Book Review #3: Where Credit is Due: How Africa's Debt Can Be a Benefit Not a Burden

An Outstanding Guide to Development finance in Africa

For my first book review, Dead Aid, by Dambisa Moyo, I gave it an 86%. For my second, The World for Sale by Jack Farchy & Javier Blas, I rated the book a 95%. For Where Credit is Due: How Africa’s Debt Can be a Benefit Not a Burden by Gregory Smith, I’m giving it a 97%.

Who is Gregory Smith?

Gregory Smith is an economist specializing in emerging and frontier markets. He has worked in global finance at the UN and World Bank and holds a bachelor's and PhD in economics from the University of Nottingham. He has advised Uganda’s Ministry of Finance, the World Bank, the IFC, and has been an emerging market bond investor at M&G Investments and Renaissance Capital. His advising experience, spanning countries like Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Sri Lanka, is valuable for his real-world, practitioner experience focus over pure academia.

Why I Love This Book

This book strikes the perfect balance of breadth and depth in explaining credit markets, both globally and in Africa. Whether you're starting from scratch or looking for a well-sourced guide to the mindset of an emerging/frontier market investor or researcher, this book delivers.

What this Book is About

This book breaks down Africa’s debt landscape at the continental, regional, and national levels, using historical examples to provide depth and context.

He doesn’t skirt talking about colonial history, but the book focuses primarily on Africa’s current sovereign bond market climate.

Africa’s debt situation is a complex mix of domestic borrowing, foreign aid, Eurobonds, multilateral loans, bilateral government loans, and commodity-backed financing. While debt relief movements like Jubilee 2000 and the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative provided temporary relief, many African nations fell back into debt cycles due to structural economic weaknesses. This article explores the sources of debt, the role of different creditors, and the long-term implications of Africa’s borrowing strategies.

I will be going over the key insights that I think are worth sharing.

Insights #1: Why Poor countries Borrow

No country escapes borrowing—whether America, China, Malawi, or Jamaica, debt is essential. It funds infrastructure, healthcare, and education and cushions shocks from disasters, commodity price collapses, and pandemics. But it can also be misused—to buy votes or enable corruption. It’s always about implementation, never about debt itself.

There’s a Maslow’s hierarchy of debt for developing countries. The bottom of the chart is the easiest way for a country to raise funds, and the top is the hardest. Look at the chart I made below:

Developing countries primarily raise funds through taxes, foreign aid, and/or state-owned enterprise earnings, turning to borrowing when these aren't enough. The last resort is the IMF bailout. Here’s the hierarchy of options:

1. Profits from State-Owned Enterprises

Many African countries rely on revenue from state-owned oil, mining, and strategic assets rather than taxes.

Oil government revenue dominates in Libya (97%), Equatorial Guinea(80%), Angola (75%), Congo-Brazzaville (66%), Nigeria (65%), Chad (53%), Algeria (50%), and to a lower extent Gabon (40%) & Cameroon (16%).

Mining revenue buttresses the government budget of Botswana (diamonds), Guinea (bauxite), Mali & Burkina Faso (gold), Mauritania(iron), and Zambia & Congo (copper).

Tolls and port fees fund governments in Egypt (Suez Canal) and Djibouti (port fees, military bases):

The biggest issue with these “rents” supporting government budgets is that the country becomes a slave to the global commodity price. If oil/gold/copper falls so does their government revenue.

Houthi activity in the red sea has plummeted Egypt’s Suez Revenue. If Ethiopia’s deal with Somaliland goes through, then Djibouti loses $1B in port rents. In addition, for all of these countries, these state owned resource enterprises have been black boxes for corruption. It also leads to resource dependence.

The sad part is that many African countries don’t really make that much in oil revenue to support their population sizes. In 2023, Saudi Arabia exported $181B in crude oil, while Nigeria exported $44B. Saudi Arabia’s population is also 37M while Nigeria is guessed estimated to be 220M. This means Saudi Arabians make 25 fold more per person from oil than Nigerians: nearly $5K per capita compared to Nigeria’s $200. If exports per capita reflected resource wealth relative to population, Saudi Arabia is far better endowed..

A regression of oil & gas exports per capita against income per person shows a clear trend: countries with higher exports per capita are richer. This should be patently obvious. More exports mean greater government revenue spread across fewer people, enabling better-funded services and higher incomes.

2. Raising Taxes

Taxation is the next step after “rents”, but in many African nations, it's difficult to collect enough revenue due to:

Widespread poverty: There’s not much income tax to collect if the majority of the population are subsistence farmers, unemployed youth, or informal gig workers.

Corporate tax avoidance: Most African businesses informal or barely profitable. If it is profitable, there’s a good chance that it stashes cash abroad in tax havens like UAE or Mauritius. Or profitable African firms hide income, falsify records, or launder money through offshore shell firms in Seychelles.

