The Start of How Britain Colonized of Nigeria: The Palm oil trade, the Treaties in Calabar and the Conquest of Lagos

Part 7: The start of Nigerian colonization

“The anxiety of Britain to intervene in Lagos was not just the philanthropic desire to destroy the slave trading of the Portuguese and Brazilians there, but also the economic desire to control the trade of Lagos… and from where they hoped to exploit the resources of the vast country stretching to and beyond the Niger” — Ade Ajayi (ah-jah-yee), Nigerian Historian

This is Part VII in our Nigeria series. Part I gave an overview of Nigeria and explored Nigeria’s earliest civilizations.

The series traces how the diverse peoples of what would become Nigeria adapted to four successive waves of globalization—each reshaping their societies before European imperialism in the 19th century:

Globalization 1.0: Trans-Saharan caravans linked Sahelian Africa to North Africa and the Arab world, making Islam take root in polities that would be a part of Northern Nigeria (Part II). By the 19th century, jihad by African Fulani-ethnic clerics transformed the Hausa city-states into the Sokoto Caliphate (Part III).

Globalization 2.0: In the 15th century, Portuguese mariners reached the West African coast. The Coastal Akan-ethnic chiefs demanded captives for their gold mines. The Portuguese supplied them with slaves from the Niger Delta in exchange for gold, which they shipped back to Lisbon (Part IV).

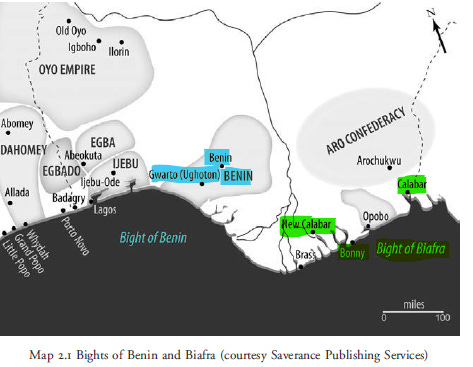

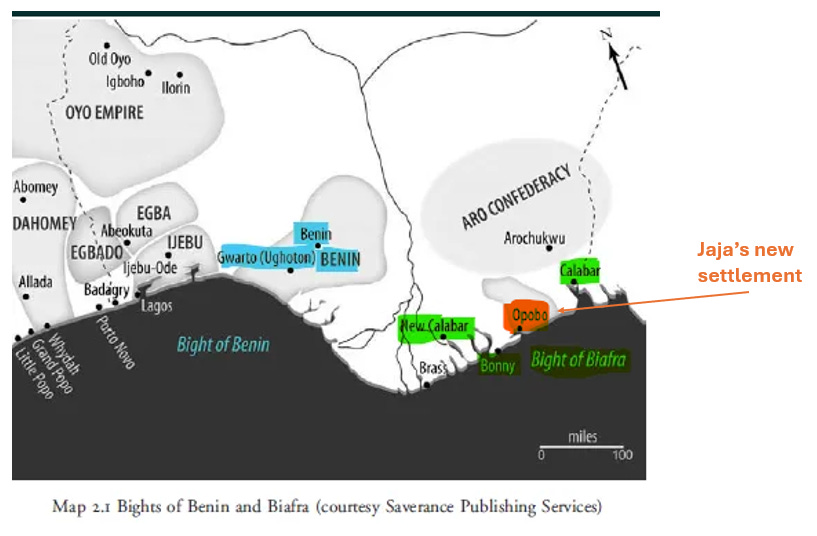

Globalization 3.0: The 16th century saw the rise of the Trans-Atlantic system: Europeans sold cowries, manillas, guns, liquor, and cloth to coastal African middlemen merchants in the Bights of Benin and Biafra. These coastal brokers took slaves from inland African suppliers in exchange for European goods (Parts V & VI).

Globalization 4.0: Now we reach Globalization 4.0 — the start of the creation & colonization of Nigeria. In this article, I’ll cover Britain’s anti-slavery patrols, the palm oil trade, Anglo-French rivalry, the quinine revolution, and finally the conquest of Lagos.

