Three Worlds, One Region: The Igbo, Yoruba, and Edo of Medieval Southern Nigeria

Empires, Priest-Kings, and Cavalry: The Rise and Struggles of Southern Nigeria (1100–1560)

Welcome back! This is Part IV of my remastered series on Nigeria.

Part I traced Nigeria's foundations from 1000 BC to 1100 AD, introducing the Nok ironworkers, early Hausa settlements, the Kanem-Bornu, Yoruba, and Igbo. The article also gave a brief overview of modern Nigeria.

Part II & Part III focused on Northern Nigeria from 1100 to 1900 AD, covering the Trans-Saharan slave trade, the rise of Islam in Northern Nigeria, Hausa city-states, and the Sokoto Caliphate.

Today, we turn south to explore what was happening in Southern Nigeria between 1100 and 1560 AD, focusing on three major civilizations: the Nri (Igbo), Ife & Oyo (Yoruba), and Benin (Edo).

The Igbos of Nri: Sacred Authority in a Stateless World

The Igbos of Nri, centered around farming communities near the Anambra River, was known for its ritualistic culture. The civilization was centered on yam cultivation, palm oil production, livestock, and blacksmithing.

Picture this: During yam harvest season, farmers would bring their finest tubers before the Eze Nri — a priest-king who wielded no sword or army, but held immense “spiritual power”.

When conflicts erupted between villages—perhaps over land disputes or accusations of witchcraft—messengers would travel for days to reach the Eze Nri's compound. There, surrounded by sacred groves and ritual objects, he would perform ceremonies involving elephant tusks, kola nuts, and palm wine. His word could “remove curses”, exile individuals from their communities or, conversely, welcome them back into the fold of acceptable society.

Nri organized itself with village elder councils and had strong women's political institutions, such as the Umuada (daughters of the lineage) and Ilimmadụotu (wives’ council).

Unlike the Edo and Yoruba, the Igbo lived in highly decentralized, acephalous (headless) villages. When the British arrived in the 1800s, they lumped people from Nri, Arochukwu, Onitsha, and others into the umbrella term "Igbo," based on their shared language (though differing dialects).

