India’s Comeback Story: Gold, Crisis, & the IMF Deal

No, the IMF Didn’t Steal India’s Gold — Here’s What Really Happened

A friend recently asked me: “I loved your IMF Part II article and I think its very informative, but I think you might be incorrect about the IMF not stealing resources. I heard the IMF stole Indian gold in the early 1990s. Can you look into that?”

I'm not an expert in Indian history, so I did my research: I read “Forks in the Road” My Days at Reserve Bank of India and Beyond by Chakravarthi Rangarajan (the 19th governor of the Reserve bank of India) and consulted Indian friends to cross-check the facts.

I looked into it. And here’s my conclusion, no, the IMF didn’t steal gold.

But the truth behind India’s 1991 gold pledge is more fascinating — and more misunderstood — than you’d think. India didn’t “give” gold to the IMF. Instead, India’s central bank (the Reserve Bank of India or RBI) pledged 67 tones of gold to the Bank of England, Bank of Japan, and Union Bank of Switzerland (UBS) to raise emergency cash, buy time to negotiate with the IMF, and avoid default in July 1991. These were collateralized loans and repurchase agreements, not sales. India repaid the loans later that year.

This is actually a high-stakes tale of a desperate India pawning its gold to stay afloat—then clawing its way back to repay every last lender.

To understand this story, I’ll have to explain balance of payments, repurchase agreements, and collateralized loans. So bear with me. To make sense of it all, we need to understand the kind of country India was before 1991—and how the crisis in the early ’90s unfolded.

What Did India’s Economy Look Like in 1991?

Before the crisis, India’s economy was a tightly controlled, inward-looking system often described as the “License Raj.” Nearly every aspect of economic activity—from opening a factory to importing goods—required government approval.

India was among the world’s poorest countries—the average Indian was poorer than citizens of Nigeria, the Philippines, Ghana, Pakistan, Tanzania, or Kenya. Today, India has surpassed all of them in per capita income—except the Philippines.

The pre-1991 Indian economy was characterized by limited private sector dynamism, restrictive trade and investment policies, slow growth, and loss-making public enterprises propped up by state subsidies.

What Triggered the Indian 1990s Crisis?

India was running a fixed exchange rate from 1975–1992. That meant the RBI (India’s Central Bank) had to intervene and sell foreign currency (like USD, yen, pounds) to artificially maintain the rupee’s value.

Why did India intervene in currency markets?

India intervened to artificially strengthen the rupee, making imports cheaper and boosting living standards—at least on the surface. By holding the rupee above its true market value, India created a gap between the official exchange rate and the black market rate, where the rupee traded at its market worth. But this system was unsustainable. Eventually, India began running out of foreign reserves.

Several factors led to this crisis:

High Deficits and Foreign Borrowing: In the 1980s, India ran large fiscal deficits—often over 5% of GDP—financed by foreign currency borrowing and high-yielding deposits from Non-Resident Indians (NRIs). Though marketed as patriotic remittances, NRI deposits functioned as expensive external debt, requiring attractive returns. This growing reliance on foreign funding for budget deficits laid the groundwork for India’s 1991 balance of payments crisis.

Thanks to this excessive borrowing, in a decade, India’s external (foreign denominated) debt quadrupled from $18B to $72B. Interest as a percent of government revenue exploded from 20% of government revenue to 30% over 10 years.

High Oil Import Prices: Oil prices spiked during the Gulf War, as the war halted Kuwaiti production.

Rising oil import costs widened India’s current account deficit (importing more than exporting). With a fixed exchange rate, dwindling foreign reserves meant losing the ability to defend the rupee’s value.

Loss of remittances. India had to airlift 100K+ Indians in Kuwait during the Gulf war (the largest civilian airlift in human history). That affected monthly inflows of foreign exchange.

Sluggish Exports: India’s largest export market at the time was the United States, which was in a brief recession between 1990 to 1991. Due to the decrease in American buyers for Indian goods, India was making less foreign exchange in exports in 1991.

The Shield From Moscow Died. From the 1960s to the 1980s, India imported oil, arms, and machinery from the Soviet Union through a rupee–ruble clearing system. Payments were made in rupees, not dollars, managed by the Reserve Bank of India and the Bank for Foreign Trade of the USSR. The USSR spent those rupees on Indian goods like tea, textiles, and pharmaceuticals. This barter-like arrangement offered India subsidized prices, long-term credit, and protection from currency shocks. But by 1990, the Soviet Union was unraveling, the Berlin Wall had fallen, and the Soviet-Afghan war ended in disaster. Without Moscow’s subsidized oil shield, India was suddenly exposed to the hard currency costs of global oil — and vulnerable.

Structural economic issues — lack of export competitiveness and sluggish government owned enterprises.