#1 Ending Slave Trade & Rise of “Legitimate Commerce”

Britain's Anti-Slavery Campaign

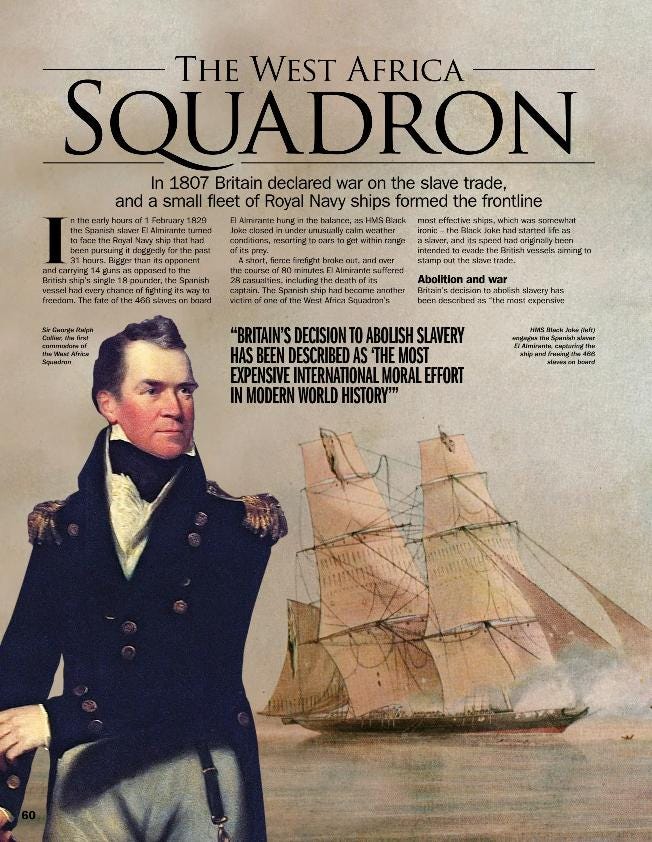

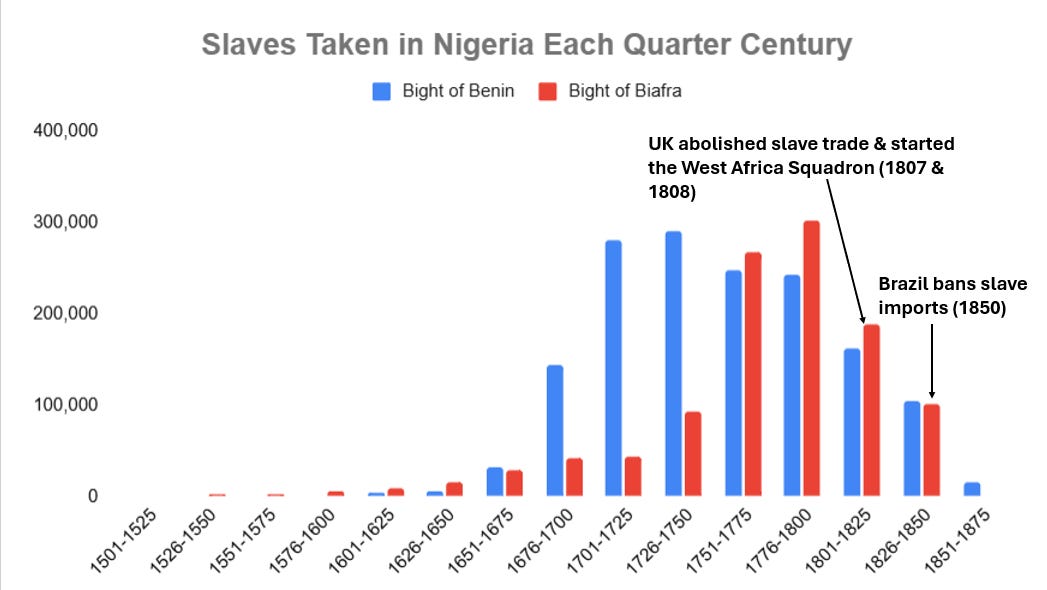

Initially, Denmark abolished the slave trade in 1792, followed by Britain in 1807. The following year in 1808, the Royal Navy’s West African Squadron intercepted, seized, and destroyed dozens of Cuban, Brazilian, and Portuguese slave ships. British sailors earned prize money for each rescued captive. Many were resettled in Sierra Leone, where they later served as interpreters and agents for Britain’s expansion.