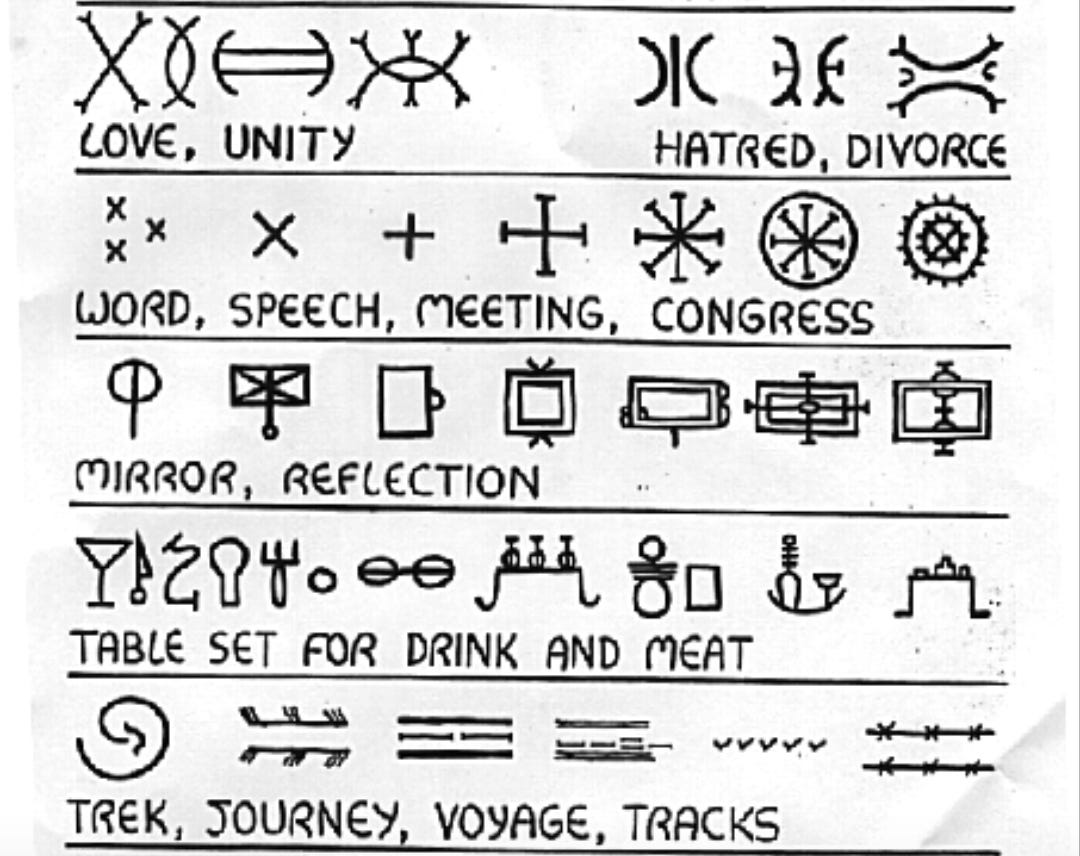

Nri was pre-literate, but some Igbo in secret societies had a secret script called Nsibidi. However, your mileage may vary on whether you consider Nsibidi written word or not. It was a symbolic script, not a full alphabet or syllabary — ideographic/pictographic, like early Chinese or Egyptian scripts.

The Yoruba: From Sacred Cities to Cavalry States

Unlike the Igbo, the Yoruba developed city-states and kingdoms—such as Ife, Owu, and Ijebu—with structured monarchies led by Obas and supported by royal councils. Though the Yoruba were also pre-literate, their elite preserved knowledge through oral traditions, including praise poetry, court historians, and ritual specialists.

By the 15th century, Arabic literacy began seeping into Northern Yorubaland. Muslim clerics and merchants from Hausaland and Nupe introduced Ajami—local language written in Arabic script. Cities like Ilorin and Iseyin developed literate Muslim clerical & merchant classes by the 17th–18th centuries.

The term “Yoruba” was not originally used by the people themselves. It was a label popularized by Sahelian African Islamic scholars —Hausa, Songhai, & Tuareg people— to describe the people of the Oyo Kingdom. European colonizers later expanded the term to include every Southwest African in that region who spoke the same language of that Kingdom.