Heavy reliance on VAT: VAT is a consumption tax that disproportionately affects the poor and often sparks riots.

All these issues make African countries have low tax to GDP ratios. For context, Nigeria, Uganda, and Kenya have tax-to-GDP ratios of 6.3%, 11.8%, and 17.4%, far below the Latin American & Caribbean average of 23% or the OECD average of 34%.

3. Domestic Borrowing

When tax revenue falls short, governments borrow from local banks and investors. However most African banks and financial institutions lack financial reserves to buy enough government bonds, aka local financial markets can’t finance their governments. The other option is direct debt monetization, a practice that’s illegal in countries like America, EU, and even Japan (Note: Direct Debt monetization is not the same as Quantitative Easing-QE. Direct debt monetization is when the Central Bank prints money to directly buy from the treasury in the primary market, which led to hyperinflation in Weimar Germany, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe. QE is when the Central Bank prints money to buy bonds from banks (not the treasury!) in secondary market. QE does not necessarily lead to inflation as this was used multiple times post-2008 GFC and inflation was low.)

In developing countries, local banks lack the capacity to buy enough government bonds, making QE infeasible. In addition, developing countries want to avoid the Zimbabwe, hyperinflationary direct debt monetization option, so as a result, countries turn to external options.

4. Foreign Aid & Bilateral Loans:

The country may then ask for aid (grants) or bilateral loans (typically zero or low interest credit) from wealthier nations.

Belarus is mainly financed by Russia, and Cambodia, Djibouti, and Zimbabwe are mainly financed by China. Look at their debt profiles below:

5. Multilateral Banks:

If that’s not enough, the country might approach the World Bank or their regional development banks like the Asian Development Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, the Arab Fund for Economic & Social Development, or African Development Bank. But these banks typically lend when a country is in reasonably good economic health, as they aim to maintain their strong credit ratings. They are unlikely to lend to a country teetering on the edge of bankruptcy, often directing the borrower to seek assistance from the IMF.

Countries like Mauritania, Algeria, Guyana, and Liberia depend on these regional banks to raise money.

6. International Borrowing:

When domestic sources fail and the country isn’t getting enough aid or low cost loans to finance their government, then countries usually try international markets, either by securing syndicated loans from banks like Goldman Sachs/Citi/Standard Chartered Bank or issuing Eurobonds to investment firms denominated in US dollars (misnomer I know).

For South Africa, Egypt, China, and Turkey, many international investors can’t or don’t want to buy their local currency bonds, so they go to the eurobond market to raise debt.

However, if a country is deemed too risky—a financial "basket case"—lenders either refuse or demand prohibitively high interest rates, shutting down this option.

7.Commodity-backed loans from traders:

If the country is locked out from other avenues but doesn’t want to go to the IMF, the country can get a commodity backed loan. If a country possesses valuable resources like oil fields, bauxite, or copper mines, it can essentially mortgage those assets to secure financing from companies such as Trafigura or Glencore. This practice has been seen in countries like Jamaica, Congo-Brazzaville, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Chad, and more. These loans are often kept “off the books” and only come to light when the country discloses its full loan portfolio during negotiations with the IMF, often in the context of seeking debt forgiveness.

These shady loans contribute to why Glencore owns 100% of the Mutanda Cobalt Mine in Katanga, Congo

8. IMF Bailout

When all other options are exhausted/avoided, the country turns to the IMF. Since 1976, IMF loans for low-income countries have been offered at concessional, below-market rates through the IMF Trust Fund program. Developing countries resent the IMF because it demands reforms to restore investor confidence, such as currency floatation/devaluation, fuel/food subsidy cuts, and privatization of failing state-owned firms. This is all short term pain, for potential (but not certain!) long term gain or another IMF loan...

In developing countries, low domestic savings—due to low incomes, informal employment, preference for self-investment in a home or business instead of a bank, or capital flight—necessitate greater reliance on external borrowing

Insights #2 Specific Examples on debt markets in African countries

In his book, Greg examines African debt markets, highlighting countries like Kenya, Senegal, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, and more.

I’ll give an example with Senegal.

Like many African nations, Senegal suffered through the African debt crisis of the 1980s–2000s, enduring two lost decades. After qualifying for Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) and Multilateral debt relief, its debt was cut in half from $3.8B to $1.9B by 2006, but that’s a bandage solution. The economy was still largely informal, domestic banks lacked sufficient savings to fund the treasury, and Senegal remained dependent on external borrowing.

Initially, Senegal relied on government and multilateral loans at concessional rates, but in 2009, it turned to the eurobond market for more ambitious projects, raising $200M at 8.75% for five years. In 2011, it issued a $500M, 10-year eurobond at the same yield, using part of the proceeds to pay off its earlier bond and fund projects like the Dakar toll road.

