’s turbulent geopolitics.

Rwanda’s Geopolitics with Congo

The Banyarwanda and Banyamulenge

Understanding the origins and plight of the Banyarwanda and Banyamulenge (Bawn-ya-moo-len-geh)—collectively referred to as "Congolese Tutsi"—is crucial to the Rwanda-Congo conflict. They comprise:

Tutsi who migrated to Kivu, East Congo during the Rwandan Kingdom era in the early 1800s before colonialism.

Tutsi who moved from Belgian Rwanda or Burundi to work in mines in Belgian Congo.

Tutsi exiled during Rwanda's Hutu supremacist era.

Despite their long-standing presence, these communities have been viewed as foreigners by many Congolese. In 1972, Mobutu granted them citizenship, only to revoke it in 1981, heightening tensions in eastern Congo.

Second Congo war (1998-2003) Rwanda-Congo #2

The Kagame-Museveni-Kabila Alliance Falters

Initially, the Kagame-Museveni-Kabila alliance was strong, with Rwandan and Congolese Tutsi advisors wielding significant influence in Kabila's government. James Kabarebe, a former Tutsi officer of Kagame, served as the Congolese army's chief advisor. Kabila also promised citizenship to the Congolese Tutsi but failed to deliver.

Despite the alliance, Kabila failed to eliminate Hutu militias of the exiled Hutu Rwandan government. From July 1997 to January 1998, Hutu genocidaires collaborated with anti-Tutsi Mai-Mai militias and Burundian Hutu rebels, killing 5,000 Congolese Tutsi.

By 1998, Congolese resentment grew as Kabila was accused of being a puppet of Rwanda and Uganda, whose troops occupied eastern Congo to fight rebels and trade Congolese gold and diamonds. Anti-Tutsi sentiment surged, with Congolese Tutsi labeled as arrogant foreigners conspiring with Rwanda to "colonize" Congo. Anti-Congolese Tutsi lynchings erupted in North and South Kivu in East Congo, and Kabila capitalized on this nationalist fervor.

Anti-Tutsi Backlash and the Rift:

Wanting to avoid a potential coup, Kabila expelled Rwandan, Congolese Tutsi, and Ugandan troops and advisors, replacing them with loyalists and arming Hutu genocidaires. Kabila and his allies, including Foreign Minister Abdoulaye Yerodia Ndombasi, fueled anti-Tutsi pogroms. Ndombasi, dubbed “African Goebbels,” incited violence with inflammatory speeches, calling Congolese Tutsi “germs that must be methodically eradicated.” Kabila echoed this rhetoric on the radio, urging Congolese citizens to use machetes, spears, and even household tools to kill Banyamulenge Tutsi. Tutsi families who had lived in Congo for centuries were attacked, with one survivor poignantly stating, “Where do you want me to go? This is my home.”

Rwandan and Ugandan Intervention, A Regional War

With Kabila arming Hutu genocidaires and failing to curb cross-border attacks by Hutu rebel groups, Rwanda, Uganda, & Burundi invaded and launched their 2nd intervention, backing the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD), a Congolese Tutsi-led rebel group, to secure control of eastern Congo’s mineral resources, protect Congolese Tutsi, and counter rebels executing cross border attacks.

Kabila countered by rallying Congolese nationalism, framing the conflict as a fight against foreign domination. Rwanda almost ousted Kabila by flying men out to the capital to remove Kabila, but Kabila secured support from Angola, Zimbabwe, Namibia, and Chad. The war escalated into a continental war, with each faction pursuing political and economic gains.

Atrocities and Ceasefires

All sides have committed many atrocities. In 1999, the Lusaka Accord aimed to establish peace, calling for troop withdrawals, militia disarmament, and UN peacekeeping under MONUC (Mission de l'Organisation des Nations Unies en République démocratique du Congo), but was poorly enforced.

Rebel factions splintered as Museveni backed Jean-Pierre Bemba’s Movement for the Liberation of Congo (MLC), while Kagame continued supporting the RCD. Rivalries escalated into violent clashes between Ugandan and Rwandan forces in Kisangani, a diamond-rich city, in 2000.

As you can see from the map, Kisangani is so far from the Rwanda-Uganda-Congo border that this fight shattered their pretense that their presence in Eastern Congo was for self-defense. Instead, the Congolese people and the West saw Museveni & Kagame as plunderers and exploiters. The UN told Rwanda and Uganda to leave. Laurent Kabila was then killed by his bodyguard in 2001.