But enforcement proved difficult. Between the 1820s and 1850s, Spanish, Portuguese, and Brazilian traffickers still transported roughly 200K from each coast in the Bights of Biafra and Benin. Only after 1850, when Brazil banned slave imports and British patrols tightened, did the Atlantic slave trade finally collapse. Brazil's 1888 abolition marked its definitive end.

The Palm Oil Boom

As the slave trade withered, new commodities emerged from West Africa's forests: palm oil and palm kernels.

Long a food staple, palm oil was an input for many British industries—lubricating machinery, lighting cities through candles, and producing soap. Palm kernels, extracted from the same fruit, were processed into margarine and cooking oils.

Liverpool firms like Horsfall, Harrison, and Hemingway expanded imports from 40 tons in the 1780s to over 20K tons annually by the 1850s, representing two-thirds of Britain's West African trade.

British manufacturers marketed palm oil products as “moral trade”, urging consumers to "buy candles and stop the slave trade." The message was compelling, but it masked a darker reality.

Geographic Winners & Losers

Not all African kingdoms could capitalize equally on this new trade. The Kingdom of Benin adapted quickly, pivoting from slave exports to palm oil production even before abolition. But geography worked against them. The Itsekiri (ee-chay-ree) Kingdom in Warri controlled the lower Benin River with their canoe fleets, choking Benin's access to European traders and diverting commerce to their own ports.

The real winners of the palm oil trade lay eastward. Bonny and Old Calabar, positioned at the mouth of the Bight of Biafra, became the dominant palm oil hubs—the “(palm) oil Rivers” that would give their name to Britain's first protectorate. These city-states possessed the perfect combination: river access to interior palm groves, established trading networks, and political systems flexible enough to manage the transition from human to vegetable exports.

The Labor Paradox

Palm oil was brutally labor-intensive: roughly 300 lb of fruit yielded just 36 lbs of oil after three to five days of work. Men climbed palms and harvested; women shouldered most of the processing, transport, and market sales.

Some palm oil farms came family plots and women's cooperatives, but most of it was driven by slave plantations run by secret societies like Ekpe in Calabar and Okonko in Igboland or African chiefs and merchants across Edo, Ijaw, & Yoruba lands. The irony cut deep—the commodity meant to replace the slave trade created new demands for enslaved labor.

European merchants would sell cooking utensils, salt, cloth, alcohol, arms, ammunition, textiles and cowries (on credit) to African middlemen merchants. The African middlemen would sell European goods to inland African suppliers in exchange for palm oil, palm kernels, shea and ivory. This was known as the “Trust System”.

West African Warlords & Merchants

Two figures embody how African elites adapted:

Kurumi of Ijaye: A former Oyo war chief who fled the collapsing Oyo Empire during Fulani jihads. He carved out a new fiefdom around 1829 in his new home Ijaye by enslaving or expelling locals. By the 1850s, he commanded 300 wives and 1000+ slaves, exchanging palm oil for guns to maintain power until he died in the Ijaye War of 1861.

Ja Ja of Bonny (born Jubo Jubogha, later called ‘Ja Ja’ by the British): He was an Igbo man enslaved through the Igbo trading network called ‘Aro’.

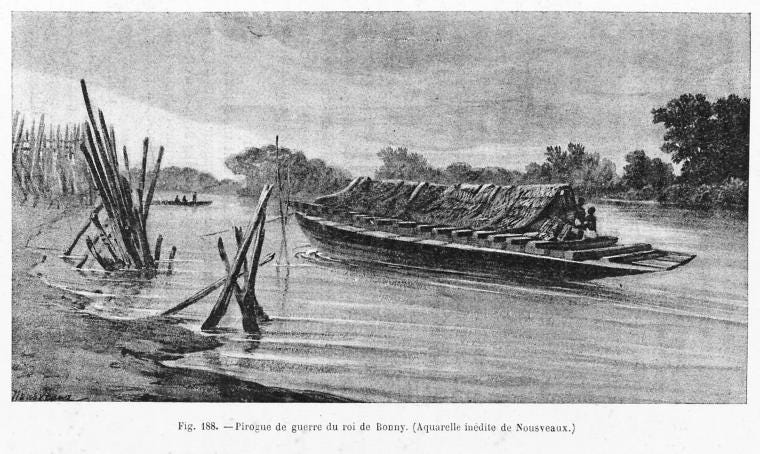

He was sold into Bonny's Anna Pepple House (a trading “House” is a mix of a compact, a canoe navy, and a trading & fishing corporation). Through organizing slave caravans into Igbo territory and managing European trade he rose to head the house in 1863 after his master died.

