Beyond Victims and Villains: Understanding African Agency in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade

Part V of the Remastered Series of Nigeria (1560-1700s)

Introduction

Everyone has heard of the Transatlantic slave trade — but how much do you really know about it?

Did you know that Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, England, France, and even Denmark all competed for West African slaves?

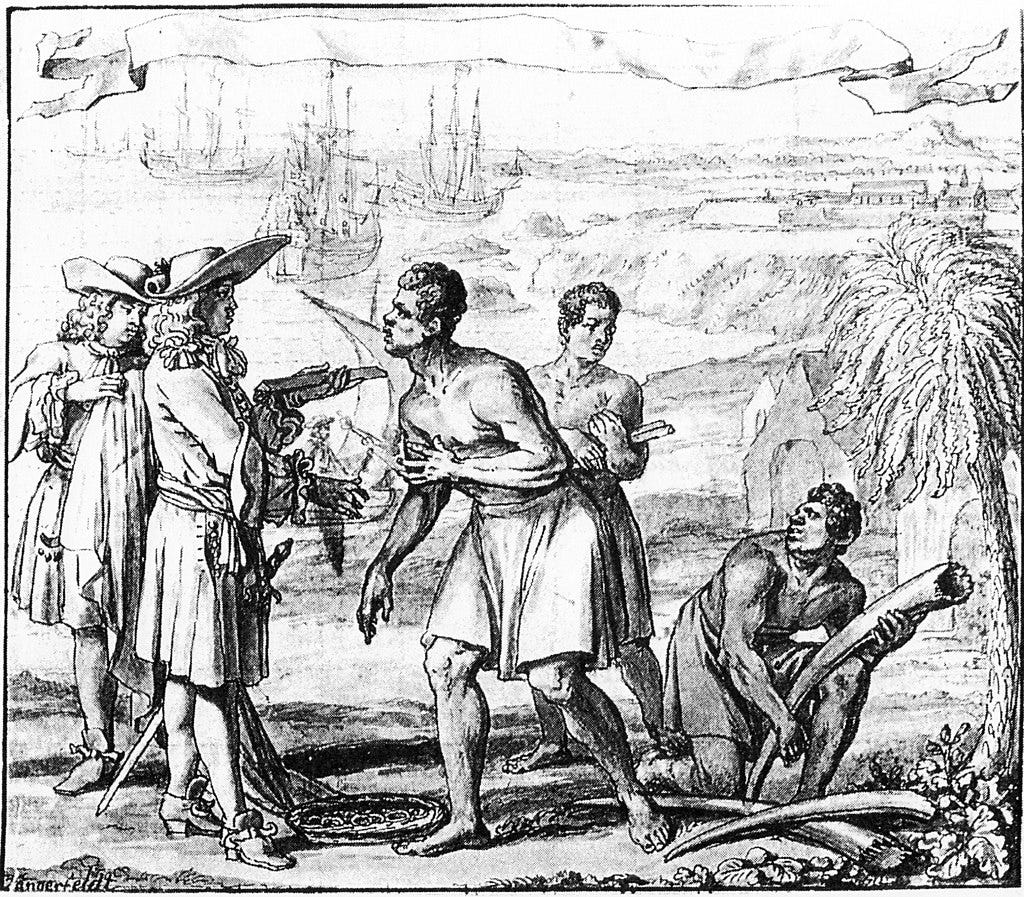

Did you know the trade would not have been logistically possible without African polities kidnapping and selling other Africans? For centuries, Europeans were unable to kidnap the Africans themselves at scale since they died from diseases in the African interior such as malaria, trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), dysentery, or yellow fever. Until the 1800s, when Europeans developed prophylactics for tropical diseases, Africa was nicknamed the “White Man’s Grave.”

Did you know that instead of direct capture, Europeans supplied cowrie shells and manillas to the African coastal polities as payment for selling slaves? During the slave trade, cowrie and manilla functioned like modern paper money. Essentially, European merchants inadvertently functioned as the central bank of West Africa from the 16th to 19th century.

This is the story of how the Trans-Atlantic slave trade transformed Pre-colonial Southern Nigeria's kingdoms — who profited, who suffered, and how entire societies restructured around selling human beings.

Our Story so far:

Part I: Recap of Modern Nigeria & Nigeria’s foundations (1000 BC - 1100AD)

Part II & Part III: Northern Nigeria’s Islamic states from 1100 to 1900 AD.