Plundering Congo’s Resources

During this war, Rwanda and Uganda entrenched their presence in eastern Congo, smuggling Congo’s gold, diamonds, timber, and coltan. Rwanda’s export profile shifted significantly during the war, with minerals like coltan and tin ore overtaking traditional exports like coffee. See chart below:

The Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) managed Congolese minerals using enterprises like Rwanda Metals. A UN panel estimated that coltan production in eastern Congo was under RPA control, with minerals flown out from airstrips near mines.

Global Condemnation and Humanitarian Crisis

Outraged by the plunder and violence, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan urged sanctions against Rwanda and Uganda. Kofi’s 2001 UN report accused both nations, along with Burundi, of looting Congo’s resources. The war caused over 5 million deaths, primarily from disease, starvation, and state collapse, marking it as the deadliest conflict since World War II.

Attempts at Peace

In 2001, Joseph Kabila, Laurent’s son took over Congo in a questionable fashion. Then in 2002, Thabo Mbeki of South Africa brokered a peace agreement in Pretoria between Congo & Rwanda, where Congo agreed to disarm Hutu militias and extradite some genocidaires to Rwanda.

However, Kabila’s cooperation was limited, and Hutu rebel groups continued operating in eastern Congo. Despite these efforts, local militias, anti-Tutsi Mai-Mai groups, and Congolese Tutsi rebels continued fighting in Kivu and Ituri in East Congo, using resources to fuel their conflict.

Tripartite Agreement and Aftermath

In 2004, Rwanda, Uganda, and Congo signed a tripartite agreement with UN support to pressure Hutu militias (FDLR) to disband. Rwanda faced international criticism and temporarily lost foreign aid for its actions in Congo.

The Kivu Conflict in East Congo (2004-2009), Rwanda-Congo #3

After Rwanda’s official withdrawal, violence persisted in eastern Congo as conflicts escalated between Congolese Tutsi, anti-Tutsi Mai-Mai militias, and Hutu genocidaires. Laurent Nkunda, a Congolese Tutsi warlord, led the National Congress for the Defense of the People (CNDP), a 6,000-strong rebel group. Using kidnapped child soldiers, the CNDP seized cities like Goma, displacing nearly 2 million people in North Kivu.

Nkunda aimed to eliminate Hutu militias and had ambitions of controlling the entire Congolese state. His Tutsi identity led to widespread suspicions that Rwanda, under Paul Kagame, backed his rebellion—allegations Kagame denied, but the UN Security Council believed was true. The 90K-strong Congolese army, poorly trained and corrupt, struggled to contain the CNDP, prompting the UN to deploy 17,000 peacekeepers under MONUC again in 2008.

The 2009 Kagame-Kabila Deal

Facing international pressure, Kagame and Joseph Kabila struck a deal in 2009: Rwanda arrested Nkunda after he crossed into Rwandan territory, while the two governments launched a joint offensive against the Hutu FDLR. While many Hutu militia members were defeated, others escaped and regrouped in South Kivu, killing hundreds of Congolese in the process. Also, in March 2009, a peace agreement was reached to integrate the Congolese Tutsi rebels in the Congolese army. This should have ended the issue of the Congolese Tutsi once and for all. However…

The Rise of M23 Rebellion(2012-2013): Rwanda-Congo #4

In 2012, the March 23 Movement (M23), led by Congolese Tutsi warlord Bosco Ntaganda, emerged after a mutiny within the Congolese army. Named after the failed 2009 peace deal, M23 accused the Congolese government of supporting the Hutu genocidaires (FDLR) and launched a rebellion to protect Congolese Tutsi. Despite its small size (around 1,500 fighters), M23 outmaneuvered the corrupt Congolese military.

Rebellion and Accusations

M23 seized the big Congolese city of Goma, displacing nearly 500K people and committing widespread atrocities, including rape, child recruitment, and illegal mining. The UN accused Rwanda and Uganda of supporting M23 to exploit Congo’s minerals and implicated Rwandan military leaders Charles Kayonga and James Kabarebe. Rwanda and Uganda denied the accusations. But international pressure, including Western aid cuts led by Obama & Cameron, intensified scrutiny on Kagame’s government.

Defeat and Aftermath

In 2013, UN-backed forces defeated M23, forcing its fighters to flee to Rwanda and Uganda, where their weapons were confiscated and the group temporarily disbanded. Bosco Ntaganda surrendered to the ICC, facing war crimes charges, but violence persisted between the different groups in East Congo.