By the late 1860s, Jaja’s direct links to inland oil producers undercut rivals like Oko Jumbo of the Manilla Pepple House. In 1869, war broke out; Ja Ja withdrew and founded Opobo, a new settlement upriver commanding key palm oil routes.

From Opobo, JaJa eclipsed Bonny and drew European traders to his port.

British Exploration and the Medical Revolution

Britain’s deeper penetration inland began with exploration. The African Association and later the Royal Geographical Society sponsored expeditions that mixed three converging motives: scientific curiosity, Christian proselytizing zeal, and desire to bypass African middlemen and trade directly with African inland palm oil suppliers. Key explorers included:

Mungo Park (1st trek in 1794, 2nd in 1805): First European to trace the Niger inland, but drowned at Bussa rapids in his 2nd trek in 1805.

Hugh Clapperton (1822-27): Crossed the Sahara to meet Sultan Bello of Sokoto before dying from dysentery and malaria.

The Lander Brothers (1830s): Mapped the Niger river's full course, documenting cowrie shell currency and Oyo's political collapse

Yet diseases like malaria made the interior of West Africa the “white man’s grave.” Britain’s 1841 Niger Expedition sent three steamers upriver to sign treaties at Aboh and Lokoja, but malaria and yellow fever wiped out most of the crews. When the Church Mission Society (CMS) came to Abeokuta (Ah-beh-oh-koo-tah) (1846), most missionaries died within a year.

The Quinine Revolution

The turning point came in the 1850s with quinine. Indigenous South American peoples had long used the bark of the cinchona tree, and Europeans adopted it in small doses from the 1600s.

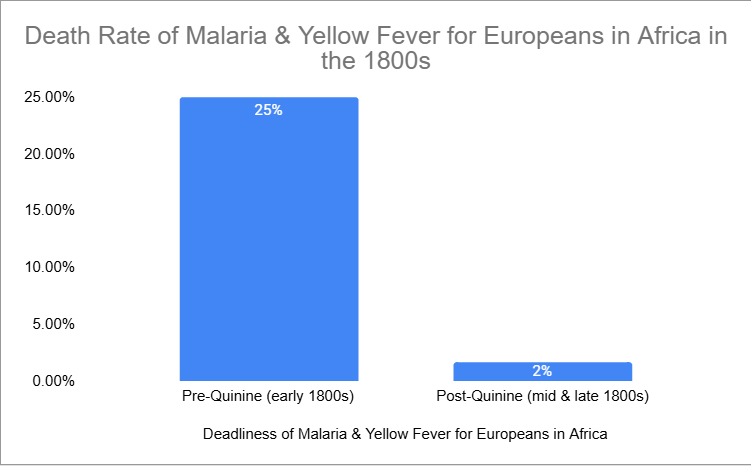

But in 1820, French chemists Pelletier and Caventou isolated quinine sulfate, a concentrated and portable form. By mid-century, British physicians began prescribing standardized doses for tropical service. Regular prophylactic use transformed survival rates: naval officers and missionaries who once lasted weeks could now endure months or years. Before quinine, about 25% of Europeans entering Africa’s interior died of malaria; by 1875, with widespread use of quinine, mortality had fallen to just 1.7%.

Quinine wasn’t only a lifesaver in West Africa but in India too—its bitter taste led the British to mix it with gin and tonic water, giving birth to the classic ‘gin and tonic.’

With quinine, Britain's ambitions shifted from coastal brokerage to inland conquest, bypassing middlemen. Merchants like Macgregor Laird sent steamers deep into the Niger, while German explorer Heinrich Barth documented Sokoto and Borno's economies with unprecedented detail.

The Christian Advance

Starting in the 1850s, the Church Missionary Society launched expeditions led by Reverend Samuel Ajayi Crowther—a Yoruba ex-slave who became the first African Anglican bishop in 1857—and explorer William Balfour Baikie.

They established mission stations at Lokoja and throughout Igboland. Crowther translated the Bible into Yoruba, standardized Yoruba into written form, and helped launch the first Yoruba newspaper in Abeokuta in 1859.