Part IV: Southern Nigeria before the European slave trade expanded, ending in 1560 AD when Yoruba Kingdoms like Ife and Oyo fell to Nupe cavalry raids.

Today's Focus

We'll explore Southern Nigeria during the slave trade's expansion, concentrating on a few kingdoms:

The Benin Kingdom — coastal Edo-speakers who controlled the sea routes

The Oyo Kingdom — inland Yoruba-speakers who dominated the hinterland

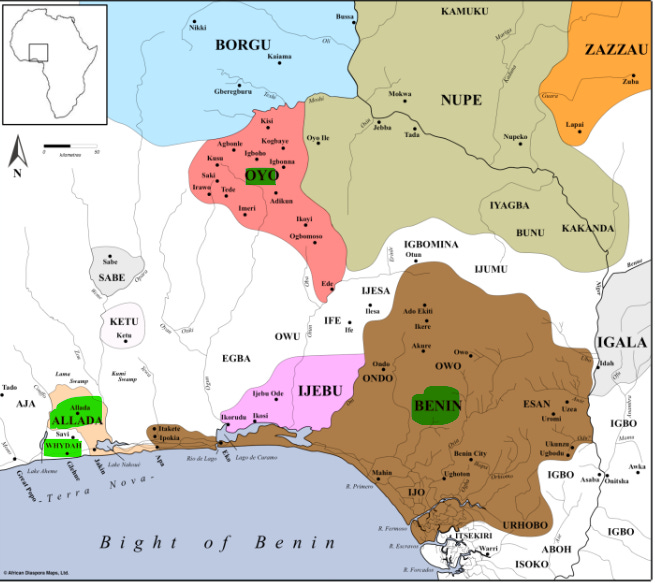

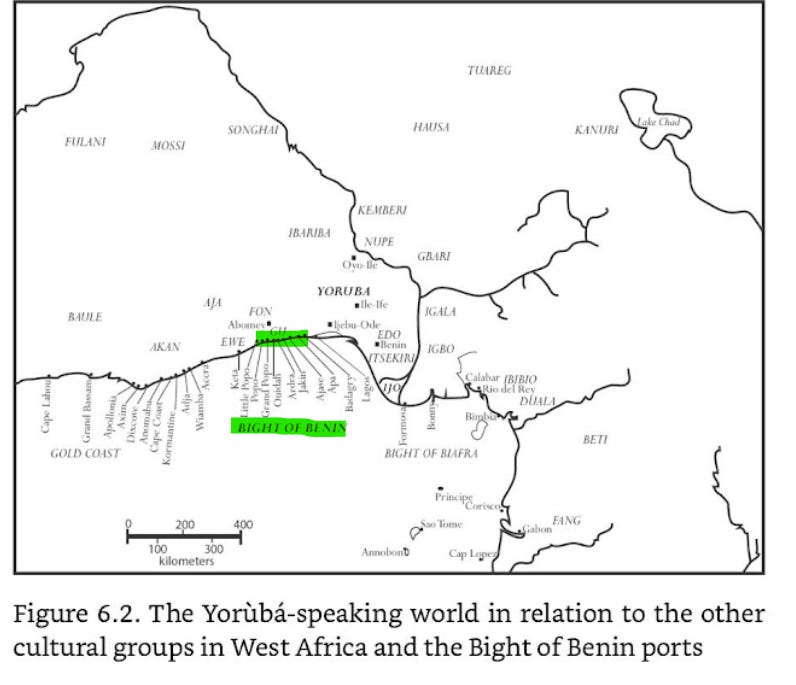

But they weren't alone. Along what Europeans called the "Slave Coast," Allada, Whydah, Grand & Little Popo — coastal kingdoms in modern-day Benin and Togo — became the slave trade's bustling marketplaces. These ports witnessed scenes that would haunt history: European ships anchored offshore while African merchants haggled over African human cargo on the beaches.

Together, these kingdoms' choices would reshape West Africa forever.