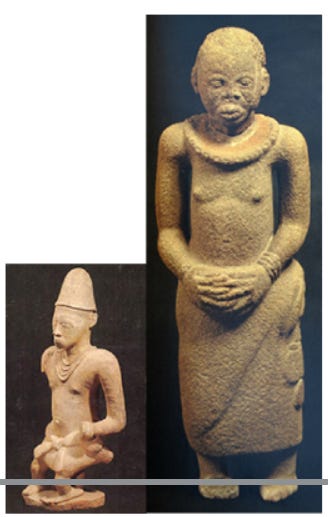

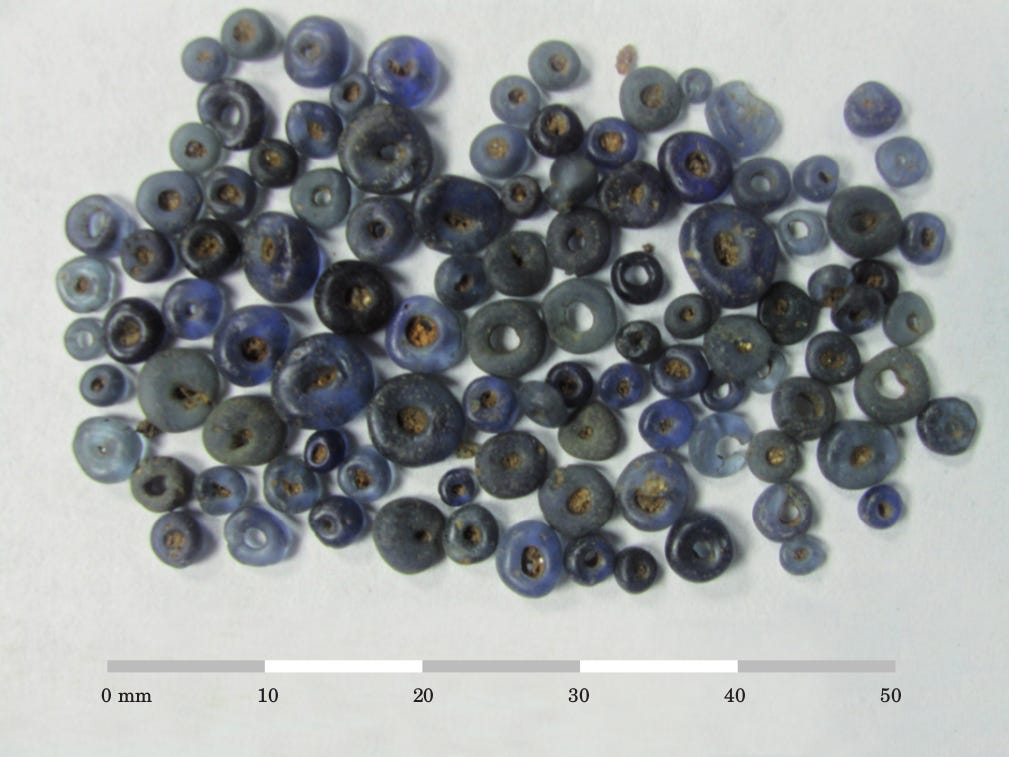

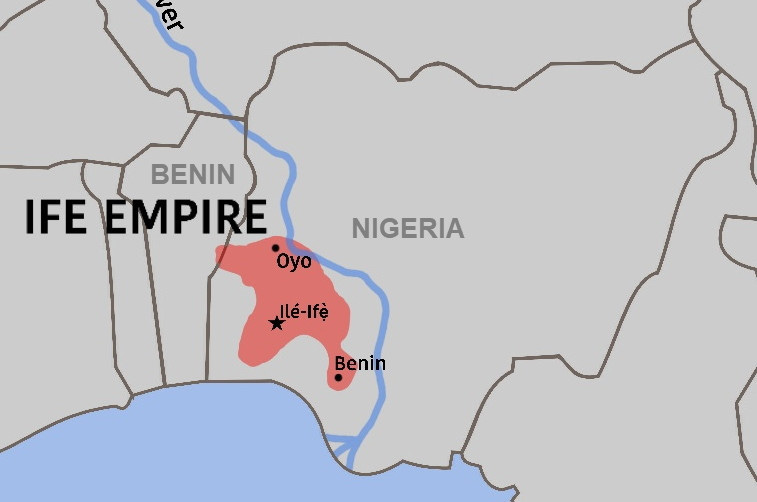

Around the 11th century, the Yoruba city-state of Ilé-Ifẹ̀ (or “House of Ife”) emerged as a spiritual and political center, known for its bronze sculptures, glass beads, and divine monarchy. It engaged in regional trade with Hausa and Sahelian merchants, exchanging beads and ivory for northern goods like salt and cloth. The Yoruba claim Ife was founded by a legendary man named Oduduwa.

Yoruba oral tradition tells of Oduduwa’s son, Ọ̀rànmíyàn, a legendary warrior-prince who expanded Ife's reach and supposedly founded Oyo. He became a cultural bridge between Ife and other Yoruba polities.

Not all Yoruba-speaking polities bowed to Ifẹ̀’s rule. Coalitions like Idoko and Ugbo actively resisted Ifẹ̀’s growing dominance—and were ultimately crushed by Ife and became vassals.

But Ife supremacy didn’t last.

One of Ifẹ̀’s allies—and later, rivals—was the kingdom of Owu, the first Yoruba polity to build a cavalry.

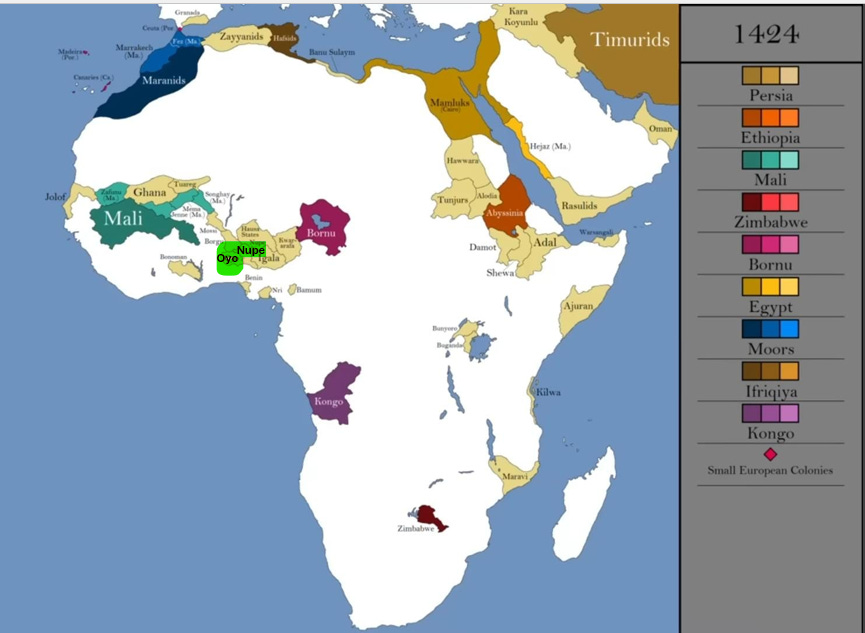

Owu traded iron and cloth with African peoples like the Mossi, Songhai, and Mande, acquiring horses (which were like the drones of today). In the 13th century, Owu conquered Oyo and Ilá, becoming a serious threat.