Missions spread to Bonny (Bun-nee) (1864), Nembe (1868), New Calabar (1874), and Okrika (1880), establishing schools and literacy programs. Other Protestant missions followed in Yorubaland and Catholic missions followed in Igboland in the 1860s. Notably, Igbo communities proved most receptive to Christianity, often fusing their old traditions with Christianity.

The Start of Control

Old Calabar: The First Experiment

Britain’s first real experiments with political intervention in what would become Nigeria started in Old Calabar in the Bight of Biafra. The Efik chiefs of Duke Town and Creek Town, wealthy middlemen in the palm oil trade, faced pressure from both missionaries and rival European powers.

In 1841–42, Efik rulers signed treaties with Britain to abolish selling slaves in the Atlantic slave trade and outlaw certain practices, including the killing of twins. (Twin births indicated maternal contact with evil spirits in this society). These treaties preserved their autonomy while strengthening ties with British merchants.

By 1849, the danger was French annexation. Chiefs along the coast had heard from sailors, interpreters, and merchants how France acted in other parts of West Africa—landing troops, planting forts, and turning “protection” into direct rule. To avoid the same fate, Efik leaders asked Britain for protection, gambling that London preferred trade over conquest.

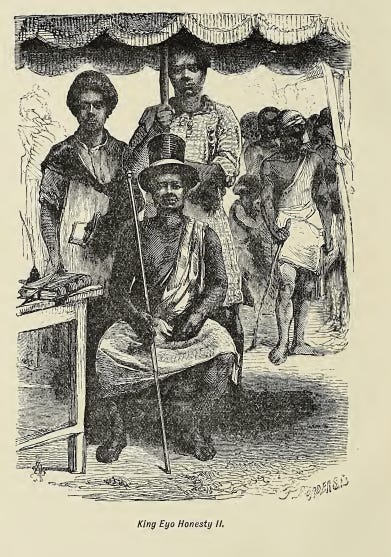

In 1849, British Prime Minister Palmerston appointed John Beecroft as Britain’s Consul for the Bights of Benin and Biafra. As consul, Beecroft’s role was to arbitrate disputes, pressure chiefs into anti-slavery treaties, and set up “courts of equity” for British merchants in the region. Based at Fernando Po (Bioko island in modern day Equatorial Guinea), Beecraft seized the opening in Old Calabar. He negotiated with King Eyo (eh-yoh) Honesty II of Creek Town to end ritual human sacrifice, and presided over the crowning of King Archibong (Ah-chi-bong) II in Duke Town.

Symbolic gifts—swords, waist belts, Danish guns, and brass rods—cemented the deal: Britain recognized a king and, in return, claimed the right to arbitrate succession and intervene in “inhuman practices.” These treaties did not annex Calabar, but they let Britain define legitimacy and morality in local politics. What began as anti-slavery diplomacy was already edging toward protectorate rule, setting the precedent for Lagos.

In Old Town in Old Calabar showcased what British “Humanitarian Intervention” looked like. In Old town, after a Chief died, he had a funeral, and the funeral involved “funeral sacrifices”. Among the Efik(eh-feek) of Old Town, a chief was not to enter the afterlife alone—his slaves and sometimes wives were killed to accompany him. Similar practices existed elsewhere, from Viking ship burials to India’s sati (widow burning).

To the British, funeral sacrifices were just barbaric human sacrifice, so they bombed Old Town and razed it to the ground. This was only the start of British intervention.