Under President Macky Sall’s "Emerging Senegal" plan, the country repeatedly refinanced debt by issuing larger and longer-maturity eurobonds to pay off old debt in 2014, 2017, and 2018.

The results were mixed. While infrastructure improved—new roads, railways, an airport, and better electricity—Sall’s administration was plagued by corruption and mismanagement. Incomes modestly improved during Sall’s tenure. Annual incomes went from $1327 a year in 2012 to $1706 by 2023, a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 2.31% a year.

While the growth isn’t terrible, it’s not great. If Senegal keeps growing at that rate for the next decade, then by 2033, the average Senegalese will only make $2150 annually, which is still poorer than Ghana or Ivory Coast today.

Insights #3 Africa’s Debt Crises

Debt crises were rampant in the 1980s and 1990s. The Latin American debt crisis (1982–1989) hit Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Venezuela, and more. The Asian financial crisis (1997–1998) affected South Korea, Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Turkey (1994), Russia (1998), and Pakistan (1998–1999) also faced crises.

Africa endured its own debt crisis, but unlike Latin America or East Asia, it suffered two lost decades (1980–2000) of economic stagnation. Nearly every African country, except Botswana—where De Beers hoarded diamonds to maintain high prices—struggled with debt and declined economically. For my in depth analysis, you can read my African Debt Crisis article here.

To see how bad the 1st debt crisis was, look at this Bloomberg graph below from 1980 to 2000:

In fact, Africa, as a whole, has now entered a debt crisis and stagnate living standards again since 2015, hopefully this one doesn’t last until the 2030s, which is the market prediction.

So far we have seen eight African debt defaults since 2016 from Mozambique (2016), Congo-Brazzaville (2016), Zambia (2020), Ghana (2022), Mali (2022), Ethiopia (2023), and Niger (2024).

Investors generally think Burkina Faso and Tunisia are the next countries on the verge of default. Their credit ratings are junk territory.

Insights #4 History of Debt Relief

In the late 90s and early 2000s, advocates, celebrities, activists, and religious groups (including the Pope) rallied a massive movement of debt relief for the developing world. It was called Jubilee 2000.

The activists called on the G7, IMF, African Development Bank, and World Bank to forgive Africa’s global debt, allowing governments to spend more on social programs instead of debt payments.

Debt relief gained momentum with Live 8, while the UK’s Make Poverty History campaign and the Global Call to Action Against Poverty movement further pressured world leaders.

Debt relief for poor countries occurred in two stages. The Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative in the late 1990s and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) in the early 2000s.

Under HIPC, the Paris Club —a group of 22 creditor nations—forgave bilateral debt. This group, which includes the U.S., U.K., France, Germany, Japan, Brazil, Israel, Russia, South Korea, Canada, Australia, and others,

Phase two, was the London Club. Instead of a club of government lenders, this is a group of private banks. Private lenders rarely forgive debt outright; instead, they reschedule it by lowering interest rates, extending loan terms, adding grace periods, and offering minimal write-offs to avoid outright losses. Banks like Goldman Sachs, Citi, JP Morgan, HSBC, Royal Bank of Canada, UBS, Deutsche Bank, and Société Générale were involved in forgiving debt.

Phase three, was the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI). The World Bank, IMF, and African Development Bank took a different approach, paying off multilateral debt for qualifying African nations. Combined with the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative, these efforts eliminated around $100 billion in debt.