As Owu expanded, Ifẹ̀ spiraled into civil war due to a succession crisis. But out of the chaos emerged Ọbalúfọ̀n II, a warrior king who crushed his rivals and took control of Ife.

As Owu marched toward Ifẹ̀, Obalufon II aligned with King of Oyo, which was eager to free itself from Owu's domination. The Ife and Oyo city-states smashed Owu and absorbed its former vassals.

But just as the Ifẹ̀-Ọ̀yọ́ alliance hit its stride, a new threat emerged: the Nupe.

The Nupe used to be a bunch of fragmented villages. But the Nupe banded together to make a slave raiding confederacy. Positioned near the horse-riding Sahelian polities like Kanem-Bornu, Tuareg, and Hausa states, they traded war captives for horses. They also ran plantation economies, fueled by enslaved labor.

With slaves, the Nupe had discovered the deadly equation that would dominate West African politics for centuries: horses plus raids equals slaves, and slaves equals more horses. This was the “Horse-Slave exchange” in Middlebelt Nigeria.

Nupe horsemen thundered south, striking Yoruba towns like lightning. They would surround a settlement at dawn, capture everyone they could, and disappear before organized resistance could form. The captives were marched north to markets in Hausaland, where they were exchanged for fresh horses. It was a business model that required constant warfare. Horses couldn’t survive long in lower-middle belt Nigeria due to the blood sucking tse-tse fly. Tse-tse fly are a vector for trypanosomiasis infections, killing horses (and people) too.

This led to a constant cycle of raiding villages, capturing slaves, selling slaves for horses for a short while before quickly re-stocking horse supply.

By the 1400s, Ife was in a crisis due to droughts, epidemic diseases, and relentless attacks by the Nupe cavalry. Even the King, Obalufon II died of infectious disease. Due to these issues, Yoruba started mass migrating out of Ife.

Without Ife protecting its vassals like Upper Osun, Ibolo, Okun, and others, they fell into disarray as well. All of them were raided constantly by the Nupe cavalrymen who also took their territory. Polities that were under Ife’s thumb like Benin, left the orbit.

With Ife weakened, Oyo became the main Yoruba city-state. However, Oyo constantly had to defend itself from the slave raiding Nupe horsebacks.