Brief Rapprochement between Congo & Rwanda (2019-2021)

Between 2019 and 2021, Congo and Rwanda made efforts to mend relations, signing three bilateral trade agreements and collaborating to combat the Hutu rebels. The cooperation followed a deadly Hutu rebel attack on Rwanda that killed 14 people and destroyed villages. In retaliation, the Congolese military killed a Hutu rebel leader, Sylvestre Mudacumura.

However, the rapprochement did little to resolve deeper issues….

M23 Issue Round 2, Congo-Rwanda #5 (2021-Present)

In November 2021, M23 reemerged, citing persecution and attacks on Congolese Tutsi by militias like the Mai-Mai and Hutu rebels. Genocidal rhetoric against the Congolese Tutsi spread again in North and South Kivu, with accusations that they were agents of Uganda’s Museveni or Rwanda’s Kagame. Facing ongoing violence, M23 launched a new offensive.

M23's Actions and Regional Tensions

M23 has committed massacres in Congo and seized key areas like Rubaya (April 2024), home to tantalum mines supplying 15% of the world’s coltan, which funds their operations ($800K a month). Congo’s corrupt & inefficient army partnered with local militias, such as the Wazalendo ("patriots"), but M23 conquered Goma again in January 26th 2025. In response, the Congolese government severed all diplomatic ties with Rwanda, calling it a “declaration of war”. This is an escalation from Rwanda & Congo’s previous cross border clashes (i.e. Rwanda shooting down a Congolese fighter jet in 2023).

Regional and International Involvement

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) & East African Community deployed over 10K soldiers from South Africa, Tanzania, Burundi, Kenya, Uganda, and more to protect Congo from M23. But SADC troops were getting murdered by M23. Reports from Congo, the United States’ State Department, and the UN suggested that M23 receives arms and support from Rwanda, and possibly Uganda, with 4K of Rwanda’s troops allegedly aiding M23 despite Kagame’s denials. The UN, EU, and US blame Rwanda, while Congo’s President Félix Tshisekedi went further and accused Kagame of being “Hitler” and a "warmonger" exploiting Congo’s minerals.

Failed Ceasefires and Persisting Conflict

Efforts to broker peace, including a 2024 Biden Administration & African Union mediated ceasefire, have repeatedly failed. Kagame, while denying official involvement, insists that the Congolese government must protect the Congolese Tutsi from genocide and eradicate the genocidal Hutu rebels (FDLR) that Congo uses as military proxies. Tshisekedi denies this, but the FDLR has assisted the Congo’s fight against M23.

The USA and EU have sanctioned individuals from Hutu Rebel groups, M23, and the Rwandan Army (excluding Kagame), freezing their U.S. dollar denominated assets through the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC).

After UN Security Council Resolution 2773 (21 Feb 2025) formally condemned Rwanda’s support for M23, a U.S.-brokered peace agreement was signed in Washington on 27 June 2025 under President Trump’s mediation. Although this deal commits both governments to withdraw troops and end backing for armed groups, its success hinges on enforcement—and only time will tell whether another accord may be needed down the road.

Geopolitics with Other States

Rwanda joined the East African Federation in 2007, but integration has been challenging (See my Uganda article for more).

Besides joining the East African Federation, Kagame aims to establish Rwanda as a reliable military force in Africa, promoting “African Solutions to African Problems.”

Military Engagements in CAR and Mozambique

Rwanda’s military presence in Central African Republic and Mozambique reflects Kagame’s regional ambitions. In CAR, Rwandan troops, allied with the national army and Russian Wagner Group, helped combat Muslim rebels. In return, Rwandan miners operate in a joint gold and diamond venture, OKO Africa, with CAR. There’s also Rwandan bars and restaurants in the country.

In Mozambique, the EU has committed €40 million through the European Peace Facility to support Rwandan forces combating Islamic State insurgents who have been disrupting TotalEnergies’ (a French oil firm) liquefied natural gas projects in Cabo Delgado.

Meanwhile, Crystal Ventures—Rwanda’s state-owned investment arm—has poured capital into Mozambique’s mining, security, and construction sectors.

Economics

Kagame's Leadership and Economic Model

Paul Kagame, often labeled an "enlightened autocrat," has remained in power through elections in 2000, 2003, 2010, 2017, and 2024. Opposition figures are suppressed, as Kagame believes that at Rwanda’s current stage, the Rwanda’s true enemy should be poverty, and not opposing political parties.