Britain’s influence in Lagos

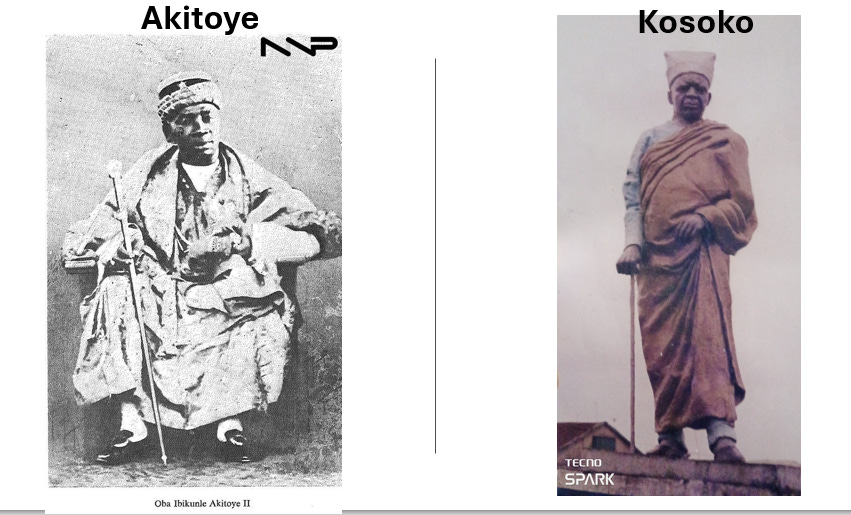

Lagos, West Africa’s busiest port and nominal vassal of Benin Kingdom, soon drew Beecroft’s attention. Despite being an economic hub, Lagos was politically unstable: internal family succession disputes, banishments, feuds with neighboring Badagry, and a constant struggle between its Oba (King) and chiefs. The breaking point came in 1845, when Prince Kosoko (Ko-soh-ko) overthrew his uncle Oba Akintoye (“Ah-kin-toh-yeh) & his followers, who fled to Badagry.

At Badagry, Akintoye met the British. Akintoye—a former slave trader himself—saw an opportunity for restoration through the British. Akintoye made a calculated bargain with Consul Beecroft: the British would restore him to the throne, and in exchange, he would ban slave exports and promote palm oil trade instead:

“my humble prayer to you is that you would take Lagos under your protection, that you would plant the English flag there and that you would re-establish me on my rightful throne at Lagos and protect me under my flag; and with your help I promise to enter into a treaty with England to abolish the slave trade at Lagos and to establish and carry on lawful trade, especially with the English merchants” — Akintoye

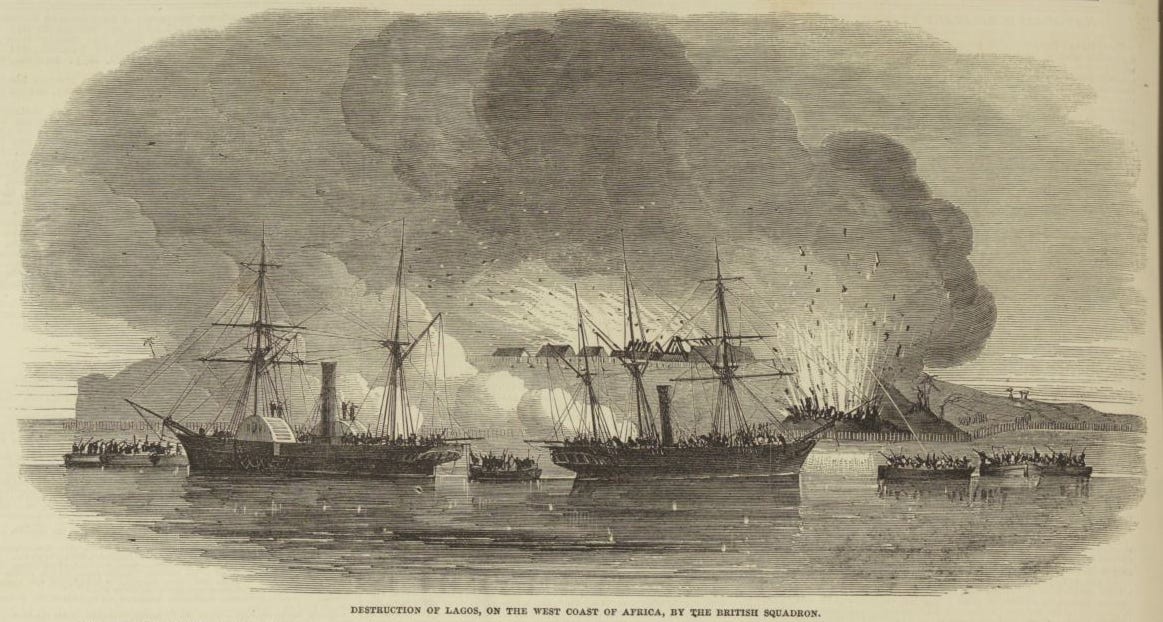

The Bombardment of Lagos

Beecroft attempted diplomatic resolution, but Kosoko rejected British demands and fired on British ships—an act Beecroft interpreted as a declaration of war. The Royal Navy bombarded Lagos and attacked Oba’s Kosoko’s palace in retaliation. By December 28, 1851, Kosoko and his chiefs fled Lagos for Epe, a town 60 km away from Lagos. Akintoye was brought ashore to reclaim his throne.