Moral Hazard

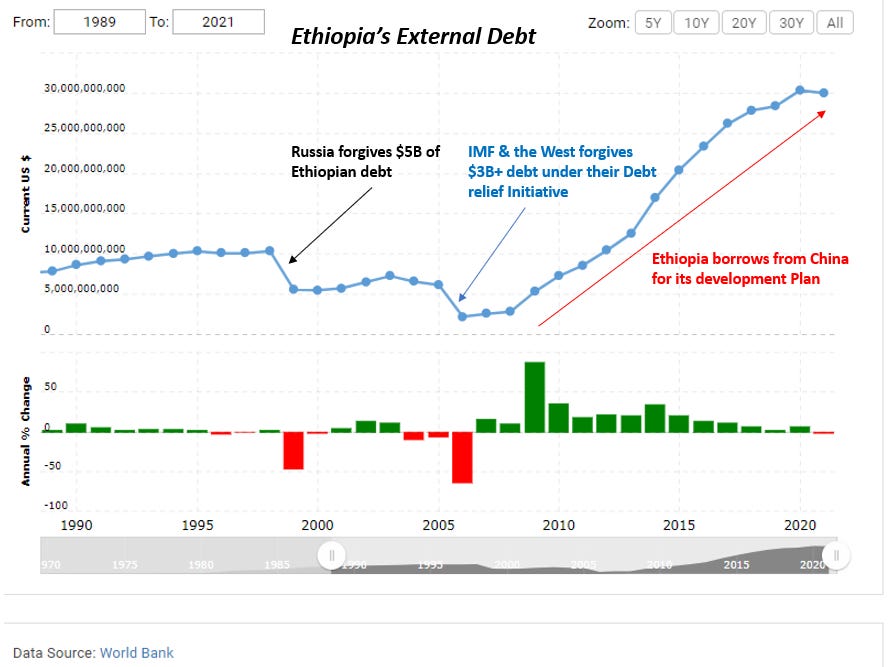

While this certainly made activists feel good, this debt relief is basically putting a bandage over weak financial markets. If you are a poor country where the majority of employment is subsistence farming, fishing, small scale trading, artisanal mining, and/or informal employment, the country cannot raise enough taxes. The local banks and investment firms do not have enough bank deposits from people or businesses to buy government bonds to meet the financing needs over the government. None of them want to be a Zimbabwe, where the central bank directly monetizes the debt, which leads to hyperinflation. This leaves developing nations with one option—borrowing again from foreign creditors. The result? A debt relief —> borrow binge —> default cycle. Ethiopia is a textbook case: it received extensive debt relief from the West & Russia in the late 1990s and 2000s, yet continued borrowing heavily for development. By Christmas 2023, it defaulted.

I can show you a similar debt trajectory of African countries going on borrowing binges after debt relief with Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroon, and other African countries as well.

The African Union is now advocating for another round of debt relief, framing it as reparations for the slave trade. However, support is limited due to moral hazard concerns and political realities—especially since Donald Trump is unlikely to consider it.

Insights #5 Is Chinese “Debt Trap Diplomacy” Real?

I covered this before here. While China is Africa’s largest bilateral lender and has scaled up lending to the continent quickly, the claim that China deliberately issues excessive loans to seize assets is a myth.

Recent African defaults stem from Eurobond debt, not Chinese loans. Countries have struggled to repay private investors (Ghana, Ethiopia, Zambia) or faced sanctions, freezing assets (Mali & Niger). but no African nation has defaulted due to a missed Chinese loan payment yet. The idea that “China lends just to take assets after default” falls apart when no such China loan default has occurred. Even the Sri Lanka example often cited as “debt trap diplomacy” is misleading.

The real issue isn’t “selling sovereignty to China”—it’s African finance ministers pitching investments in London and New York, overhyping the bond investment opportunities of their nations, securing funds, and then failing to deliver returns. Africa’s Eurobond debt exceeds $320B, while debt to China is around $90B, much of the Chinese debt is borrowed at below-market (concessional) rates.

Meanwhile, China’s lending to Africa peaked in 2016 and has declined since, except for a $5B spike in 2023.

The top five borrowers—Kenya, Angola, Egypt, Nigeria, and Ethiopia—account for half of China’s lending to Africa.

Insights #6 Is Who are the top Lenders to African Countries?

Below you can see the chart of the top lenders to the African Continent as of 2023:

The top 10 debt investors to the African continent are international bond investors, the World Bank, Commercial Banks, “Other Multilateral Lenders” (BRICS, UN. non-World Bank), China, the African Development Bank, “Other Bilateral Lenders”, the IMF, France, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait.

The U.S. government is not a major bilateral lender; it primarily provides loans through multilateral institutions like the World Bank, IMF, and regional banks.

Final Thoughts

The book is fairly comprehensive and there’s many things that I did not mention in the book that I found fascinating. Here’s what you could learn about from reading the book:

The Gulf States’ influence in financing African countries

How the global sovereign bond market works, from Eurobonds to Islamic Sukuk bonds

The shadiness of commodity backed loans from commodity trading firms like Glencore, Trafigura, Vitol, Mercuria, and Gunvor

How to look at Sovereign Balance Sheets with predictive power to see if a country will default

More individual case stories of debt management/failure of different African countries

I gave the book a 97% instead of 100% because the "Better Borrowing" section felt a tad incomplete to me. But “solutioneering” is always harder than describing the situation.

Conclusion

If you are looking for a good African finance/macroecon book then “Where Credit is Due” is a fantastic book.

There’s no “permanent debt solution” because every country borrows from the United States to France to Saudi Arabia. But for a developing country to avoid constant defaults and to evolve their junk credit rating to investment grade like the aforementioned countries. then they must reform, foster better business environments to have their own Samsungs or Toyotas, and boost government revenue and foreign reserves to manage debt. Development doesn’t end borrowing; it just shifts from aid, bilateral, and multilateral loans to private markets.

Debt relief doesn’t stop borrowing—it often fuels new cycles of debt until another bailout is needed. There’s no substitution for development.

Amazing work, this is very insightful. 👏

Fantastic Work 👏🏽👏🏽👏🏽