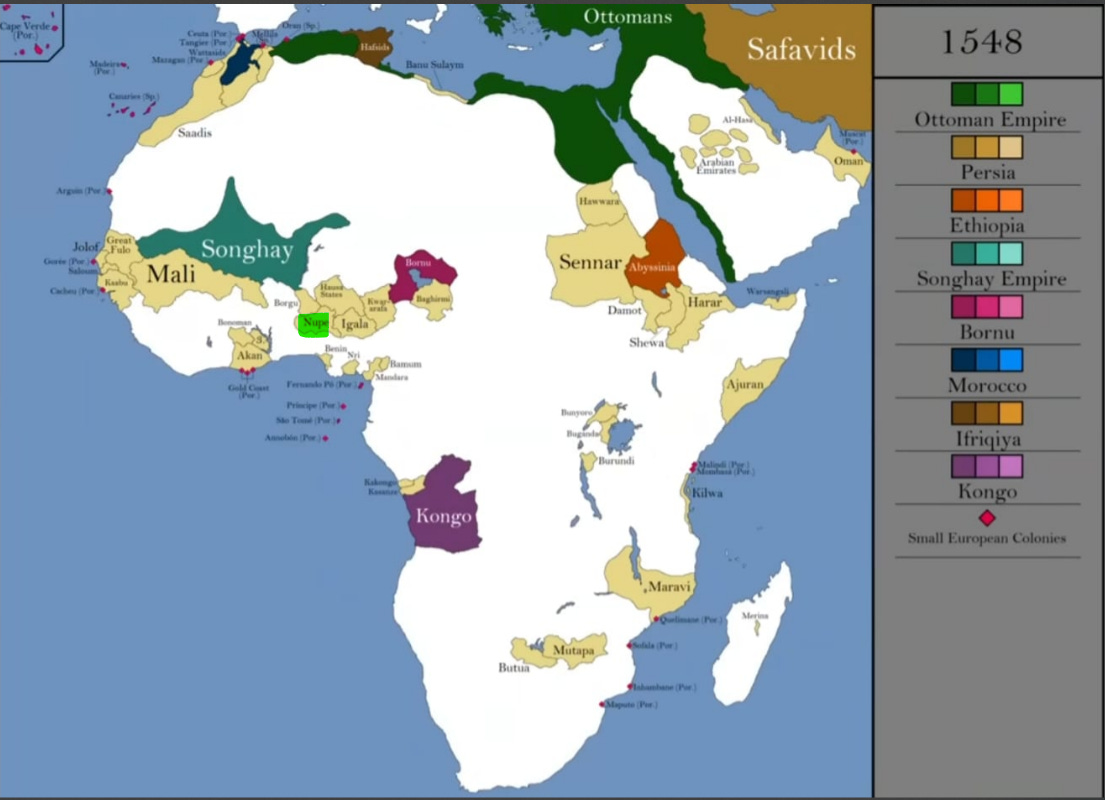

By 1500s, Nupe sacked Oyo, and conquered the Yoruba briefly.

The Alafins (Yoruba Kings) of Oyo fled, regrouped, and adopted the same horse-based raiding model. Oyo began to rebuild in the late 1500s by raiding villages and trading slaves to Songhai and Mossi for horses. In effect, West Africa’s Middle Belt became a grinding ground of two rival raiding systems: Oyo in the west vs. Nupe in the east.

Meanwhile, along the coasts, Portugal traded with Ijebu Yoruba in a coastal settlement and lagoon area that they named “Lagos”.

Oyo would eventually rise again like a phoenix—but that’s a story for the 17th century. Let’s dive deeper into the Edo of Benin.

The Edo of Benin: The Africans who met Europe

Unlike the fragmented Igbo and embattled Yoruba, the Edo of Benin had a centralized monarchy and early European contact, giving us richer documentation from European writings. Though pre-literate, Benin recorded its history through bronze plaques, ivory carvings, and oral historians.

Ogiso, Benin’s Proto-History

According to Edo oral tradition, the Ogiso dynasty once ruled Benin with paramount chiefs/kings—and occasionally queens—but collapsed in the 1100s due to misrule and a succession crisis. In the aftermath, power shifted to the Uzama (council of chiefs), who governed collectively and elected a paramount leader rather than relying on royal bloodlines.

But rule by chiefs soon unraveled. According to traditional Oral historian, Chief J.U. Egharevba, chief rule failed because one of the paramount chiefs tried to make his son the King instead of letting the Uzama appoint the next chief. This sparked unrest. As tensions grew, the Uzama sought legitimacy from the powerful Ooni of Ife, spiritual leader of the Yoruba. The Ooni sent his legendary son, Oranmiyan, to rule. He stayed briefly, fathered a son with an Edo woman, and returned to Ife.

The Benin Kingdom, a vassal of Ife

That son (who is real), Eweka, became the first Oba (Sacred king) of Benin, founding a new dynasty that balanced royal authority with Uzama counsel, ushering in a more centralized monarchy.

For generations after its founding, Benin's Obas ruled under the shadow of the Uzama chiefs. That changed in the 13th century, when Oba Ewedo broke their grip on power. He moved the royal palace from Usama, the chiefs’ stronghold, to Ubini—the heart of what would become Benin City—and established an absolute monarchy.

Though Ewedo centralized authority, tension lingered. Oral tradition recounts occasional power struggles: Oba Ohen was reportedly stoned to death for killing a senior chief, and his son clashed with the Uzama repeatedly. Benin became a vassal of the Yoruba city state-Ife. But that all changed with a dynastic succession dispute in the 1400s.

Fratricidal Rebirth

In the 1400s, Benin had a bloody dynastic dispute that erupted into a civil war. Oba Ohen died without a chosen successor. Many princes fought for the throne with the backing of a palace chief. A King was announced, but an exiled prince named Ewuare stormed and burned Benin City to kill his brother and take over. We can think of this as a “violent rebirth” because Oba Ewuare was pretty great. He was even called “Ewuare the Great”.

Oba Ewuare the Great (r. 1440–1473) expanded the city and the state. Ewuare came to power right when Ife and its vassals were declining from drought and disease. He renamed the capital Ubini to Edo, imposed royal authority over surrounding towns, and led military campaigns that subjugated parts of the Yoruba and western Igbo world.

Before him, the monarchy’s reach barely extended beyond the Oguola Moat, enclosing a loose federation of settlements. Ewuare changed that. He introduced urban planning: broad avenues, administrative divisions, and concentric moats and walls that separated the king from his subjects—physically and politically. The walls and moats were known as the Benin Earthworks—stretching over 10,000 KM, often cited as the second-largest man-made structure on Earth after the Great Wall of China.

Ewuare’s conquests created a tribute-based economy. Subject towns sent goods and captives to Benin and the Oba imposed tolls on trade routes.