It’s not widely known, but Rwanda is still poorer than most African countries due to being less urbanized than most African nations (Rwanda is 82% rural compared to Sub Saharan Africa’s 57% average). Rwanda’s donor aid adds up to ~75% of Rwanda’s government spending, which is roughly $1B.

The average Rwandan makes $1K a year ($3300 at purchasing power parity). At purchasing power parity, Rwanda is far poorer than a Nigerian, Kenyan, or Senegalese (for now) but the average Rwandan is still richer than a Ugandan, Burkinabe, or an Ethiopian.

The reason some people don’t think of Rwanda as a poor country is due to Rwanda’s

1. Fast growth

2. Financial prudence

3. Masterful Brand Strategy

4. Low corruption & effective governance

Fast Growth:

In 2003, Rwanda's per capita income was $250 at market exchange rates. By 2013, it grew to $710 (11% Compound Annual Growth Rate - CAGR), and by 2023, reached ~$1K (3.4% CAGR). Unlike other African countries, which saw economic stagnation or decline after 2013, Rwanda maintained steady, albeit, slower growth. See table below:

Rwanda is fast growing, but its growing from a very low base. To put in perspective, even though the oil-state, Angola, has on average declined nearly 3% every year from 2013 to 2023 due to the post 2014 oil price collapse, the average Angolan still makes more than 2x the average Rwandan.

Financial Prudence:

Unlike most African countries, Rwanda hasn’t needed an IMF emergency loan since 2005. Also, Rwanda benefited from the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) and Multilateral Debt Relief Initiatives, reducing its foreign debt from $1.5 billion in 2005 to $0.4 billion in 2006—a 75% write-off.

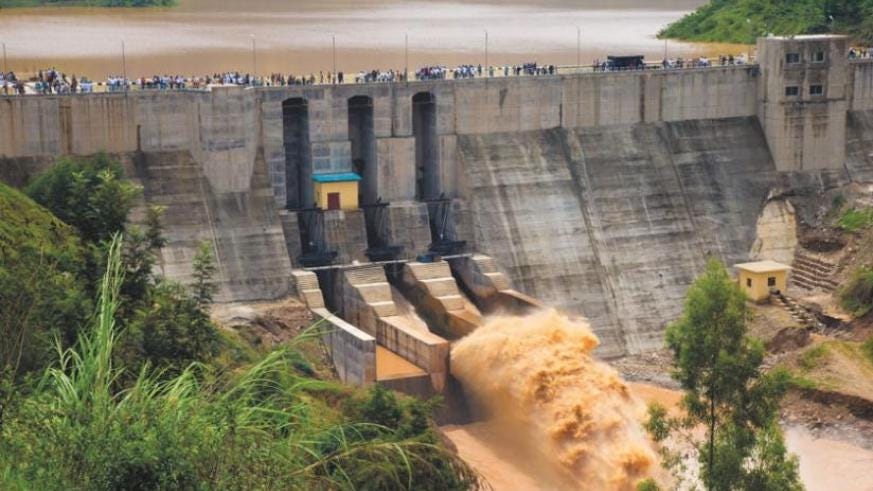

Kagame sought to showcase Rwanda’s financial stability to international investors by entering the Eurobond market in 2013. Rwanda raised $400M (10-year term at 6.6% interest) to fund RwandaAir and the Nyabarongo hydropower plant. In 2021, the bond was refinanced with a $620M Eurobond (10-year term at 5.5%), repaying the original bond and securing an additional $220M for development. As of 2025, Rwanda holds a B+ credit rating, the 9th highest in Sub-Saharan Africa, though still classified as high risk. Rwanda has also secured loans from India ($100M) and China ($33M) via export-import banks to support growth.

Branding & Tourism: Rwanda’s crown Jewel

Although two-thirds of Rwandans are subsistence farmers and a third of children under five face chronic malnutrition supported by the UN World Food Program, Rwanda's global image is shaped by Kigali, where under 10% of the population resides. This perception shift reflects the success of the Rwanda Development Board’s Visit Rwanda campaign, which positions the country as a stable, desirable destination.

The disconnect between Rwanda’s perception and reality highlights how successful the development board’s branding campaign has been. In order to attract tourism, the country needs a strong image. Then eventually, the living standards will match the brand.