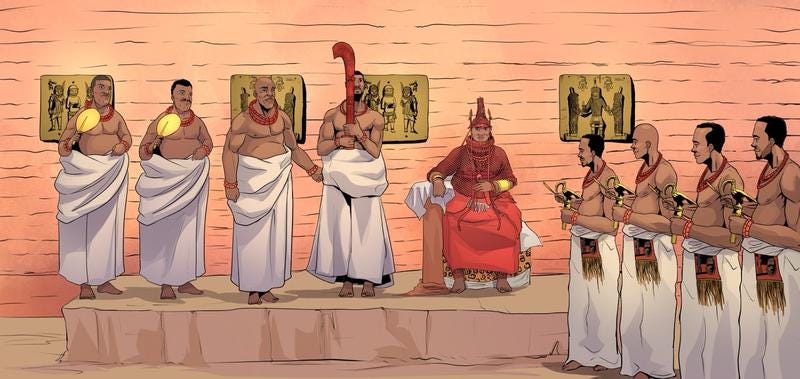

The Edo people of Benin: A Different Path than Selling Slaves

Benin & The Portuguese

As mentioned in the previous article, from the 1400s to mid 1500s, through trade with the Portuguese, some Benin political elites & merchants learned to write and speak in Portuguese.

While other West African kingdoms eagerly sold captives to European slave traders, Benin chose a different path. In the 1500s, the Edo kingdom banned the export of (male) slaves and stuck to it—even as its African competitors amassed luxury goods from human trafficking.

I wouldn’t really say this is because political elites of Benin had exceptional moral character. Benin's wealthy war chiefs, the Ezomo, owned plenty of slaves as farm workers and personal servants. They simply refused to export their valuable labor force. Instead, Benin sold other goods to Europeans — hunting elephants for ivory, cultivating pepper, weaving cloth, and extracting dyes—anything but selling male captives.

The strategy had costs. Portugal, frustrated by Benin's slave ban and repeated rejection of Christianity, abandoned the kingdom entirely in the mid-1500s. Portuguese traders flocked to more "cooperative" partners: the Kongo, coastal Yoruba (Ijebu-Ode), the Aja-speaking Popo states, and the Douala of modern-day Cameroon, who were relatively more welcoming to missionaries and unrestricted slave trading.

Benin & The English

But profits from Guinea pepper & ivory proved irresistible. Despite Portugal's departure, France and England rushed to fill the vacuum. In the 1550s, London merchants hired Portuguese captains to guide them to West Africa. Under Oba Orhogbua (1550–1578), the English merchants traded Indian and Dutch cloth, beads, cookware, mirrors, and tools in exchange for Guinea pepper and ivory, even taking pepper on credit in Benin City. All trade went through the Oba, who negotiated quantities personally.

But West Africa’s fevers were merciless. Malaria or yellow fever killed five crewmen a day; most of the English party died. Throughout the 1500s and 1600s, English merchants kept dying of malaria when they entered Benin.

Still, the profits from Guinea pepper outweighed the mounting dead bodies, and fleets kept sailing. The English started offering advice on how to avoid dying by disease in Benin:

It rarely worked. The death count was piling up so Queen Mary banned English voyages to “Guinea, Bynie, and the Mina” (modern-day coasts of Ghana, Togo, Benin, and Southern Nigeria) in 1556. But, many London investors ignored the ban.

Then came the Dutch, and everything changed.

Benin & The Dutch

By 1593, Dutch merchants learned from the failures of the British & French and managed to trade with West Africa in larger quantities while avoiding mounting corpses. They asked Benin to prepare pepper shipments in advance, minimizing deadly time ashore and reducing crew deaths. Their superior ships, navigation, and smaller crews slashed costs while their European competitors' men died by the dozens.

Most importantly, the Dutch refused to play by African rules. While some English and French merchants still sailed inland to negotiate face-to-face with the Oba in Benin City—a death sentence for Europeans—the Dutch stayed at the coast. They traded through Edo middlemen at riverside posts like Ughoton and Arbo. Then, the Dutch expanded beyond Benin entirely, cutting deals directly with coastal Yoruba, Ijo, and Itsekiri traders eager to sell war captives. Trade moved from the Oba's palace to the waterside—faster, cheaper, and safer.

This wasn't just smart business—it was also about empire building. In 1621, Amsterdam merchants created the Dutch West India Company (WIC) with one mission: destroy Portuguese dominance of the Atlantic.

For two decades, they nearly succeeded. The Dutch seized Brazil's Pernambuco (1630), captured the Gold Coast's São Jorge da Mina (1637), and took Portugal’s Luanda in Angola & Sao Tome (1641). They forced Portuguese ships to pay 10% tariffs and restricted Portugal to trading only Bahian tobacco in West Africa. For over a decade, Dutch merchants succeeded in the West Africa trade while the English “Company of Adventurers (1631)” failed to turn a profit in West Africa.

