Book Review & Insights #5: The Problem of Democracy: America, the Middle East and the Rise & Fall of An Idea by Shadi Hamid

The Tension between Liberalism and Democracy

This is my fifth book review. Here’s how I’ve scored others:

Now, shifting from economics to geopolitics and religion, I review The Problem of Democracy: America, the Middle East, and the Rise and Fall of an Idea by Shadi Hamid.

My rating: 90%.

About the Author: Shadi Hamid

Shadi Hamid is one of the most thought-provoking voices in political science and religion today. An Egyptian-American Muslim, he grew up in Pennsylvania but spent summers in Egypt, where he witnessed the despair of life under Mubarak’s authoritarian regime. Those formative years shaped his deep commitment to democracy and resistance to dictatorship. Hamid holds degrees from Georgetown and a Ph.D. in politics from Oxford.

The Central Dilemma: Democracy vs. Liberalism

Hamid’s core question: What should democratic countries do when elections produce illiberal outcomes?

In the West, voters are allowed to make the “wrong” choice—think Trump or Brexit. But when Arabs make theirs—often by electing Islamist parties—Washington hits the brakes.

Former Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger once said:

Just replace "communist" with "Islamist" and “Chilean” with “Arab” and you have the logic of U.S. policy towards Middle Eastern democracy.

When Elections Go ‘Wrong’: The Freedom Agenda and the Islamist Backlash

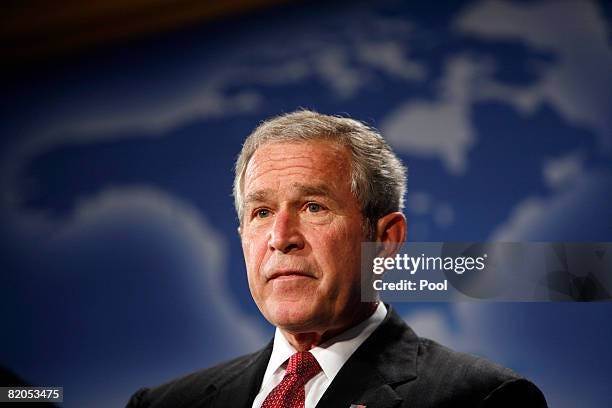

The contradiction in U.S. foreign policy became clearest during George W. Bush’s “Freedom Agenda.” In the wake of 9/11, the Bush administration promoted democracy as a cure for extremism. His logic was: dictators breed despair, despair breeds radicalism. So— use American carrots & sticks (aid, technical assistance, trade deals, cheap loans, military weapons) to promote elections.

What followed was a wave of democratic openings across the Arab world. And what followed that? Islamist victories.

Egypt (2005): The Muslim Brotherhood made gains under Mubarak’s managed pluralism in the legislative elections.

Bahrain and Lebanon (2006): Islamist-aligned parties surged… Especially Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Palestine (2006): Hamas won a surprise victory in legislative elections.

The result? The Bush administration quickly abandoned its democracy push. Instead of adjusting to the new political landscape, it doubled down on its traditional allies—secular autocrats and compliant monarchies.

The message was clear: democracy is fine, unless the wrong people win.

Shadi Hamid’s Central Argument: Democratic Minimalism

This is where Hamid steps in with his sharpest contribution: democratic minimalism.

He argues that the U.S. should stop trying to export liberal democracy—a model that combines elections with a specific set of values like gender equality, minority rights, and secularism. Instead, it should focus on procedural democracy: free and fair elections, peaceful transfer of power, and rule-based governance.

Yes, this might produce risks for U.S. interests (protecting Israel, ensuring Middle Eastern states share Intel with the CIA, keeping Middle Eastern bases, ensuring American freedom of navigation in the region, and etc.). But they also represent the will of their people. And if America claims to support democracy, then Shadi thinks America needs to accept democracy’s messiness.

In Hamid’s view, real consistency—not selective idealism—would strengthen America’s moral standing. Hamid strongly opposes American support for Arab autocracies, whether "soft" (Jordan, Morocco) or "hard" (Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt, Kuwait). He argues that America's support for these regimes undermines its proclaimed values, making slogans like Biden’s "democracy vs. autocracy" seem like empty nonsense.

When it comes to Israel, Shadi believes that America should encourage Arab states to become democratic, while guaranteeing Israeli security (which it already does) to deter Islamists for seeking to destroy the state.

What is Islamism?