Massive government borrowing, rising oil prices from the Gulf War, a shift toward dollar-based trade as Moscow faltered, sluggish exports, low remittance inflows, and a sluggish private sector—all collided to push India into crisis.

December 1990: Only $1.2B Left in Reserves

By December of 1990, India had less than $1B in reserves, barely enough to cover three weeks of imports for essentials like fuel, food, or medicine. You are considered to be in deep emergency if you have less than three months of reserves. India also had $2B in total foreign debt interest & principal due by July 1991. During this time, the Indian government urgently imposed import controls, licenses, and tariffs to prevent imports, maintain its foreign reserves, and prevent economic collapse.

In January 1991, India received a 1.8B IMF Loan ($800M first credit tranche and $1B in compensatory and contingency financing facility), which gave India the foreign debt it needed to pay foreign bond holders.

While India was getting funds from the IMF, India’s credit rating was downgraded to Baa3 or "junk" by Moody's. India couldn’t borrow from commercial lenders and World Bank and ADB don’t lend into active crises. India had very few options.

Q1: Why didn’t India default?

India was a country obsessed with sovereignty in multiple dimensions - geopolitical and economic. The idea of being at the mercy of foreign creditors after a default was unacceptable to the Indian government.

Q2: Why didn’t India just print money?

India couldn’t simply print its way out of the 1991 crisis. The debt due was in foreign currency, like dollars—but India prints rupees, which can’t be used to repay dollar-denominated loans.

Q3: Why not just convert rupees to dollars and print enough rupees to pay off debt?

The rupee wasn’t a convertible currency back then. If India made the rupee convertible during a crisis, there would’ve been a rush by traders, investors, and corporations to convert rupees into dollars. The RBI’s foreign exchange reserves would’ve been wiped out, crashing the rupee and triggering a default.

Even if India tried printing rupees and buying dollars on the open market, it would’ve had to offer more and more rupees to attract dollar sellers — the rupee would depreciate at auctions. That would have led to a currency collapse, soaring inflation, and capital flight—especially by NRIs whose deposits were tied to the rupee. In short, printing money would’ve deepened the crisis, not solved it. India wisely avoided what we might now call the "Zimbabwe option."

Q4: Why didn’t India just borrow new dollar-denominated debt?

By 1991, India’s credit rating had been downgraded to junk. That meant no investor would lend to India unless interest rates were extraordinarily high—if at all.

Even syndicated commercial loans were off the table, as banks saw India as too risky. And multilateral lenders like the World Bank or Asian Development Bank are cautious about lending to countries in freefall, since it could threaten their own AAA ratings.

In short, India was un-investable. That’s why it had no choice but to turn to the IMF—and accept tough reforms in exchange for emergency funding.

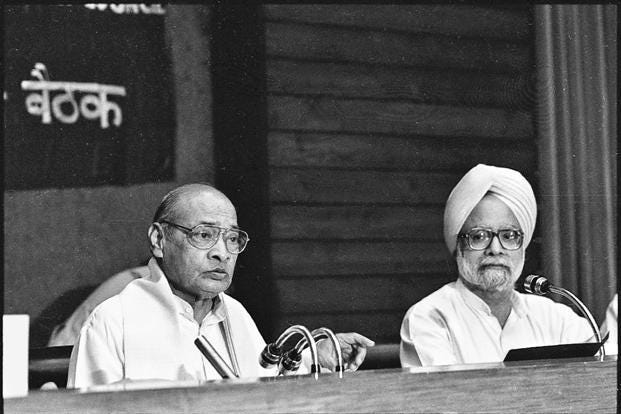

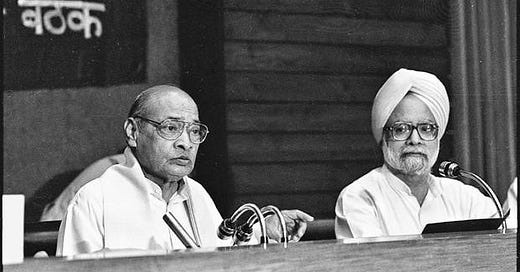

In June 1991, Narasimha Rao became Prime Minister and Dr. Manmohan Singh was appointed as finance minister.

Rao inherited a crisis where emergency import controls were already in place. In response, he announced a partial liberalization program, began dismantling the License Raj, and finalized IMF negotiations.

Turning to the IMF & Gold

This wasn’t India’s first IMF loan — India had previously approached the IMF in 1957, 1962, 1963, 1965, and 1981. But its track record was mixed: reforms were often half-hearted or abandoned midstream.

This time, India entered intense negotiations with the IMF, World Bank, and Asian Development Bank. But while negotiating, India needed immediate foreign exchange — fast enough to avoid default.