But Dutch momentum faltered after 1645. Profits from the Guinea trade slumped; Portugal counterattacked, retaking São Tomé and Luanda in 1648 and driving the Dutch out of Brazil by 1654. The WIC, bleeding money, and massively overleveraged with debt, collapsed financially and was dissolved in 1674. The WIC wasn’t nearly as successful or profitable as the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in Indonesia, which lasted until 1799.

Benin’s Adaption

As European powers shifted, so did Benin's exports. When the Dutch East India Company flooded Europe with Indonesian pepper, Guinea pepper demand plummeted. Benin pivoted to ivory and Edo cloth—the cloth became especially valuable, traded by Dutch and English merchants to the Gold Coast for gold and to Kongo for slaves.

Benin’s trade dwindling

While Benin clung to its cloth, pepper, and ivory trade, neighboring kingdoms made a different calculation. The Aja-speaking ports of Allada and Whydah (both are in modern-day Benin Republic, which is NOT the same as the Benin Kingdom) committed fully to human trafficking—and it enriched their courts with European clothes, firearms, and prestige items.

By the 1630s, the transformation was obvious. Allada and Whydah became prime destinations for European merchants, taking commerce flow away from Benin’s coastal outposts in Ughoton, Lagos, and Mahin. Between 1640–1650, Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, English, French, and Danish all descended on these outposts, buying human cargo for North and South American plantations where captives would be worked to death producing cotton, sugar, and tobacco.

The Benin Civil War

Just as the slave trade exploded, Benin imploded. Between 1689 and 1721, the kingdom was engulfed in civil war—a savage conflict over royal succession that reduced the once-mighty capital to "a mere village."

Historians disagree on where to place the blame. I’ll synthesize all three writers I’ve read on this.

A.F.C Ryder (who relies on European archives) & Philip Igbafe (who blends Edo oral tradition & European archives) trace the conflict to succession disputes after Oba (King) Oreoghene died. With dozens of royal wives and no birth records — one of the many issues of an oral-based society — multiple princes claimed to be the “first-born son” in order to seize the throne. Palace chiefs, war leaders(Ezomo), and urban nobles (Iyase) each backed different candidates, turning politics into warfare.

Oba Ewuakpe was eventually installed, but historian Jacob Egharevba, relying on Edo oral tradition, emphasizes that Ewuakpe’s own misrule drove him to exile and exacerbated the crisis in Benin.

Rival factions installed rulers "under protest." By war's end, royal authority had shattered. Portuguese merchants were courted to mediate the conflict; Dutch merchants sold guns that only prolonged the carnage.

The wars dragged on for decades, hollowing out royal power. Benin lost control of much of its surrounding territory. Stability only returned under Oba Akenzua I (1713–1735), who reunited the kingdom and reasserted central authority.

Bringing Back Slavery

When Oba Akenzua I came to power in 1713, the throne was fragile. Years of civil war had splintered royal authority and left him dependent on uneasy chiefs and war leaders. To stabilize his rule, he needed guns and powder, which only the Dutch were willing to supply. The Dutch merchants pressed hard, demanding:

Akenzua resisted, preserving the trust system and refusing to grant any monopoly. But he made one crucial concession: lifting Benin’s long-standing embargo on exporting male slaves.

The decision was driven not just by internal weakness but by fear of encirclement. To the north, Oyo had built a slave raiding, cavalry empire; to the west, Dahomey conquered the slave export Kingdoms of Whydah & Allada. Both threatened to reduce Benin to a client state. For Akenzua, reviving the slave trade was less a policy choice than a survival strategy — a way to arm the monarchy, hold fractious chiefs in line, and keep his kingdom independent from the Fon-ethnic Dahomey or Yoruba-ethnic Oyo.