As Shadi Hamid explains, Islamism is the belief that Islam should shape public life, law, and politics—not to be confused with violent jihadism like ISIS or Al-Qaeda. While Western audiences often compare Islamists to religious conservatives, Islamist parties from the Muslim Brotherhood movement in the Middle East command far broader support. Polls consistently show that Arabs want Islam to play a role in governance—not just private morality.

Islam vs. Christianity

Yet many Western Secular liberals assume the Middle East just needs to "modernize"—that is, secularize—like Europe once did: Catholic hegemony → Protestant Reformation → Wars of Religion → Enlightenment → Liberal democracy. But Hamid argues that this model doesn’t apply. Islam’s historical arc is fundamentally different.

Unlike Christianity, Islam was political from the beginning. The Prophet Muhammad was not just a spiritual leader—he was a head of state in Medina and a military commander. The Qur’an, Hadith, and Sunnah deal with justice, law, warfare, treaties, statecraft, and governance. Early Islamic teachings naturally address political issues because early Muslims immediately had to grapple with running a state.

By contrast, the early Christians of the 1st and 2nd centuries AD were a persecuted minority in the Roman Empire. The New Testament—comprised of the Gospels, the letters of Paul and others, Acts, and Revelation has almost nothing to say about statecraft. What little it offers, like Romans 13, advises believers to submit to authority—not how to rule. Most political content lies in the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh), which Christians see as “fulfilled by Christ” (Hence why Christians refer to the Tanakh as the Old Testament). This theological shift left the New Testament with little to say about statecraft—unlike Islam, where governance has remained central to the religious tradition.

Islam already had a Reformation

Islam has already experienced profound internal transformations—multiple times. When Islam spread beyond the Arabian Peninsula to the Levant, Persia, and beyond, it encountered and absorbed complex philosophical and cultural traditions. The Golden Age of Islam, centered in Baghdad under the Abbasids, saw the rise of Islamic rationalism—Mu‘tazilism, translation movements, and sophisticated theology, law, and science. This was a kind of Enlightenment moment—built not on secularism but on rationalist theology within the religious framework.

Meanwhile, Sufism—the “folk Islam” of the masses—flourished as a mystical counterbalance. And later, in the Ottoman Empire, the Hanafi school—especially in its Turkish form—offered flexibility and pragmatism in Islamic jurisprudence, even accommodating secular rule under the sultans. These were evolutions of the Islamic tradition, adapted to new political and social realities.

The Attempted Secularization of Islam

In the 20th century, there were serious attempts of privatizing Islam. After the collapse of the Ottoman Turkish Caliphate in 1924, the British and French redrew the Middle East into modern, secular, Westphalia nation-states.

Many post-independent, anti-Western Arab Elites overthrew their British/French installed Monarchies and embraced Arab socialism and secular nationalism—from Nasser in Egypt, Baathists in Iraq & Syria, Bourguiba in Tunis, Boumédiène in Algeria, and more. Their modernization projects sidelined Islam from public life, and it failed due to continuous geopolitical losses and economic failures.

Out of that vacuum, Islamists emerged—not as medieval throwbacks, but as products of modern history. From the 19th-century thinkers like Jamal al-Din al-Afghani and Muhammad Abduh, to 20th-century movements like the Muslim Brotherhood, Islamism sought to reassert the public role of Islam within the Westphalian nation-state. Unlike jihadists, Islamists don’t seek to destroy the state—they want to reform it in line with Islamic principles of justice, morality, and law. They accept elections. They run political parties. They organize protests, not caliphates.

So when secular liberals say Islam needs to “modernize,” what they’re really doing is projecting Europe’s historical trauma—Reformation, wars of religion, and Enlightenment—onto a civilization with a different starting point.

Case Study #1: Palestine – The Democracy America Regretted

In January 2006, after Israel left the Gaza Strip in 2005, Hamas shocked the West by winning a plurality in the Palestinian legislative elections. The vote was free, fair, and internationally monitored. But it wasn’t the outcome Washington hoped for.

U.S. officials, naively expecting a win for the “moderate” Fatah party, were shocked. Many Palestinians, however, were fed up with Fatah’s corruption and drawn to Hamas’s reputation for social welfare work—building schools, clinics, and food distribution networks.

What followed was a slow-motion unraveling:

June 2006: Israel assassinated Hamas appointee Jamal Abu Samhadana. Days later, Israeli shelling killed Palestinian civilians on a Gaza beach.

Retaliation: Hamas militants tunneled into Israel, killing two soldiers and capturing one (Gilad Shalit). Israel launched Operation Summer Rains.