To buy time, India pledged 67 tones of gold as collateral for $639 million in quick-disbursing short-term loans. These were not arranged by the IMF but by commercial and central banks that could release funds quickly against physical gold.

First tranche: In May 1991 (before Dr. Singh was finance minister in June), the State Bank of India sold 20 tones of gold to UBS under a repurchase (repo) agreement, raising $234 million. A short-term loan where you "sell" an asset (like gold) but agree to buy it back later at a premium — in this case, with 6% interest. The gold was flown to Switzerland as collateral, but India retained the right to reclaim it upon repayment. In short, a repo is borrowing money by handing over something valuable (like gold) as a promise for a short time — India gets the gold back when it repays the loan with a little extra.

Second tranche: In July, the Reserve Bank of India pledged 47 tones of gold to the Bank of England and Bank of Japan, securing a $405 million loan. This was a collateralized loan, not a sale — India kept ownership of the gold, but the bars were held abroad. If India defaulted, the banks could sell India’s gold; if not, it would be returned to India.

Pledging gold was a high-stakes move that signaled credibility. It showed international investors, credit agencies, and lenders that India was serious about meeting its obligations — even willing to put up hard assets. Most countries don’t pledge their gold because gold assets are seen as natural security. India was determined.

Asking Friends for Help

India had good relations with both Germany and Japan. Together, Germany and Japan sent a total of $400M in bilateral aid to India during the crisis.

IMF Bailout: July 1991

By July 1991, India received another $220M IMF loan. Afterwards, India devalued its currency twice in July by 20% to make exports more competitive & maintain foreign exchange.

With these gold-backed loans ($639M), IMF disbursement (~$2B), German & Japanese aid ($400M total), curbing imports to maintain remaining reserves and remittance inflows (~$200–400M), India scraped together roughly $3.2 to $3.4 billion — enough to cover the $2.2B in external payments due by July.

By August, after paying bondholders, India had about $1B left in reserves. Continued tight import controls, rising remittances, and exports allowed India to repurchase its pledged gold by the end of the year:

47 tones from the Bank of England and Japan by September–November (~$400M + additional interest)

20 tones from UBS by November–December (an additional ~$234M + interest)

Although the gold stayed in foreign vaults, legal ownership returned to India. The Bank of England remains a custodian for over 70 countries’ gold (including Germany, Switzerland, and Belgium), but in recent years, India has repatriated much of its bullion—preferring it stored at home.

Turning Crisis into Reform

Singh’s timing was crucial—most countries wouldn’t have succeeded in repaying high-interest loans by mortgaging gold, but India did. But now, Dr. Singh used the crisis as a pivot.

In return for support from the IMF and World Bank (including a $500M World Bank loan), India launched partial liberalization reforms:

Shift from a fixed to a managed float exchange rate

Allowing foreign direct investment up to 51% ownership in key sectors

Abolishing import licenses for most capital and intermediate goods

The reasons for Indian growth and African stagnation is multicausal—like the end of the 2000s China-driven commodity boom in 2014 and recent debt crises in Ghana, Ethiopia, and others. While too complex to fully unpack here, one key factor was India’s partial economic liberalization, which helped it grow from half as poor as the average Black African to about 50% richer.

India likely won’t need to pledge its gold again—today, it holds nearly 900 tones in reserves.

In dollar terms, India has nearly $700B in foreign exchange reserves now.

India’s Growth: Not a Free Market Fairy Tale

Let’s be clear—this isn’t a story of pure free-market triumph. India is not a free-market economy, and the 1991 reforms were only a partial liberalization, not a full embrace of neoliberalism. Many aspects of India’s economy today would make a U.S. center-right economist wince:

State-Owned Giants: The government still owns major enterprises like Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC), Coal India Limited (CIL), State Bank of India (SBI), Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC), Indian Railways, Steel Authority of India Limited (SAIL), and more

Price Controls and Subsidies: India distorts prices on fertilizer, fuel, food, and electricity. While the U.S. subsidizes producers (e.g., farmers), India subsidizes production & consumption to make goods affordable.

Foreign Investment Caps: Sensitive sectors like defense still limit foreign ownership.

High Tariffs: Especially on agriculture, electronics, and auto parts—India remains deeply protectionist.

Licensing and Import Restrictions: Legacy controls still protect local producers from competition.

India is still in its developmentalist phase—trying to protect its industries while selectively opening up. It’s not a story of India “embraced free markets and got rich.” India liberalized where it made sense—or where interest group resistance was weakest—while keeping firm control in “strategic” sectors.

One of the best descriptions I’ve heard of India’s economy is:

A mostly capitalist engine, with socialist shock absorbers, steered by a bureaucratic wheel.