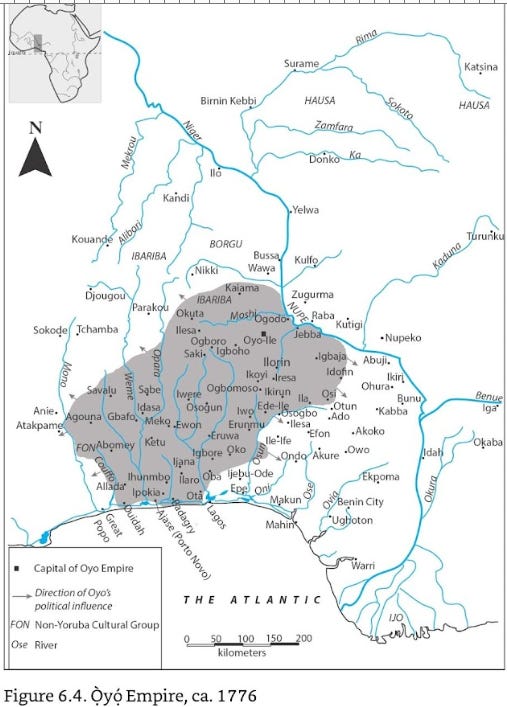

The Yoruba of the Oyo Empire: From Humiliation to Slave Trade Hegemony

The Rebirth of the Oyo

After Nupe cavalry crushed Oyo in the mid-1500s, the defeated Alafins (Yoruba kings) fled to Borgu and licked their wounds. But Yoruba Kings learned a crucial lesson: you can only beat horse raiders by becoming horse raiders.

The Cavalry Revenge

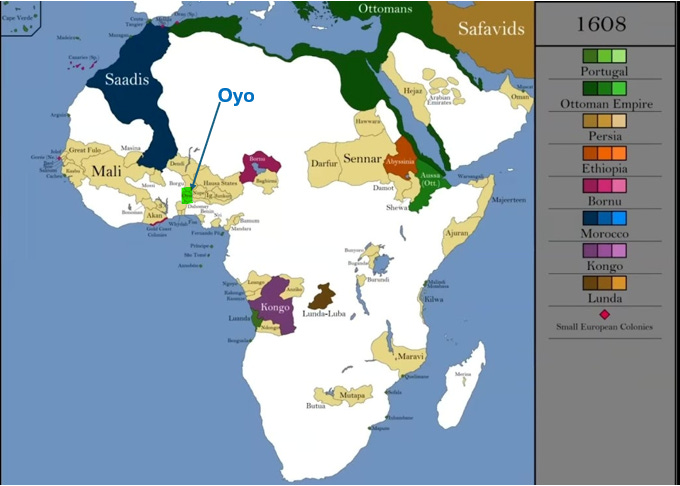

By 1608, Oyo had adopted the same mounted warfare that destroyed them. Under Alafins Abipa and Obalokun, Oyo's revenge was swift and brutal against the Nupe. They swept east, seizing Upper Osun, Igbomina, and Ekiti from their former tormentors. When Obalokun pushed south, only the tsetse fly stopped him—his horses couldn't survive the blood-sucking insects of the forest belt. To the west, Oyo expanded its reach after Morocco’s destruction of the Songhai Empire, securing new trade routes.

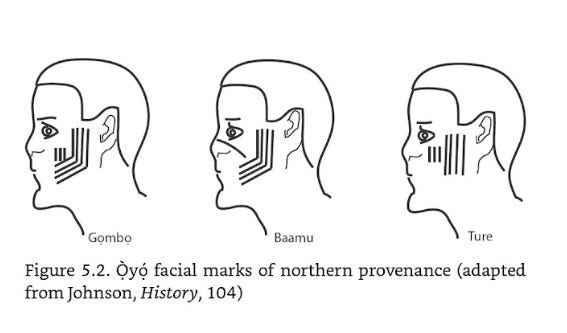

Oyo had become something new: a multi-ethnic empire binding Yoruba, Nupe, Songhai, and Mossi peoples under one political identity. Power was shared between the Aláàfin (king) and the Ọ̀yọ́mèsì, the council of seven noble lords. Slaves provided the bureaucratic and military backbone of society.

The Types of Slavery/Bondage in Oyo

These were the forms of domestic slavery/bondage/servitude (eru) in the Oyo Empire.

War Captives: Taken in battle, sold to other Africans or kept as farm laborers, miners, or cloth workers.

Iwofa (Pawnage): A child or relative was pledged to a creditor until debts were repaid.

Palace slaves: The Oyo political elite would sometimes castrate their slave into a eunuch and they would serve as a tax collector, judge, or guard. Why were they castrated? Eunuchs lack lineage and thus lacked incentive to be greedy enough to build rival power bases.

Concubinage: Female captives were given to chiefs or the Alaafin; some gained influence if they bore children.

Ritual slaves: Certain slaves were sacrificed to ancestors or deities.

Oyo Shifting Trade South

Initially, Oyo supplied the Trans-Saharan trade: raiding neighbors like the Nupe & Borgu, then selling captives to the Northern Sahelian states for horses, repeat. But from the 17th century, Oyo’s sharp-eyed merchants noticed something intriguing about southern trade. The southern coastal markets offered European goods that the northern Sahel couldn't match.