2007: After months of tension and failed unity talks, Hamas seized control of Gaza, killing Fatah officials in Gaza. Israel and Egypt imposed a blockade. The U.S. quietly supported it.

Bush’s subsequent efforts to bolster Fatah against Hamas failed, highlighting a critical flaw in U.S. foreign policy: America loves to say they promote democracy in theory, but when it comes to the Middle East, America is not comfortable with democracy’s outcomes in practice.

This partly lead to the issue we see today. Some people think Bush was an idiot for allowing Palestinian elections.

Case Study #2: Egypt — The Repression of Islamic Democracy

Egypt’s experiment with republicanism began in 1952, when Gamal Abdel Nasser and the Free Officers overthrew the monarchy. He championed Arab nationalism and land reform, but his regime became increasingly autocratic—especially after Egypt’s defeats in Yemen and the 1967 war with Israel.

Nasser died in 1970. His successor, Anwar Sadat, shifted course after the 1973 war: he embraced the U.S., expelled Soviet advisors, and in 1977 became the first Arab leader to visit Israel. His 1978 Camp David Accords made Egypt the first Arab state to recognize Israel—earning Sadat Western acclaim and permanent U.S. military aid. This move made him a hero in the West, but a traitor at home. In 1981, Sadat was assassinated by Islamist army officers during a military parade.

Then came Hosni Mubarak, who ruled for 30 years. In the 1980s, he allowed limited political space for the Muslim Brotherhood. During this time, Egypt received Major Non-NATO Ally status. In 1987, the Brotherhood-aligned Islamic Alliance made electoral gains. By the 2000s, they had growing influence in professional unions and elections—alarming the government. Mubarak responded with repression and rigged elections, backed by $1.3 billion a year in U.S. aid, justified by Egypt’s peace with Israel.

The Arab Spring changed everything. In 2011, massive protests ousted Mubarak.

Free elections followed—and the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi became Egypt’s first civilian president.

His rule was short and divisive. Morsi passed an Islamist constitution, alienated liberals and minorities, and assumed sweeping emergency powers. Despite brokering a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas in 2012, Morsi was seen by many as governing for the Brotherhood, not the nation. In 2013, the military removed him. Weeks later, over 1,000 of his supporters were massacred in Rabaa Square. Now Al-Sisi, another military leader, rules Egypt.

Takeaway: Egypt tried democracy. The U.S. tolerated a coup, a massacre, and a return to military rule—so long as the peace with Israel held. Stability won; democracy lost.

Case Study #3: Algeria - The Election that Triggered a Civil War

Algeria won independence from France in a brutal anti-colonial war in 1962 and was ruled by the FLN—an autocratic, socialist party backed by the military. By the late 1980s, falling oil prices sparked economic crisis and riots. The regime turned to the IMF, slashed subsidies, and President Chadli Bendjedid introduced multiparty elections.

Enter the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS)—a grassroots Islamist party riding a wave of urban discontent. It won local elections in 1990 and dominated the first round of parliamentary elections in 1991. FIS was poised to win an absolute majority in the second round.

The military panicked. In January 1992, the army canceled the elections, dissolved parliament, banned the FIS, and declared a state of emergency. The West barely protested. U.S. Secretary of State James Baker said it plainly:

"We believe that democracy is more than one man, one vote, one time."

In other words, a democratic result that empowered Islamists was not acceptable. America tacitly supported a secular Military dictatorship over possibly having an Islamic one.

What followed was one of the bloodiest civil wars in modern Middle Eastern history. Over 100,000 people died. Islamist militants massacred civilians. The military crushed opposition. The war ended in the early 2000s, but democracy never returned. FIS remains banned. The military still calls the shots.

Takeaway: Algeria’s experience sent a chilling message across the region: if Islamists win, the West is ok with secular dictatorship and civil war over Muslim democracy in the Middle East.

Case Study #4: How The King Weakened Jordanian Democracy to Get a Deal with Israel

Jordan’s Hashemite monarchy wasn’t born out of local independence—it was a product of British imperial design. After World War I, Britain carved out the territory for the Hashemites, a family originally from Mecca, who had been promised rule over all of Arabia in the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence(1915-1916) for rebelling against the Ottoman Empire.

That promise was never kept—Saudi forces drove them out of Mecca, and Britain compensated them with control of Transjordan, Iraq, and Syria. Today, only Jordan remains.

In 1957, when Arab-Socialist, Prime Minister Suleiman al-Nabulsi clashed with King Hussein, the monarchy suspended parliament and imposed martial law. Washington stepped in with a $10 million emergency grant. U.S. aid would exceed Jordan’s own domestic government revenue for much of the Cold War.