The Price of Restoration

With Akintoye restored as a British puppet, the real terms of his "rescue" became clear. The new treaty imposed restrictions on Lagos sovereignty:

"Most favored nation" (preferential) trading status for Britain

British consul authority over all trade disputes and commercial law

Akintoye felt like he lost sovereignty of Lagos. Meanwhile, Beecroft negotiated a similar treaty with Abeokuta chiefs in 1852, extending British influence inland.

The Puppet King System

Benjamin Campbell was appointed Consul in Lagos on July 21, 1853, wielding far more power than the nominal Oba. When Akintoye died, Campbell unilaterally installed Dosumu (Do-so-moo) (Akintoye's son) as the new Oba, completely ignoring Lagosian succession tradition where head chiefs mediated succession.

The chiefs would have preferred Kosoko’s return from exile in Epe(eh-peh), since he would bring back the slave trade in Lagos, which was the source of obtaining cowries, guns, and cloth for the chiefs. But Kosoko’s open support for the slave trade made him unacceptable to Britain. Dosumu, meanwhile, commanded little respect.

As Nigerian historian & British historian, Ajayi & Espie noted: “Upon Akintoye's death, the throne went to his son, Dosunmu, a weakling who was so fearful of his cousin Kosoko."

The Shadow Kingdom in Epe

Dosumu's illegitimate rule made many Lagosian chiefs view him as a British puppet. Meanwhile, Kosoko established himself in Epe, building up a rival base with ~400 warriors. His war canoes harassed Lagosian palm oil routes, his agents sold off Dosumu’s people into slavery, and his warriors raided Lagos itself. Without British troops, Kosoko would have taken over and the selling of slaves to Brazil would have continued.

To contain him, Campbell brokered the Treaty of Epe (1854): Kosoko renounced claims to Lagos in exchange for recognition of his rule in Epe, a territorial concession in Palma (a small port east of Lagos), and an annual allowance of 2K cowrie shells (their currency). The peace was fragile. Lagosians knew that Dosumu’s throne rested on British guns.

Anglo-French Competition

The delicate balance between puppet ruler and rival claimant proved unsustainable. After Campbell died in 1859, his successor Consul Brand warned the Foreign Office that French delegations were courting Dosumu. France annexed Algeria (1830), Libreville in Gabon(1849), and was consolidating Senegal in the 1850s. Lagos seemed next.

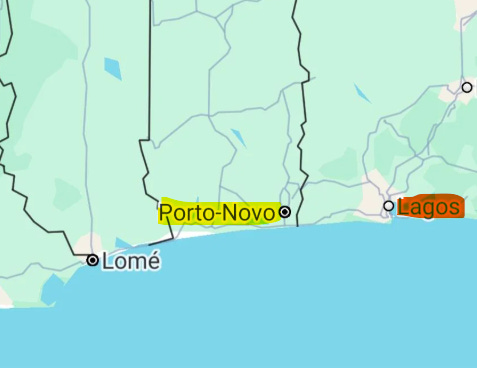

Brand served only a year before Consul Henry Foote took over, arguing that lasting influence required permanent British troops and inland consul stations. The breaking point came in 1861 when Porto Novo embargoed palm oil sales. Foote bombarded the port, forcing a free trade agreement with Porto Novo afterwards. But, that action made Foote conclude that similar clashes with Lagos were inevitable unless Britain annexed it.

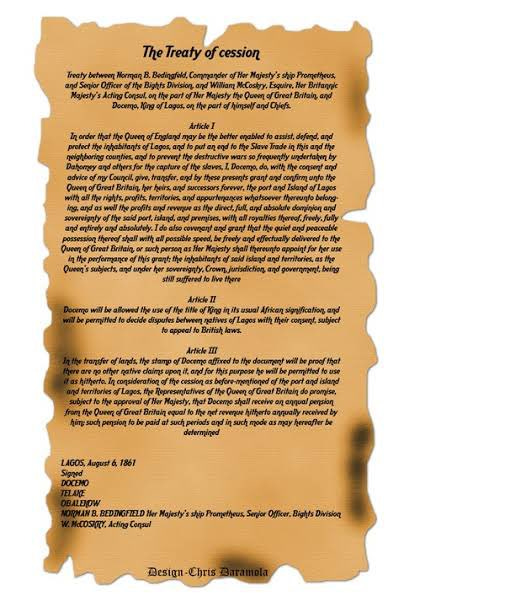

In August 1861, acting consul William McCoskry secured Dosumu's signature on the Lagos Treaty of Cession, officially transferring sovereignty to Britain in exchange for a pension of £1,030 annually. Dosumu signed reluctantly, fearing assassination by his own court.