What were those goods? Besides firearms and glass beads (which the Sahel provided too in limited quantities), the Southern Africans provided Oyo Maldivian cowrie shells.

What’s so special about Maldivian cowrie?

In the 16th century, Portugal reached the Maldives during their exploration of the Indian Ocean. Maldivian women supplied the shells on Portuguese boats, and Portugal brought cowries to West Africa.

In the Bight of Benin in West Africa, many African merchants were enamored with Maldivian cowrie shells when trading with Europeans. African merchants bought them up and cowries functioned as money. Before cowries, Oyo’s economy relied on clumsy barter — every deal required haggling, and goods like food or livestock spoiled or couldn’t be divided easily.

Cowrie shells had all the properties of money: widely accepted, portable, and hard to counterfeit. As a result, the Maldivian cowrie shell was a medium of exchange and a unit of account. Tolls, levies, fines, and tribute were all “priced” in cowries inside Oyo’s domain.

The Oyo empire even developed banking thanks to the slaves-for-cowries trade—rotating savings clubs called Èsúsú and community accounts called Àjọ.

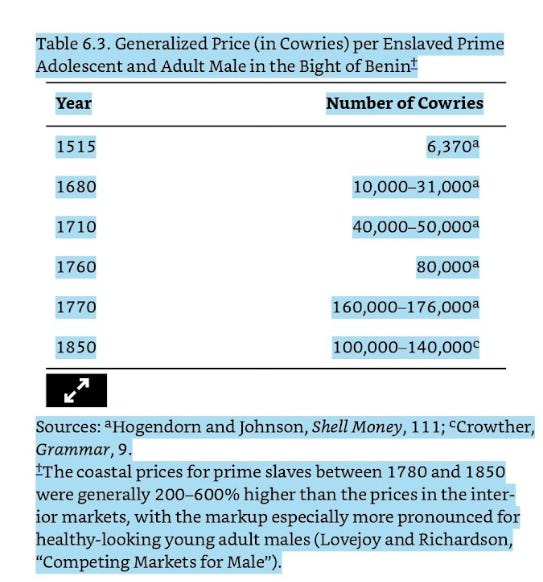

Cowrie shells were the main object received in return for selling slaves in the Bight of Benin (The Coast of Southern West Nigeria). 44% of all slaves & African goods in the Bight of Benin were exchanged for cowrie shells. Take a look at the chart below:

The Middleman's Game

But here's the catch: Oyo seldom dealt directly with Europeans. Instead, Oyo, along with other inland Yoruba states like Ijesha, Owu, & Ondo, operated as middlemen in an elaborate supply chain.

For non-slave goods dyestuff, iron, cotton, and kola nuts, they traded with the Edo-speaking Kingdom of Benin (which had banned male slave exports until the 1700s). For human cargo, they sold to the Aja-speaking coastal kingdoms of Whydah (Ouidah or Hueda) on the Western edge of the Bight of Benin or of Allada (Ardra), which was further east and dominated the outposts of Offra and Jakin.

Both coastal powers (Whydah & Allada) ran tight monopolies. Whydah banned all direct trade—captives could only be sold through royal agents, ensuring that the king controlled both supply and price. Allada allowed free trade but reserved firearms and cowrie purchases for the king. Either way, they controlled the terms between Oyo and European buyers.

European merchants paid coastal African Kingdoms with cowrie shells, textiles, manillas, and other goods, which the coastal Kingdoms then used to buy more captives from inland suppliers. The cycle repeated for centuries.

The results were bloody for weaker polities. Raids escalated as Yoruba states — Oyo, Ijesa, Ondo — attacked weaker Yoruba states like Ife and smaller communities, seizing captives to sell to coastal powers like Allada and Whydah. Yoruba oral traditions in towns such as Ojo, Awo, and Ara still recall the reign of Uyìarère of Ijesa, where brigands prowled the countryside. Men, women, and children were kidnapped, driving farmers from their fields and women from the markets. Other coastal states got in the game too like Grand & Little Popo (both in modern-day Togo).