During the Cold War, Jordan’s main political divide was Arab socialism vs. Islamism. The Muslim Brotherhood, unlike in Egypt or Syria, was co-opted into the system. The monarchy viewed them as a counterweight to Nasserists and later Palestinian militancy, especially after the 1970 Black September conflict, when King Hussein expelled the PLO after a civil war nearly toppled his rule.

In 1989, an economic crisis made Jordan go to the IMF. The IMF told Jordan to do austerity measures to restore investor confidence. However, the austerity sparked mass protests. The monarchy responded by restoring elections. The Muslim Brotherhood surged, particularly among urban professionals. But when King Hussein moved toward peace with Israel, Islamists became a liability.

Post-Gulf War, after Hussein backed Saddam (due to Jordanians liking Saddam’s anti-Western & anti-Zionist stance at the time) and alienated Gulf donors, Jordan sprinted to Washington. The U.S. rewarded him with debt relief and military support, but H.W. Bush told the King that he had to accept Israel’s right to exist.

In 1993, King Hussein rewrote the electoral law to favor tribal districts loyal to the crown. A new, pliant parliament was in place just in time to ratify the 1994 peace treaty with Israel—deeply unpopular with Jordan’s Palestinian-majority population.

After that, Jordan received Major Non-NATO Ally status.

Elections still happen—but real power lies with the king and his court. Islamist parties still exist but are marginalized through gerrymandering, media control, and legal restrictions.

Takeaway: Jordan’s democracy exists only to the extent it doesn’t threaten the monarchy—or the peace with Israel. The U.S. prefers it that way.

The U.S. tolerates the monarchy’s soft autocracy because it maintains peace with Israel, hosts U.S. military bases, and serves as a regional mediator. But full democracy? That would risk empowering a Palestinian-majority parliament hostile to Israel—and that’s a risk neither Amman nor Washington is willing to take. Without U.S. support, Jordan’s monarchy would’ve likely joined Egypt (Farouq), Syria (Faisal I), Iraq (Faisal II), Libya (Idris), and Tunisia (Muhammad VIII al-Amin) in the graveyard of fallen Arab monarchies.

The Point of the Case Studies

These four cases show some patterns (and I could have used more):

When Islamists win, the West walks away—or worse, enables their removal.

When secular autocrats repress, they get aid if they follow American interests (U.S. military bases for power projection or Israeli support).

The lesson for Arab voters? Democracy is tolerated, but only within tight limits.

This doesn’t just undermine U.S. credibility. It helps entrench the very authoritarianism the West claims to oppose.

What about Israel?

Most Arab populations—whether liberal, nationalist, or Islamist—remain deeply opposed to normalization with Israel. They don’t view Israel as a safe haven for persecuted Jews fleeing pogroms in 19th-century Imperial Russia or genocide in Nazi Europe. Instead, most Arabs see Israel as a Western-backed colonial implant, established through the displacement of Palestinians and sustained through force.

Even when reminded that roughly half of Israel’s Jewish population descends from Middle Eastern and North African Jews—many of whom fled violence, state-sponsored discrimination, or had their homes, synagogues, and businesses destroyed after Israel’s creation—this rarely shifts Arab public opinion. Why? Because those departures are often interpreted not as organic refugee flows, but as part of a broader Zionist project encouraged by Israel itself.

Shadi Hamid doesn’t deny Middle Eastern hatred of Israel. He confronts it.

He argues that America and Israel are making a strategic mistake by aligning closely with Arab monarchies—UAE, Bahrain, & Saudi Arabia—whose leaders can normalize ties with Israel without popular support. In Shadi’s view, these nations don’t need to listen to their citizens. But that makes them fragile to him.

When the Arab Spring shook the region, Bahrain’s monarchy nearly collapsed. In Sudan, the transitional government that signed the Abraham Accords is now gone, replaced by war and chaos. If an Islamist party returns to power in Sudan—as happened under the later era of Nimeiri or Bashir—the Israel deal will vanish with it.

Hamid’s point: Israel must reckon with Arab democracy. It cannot bet its future on autocratic rulers. Instead, it should engage with elected governments—even if they are Islamist.

He cites Mohamed Morsi in Egypt as a test case. Morsi, despite his Brotherhood background, upheld Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel. He needed American aid, international recognition, and economic stability. That’s the logic of democratic constraint.

In other words, Islamist parties may oppose Israel rhetorically, but in power, they often act pragmatically. A democratic Middle East might not love Israel—but it might coexist with it better than a brittle, authoritarian one.