British Lagos

Henry Stanhope Freeman was appointed by Britain as the first governor of Lagos. British interests in ending the slave trade and in palm oil & palm kernel trading were firmly prioritized. The merchant community reflected this dominance: 16 British firms dominated the port alongside 1 French, 2 Italian, 3 German, and 5 Brazilian companies.

The colony developed into a busy, cosmopolitan port with a diverse black elite composed of English speakers from Sierra Leone and emancipated slaves repatriated from Brazil and Cuba. These residents found employment in official positions, sat on the appointed Legislative Council, and thrived in business. Richard Blaize exemplified this success, building a small fortune through his import-export trading firm.

France struck back by annexing Porto Novo in 1863. To prevent territorial warfare, Britain and France signed the Anglo-French Convention of 1863, partitioning the region along the Yewa River and splitting the Yoruba-speaking communities between the two colonies.

Ironically, Parliament had expressed desire to withdraw from West Africa in 1865, viewing colonies as expensive liabilities. But the same logic driving modern American military presence abroad—"if we leave, someone else will fill the vacuum"—compelled Britain to expand rather than retreat. The fear that Germany or France would capitalize on any British withdrawal deterred disengagement. Lagos, once a battleground between rival Obas, had become the start of Britain's colonial foothold in Nigeria.

Conclusion & Ending Thoughts

The colonization of Lagos shows how empire often emerged not from a master plan but from a string of ad-hoc “solutions”—suppressing the slave trade, promoting palm oil, checking French rivals, propping up client rulers—each step making withdrawal harder until annexation seemed inevitable. Now magnify this across the entire globe, and that is the story of the British empire.

America followed a similar path after WWII. Moral claims about ending communism or spreading democracy, stability, and human rights justified interventions, military bases, and permanent commitments. The U.S. found that once it intervened, continued influence seemed more rational than leaving (usually condemned as “isolationism”).

The logic is consistent: Britain and America both intervened out of a moral/stability claim which necessarily led to consolidating influence. Britain saw itself as a moral crusader by smashing Portuguese slave ships, banning practices like twin killing, slavery, and funeral sacrifice in the coast of the Niger Delta, and increasing literacy among newly Christianized coastal West Africans — just as America later justified protecting South Vietnam from communist North Vietnam, conditioning aid to developing countries predicated on multiparty elections in the 1990s, and defending its presence in Afghanistan by pointing to women’s education. Influence has a dual logic: humanitarian work provided a rationale for creating long-term leverage and/or military presence.

Both U.K. & U.S. started by denying they wanted hegemony, but each crossed a threshold—Britain taking India from the East India Company in 1858, and America after WWII.

The question is, will China ever cross that threshold? For now, China seems cut from a different cloth —focused less on “global moral policing” and focused more on reuniting with Taiwan, claiming its waters in the South China Sea, and building global economic leverage to deter Western pressure. Beijing has resolved some of its numerous border disputes through negotiation rather than war, and even in places like Myanmar it avoids taking sides despite the conflict spilling across its border.

Next time, in part XIII, I’ll discuss how Britain colonized Old West African powers like Benin & Ibadan, finances of the Royal Niger Company, and how “merchant colonialism” gave way to government colonialism of Nigeria—just like in British India.

Sources

The Compatibility of the Slave and Palm oil Trades in the Bight of Biafra by David Northrup

UNESCO General History of Africa, VI: Africa in the 19th century until the 1880s by J.F.A. Ajayi

UNESCO General History of Africa, VII: Africa under Colonial Domination 1880-1935 by A. Adu Boahen

An Economic History of West Africa, 2nd edition, A.G. Hopkins

The End of the “White Man's Grave"? Nineteenth-Century Mortality in West Africa by Philip D. Curtin

I made a meme satirizing some of the moral dilemmas Britain faced https://imgflip.com/i/a6ptj6

Dude thank you so much for not making this one in that AI fake podcast format.