Tourism, Rwanda’s 2nd largest foreign exchange earner, revolves around attractions like Volcanoes National Park and Akagera. Sponsorships with Arsenal, PSG, and Bayern Munich enhance branding, while Kigali, Africa’s #2 convention hub after Cape Town, hosts global events like the FIFA Congress and Commonwealth Heads Meeting. Despite this success, Rwanda’s foreign exchange earnings heavily depend on smuggled Congolese gold.

Low Corruption & Effective Governance:

The country boasts low corruption, decent rule of law, and effective governance indicators.

FDI (Foreign direct investment)

Strong governance indicators, financial prudence, and branding has incredible second order effects. As a result, Rwanda’s successful marketing campaign as the “Singapore of Africa” helped Rwanda receive a higher proportion of FDI than most Sub-Saharan African countries. However, its a long way before it reaches Singapore levels.

Notable Rwandan investments include:

Nuances on the Rwandan Economy

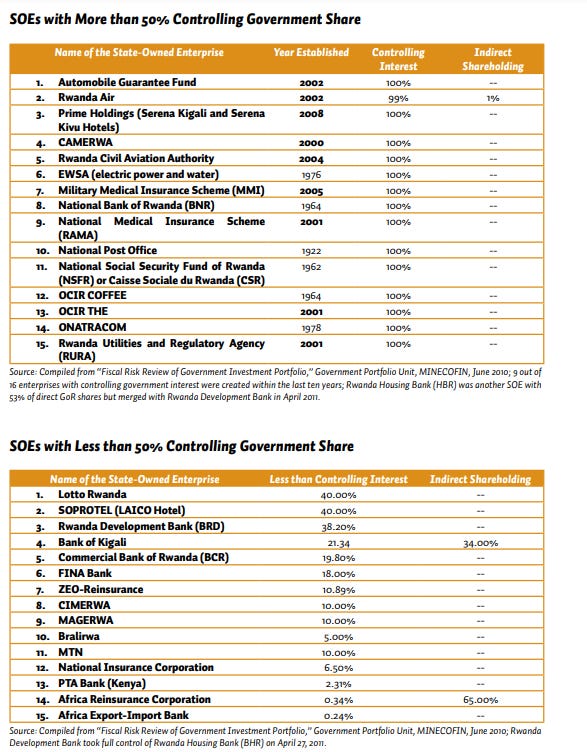

Like most developing countries, Rwanda’s economy is 75% informal. Rwanda blends economic models: besides private companies, Rwanda has military-owned enterprises like Egypt, Pakistan, or Uganda, party-owned enterprises akin to pre-1990s Taiwan & Eritrea, and state-owned enterprises targeting FDI for joint ventures, similar to Vietnam or Singapore.

Party/Government/Military Enterprises in Rwanda

Kagame initially embraced neoliberal privatization but then walked it back in the early 2000s to create party-owned enterprises through the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF). These enterprises supplement limited tax revenue and are managed by RPF-appointed elites, controlling major sectors like real estate, agro-processing, and manufacturing.

The biggest example is Rwanda’s Crystal Ventures (formerly Tri-Star) RPF’s investment arm, managing:

Inyange Industries (beverages and dairy)

Nyarutarama Property Developers (real estate)

ISCO Security (security services)

EAGI (granite processing)

Crystal Ventures accounts for about 10% of Rwanda's GDP.

The Rwandan military owns an investment arm called Horizon Group, insurance, banking and other firms. Then there’s private firms like the Rwandan Investment Group which is influenced by the RPF, holding stakes in state-owned hotels and manufacturing.

Also like Singapore, the Rwandan government has substantial ownership in many sectors of the economy. See table below for industries where the Rwandan government has a majority and minority stake:

Is Rwanda’s Growth due to Brand or Mineral Smuggling?

As mentioned, Rwanda has and still does re-export and smuggle Congolese minerals. Rwanda officially exports more gold, tin, and coltan than Congo even though Rwanda barely produces those minerals, most of it comes from Congo.

However, as you can see from the export chart below, since 2008, Rwanda now relies more on services (Tourism, travel, & logistics), than smuggling Congolese gold & rare earths.

Conclusion

Despite being a largely informal agrarian economy, Rwanda has developed a unique formal sector blending elements of pre-1990 Taiwan, Pakistan, and Singapore. Situated in a geopolitically volatile region, its strong branding offers hope for graduating to lower-middle-income status by 2030, following the path of that over 20 Sub-Saharan nations already accomplished.

Fantastic article as usual Yaw, thanks for sharing.

Great article! Amazing job in situating the historical(and present) involvement of Rwanda in the ongoing conflict and highlighting the motivations behind it!