Conclusion

Shadi Hamid’s The Problem of Democracy is a sharp, necessary intervention into a shallow conversation.

He pushes Americans to ask hard questions:

Do Americans believe in democracy—or just in outcomes they like?

Can Islam and democracy coexist—not just theologically, but politically?

And if they can, are Americans prepared to let Middle Eastern societies find their own path?

In my opinion. the answers are:

Only the outcomes America likes

Yes, we see it in Senegal, Malaysia, and Indonesia

Probably not

Hamid isn’t saying democracy in the Middle East will be easy. He’s saying it will be messy, illiberal, and necessary.

There are so many things I didn’t mention and so many concepts that Shadi introduced me that I haven’t heard before. The book is a 90%. Get yourself a copy or an audiobook.

Although I find Shadi Hamid a very thoughtful writer (more importantly, I find his stance against what happened in 2013 courageous when few from the intellectual class in my country (who later became my professors) took it, but I want to point two things a) you said "where he witnessed the despair of life under Mubarak’s authoritarian regime", I think if you told any Egyptian the following (in hindsight), they would laugh. The World Bank even wrote in 2015 "Judging by economic data alone, the Arab Spring should have never happened", Egypt's most prosperous years came from 2002 to 2010, the regime's expansion of bureaucrats, middle class and margin of freedom was its undoing, yes poverty was high and public services were failing but I think the revolution happened due to relative deprivation not absolute one b) Shadi Hamid was viewed by some intellectual in Egypt as someone out of touch with MB's project and what is happening on the ground, he was too focused on theory and grand narratives, and I agree that Shadi in 2012 was not witnessing what others in Egypt saw by the virtue of being pundit abroad (only writes and talks for living) and did not return neither before or after. I remember one of my professors who was christian (currently one of renowned professors on democratization and editor of democratization journal) replied to him on twitter telling him to try coming and living under religious fanatics. Shadi paints only one side of the story "Liberalism vs Democracy" (a correct one) but neglects the authoritarian part of the story like Trump now. The problem is not with electing illberal populists, the problem comes when these populists dismantles the institutions and processes electing and checking them after coming into power. Yes, with the power of hindsight, the threat of MBs was overblown in Egypt and the alternative was not good, but I can understand people with so much chaos in the streets in 2011 and 2013, and real fundamental concerns over governance might pivot to a return to status quo. I do not expect that a continuation of Mubarak would have evaded many problems the current regime witnessed had the revolution never happened, but the effect in my opinion would be smaller. I think the suspicion and criticism received during this period was partly justified. Additionally, despite his credentials, Shadi remains pundit rather a scholar like Tarek Masoud who happens to answer the same question Shadi discussed but empirically. I feel sympathy to Shadi not only because I agree with his priors but I find him attacked by intellectuals in Egypt and by some pro-israel voices in America, yet it is the cost of pursuing the life he chose to.

The book discussing Islamists in the Middle East offers several intriguing insights and challenges common Western perspectives on the subject.

I agree with the critique that Western pundits calling for a Protestant-style reformation within Islam are misguided. This view often stems from a projection of historical paranoia about globalist Catholics onto contemporary globalist Islamists, particularly in the Anglo-Saxon world. In Sunni Islam, individual Muslims have traditionally had the authority to interpret the Qur'an for themselves, negating the need for a Protestant-like reformation.

Support for Islamism does not primarily come from Muslim elites or poor, illiterate villagers. Instead, it is often driven by the newly emerging middle class, similar to the demographic that supported communist movements a century ago.

While the book highlights that Islamists are not necessarily extremist jihadists and are contesting elections, this perspective overlooks crucial details. Islamists often respect elections only as a means to gain power, with the ultimate goal of dismantling the very institutions that allowed their rise. The example of Islamists in Turkey illustrates this point.

Moreover, many Islamist parties operate with a dual structure: a civil, mainstream wing that contests elections, and a more militant wing that intimidates minorities and liberals. The mainstream wing typically disavows any connection to the militant wing but stops short of condemning their violent tactics or supporting legal action against them.

Islamism, much like communism a century ago, is a globalist movement. Even when Islamists run for local elections, they often focus on broader issues like Palestine, adopting neo-colonialist narratives perpetuated by Western leftists. This globalist ideology takes precedence over national interests, leading to potential conflicts with non-Muslim neighboring countries. In Bangladesh, for instance, despite Israel's support for independence, the leadership prioritized aligning with Islamic countries, even sending troops to the 1973 Arab-Israeli war during a domestic famine.