The conquest of villages and towns continued with Ewuare’s son Ozolua. Ozolua tried conquering the Yoruba Oyo but failed at a border clash. Ozolua also met the Portuguese in the 1470s.

Portugal’s Slaves-for-Gold Circuit

Between 1469 and 1475, Portuguese merchant Fernao Gomes held a royal monopoly over West African trade. The Portuguese King wanted him to find the legendary African/Indian Christian King “Prester John”, but they didn’t find him. Instead, his sailors found African gold.

The sailors reached the “Costa de Mina” (Coast of the Mines” or Gold Coast in modern day Southern coastal Ghana) by 1471.

In the Gold Coast, they met Fante merchants who had plenty of gold dust.

When the Portuguese wanted to buy gold from the Fante merchants, the merchants demanded to be compensated in slaves since slaves were needed to mine the gold.

The Portuguese couldn’t conduct raids in the African interior due to deadly diseases that killed European explorers. So, Portuguese ships began sailing east. toward the Niger Delta.

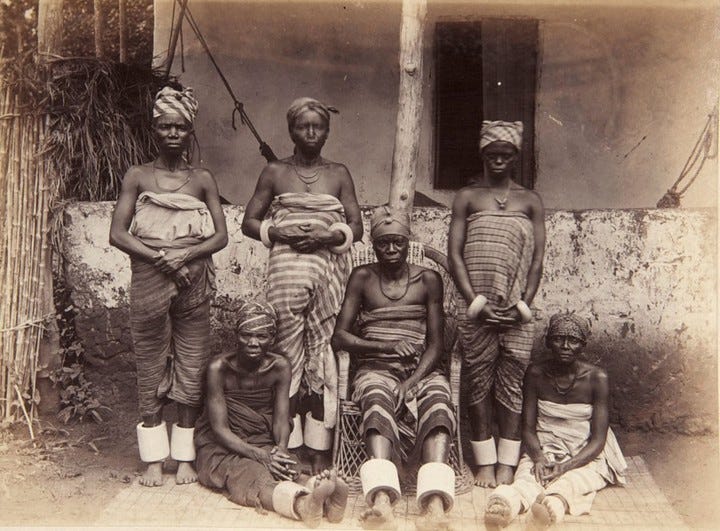

The Portuguese sailors described encounters with "pirates"—likely referring to the Ijo, Sobo, and Itsekiri fishermen people of the Niger Delta swamps. The Portuguese made trade deals with these Coastal African chiefs. The Portuguese traded textiles, iron weapons, and brass with them, and in return, these people will sell kidnapped Africans that they had land disputes with anyways. The Ijo, Sobo, and Itsekiri raided Edo villages at the fringes of the Benin Kingdom. The captives were then sold to Fante merchants in modern-day Ghana, in exchange for gold. In that first mission, the Portuguese grabbed 400 slaves for the Fante.

This was the 1st European-West African Slave Trade, before Portugal grabbed Brazil and wanted to ship Africans to the Americas.

As part of this vision, the Portuguese King commissioned the construction of São Jorge da Mina (Elmina Castle) in present-day Ghana and styled himself “Lord of Guinea”—the so-called "King of Black Africa."

The Elmina Castle in the Gold Coast, served as “trade house” where the Portuguese and the Akan set up exchange rates between people & gold. In addition, expeditions under Diogo Cão explored the Congo and Angola; and the Portuguese captured the virtually uninhabited island of São Tomé; and envoys were dispatched to rulers across West Africa. In Kongo, the Portuguese managed to convert King Nzinga a Nkuwu into Catholicism and change his name to João I.

With a permanent base at Elmina, the Portuguese needed a steady supply of slaves to exchange for gold. Unimpressed with the Ijo and Iwere’s capacity to deliver captives at scale, the Portuguese pushed further along the coast. In 1486, João Afonso d’Aveiro established contact in the rainforest zone where the Kingdom of Benin dwelled.

Benin & The Portuguese

When the Portuguese first reached Ughoton, the river port of the Benin Kingdom, they were welcomed by a local Edo chief. From there, he trekked four days inland to Benin City, where he met Oba Ozolua, the warrior king who ruled from 1483 to 1504.

On the way there, d’Aveiro and his crew were struck by how organized and sophisticated the Edo realm was—especially compared to the swamp-dwelling Ijo and Iwere communities further east. They later compared Benin City to Florence, Madrid, and Antwerp—a sign of the kingdom’s great urban planning.

Ozolua received the Portuguese with ceremony and responded in kind: he appointed an ambassador— the Ohen-Okun (Sea Chief) of Ughoton—to travel to Lisbon, symbolizing Benin’s openness to diplomacy. This marked one of the earliest recorded diplomatic exchanges between a West African kingdom and a European power.