Concluding Thoughts

India is arguably the IMF’s favorite case study. (I’ve heard former IMF staff cite it as a defense of the institution’s relevance.) The narrative is clean:

A socialist economy hits crisis—due to mismanagement, the collapse of Soviet oil support, the Gulf War, and a draining of foreign reserves.

The government turns to the IMF for help.

India liberalizes

The result: India grows steadily, opens to the world, and becomes an emerging giant.

That’s the version the IMF tells. And it’s not entirely wrong. But, Prime Minister Rao deserves credit for steering reforms selectively, preserving state control where necessary while opening up in key areas. You can say Rao was the Indian Deng Xiaoping.

We shouldn’t forget: Russia and many African countries also tried IMF-backed reforms in the 1980s and 1990s—with far worse outcomes. It’s tempting to say “just add markets,” but success depends on how reforms are implemented—shaped by vision, timing, luck, foreign relations, state capacity, and leadership. For another example of a country that took IMF loans to do reforms that worked, see my piece: “How Deng Xiaopeng Outsmarted the IMF.” (I should clarify that although China took IMF loans, but reforms weren’t IMF-led). If you want to read a failure example, check out “From Communism to Oligarchy: How Russia’s Privatization Failed”

Final Thought: No, the IMF Didn’t Steal India’s Gold

Let’s also put to rest a common myth: the IMF did not steal India’s gold. I think this myth comes from two places.

Firstly, while the IMF didn't receive the gold, its role in coordinating market reforms during this crisis gave the perception of external pressure. Secondly, India pledged its gold in repo-style & secured loan agreements—essentially secured short-term loans— with European & Japanese banks and bought it all back within months. The confusion comes from how finance is often explained. Words like balance of payments crisis or secured repo can sound intimidating, so some turn complexity into conspiracy by saying “the IMF stole India’s gold”. I am sure for many people its a shorthand expression, but the problem is when shorthand becomes accepted as fact.

But the reality is simple: India, facing a crisis, used its gold as collateral, raised cash, avoided default, reformed strategically—and got its gold back.

That's not theft. That's a comeback story.

# India's Backwards Liberalization: Why Elite Priorities Got It Wrong

I was not aware that there were conspiracy theories about Indians losing their gold in the 90s. Honestly, I'm not that surprised. Indians are very sentimental when it comes to gold. When I was growing up in the 2000s, there were a bunch of melodramatic Bollywood movies where basically the worst thing you could do to your family was to use your mom's jewelry as collateral. I always found it strange. Like the main character didn't even lose it—he just collateralized it. What the hell, mate.

The transition to freer markets in India is a lot more complicated than just the push by the IMF. Manmohan Singh had been writing about the failures of the old license Raj system since the late 60s. I think you can find a lot of his old papers online. In the 80s there was Rajiv Gandhi who did some very modest pro-business reforms, allowing imports of computers and such. But obviously everyone around him was still socialist, so they were still creating more state-owned enterprises back then.

What was particularly impressive around the 90s and 2000s was that Rao and Singh did such dramatic reforms in a coalition government. He even tried to increase federalism in India. They and their successor governments, which were also coalitions, did much more to accelerate liberalization than the IMF demanded. The Indian prime minister was clearly in the driver's seat and not just taking orders from the IMF.

I would recommend you look up Singh's 1991 budget speech. This doesn't have the victimhood nor the cowardice that you see in modern-day "Global South" leaders. The Modi decade in relation has been relatively less dramatic in comparison. Although he talked big game about privatization, other than the airline privatization, he mostly chickened out for the rest.

An often underexplored fact was how strange India's liberalization agenda was. In most post-communist countries, liberalization was concentrated in agriculture, low-skill manufacturing, and construction while more white-collar professions were insulated from free markets—like China and Bangladesh. Instead, in India you see liberalization concentrated in more white-collar and asset-heavy investments like telecoms, airports, private equity, etc. Agriculture in India is still mostly a shit show.

In fact, private equity was so regulated in Bangladesh that the government gave up and created their own state private venture capital fund to get the software startup ecosystem going. This kind of shows Indian elites have a big problem with pursuing Western fads instead of focusing on their own problems. They spend too much time on renewable energy or plastic straws or LLM stuff instead of hiring more judges and stopping teacher absenteeism.

The hard reforms were executed primarily by Prime Minister PV Narsimha Rao. Since he became persona non grata for the family that rules his political party, Rao became a political orphan after his term ended, and consequently Dr Manmohan Singh's role in pushing those reforms through was exaggerated at his expense.

Dr Singh was a bureaucrat. He had zero political heft or wiles to get any of the reforms through parliament.

Narsimha Rao, not Singh, was India's Deng Xiaopeng.