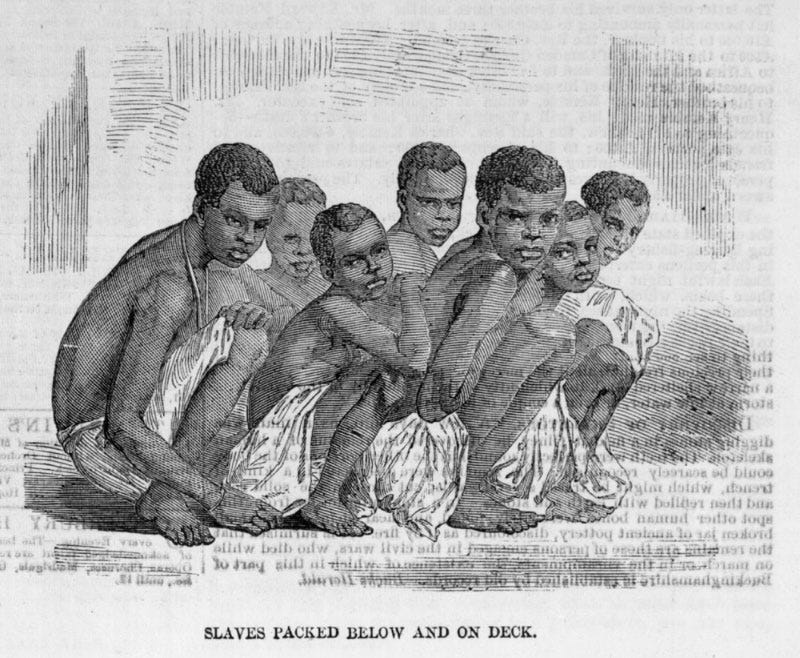

The numbers tell the story.

From 1625 to 1650, about 5K people were taken from the Bight of Benin—roughly 200 slaves each year.

Between 1651 and 1675, over 31K were enslaved, averaging 1.24K per year.

From 1676 to 1700, the total had soared to 143K, or nearly 5.7K captives every year—an astonishing escalation in human misery. See chart below:

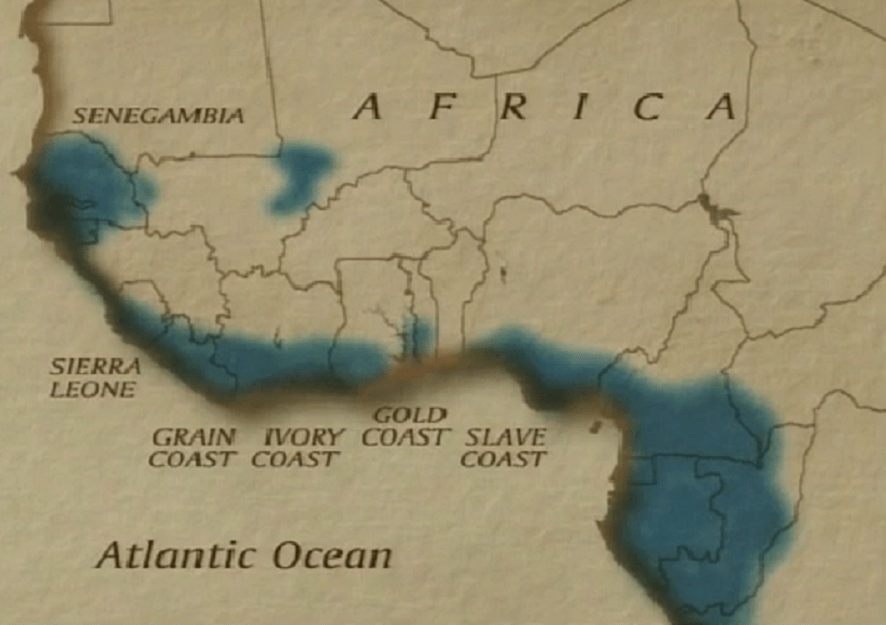

By the 17th century, Europeans labeled different stretches of West Africa after their chief exports — the shores of modern-day Liberia and eastern Sierra Leone as the “Grain (Pepper) Coast,” Côte d’Ivoire is French for “Ivory Coast,” the southern coast of modern-day Ghana as the “Gold Coast,” and the Bight of Benin in present-day Benin and Western Nigeria as "Slave Coast." See map below:

Oyo’s Golden Age

In the 1600s, Oyo vassalized Ijesa and Owu, demanding tribute from them in the form of slaves, cowries, and kola nuts. These conquests provided a steady stream of resources and captives, while cementing Oyo’s dominance in the Yoruba interior.