By 1490, Benin and Portugal had formed a limited alliance. The Oba sought weapons and exotic goods. The Portuguese sought goods, Christian converts, and slaves.

Benin didn’t really like selling slaves. Between 1487-1507, Benin only sold 250 war captives. Luckily, Benin had other goods they could sell as well. You see Portugal loved peppers from India and Benin produced two valuable kinds: Malagueta and Guinea pepper. When Portuguese envoy Afonso d’Aveiro brought samples to Antwerp and other European markets, the African peppers sold nearly as well as its Asian rivals.

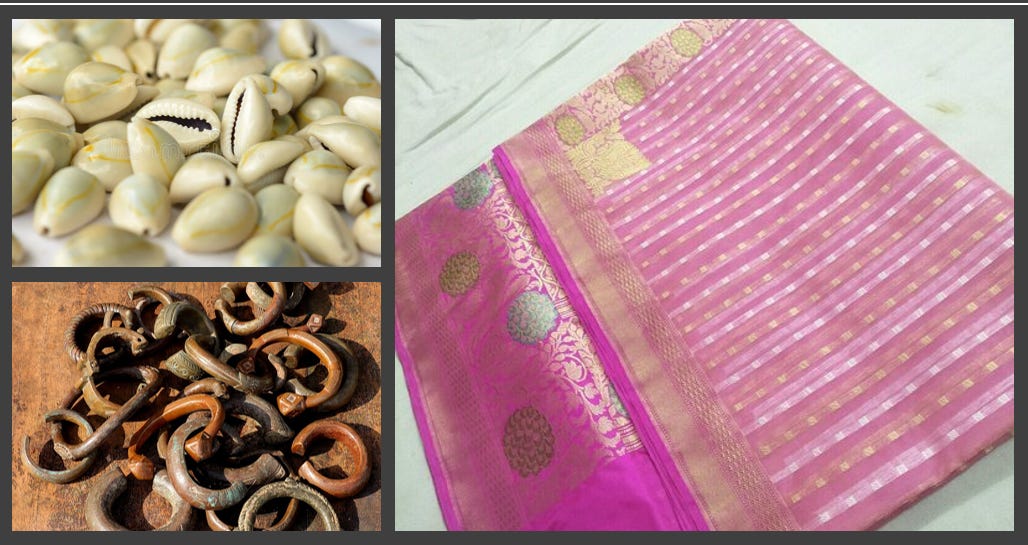

But pepper trade in Benin was no free-for-all. The Oba tightly controlled its export; private African merchants were barred from selling it without royal approval. In return, the Edo people of Benin wanted Portuguese exotic goods that they amassed from their global trade — manillas made in European foundries (a slave trade currency), Maldivian cowrie shells (West Africa’s international currency of West Africa), Indian silk from Calicut (present-day Kozhikode), and glass beads. Sometimes the Portuguese brought horses as gifts too, but since Benin was in the tse-tse belt, the blood sucking flies killed the horses quickly.

Hoping to make Benin another Elmina, the Portuguese pushed for a permanent trading post—and Ughoton, Benin’s port town, filled that role. But the tropics soon reminded them they were out of their depth: d’Aveiro died there in 1504, becoming one of the first European casualties of African diseases.

In the 1500s, West Africa earned its grim nickname: “The White Man’s Grave.” Portuguese explorers and traders, unprotected against malaria and other tropical diseases, died in droves. Most never ventured beyond Ughoton, Benin’s port town—any deeper inland, like the four-day trek to Benin City, could be fatal.

Ambassadors routinely died on the journey. In 1504, explorer Duarte Lopes succumbed to disease, followed by Bastião Fernandes, a trade agent (factor) who died in 1506 after just 20 months on duty. Others stationed at Ughoton didn’t last long either. The constant death of Europeans in the African interior made the King of Portugal close the post in 1507.

Even after the Portuguese trading post at Ughoton declined, the trade didn’t stop—it simply shifted offshore. By the early 1500s, the islands of São Tomé and Príncipe had become the new hub for Portuguese activity in the Gulf of Guinea.

A Portuguese-speaking, Mulatto Creole population had emerged there in 1494, made up of deported Jewish children, African slaves, and Portuguese settlers. These acclimatized islanders, immune to tropical disease and skilled in sailing, became the key intermediaries for navigating West Africa’s rivers and coasts and trading slaves.

In 1500, the Portuguese Crown granted Fernao de Mello a captaincy at Elmina, forming a royal-private trading partnership. Mello would bring ships with Mulatto Creoles from Sao Tome, while the Casa da Mina, the Crown’s West African trade office, supplied goods — including 16,000 copper manillas — to purchase slaves and pepper, especially from the Kingdom of Benin. The Benin received guns from Sao Tome and used them to wage wars against rivals, like the Uromi.

By the 1510s problem with slaves amounted. The captain of Elmina Castle complained to Portuguese King Manuel in 1513 that he couldn't send enough gold to Portugal due to a lack of trade goods & slaves to sell Africans.

This was because Oba Esigie of Benin started to not cooperate with selling slaves. This occurred because Portugal restricted selling Benin firearms, since the Benin Kingdom wasn’t serious about becoming Catholic. Portugal only wanted to sell guns to Christian Africans for their protection & evangelization, like they did with Kongo.

Since Benin wasn’t getting firearms, the Oba was annoyed with Portugal and ordered his people to seize a Portuguese cannon.

Then, Oba Esigie started to become really crafty with the Portuguese look at the passage below:

The Oba wielded the slave trade like a weapon against Portugal. Unlike later colonization, this was African agency in action— he rose slave prices without warning, separated male and female slave markets, choked supply when he felt like it. His ultimate power move? He banned the export of male slaves entirely, annoying Portuguese plantations and gold trading operations with a single decree.

After many failed attempts to reopen the slave trade and covert the Edo to Catholicism, by 1553, Portugal ended trade with Benin.

After Benin banned selling slaves, Portugal found willing African partners: Ijebu Yoruba, Itsekiri, Douala (in modern day Cameroon), Allada, Kongolese, and others. They didn’t just sell slaves, some were willing to become Catholic and sell ivory as well.

After Portugal conquered the coasts of Brazil in the 1500s things changed. Natives died by European diseases (smallpox & measles), and Portugal needed labor to work in back-breaking heat to work in sugar plantations. Enter African trading partners… Around the 1530s in when the Transatlantic slave trade truly began the one that is more emphasized in your American history textbooks.

In November 1532, the Portuguese ship Santo Antonio carried 201 slaves from São Tomé to Santo Domingo and San Juan, marking the first recorded Middle Passage voyage. The next year (1533), 490 slaves were sent, and in 1534, the number rose to 651.

While the Portuguese kickstarted their Trans-Atlantic Slave trade, Benin focused on its imperial expansion. Benin was able to impose tribute as far as Lagos Island. In addition, France, Dutch, and English also came in to buy peppers from Benin. But we’ll focus on that next time.

Conclusion

Between 1100 and 1560, the Igbo, Yoruba, and Edo shaped a diverse Southern Nigeria. The Igbo of Nri lived in decentralized, sacred villages. The Yoruba built cavalry kingdoms that rose and fell in waves of war. The Edo forged an imperial monarchy that traded with Europe on its own terms.

Now for my “comfortable and uncomfortable truths” corner:

Comfortable Truth: It’s often said that “Africans didn’t have writing before Europeans.” While that’s broadly true for much of sub-Saharan Africa—and while mass literacy didn’t emerge until the post-independence era—Nigeria, just like Ethiopia, Eritrea, Mali, Mauritania, & Sudan, had literate classes long before colonialism. A minority of Igbos used their secret Nsibidi script. The Muslim Yoruba later adopted Ajami. The Edo learned to write in Portuguese for trade. In Part II & Part III, I mentioned that Northern Nigerians (Kanuri, Hausa, Fulani) had Arabic & Ajami literacy centuries earlier.

Uncomfortable Truth: The European slave trade was negotiated, not simply imposed. The Fante demanded slaves for their gold. Benin stopped selling male slaves when it suited them. Other African polities embraced the trade. Portugal and other Europeans couldn’t raid inland communities — they lacked immunity to tropical diseases and were largely confined to the coasts until the 1800s.

Next time in Part V, we’ll discuss what occurred in Southern Nigeria after 1560. We’ll talk about the Atlantic slave trade expansion, the rebirth of Oyo, the Benin Civil War, and more.

Book Sources

An Igbo Civilization: Nri Kingdom & Hegemony by M.A. Onwuejeogwu,

Benin & The Europeans by A. F. C Ryder

The Yoruba: A New History by Akinwumi Ogundiran

The Fate of Africa by Martin Meredith

A History of Nigeria: Toyin Falola

Let me know you think of the comfortable and uncomfortable truths column in the conclusion!

I got "hung up" on the beadwork. So much beauty and skill! You worked hard on this, Yaw. I'll enjoy reading and rereading it. Don't see anything about the Efik or Obibio, however. I lived in that area near the Cross River.