By the reign of Aláàfin Ọbalókun in the mid-1600s, Oyo had become the largest mainland supplier to the Slave Coast. Between 1650 and 1750, most captives Oyo marched to the coast came from three sources, in ascending order of importance:

Tribute from vassals

War-raids

Purchases from other African polities like Nupe, Hausa, and others

In addition, the 17th century's Sahelian megadrought became Oyo's windfall. Across the savanna, famine and resource wars devastated Hausa city-states, Nupe, and Kanem-Bornu. Agricultural collapse and endless warfare produced captives in unprecedented numbers that I discussed in part III. More wars means more raids, and more raids means more slaves to purchase for the benefit of Oyo.

Oyo exploited the turmoil with a two-way trading system:

Northward: Oyo sold captives to Hausaland, Nupe, and Bornu in exchange for horses.

Southward: Oyo horse-mounted warriors raided villages, seizing more captives to sell to Whydah and Allada,

Among the Yoruba states, only Oyo had the military reach, transport network, and political organization to deliver captives to the coast in the vast numbers European merchants now expected.

Conclusion

There’s four conclusive points I want to make: about people’s mental model of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, the insane economic imbalance of this trade, the pricing of human beings in cowrie shells, and the potential parallel with the modern Middle East.

Beyond the Simple Story

In this section, I asked: Who benefited from the trans-Atlantic slave trade? While Europeans were the obvious beneficiaries, certain African polities also profited, particularly coastal brokers like Allada, Grand Popo, and Whydah and the powerful inland empire of Oyo.

But here's what strikes me: how differently people imagine this trade. Many Americans picture Europeans kidnapping Africans directly, not realizing tropical diseases made inland raids almost impossible for Europeans. Others understand that Africans captured other Africans, but miss the crucial reality—this was a sophisticated supply chain.

Inland states like Oyo raided weaker groups and marched captives to the coast, where coastal African brokers exchanged them with Europeans for goods like cloth, rum, firearms, and, most importantly, cowrie shells.

The Great Economic Imbalance

The imbalance of this exchange is striking. European merchants converted enslaved African labor into immensely profitable plantation economies that produced sugar, cotton, and tobacco for global markets. In contrast, African states in the Bight of Benin traded human beings primarily for cowrie shells for currency and luxury Indian clothes for prestige. In economic terms, Europe converted slave labor into productive capacity, while African polities in the Bight of Benin too often converted it into consumption, currency, or symbolic wealth.

Pricing humans in Cowrie Shells

Worse still, by trading people for cowrie shells, African states effectively fueled inflation. Cowries expanded the money supply without expanding production. In 1515, a male slave in the Bight of Benin was worth around 6,000 cowrie shells. By the 1770s, that same slave cost nearly 175,000 cowries — a staggering rise that reflects both inflation and the intensifying demand for human labor. See chart of the cowrie price of a human below:

That’s not the whole story, of course. In Oyo, cowries also spurred financial innovation. Systems like esusu and ajo — rotating savings and credit associations — used cowries to pool and circulate capital in new ways. Even in this bleak trade, there were legacies of development in finance.

The Parallel with the Modern Middle East

But overall, this trade was a dead-end. Kingdoms like Whydah and Allada essentially traded away people for perishable consumption and money tokens. The parallel today might be Gulf states, who sell oil and gas in exchange for imports like cars, airplanes, and computer chips. Look at Italy’s trade with Saudi Arabia below:

The difference is that Gulf states understand the risk: if they fail to diversify, they risk decline, especially if renewables kill oil & gas demand. You can read more about my parallel between African monarchies and Gulf States here. Whydah and Allada never adapted, and they were conquered by the African state Dahomey in the early 1700s.

Next time, we’ll continue our discussion of the slave trade in Southern Nigeria by discussing the Dahomey-Oyo wars, the Movie Woman King, the obscene expansion of slavery in the 1700s, the Oyo civil war, and more in part VI.

Fantastic question. The answer is geography.

Ghana has a longer, more accessible coastline with natural harbors, while southern Nigeria is swampy, lagoon-filled, and harder to navigate. The Niger Delta was among the deadliest environments for Europeans.

Ghana’s coast was still malarial, but less lethal. This allowed Europeans to establish forts at places like Cape Coast and Elmina Castle. Though Europeans still died, these semi-permanent bases gave rise to small Euro-African (‘mulatto’) communities. They were never more than 1K to 2K at best.

Very interesting article. I would add that slave labor in the Americas was not as productive as it appears. Most of it was used to harvest consumption products like sugar, tobacco, and rum. Both the Europeans and African middlemen were harvesting humans for pure (and unhealthy) consumption.